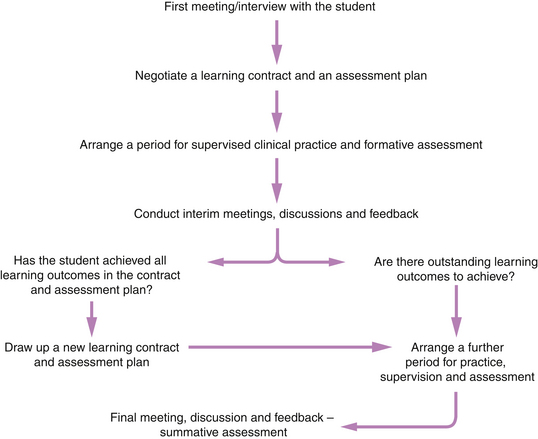

Chapter 6 It is discussed in Chapter 2 that assessors of students on health care courses have both professional responsibility and accountability to ensure that students they assess achieve safe and competent standards of clinical practice. These onerous tasks of assessing and conferring safety and competence are based on inferences made on a sample of the student’s performance. Such inferences are subject to error (Gonczi et al 1993, Rowntree 1987). Procedures need to be in place to ensure that the kind and amount of assessment evidence gathered are sufficient to make a safe inference and that the assessment is managed to ensure reasonable reliability to accompany greater validity. In other words, a carefully planned and managed assessment strategy is required so that the goal of professional education, which is to achieve fitness for purpose and practice, is fulfilled through the assessment processes. It would perhaps be a truism to say that students do not just achieve this ‘fitness’; rather, their learning requires facilitation as they work alongside practitioners during clinical placements. This implies that assessment has another key function besides that of obtaining evidence of competence: having a constructive focus where the aim is to help rather than sentence the individual (Gipps 1994). An important message from Crooks (1988) is that assessment appears to be one of the most potent forces influencing education, and it can have positive as well as negative effects. It is therefore necessary to plan and manage clinical assessment so that the powerful effects of assessment can be harnessed and directed positively onto learning about clinical practice. This section starts with an activity (Activity 6.1). The assumption made here is that not all of our experiences of being assessed are positive ones! You may have thought that the assessment was unfair because: • you were not given sufficient learning opportunities to develop and prove yourself • you were unaware of incorrect practices • your opinions of your progress were not considered • your assessor did not know you well enough to make the assessment decision Nicklin & Kenworthy (1995) and Rowntree (1987) believe that assessments give students opportunities to demonstrate the learning that has taken place. Assessments should thus have a constructive focus (Gipps 1994) whereby students are given the support, supervision and opportunities to demonstrate learning. Glaser (1990:480) emphasizes the importance of placing assessment in the service of learning, saying that assessments should: In health care, practical assessments of a student’s learning are context bound. Each patient or client cared for has different health care needs, which means that the student has to learn different aspects of care and different ways of responding constantly. An ‘accurate estimate’ of total learning can be made fairly only over a period of time, after a student has had continuous supervision and sufficient learning opportunities to provide the range of clinical experiences required to develop competence. In the UK, the impetus for the use of continuous assessment of theory and practice in nursing and midwifery education can be directly attributed to the perceived injustices of the final ‘one-off’ assessment, where factors such as anxiety and ill health may adversely affect the competence demonstrated on the day of the assessment. The result may not be representative of the overall abilities demonstrated by the student. Within early guidelines for continuous assessment, the English National Board for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting stated (ENB 1986) that: In later (1997) guidelines for continuous assessment the ENB stated: The position of the ENB in 1986 and 1997 on continuous assessment calls then for the use of formative and summative assessments, with the formative assessments feeding into, and informing, the summative assessment. The use of the continuous assessment of practice requires assessments to take place continually with periodic discussion, feedback, educational counselling and documentation throughout the student’s placement. Good continuous assessment demands substantial time and effort. This allows students’ performances to be monitored continuously during their day-to-day activities in clinical practice. Student efforts have to be steady and regular throughout (Rowntree 1987). Over the duration of the programme then, ‘a series of progressively updated measurements of a student’s achievement and progress’ are formally maintained in the student’s portfolio/ongoing record of achievement (NMC 2010, 2009, ENB 1996). Such measurements are made against given learning outcomes. The reference by the ENB in 1986 that ‘assessment should be a cumulative process’ means that every effort made by the student is assessed, and these series of assessments obtained through the continuous assessment process contribute to the summative assessment (see below); a final ‘end-of-the placement’ assessment is generally dispensed with (Rowntree 1987). The use of continuous assessment allows the quality and quantity of information about the student to be increased. In the case of pre-registration nursing and midwifery education, the requirement for students to spend a minimum of 40% of their time with their practice educators (NMC 2008) will facilitate the collection of a more comprehensive range of assessment evidence. The more we know about a student’s abilities the more likely it is that our assessment will be accurate. Continuous assessment of clinical practice has the following advantages: • Practitioners who are responsible for student learning can assess progress as it takes place. • The context-bound nature of practical assessments is reduced as the learner is assessed over the varied circumstances of different patients/clients cared for. • The learner receives continual and accurate feedback on performance and can identify areas where improvement is required. The practice educator’s personal knowledge of the learner and understanding of the context of the performance are significant advantages in providing valid feedback. • Areas for development and improvement can be planned jointly by the practice educator and the student. • The student is likely to feel supported and encouraged, as any learning and achievement will be seen as contributing to the summative assessment. Rowntree (1987) reports that students in higher education who have experienced continuous assessment believe it to be less stressful than the ‘all-or-nothing’ final assessment. However, White et al (1994) found that student nurses in their study felt continuous assessment during clinical practice to be stressful, saying that they were under scrutiny at all times and consequently had to exhibit best behaviours always. And is that such an onerous requirement, remembering that the behaviours of health care professionals towards their patients and clients and colleagues should be of an acceptable standard at all times? Both formative and summative assessments influence learning (Boud 2000). Summative assessment provides an ‘authoritative statement of … what counts … and directs students attention to those matters’ (Boud 2000:155). It tells students what to learn. The influence of formative assessment is no less profound. It provides the fine-tuning mechanism for what is learnt and how it is learnt. It should guide students in how to learn what they need to learn. It should also tell them the progress they are making. Formative assessment is founded on the principle of maximizing learning; assessment information about the student’s knowledge, understanding and skills are used to feed back into the teaching/learning process (Gipps 1994). In clinical practice, formative assessment refers to assessment taking place during learning activities and throughout the placement. It is conducted while the event to be assessed is occurring and focuses on identifying student learning and progress (Reilly & Oermann 1990). It focuses on parts of learning. The practice educator determines whether to re-explain, arrange further practice or move to the next stage. The assertion is that formative assessment can, and will, aid learning (Torrance & Pryor 1998). For this to take place, it is crucial that formative assessment becomes a process whereby both ‘feedback’ and ‘feedforward’ occur. Within this, practice educator–learner interaction becomes an important part of the process: it goes beyond the communication of assessment results, judgements of progress and provision of additional instructions. The practice educator and learner collaborate actively to produce a best performance (Torrance & Pryor 1998). An important role for the practice educator is to assist the learner in comprehending and engaging with new ideas and problems. The process of assessment itself is seen as having an impact on the learner as well as on the result of the assessment. Engage students in self-assessment. It is important to allow students to assess their own learning. Facilitate, and allow students to vocalize their perceptions of their achievements, ability and level of competency so that learning can start from, and build on, what the student already knows and can already do. From educational psychology, Ausubel (1968:163) stated strongly that: Some educationalists believe that assessment is truly formative only if it involves the student directly (Sadler 1989, Torrance & Pryor 1998). Self-assessment helps students feel that they own the learning and can thus control the way they meet their learning needs (Stoker 1994). It is linked with motivation, monitoring one’s own learning and becoming an independent learner (Gipps 1994). This is reinforced by Rowntree (1987:65) who says that a ‘pupil does not really know what he [sic] has learned until he has organized it and explained it to someone else’. Self-assessment facilitates this process. Additionally, Chambers (1998) says that self-assessment is an efficient and effective learning tool in that students are required to identify their own strengths and weaknesses. Students may need to be facilitated to be realistic so that they do not over- or underestimate their ability and capabilities. Students have an important role to play in planning their own learning and assessment. If they are to become competent assessors of their own work, they need sustained experience in ways of questioning and improving the quality of their work, and supported experience in assessing their work. The ability to self-assess one’s competence and achievements accurately is not a natural gift, but a skill that can be learned and improved upon with practice (Mattheos et al 2004). Feedback is crucial in helping students develop accurate self-assessment skills. Sadler (1989) argues that if students are to be able to compare actual performance with a standard, and subsequently act to close that gap, they must possess some of the same evaluative skills as their assessor. Writers such as Yorke (2003) and Boud (2000) stated that assessors should focus on the quality of feedback given, which in turn will enable students to develop and strengthen their skills of self-assessment. There is a discussion below of how to manage feedback constructively. Students are often well placed to assess their own learning and to regulate their own work appropriately. They will thus be able to indicate the amount and nature of clinical experiences they have had and recognize what clinical experiences they need in order to achieve competence. Falchikov & Boud (1989:395) highlight the need for students to take more responsibility for their own learning: ‘life-long learning requires that individuals be able not only to work independently, but also to assess their own performance and progress’. One key aim of self-assessment should be to shift the student’s focus from ‘how good am I?’ to ‘how can I get better?’ (Mattheos et al 2004:385). This ability will help students develop awareness of their own standards of practice. It is therefore important to handle student self-assessment well and in a positive, constructive way rather than in a negative norm-referenced way, as this can be demotivating (Gipps 1994). By listening to students the practice educator will learn what students consider their own learning needs to be. What is known about how adults learn says that adults learn best when they can see the relevance of what they are learning (Jarvis & Gibson 1997, Knowles 1990). The practice educator should therefore respond to the student’s expressed learning needs. It may be necessary to probe more deeply so that the self-assessment helps students monitor their own learning to help them become independent learners (Gipps 1994). Finally, practice educators should encourage students to consider what they want feedback on, as this will help the latter to develop self-awareness of personal and professional development (Bailey 1998). Opportunities and time should be made available to engage in the essential process of formative assessment with learners to provide them with targeted and evidence-based feedback, so that action plans for further learning and development of competence can be made. Adequate documentation of progress can thus be made. Duffy (2004) warns that the omission of formative assessment with opportunities for student self-assessment leads to inadequate documentation of progress, and is a potential cause for the student’s inability to achieve the required level of competence. In academic settings, feedback is commentary about a learner’s performance that aims to provide the learner with insight into performance, with the aim of improving that performance (Billings et al 2010, Clynes & Raftery 2008). It is an interactive process. Feedback may be categorized into two broad groups: constructive/corrective/negative and reinforcing/positive (Clynes & Raftery 2008). The crucial role of feedback in learning cannot be emphasized enough, with Rowntree (1987:27) stating that it is the ‘lifeblood of learning’. Torrance & Pryor (1998) emphasize the importance of identifying not just what learners have achieved but also what they might achieve and what they are now ready to achieve. Butler (1988) has shown that feedback comments alone had more effect on students’ subsequent learning than comparable situations where marks alone or feedback and marks were given. The award of grades or simply confirming correct responses or performance has little effect on subsequent performance (Crooks 1988) as such feedback is very non-specific. It does not tell the student what has been done to merit such a grade or response, or what could be done to earn a better grade or to improve performance. Rowntree (1987) considers that such non-specific feedback becomes increasingly useless to the student as the size and diversity of performance being assessed increases during the placement. This factor is important for the practice educator to consider, as students are required to engage in, and learn through, a diverse range of clinical activities. Specific and detailed feedback, with descriptions of what actually occurred, is required on a myriad of activities and situations that the student will have taken part in. Examples from the student’s practice should be used to illustrate points being made in the feedback. This should be clear to the student and offered in terms of specific standards achieved or not achieved. Formative assessment processes, then, require quality feedback of the kind and detail that tells learners what to do in order to improve; such quality feedback is more effective as students know explicitly and reliably what they are expected to do. This is because the mere provision of feedback is insufficient for optimal learning. What students need in order to make any improvement is to have knowledge of the desired standard or goal, to be able to compare their own performance with the desired performance and, subsequently, to explore options for improving practice and take part in the appropriate activities to close the gaps – they need to know in some detail what to do, and what they can do, in order to improve. Feedback will then help the student to grow, boost confidence, and increase motivation and self-esteem (Clynes & Raftery 2008). There is detailed discussion of how to manage constructive feedback sessions in Chapter 7. Whereas formative assessments take place throughout the student’s clinical placement, summative assessments usually take place at the end of the placement, where the aggregate of learning is represented. Summative assessment focuses on the whole and is used to provide information about how much students have learned and to what extent learning outcomes have been met. There is a judgement of achievement. In the event of negative outcomes, nothing can now be done to remedy the situation. The competency-based assessment system allows only two judgements of competence: competent or not yet competent (Wolf 1995:22). Wolf goes on to say: This has to be the position of the assessment of clinical practice in the professions, as the main purpose of assessment is for accountability purposes. The specified competencies (in the UK these are referred to as standards for pre-registration nursing and midwifery students, and pre-registration health care courses regulated by the Health and Care Professions Council) for each clinical placement must be achieved at the summative assessment in order to progress in the training. Students who are not yet competent at progression points (HCPC 2011, NMC 2010, 2009) are generally not allowed to progress further in their training until they have successfully achieved competence. Two positions are taken with formative assessment in this discussion: first, it is a facilitative process that aims to guide and maximize learning; secondly, it serves to provide a series of assessments so that a summative assessment can be compiled from them. Rowntree (1987) suggests that final ‘end-of-the-placement’ assessments may be dispensed with altogether if a satisfactory summative assessment can be compiled from the series of formative assessments. However, Harlen et al (1992) maintain that summative assessments should be separated into two types: ‘summing-up’ and ‘checking-up’. In the former, information collected over a period of time is simply ‘summed’ at intervals to assess how students are getting on. This collection of pieces of assessment evidence from formative assessments is kept in the student’s portfolio of learning in order to preserve the richness of the data. The summing-up provides a picture of current achievements. ‘Checking-up’ is when summative assessment is done through the use of assessment tasks specifically devised for the purpose of assessing competence at a particular time. For example, at the end of the placement, on summing-up the evidence of competence of a learner in relationship to admitting a client to the ward, the assessor requires some more evidence of competence. In this example, checking-up can be in the form of observing the learner admit a client or simulating the activity. In your clinical area you may identify competencies that are crucial for the safe delivery of care and choose to use ‘checking-up’ as a matter of course when assessing the learner summatively. The three little words ‘assessment takes time’ was probably written with much feeling and understanding by Phillips et al (2000:150) after their intensive investigation of the assessment of clinical practice in pre-registration nursing and midwifery education. Assessment does indeed take time. I would contend that good assessment takes even more time. Time has to be allocated for ‘assessment-only’ activity to enable assessors to engage in the process of continuous assessment so that assessments serve the intended purposes. Recently, the NMC (2008) recommended that consideration is given to the practice educator’s workload to enable more meaningful conduct of assessment activities. The assessment activities to be undertaken within the continuous assessment process may be represented in Figure 6.1. It can be seen from Figure 6.1 that one of the central assessment activity is that of student–practice educator meetings. Bedford et al (1993) found that these valuable meetings do not function as effectively as they might because they are hurriedly carried out. If students feel that they pose an additional burden in a busy clinical area, the quality and quantity of learning is extremely negatively affected (Phillips et al 2000). Protected, that is timetabled, time should be prioritized and allocated for ‘assessment-only activities’ (NMC 2008, Phillips et al 2000, Bedford et al 1993). Professional responsibility and accountability for learners require us to ensure that learning takes place, and allocating and spending time with learners is part of that contract we enter into with learners in our care. Readers are directed to Chapter 8 in the section ‘Staff commitment to teaching and learning’ for some suggestions on how to support student learning and assessment activities. This first formalized meeting/interview is important for students: they will be feeling anxious in a new place of work (Phillips et al 2000) and unsure about what to expect from their practice educator they may be meeting for the first time. When asked about their first day on clinical placement, most students in Phillips et al’s study (2000:72), provided, as their first word descriptor, ‘scary’, ‘frightening’, ‘terrified’ and ‘anxious’. Students will also be feeling, for example, uncertain about how the ward functions, whether they will fit in and be accepted and what they are going to learn, particularly if the student has never worked in that area of speciality. The student will thus be looking for support and guidance from the practice educator. Anxiety can be a barrier to learning (Rogers 1983). The first meeting/interview gives the practice educator an ideal opportunity to start forming a facilitative relationship with the student and introducing the student to, for example, the clinical area, its routine, the learning opportunities available and the members of staff. What we know about what helps learners in a new clinical area tells us that ‘beginners’ feel more secure if their practice can be guided by the structure of a specified routine (Benner et al 1996). Practice educators in Fraser et al’s study (1997) found that these meetings gave them valuable insight into a student’s understanding of the clinical setting and their aspirations during the placement. Their ‘readiness to learn’ (Knowles 1990) can thus be determined. Vygotsky (1930, in Spouse 1998) introduced the concept of ‘zone of proximal development’ (ZPD) to describe the range of activities in which learners are capable of engaging. The ZPD comprises a two-stage theory of development whereby a learner who is intellectually ready to move to the next stage could be assisted to reach this potential through support and guidance from a more experienced other. Having an accurate assessment of a learner’s level of capability is crucial in assisting a learner to develop a higher level of competence. Work in educational psychology tells us that, for effective learning and development to take place, the task must be matched to the student’s current level of understanding, and pitched at that level to provide practice in the first instance, and subsequently a slightly higher level in order to extend and develop the student’s skills (Bigge 1982). If the new task is too easy, the student can become bored; if too difficult, the student can become demotivated. By matching the learning tasks to the student’s level, the learning contract/assessment plan is individualized and the emphasis on assessment is placed on the student’s progress and learning. The first meeting/interview with the student should be done as soon as possible – preferably within the first 2 days of the commencement of the placement. This is important to enable the practice educator and the student to draw up a learning contract that contains an assessment plan. This plan for learning and assessment should utilize the information from the student self-assessment to contribute to the identification of learning needs. It should also consider the student’s ZPD to maximize learning and professional development. As soon as the learning contract and assessment plan are negotiated and agreed, the direction that both the practice educator and student require for the teaching/learning and assessment processes to commence is provided. It is recognized that students appreciate the development of an initial plan and think that this is good practice (Fraser et al 1997). In Chapter 2, it was discussed that one of your responsibilities as practice educator is to be familiar with the structure, organization and content of the programme of students you are assessing. This will allow you to have cognizance of the learning outcomes that your student will be required to achieve during the placement. The first meeting/interview allows you to evaluate what prior learning has taken place to inform and guide subsequent plans for learning. Phillips et al (2000) found that students on new placements often had to endure being treated as though they knew nothing – previous learning and accomplishments were ignored. Apart from this being disabling and demotivating, it can lead the practice educator to shape learning experiences inappropriately. Phillips et al (2000), very rightly in my view, contend that all students know something and some know a great deal. The points to discuss with the student should include the following: • find out and attempt to allay any anxieties • confirm the student’s stage of training and current module of study to ascertain course learning outcomes • discuss any personal learning outcomes the student may have planned • jointly examine and discuss the student’s portfolio of learning to ascertain prior learning and progress • ask about any written assignments or projects that have to be prepared • discuss the learning opportunities the placement can provide to generate assessment evidence to enable achievement of competencies and learning outcomes • discuss arrangements to supervise and support the student in your absence

Assessment as a process to support learning

Introduction

Continuous assessment of clinical practice

Formative assessment

Student self-assessment in formative assessment

Feedback in assessment

Summative assessment

Engaging in the process of continuous assessment

The first meeting/interview

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Assessment as a process to support learning

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access