Collecting patient data

Performing a 10-minute examination

♦ You won’t always want or need to examine a patient in 10 minutes. However, rapid examination is crucial when you must intervene quickly—such as when a patient’s physical, mental, or emotional status changes.

♦ You may also perform a rapid examination to confirm a diagnostic finding. For example, if arterial blood gas analysis indicates a low oxygen content, you’ll quickly check the patient for other signs of oxygen deprivation, such as increased respiratory rate and cyanosis.

General guidelines

♦ Try to collect the patient data not only quickly but also systematically. To save time, cover several components at once. For example, make general observations while checking the patient’s vital signs or asking history questions.

♦ Be flexible. You may not use the same sequence each time. Let the patient’s chief complaint and your initial observations guide your examination. Sometimes, a quick history may be impossible. Instead, you may need to rely on your observations and the patient’s chart.

♦ Keep the patient calm and cooperative. If you don’t know him, introduce yourself by name and title. Stay calm, and reassure him that you can help. If you can reduce his anxiety, he’ll be more likely to give you accurate information.

♦ Avoid drawing quick conclusions. In particular, don’t assume that the patient’s current symptom is related to his admitting diagnosis.

When every minute counts, follow these steps.

Check airway, breathing, and circulation

♦ As your first priority, this step may consist of just a momentary observation. However, if a patient seems to be unconscious or is having trouble breathing, examine him more thoroughly to detect the problem and allow immediate intervention.

Make general observations

♦ Note the patient’s mental status, general appearance, and level of consciousness (LOC) for clues about the nature and severity of his condition.

Check vital signs

♦ Take the patient’s temperature, pulse, respiratory rate, pulse oximetry reading, and blood pressure. They provide a quick overview of his condition as well as valuable information about the heart, lungs, and blood vessels.

♦ The seriousness of the patient’s chief complaint and your general observations of his condition will determine how extensively you measure vital signs. Vital signs are further discussed in

chapter 2.

A patient’s age, activity level, and physical and emotional condition may affect his vital signs. Compare your findings with the patient’s baseline, if available.

Conduct the health history

♦ Using pointed questions, explore the patient’s view of his chief complaint. Find out what’s bothering him most. Ask him to quantify the problem. For instance, does he feel worse today than he did yesterday? Such questions will help focus your interview and examination.

♦ If the patient can’t respond, use other sources, such as family members, admission forms, the medical history, and the patient’s chart.

Perform the physical examination

♦ Begin by explaining what you’re planning to do. Concentrate on areas related to the patient’s chief complaint — the abdomen, for example, if the patient complains of abdominal pain. Compare the results with baseline data, if available.

♦ Sometimes, you may have to perform a complete head-to-toe or body systems examination—for instance, if a patient is unresponsive (yet has no breathing or circulatory problems) or is confused and, thus, unreliable.

♦ In most cases, the patient’s chief complaint, your general observations, and your findings about the patient’s vital signs will guide your examination.

Guidelines for an effective interview

When you have time to collect all pertinent data, begin by interviewing the patient. An effective interviewing technique will help you collect essential health history information efficiently. Use these guidelines to enhance your skills.

Be prepared

♦ Before the interview, review all available information. Read the current and, if available, previous clinical records. This will focus the interview, prevent the patient from tiring, and save you time.

♦ Review the information with the patient to make sure it’s correct.

♦ Keep in mind that the patient’s current complaint may be unrelated to his history.

Create a pleasant interviewing atmosphere

♦ Select a quiet, well lit, relaxing setting. Eliminate as many distractions and interruptions as possible. A relaxing atmosphere eases the patient’s anxiety, promotes comfort, and conveys your willingness to listen.

♦ Ensure privacy and maintain confidentiality. You may let friends or family members remain if the patient requests it or if he needs their help.

♦ Make sure the patient feels as comfortable as possible. If he’s tired, short of breath, or frightened, provide care and reschedule the interview.

♦ Take your time. Give the patient your undivided attention. If you have limited time, focus on specific areas of interest and return later instead of hurrying through the entire interview.

Establish a good rapport

♦ Explain the purpose of the interview. Emphasize how the patient benefits when the health care team has the information needed to diagnose and treat a disorder.

♦ Show your concern for the patient’s story. Maintain eye contact, and occasionally repeat what he tells you. If you seem preoccupied or uninterested, he may choose not to confide in you.

♦ Urge the patient to help you to gather information to be used to develop a realistic care plan that will serve his perceived needs.

Set the tone and focus

♦ Encourage the patient to talk about his chief complaint. This helps you focus on his most troublesome signs and symptoms and lets you determine the patient’s emotional state and level of understanding.

♦ Keep the interview informal but professional. Allow time for the patient to answer questions fully and to add his own perceptions.

♦ Speak clearly and simply. Avoid medical terms.

Make sure the patient understands you, especially if he’s elderly. If you think he doesn’t, ask him to restate what you’ve discussed.

♦ Pay close attention to the patient’s words and actions, interpreting not only what he says but also what he doesn’t say.

If the patient is a child, direct as many questions as possible to him. Rely on the parents for information if the child is very young.

Choose your words carefully

♦ Ask open-ended questions to encourage the patient to provide complete and pertinent information. Avoid yes-or-no questions.

♦ Listen carefully to the patient’s answers. Use his words in your later questions to encourage him to elaborate on his signs, symptoms, and other problems.

Take notes

♦ Document all information provided on the appropriate forms or electronically, per facility policy.

Determining overall health status

♦ For a quick evaluation of the patient’s overall health, ask these questions.

– Has your weight changed? Do your clothes, rings, and shoes fit?

– Do you have nonspecific signs and symptoms, such as weakness, fatigue, night sweats, or fever?

– Can you keep up with your normal daily activities?

– Have you had any unusual symptoms or problems recently?

– How many colds or other minor illnesses have you had in the last year?

– Have you had any illnesses or surgeries in the past?

– What prescription drugs, over-thecounter drugs, or herbal supplements do you take?

Determining activities of daily living

♦ For a more complete evaluation of the patient’s health and health history, ask these questions.

Diet and elimination

– How would you describe your appetite?

– What do you normally eat in a 24-hour period?

– What foods do you like and dislike? Is your diet restricted at all?

– How much fluid do you drink during an average day? Are the beverages caffeinated or not?

– Are you allergic to any food?

– Do you prepare your meals, or does someone prepare them for you?

– Do you go to the grocery store, or does someone else shop for you?

– Do you eat snacks and, if so, what kind?

– Do you have enough money to purchase the groceries you need?

– When do you usually go to the bathroom? Has this pattern changed recently?

– Do you take any foods, fluids, or drugs to maintain your normal elimination patterns?

Exercise and sleep

– Do you have a special exercise program? What is it? How long have you been following it? How do you feel after exercising?

– How many hours do you sleep each day? When? Do you feel rested afterward?

– Do you fall asleep easily?

– Do you take any drugs or do anything special to help you fall asleep?

– What do you do when you can’t sleep?

– Do you wake up during the night?

– Do you have sleepy spells during the day? When?

– Do you routinely take naps?

– Do you have any recurrent, disturbing dreams?

– Have you ever been diagnosed with a sleep disorder, such as narcolepsy or sleep apnea?

Recreation

– What do you do when you aren’t working?

– What do you do for enjoyment?

– How much leisure time do you have?

– Are you satisfied with what you can do in your leisure time?

– Do you and your family share leisure time?

– How do your weekends differ from your weekdays?

Tobacco, alcohol, and drugs

– Do you use tobacco? If so, what kind? How much do you use each day? Each week? When did you start using it? Have you ever tried to stop?

– Do you drink alcoholic beverages? If so, what kind (beer, wine, whiskey)?

– How much alcohol do you drink each day? Each week? What time of day do you usually drink?

– Do you usually drink alone or with others?

– Do you drink more when you’re under stress?

– Has drinking ever hampered your job performance?

– Do you or does anyone in your family worry about your drinking?

– Do you feel dependent on alcohol?

– Do you feel dependent on coffee, tea, or soft drinks? How much of these beverages do you drink in an average day?

– Do you use drugs that aren’t prescribed by a physician (marijuana, cocaine, heroin, steroids, sleeping pills, tranquilizers)?

Determining family dynamics

♦ When determining how and to what extent the patient’s family fulfills its functions, remember to ask about both the family into which the patient was born (family of origin) and, if different, the patient’s current family.

♦ Because the following questions target a nuclear family—that is, mother, father, and children—you may need to modify them somewhat for other types of families, such as single-parent families, families that include grandparents, patients who live alone, or unrelated individuals who live as a family.

♦ Remember, you’re determining the patient’s perception of family function.

Affective function

♦ To determine how family members regard each other, ask these questions.

– How do the members of your family treat each other?

– How do they feel about each other?

– How do they regard each other’s needs and wants?

– How are feelings expressed in your family?

– Can family members safely express both positive and negative feelings?

– What happens when family members disagree?

– How do family members deal with conflict?

– Do you feel safe in your environment?

Socialization and social placement

♦ To determine the flexibility of family responsibilities, which aids discharge planning, ask these questions.

– How satisfied are you and your partner with your roles as a couple?

– How did you decide to have (or not to have) children?

– Do you and your partner agree about how to bring up the children? If not, how do you work out differences?

– Who takes care of the children? Is this arrangement mutually satisfactory?

– How well do you feel your children are growing up?

– Are family roles negotiable within the limits of age and ability?

– Do you share cultural values and beliefs with your children?

Health care function

♦ To identify the family caregiver and thus facilitate discharge planning, ask these questions.

– Who takes care of family members when they’re sick? Who makes physician appointments?

– Are your children learning about personal hygiene, healthful eating, and the importance of adequate sleep and rest?

– How does your family adjust when a member is ill and unable to fulfill expected roles?

Family and social structure

♦ To determine the value the patient places on family and other social structures, ask these questions.

– How important is your family to you?

– Do you have any friends whom you consider family?

– Does anyone other than your immediate family (for example, grandparents) live with you?

– Are you involved in community affairs? Do you enjoy the activities?

Economic function

♦ To explore financial issues and their relation to power roles within the family, ask these questions.

– Does your family income meet the family’s basic needs?

– Who makes decisions about family money allocation?

– If you take prescription drugs, do you have enough money to pay for them?

Performing a physical examination

♦ Use the techniques of inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation to perform a physical examination.

Performing inspection

♦ Inspection uses vision, smell, and hearing to observe normal conditions as well as deviations.

♦ Performed correctly, inspection can reveal more information than the other techniques.

Performing palpation

♦ Palpation uses pressure to determine structure size, placement, pulsation, and tenderness.

♦ To perform light palpation (to feel for surface abnormalities), press gently on the skin, indenting it ½″ to ¾″; (1 to 2 cm). To perform deep palpation (to feel internal organs and masses), depress the skin 2″; to 3″; (5 to 7.5 cm) with firm, deep pressure.

Performing percussion

♦ Direct percussion reveals tenderness and uses one or two fingers to tap directly on a body part.

♦ Indirect percussion elicits sounds that give clues to the makeup of the underlying tissue. To perform, place the middle finger of your nondominant hand against the body part. Using the middle finger of your dominant hand, quickly tap the finger of your other hand (the one resting against the body part) just beneath its distal joint.

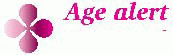

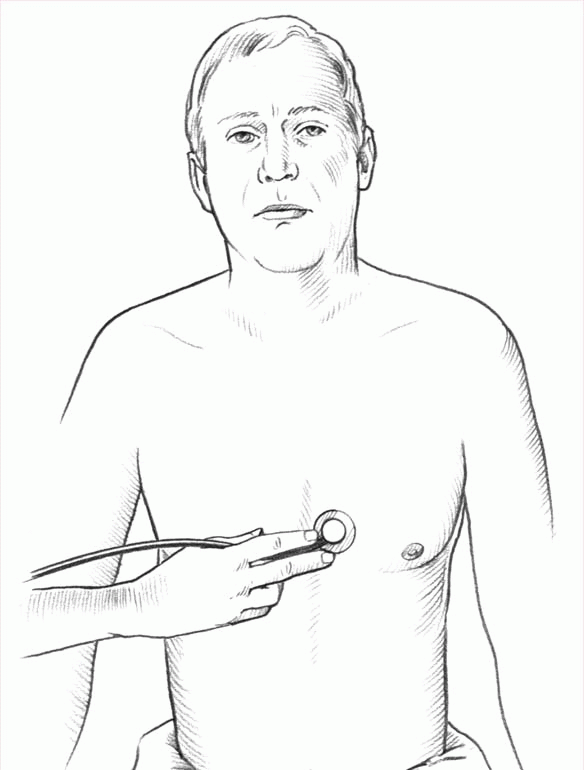

Performing auscultation

♦ Auscultation involves using a stethoscope to listen for various breath, heart, and bowel sounds. (See Performing auscultation.)

Checking the skin, hair, and nails

Initial skin questions

♦ Determine if your patient has any known skin disease, such as psoriasis, eczema, or hives.

♦ Ask him to describe any changes in skin color, temperature, moisture, or hair distribution.

♦ Ask the patient to describe any itching, rashes, or scaling. Is his skin excessively dry or oily?

♦ Ask the patient about skin care, sun exposure, use of sun protection factor (SPF) products, SPF number used, and use of protective clothing.

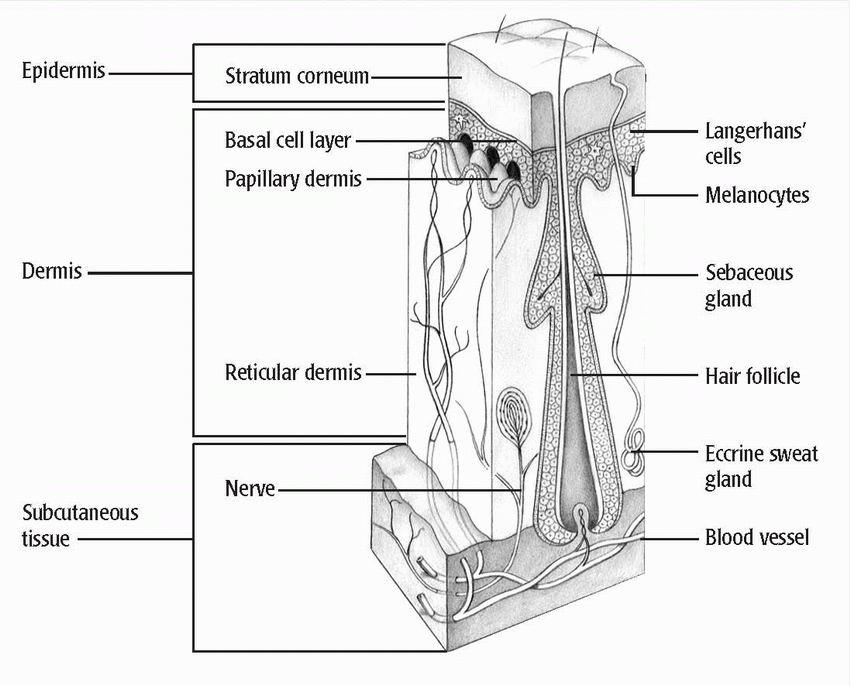

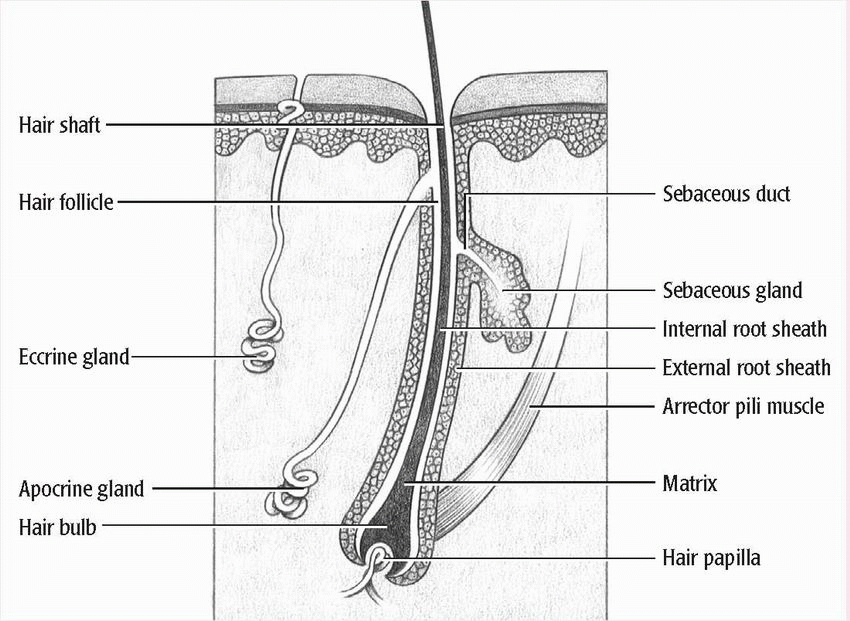

♦ Ask if your patient has noticed easy bruising or bleeding, changes in warts or moles, or lumps. Ask about the presence and location of scars, sores, and ulcers. Consider how these changes might affect the various skin layers. (See Structure of the skin.)

Inspecting and palpating the skin

♦ Before you begin your examination, make sure that the lighting is adequate for inspection. Put on a pair of gloves. To examine the patient’s skin, you’ll use both inspection and palpation— sometimes simultaneously.

♦ During your examination, focus on such skin tissue characteristics as

color, texture, turgor, moisture, and temperature. Evaluate skin lesions, edema, hair distribution, and fingernails and toenails.

Color

♦ Begin by systematically inspecting the skin’s overall appearance. Remember, skin color reflects the patient’s nutritional, hematologic, cardiovascular, and pulmonary status. (See Evaluating skin color variations.)

♦ Observe the patient’s general coloring and pigmentation, keeping in mind racial differences as well as normal variations from one part of the body to another. Examine all exposed areas of the skin, including the face, ears, back of the neck, axillae, and backs of the hands and arms.

♦ Note the location of any bruising, discoloration, or erythema. Look for pallor, a dusky appearance, jaundice, and cyanosis. Ask the patient if he has noticed any changes in skin color anywhere on his body.

Texture

♦ Inspect and palpate the texture of the skin, noting thickness and mobility.

♦ Does the skin feel rough, smooth, thick, fragile, or thin? Changes can indicate local irritation or trauma, or they may be a result of problems in other body systems. For example,

rough, dry skin is common in hypothyroidism; soft, smooth skin is common in hyperthyroidism.

♦ To determine if the skin over a joint is supple or taut, have the patient bend the joint as you palpate.

Turgor

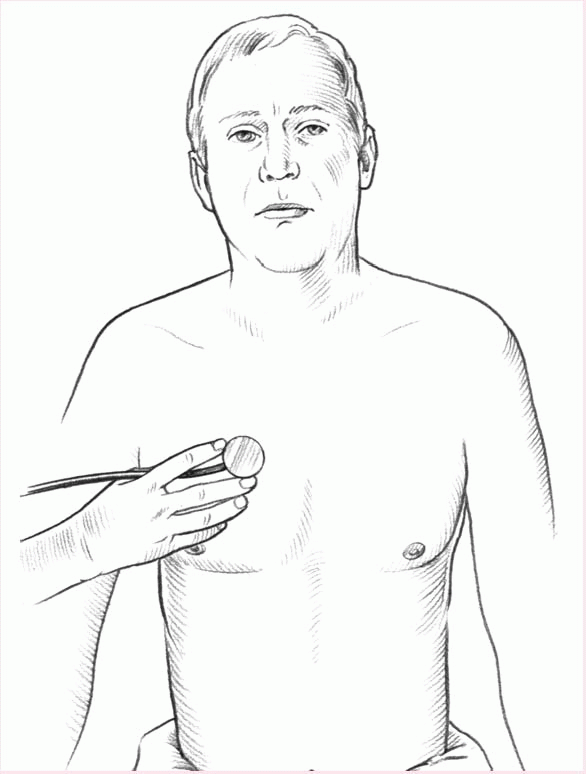

♦ Checking the turgor, or elasticity, of the patient’s skin helps you to evaluate hydration. To check turgor, gently squeeze the skin on the forearm. If it quickly returns to its original shape, the patient has normal turgor. If it resumes its original shape slowly or maintains a tented shape, the skin has poor turgor. (See Evaluating skin turgor.)

Dehydration and aging decrease turgor. Progressive systemic sclerosis increases it.

♦ In an elderly patient, the skin of the forearm tends to be paper-thin, dry, and wrinkled, so it doesn’t accurately represent the patient’s hydration status.

♦ To accurately determine skin turgor in an elderly patient, try squeezing the skin of the sternum or forehead instead of the forearm.

Moisture

♦ Observe the skin for excessive dryness or moisture. If the patient’s skin is too dry, you may see reddened or flaking areas. Elderly patients commonly have dry, itchy skin. Moisture that appears shiny may result from oiliness.

♦ If the patient is overhydrated, the skin may be edematous and spongy.

♦ Localized edema can occur in response to trauma or skin abnormalities such as ulcers. When you palpate local edema, document related discoloration or lesions.

Temperature

♦ To check skin temperature, touch the surface with the back of your hand. Inflamed skin will feel warm from increased blood flow. Cool skin results from vasoconstriction. With hypovolemic shock, for instance, the skin feels cool and clammy.

♦ Make sure to distinguish between generalized and localized warmth or

coolness. Generalized warmth, or hyperthermia, is related to fever from a systemic infection or viral illness. Localized warmth occurs with a burn or localized infection. Generalized coolness occurs with hypothermia; localized coolness, with arteriosclerosis.

Skin lesions

♦ During your inspection, you may note vascular changes in the form of red, pigmented lesions. These lesions may indicate disease.

♦ Among the most common lesions are hemangiomas, telangiectases, petechiae, purpura, and ecchymoses.

Examining dark skin

♦ Be prepared for certain color variations when examining dark-skinned patients. For example, some darkskinned patients have a pigmented line, called Futcher’s line, extending diagonally and symmetrically from the shoulder to the elbow on the lateral edge of the biceps muscle. This line is normal. Also normal are deeply pigmented ridges in the palms.

♦ To detect color variations in darkskinned and black patients, examine the sclerae, conjunctivae, buccal mucosa, tongue, lips, nail beds, palms, and soles.

♦ A yellow-brown color in darkskinned patients or an ash-gray color in black patients indicates pallor, which results from a lack of the underlying pink and red tones normally present in dark skin.

♦ Among dark-skinned black patients, yellowish pigmentation may not indicate jaundice. To detect jaundice in these patients, examine the hard palate and the sclerae.

♦ Look for petechiae by examining areas with lighter pigmentation, such as the abdomen, gluteal areas, and the volar aspect of the forearm. To distinguish petechiae and ecchymoses from erythema in dark-skinned patients, apply pressure to the area. Erythematous areas will blanch, but petechiae and ecchymoses won’t.

♦ When you check for edema in darkskinned patients, remember that the affected area may have decreased color because fluid expands the distance between the pigmented layers and the external epithelium. When you palpate the affected area, it may feel tight.

♦ Cyanosis can be difficult to identify in both white and black patients. Because certain factors, such as cold, affect the lips and nail beds, make sure to check the conjunctivae, palms, soles, buccal mucosa, and tongue as well.

♦ To detect rashes in black or darkskinned patients, palpate the area to identify changes in skin texture.

Initial hair questions

♦ Determine if your patient has any hair problems, such as hair loss or increased growth and distribution of hair.

♦ Ask the patient to identify physiological factors that could cause hair disorders, such as skin infections, ovarian or adrenal tumors, increased stress, or systemic diseases, such as hypothyroidism or malignancies.

♦ If the patient isn’t receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy, ask when the patient first noticed hair loss or thinning and whether it was sudden or gradual.

♦ Ask when the patient first noticed any increase in hair growth or altered distribution of hair.

♦ Ask if the change occurred in just a few spots or all over the patient’s body.

♦ Ask about medication, vitamin, or herbal use.

♦ Ask about itching, pain, discharge, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, altered

bowel habits, urine changes, fatigue, pain, temperature intolerance, fever, or weight change.

♦ If the patient is female, find out if she has menstrual irregularities, and note her pregnancy history.

♦ If the patient is male, ask about sexual dysfunction, such as decreased libido or impotence.

♦ Ask about hair care. Does the patient often use a hot blow dryer or electric curlers? What about dye, bleach, or perms?

♦ Check for a family history of alopecia, and ask what age relatives were when they started losing hair.

♦ Also ask about nervous habits, such as pulling the hair or twirling it.

♦ Ask about dietary habits and use of supplements.

In children, alopecia may stem from chemotherapy or radiation therapy, seborrheic dermatitis (known as cradle cap in infants), alopecia mucinosa, tinea capitis, and hypopituitarism. Tinea capitis may produce a kerion lesion that’s boggy, raised, tender, and hairless. Trichotillomania, a psychological disorder more common in children than adults, may produce patchy baldness with stubby hair growth from habitual hair pulling.

Inspecting the hair

♦ Start by inspecting and palpating the hair over the patient’s entire body, not just on his head. (See

Hair structure.) To palpate the patient’s hair, rub

a few strands between your index finger and thumb.

♦ Note the distribution, quantity, texture, and color of the patient’s hair. The quantity and distribution of head and body hair varies among patients. However, hair should be evenly distributed over the entire body.

♦ The texture of scalp hair also varies among patients. Differences in grooming and hairstyling may affect the texture and quality of hair. Dryness or brittleness can result from harsh hair treatments or hair care products, or it might be from a systemic illness.

♦ Extremely oily hair is usually related to an excessive production of sebum or poor grooming habits.

♦ Check for patterns of hair loss and growth. If you notice patchy hair loss, look for regrowth.

♦ Examine the scalp for erythema and scaling, which may indicate dermatitis.

♦ Note areas of excessive hair growth, which may indicate a hormone imbalance or a systemic disorder such as Cushing’s syndrome.

Initial nail questions

♦ Ask the patient about any changes in nail growth or color.

♦ Ask the patient about any conditions that could cause these changes, such as infection, nutritional deficiencies, systemic illnesses, or stress.

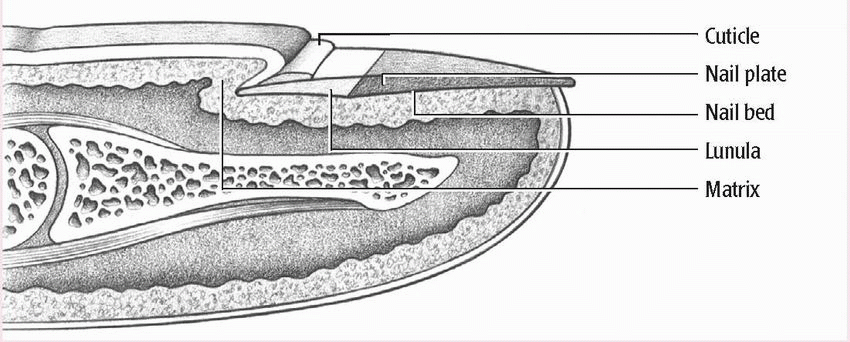

♦ Determine if the patient has had any changes in nail shape, color, or brittleness. (See Nail anatomy.)

♦ Ask when the patient first noticed nail changes. Were these changes sudden or gradual?

♦ Ask about other signs or symptoms, such as bleeding, pain, itching, or discharge.

♦ Ask about any history of nail problems, nail biting, or serious illness.

♦ Ask about the use of artificial nails and any problems related to their use.

Inspecting the nails

♦ Checking the nails is vital for two reasons: Their appearance can be a critical indicator of systemic illness, and their overall condition tells you a

lot about the patient’s grooming habits and self-care.

♦ Examine the nails for color, shape, thickness, consistency, and contour. First, look at the color of the nails.

Light-skinned patients typically have pinkish nails. Dark-skinned patients typically have brown nails. Brown-pigmented bands in the nail beds are normal in darkskinned people and abnormal in light-skinned people.

Thick nails are usually caused by psoriasis, fungal infections, or decreased vascular blood supply to the nail bed.

In patients who smoke cigarettes, nails may turn yellow from nicotine stains. Psoriasis and fungal infections also can turn nails yellow.

♦ Nail beds can be used to determine a patient’s peripheral circulation (capillary refill). Press on the nail bed and then release, noting how long the color takes to return. It should return immediately, or at most within 3 seconds.

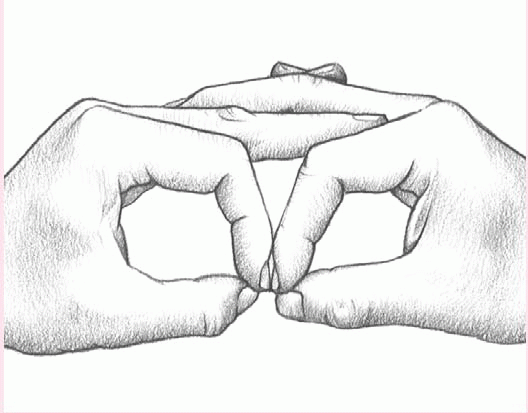

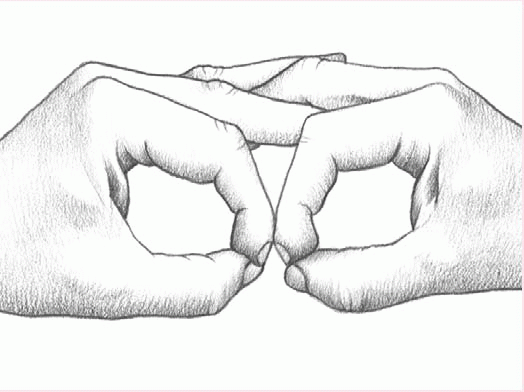

♦ Next inspect the shape and contour of the nails. The surface of the nail bed should be either slightly curved or flat. The edges of the nail should be smooth, rounded, and clean. The normal angle of the nail base is 160 degrees. (See Evaluating clubbed fingers.)

In children, clubbing is most common in those with cyanotic congenital heart disease and cystic fibrosis. Surgical correction of heart defects may reverse clubbing. In elderly patients, arthritic deformities of the fingers or toes may disguise the presence of clubbing.

♦ Curved nails are a normal variation. They may appear to be clubbed until you determine that the nail angle is still 160 degrees or less.

♦ Finally, palpate the nail bed to check the thickness of the nail and the strength of its attachment to the bed.

Make sure the patient understands you, especially if he’s elderly. If you think he doesn’t, ask him to restate what you’ve discussed.

Make sure the patient understands you, especially if he’s elderly. If you think he doesn’t, ask him to restate what you’ve discussed.

In children, alopecia may stem from chemotherapy or radiation therapy, seborrheic dermatitis (known as cradle cap in infants), alopecia mucinosa, tinea capitis, and hypopituitarism. Tinea capitis may produce a kerion lesion that’s boggy, raised, tender, and hairless. Trichotillomania, a psychological disorder more common in children than adults, may produce patchy baldness with stubby hair growth from habitual hair pulling.

In children, alopecia may stem from chemotherapy or radiation therapy, seborrheic dermatitis (known as cradle cap in infants), alopecia mucinosa, tinea capitis, and hypopituitarism. Tinea capitis may produce a kerion lesion that’s boggy, raised, tender, and hairless. Trichotillomania, a psychological disorder more common in children than adults, may produce patchy baldness with stubby hair growth from habitual hair pulling.

Light-skinned patients typically have pinkish nails. Dark-skinned patients typically have brown nails. Brown-pigmented bands in the nail beds are normal in darkskinned people and abnormal in light-skinned people.

Light-skinned patients typically have pinkish nails. Dark-skinned patients typically have brown nails. Brown-pigmented bands in the nail beds are normal in darkskinned people and abnormal in light-skinned people. Thick nails are usually caused by psoriasis, fungal infections, or decreased vascular blood supply to the nail bed.

Thick nails are usually caused by psoriasis, fungal infections, or decreased vascular blood supply to the nail bed. In patients who smoke cigarettes, nails may turn yellow from nicotine stains. Psoriasis and fungal infections also can turn nails yellow.

In patients who smoke cigarettes, nails may turn yellow from nicotine stains. Psoriasis and fungal infections also can turn nails yellow. In children, clubbing is most common in those with cyanotic congenital heart disease and cystic fibrosis. Surgical correction of heart defects may reverse clubbing. In elderly patients, arthritic deformities of the fingers or toes may disguise the presence of clubbing.

In children, clubbing is most common in those with cyanotic congenital heart disease and cystic fibrosis. Surgical correction of heart defects may reverse clubbing. In elderly patients, arthritic deformities of the fingers or toes may disguise the presence of clubbing.