Chapter 7. Assessing and planning care in partnership

Anne Casey

ABSTRACT

All aspects of care, from assessment to evaluation, are affected by the context in which the care takes place and in particular by the attitudes and values of the nurse and the care team. Working in partnership requires a specific focus for nursing assessment, planning and evaluation which is different to traditional disease focused models.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

• Appreciate the importance of accurate and detailed observation and assessment (and recording of same).

• Identify and select from a range of assessment approaches for different children and clinical situations.

• Undertake, with supervision, holistic assessment of the infant/child/young person as a basis for planning general nursing care.

• Use assessment data to make initial judgements about the child and family’s need for general nursing care, to be validated by an experienced nurse.

• Describe how assessment findings and clinical evidence inter-relate when planning care.

• Incorporate reassessment and evaluation of outcomes in the care plan.

• Recognise the complex nature of clinical reasoning and the roles of the child, family, nurse and multiagency team in assessment, planning and evaluation of care.

The nature of assessment

In any walk of life, assessment is the basis for making decisions about what to do. Unless an action is completely spontaneous, it is usually preceded by the person gathering together relevant facts, thinking about them to make sense of the situation and then weighing up the possible alternatives for what to do next. During and after the action, further thought is given to whether the choice of action was the right one – Is this having the effect I expected it to? What else could I try? Perhaps I jumped to the wrong conclusion about what was wrong?

Assessment is both a process and a result: assessing the level of oil in the engine might give a result of ‘its getting low’ and a plan to top up next time I’m passing the service station. Of course, if I then notice a patch of oil under the car I revise my initial assessment result to ‘there could be a leak’ and plan to go straight to a repair centre.

In health care, the process of assessment attempts to answer the question ‘What is (probably) going on here?’ With some degree of certainty about what is happening, it is possible to make a plan that will address the problem. But there is much more to assessing and planning care than simply discovering the problem and deciding what to do. This chapter explores assessment and care planning in the context of child/family/nurse partnerships to provide insights into these complex interpersonal and clinical processes that are the cornerstones of clinical practice. Recording, communicating and evaluating planned care are also considered, with an emphasis on the clinical and information governance responsibilities of the nurse. The chapter does not cover assessment for the specific purpose of investigating, diagnosing and treating medical conditions; Barnes (2003) is the recommended text for nurse practitioners undertaking what were traditionally medical roles. Assessment of and planning for community and population child health needs are also not covered here (see Chapter 8).

Assessment and planning in context

The clinical process

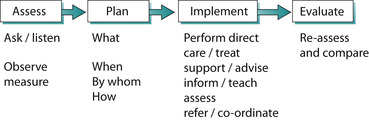

When first learning about something as complex as nursing, it helps to use diagrams or models that simplify the situation but demonstrate how things relate and where they fit in the real world of practice. Conceptual models and process models are used in nursing and other disciplines to clarify concepts important to the discipline and define relationships between them. The ‘nursing process’ was one such model introduced to the UK in the 1970s to help nurses focus on each individual patient and his or her needs, rather than on the medical condition and ‘what we always do for patients with x’. It is clear that health professionals other than nurses use a similar process and that parents and children follow the same basic steps when managing illness at home. This ‘clinical process’ as it applies to nursing is outlined in Figure 7.1 to help you visualise the practical steps that are taken in the care and treatment of children and young people.

|

| Fig. 7.1 The clinical process. |

The first step in the process is prompted by any one of a number of ‘triggers’: a mother notices a rash on her baby’s face, the community nurse visits a sick child at home, the teenager walks into the school drop-in centre, a 4-hourly temperature measurement is due and so on. The steps of assessing, planning, implementing and evaluating can take seconds in an emergency and months or years, for example, in the case of a child who has sustained a severe head injury. Although the model suggests a straight line, where one step neatly follows the one before, the process is anything but linear. Observing a bruise will lead to a plan for further assessment; when teaching a child about his asthma he may reveal concerns about exercise, which will prompt assessment and a different plan; assessment may lead to a decision to take no further action and so on. The three pillars of assessment (listening, observing and measuring) are constant activities throughout the care process. Planned assessments such as hourly monitoring of pain level and ad hoc or opportunistic assessments such as noticing a change in one child while attending to another, become the basis for changes to planned care, new assessments and new plans.

It can be helpful to distinguish between initial or generalised assessment of the kind that would be carried out at a first contact or admission in a non-emergency situation and focused assessment, where attention is directed at a specific state, behaviour, concern or situation. The goals of an initial assessment are to identify:

1. Immediate and ongoing care needs related to the reason for the visit, contact or admission.

2. Other issues/areas of concern.

3. Health promotion needs and opportunities.

It is important to establish a baseline of assessment data that can be used to agree care aims, monitor progress and evaluate outcomes.

Results of initial assessments are used to plan for and to provide care, support, information and education and to communicate with/refer to other professionals. Generalised and focused assessments are discussed later in this chapter after an introduction to clinical reasoning and exploration of the contextual factors that affect both the process and outcome of assessment (and the rest of the care process).

Clinical reasoning

A process model of the kind described above has limitations: one criticism of the nursing process is that it emphasises patient problems (it is sometimes referred to as a ‘problem-solving process’) and therefore is unsuited to health promotion and ‘well person’ elements of nursing roles. Although it clearly shows how a nurse could provide individualised, planned care, the process focuses on ‘doing’ steps, and thus hides the clinical reasoning that is required to sift through the available assessment data and to weigh up the evidence to make good clinical decisions.

Another way of looking at the same process is to consider the cognitive processes that underpin assessment, planning and evaluation, rather than the action steps. ‘Clinical reasoning’ is a general term covering the cognitive processes of diagnostic reasoning (also known as clinical judgement) and clinical decision making. Higgs (2000) provides an excellent overview of clinical reasoning in the health professions. Knowing about these clinical and cognitive processes can help direct your approach to care and will inform your practice in helping children, young people and families to carry out assessments themselves and make decisions about what actions to take in the light of their own findings.

Activity

Activity

Activity

ActivityImagine that you woke up this morning with a slight pain in your knee that has worsened during the day. List the things you might ask yourself or do to try to establish what the problem is. What knowledge have you drawn on to inform your ‘diagnostic reasoning’?

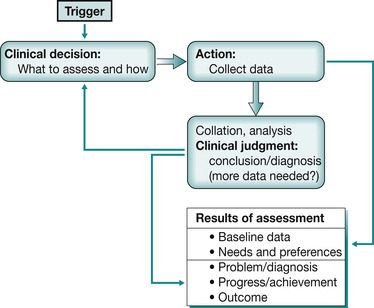

Figure 7.2 shows how the data that are collected by listening, observing, measuring and communicating with other professionals are sifted and sorted to select what is relevant and then analysed to reach a conclusion on whether the situation is normal for this child, a problem, a risk and so on. If there are insufficient data to reach a conclusion, a further decision is required – what more data do I need? To make good clinical judgements, the person doing the assessment draws on existing knowledge and past experience, and uses cognitive skills such as pattern recognition (‘I’ve seen this kind of thing before’) and ruling out by hypothesis testing (‘It can’t be infection because there’s no fever’) to reach conclusions. These assessment ‘conclusions’ are known in some nursing literature and practice as nursing diagnoses.

|

| Fig. 7.2 Clinical reasoning in assessment. |

In the US and many other countries (and to a small extent in the UK) nurses use the concept of nursing diagnosis to describe and communicate to others the primary focus of nursing care. A nursing diagnosis is ‘a clinical judgement about individual family or community responses to actual or potential health problems/life processes’ (North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) 2008). It is usually expressed as a diagnostic statement and reflects some aspect of the child and family’s response to a health issue or problem, as distinct from the medical diagnosis of the problem.

One of the benefits of reaching a firm conclusion is that this can be discussed openly. Your initial conclusion about what is making a child cry, for example, could lead you to take certain actions, which might be totally inappropriate unless you confirm your ‘diagnosis’ with the child. A fully expressed nursing diagnosis contains not only the diagnosis but also the cause or ‘related factors’ and the assessment data that support your conclusion (‘defining characteristics’ of the diagnosis) (Carpenito-Moyet 2004). ‘Pain in the arm related to the splint rubbing’ requires very different action from ‘pain in arm related to fracture’.

Deciding what action to take (clinical decision making) uses different knowledge and cognitive skills than judging whether there is a need for action, as Table 7.1 illustrates. Based on the ‘diagnosis’, and when appropriate, goals or expected outcomes can be discussed and agreed with the child and family so that everyone is clear about what can be expected. Knowledge from research and other evidence (see Chapter 14), and personal experience of what works in this kind of situation, inform cognitive decision-making processes such as narrowing of options and weighing-up pros and cons. Possible actions need to be balanced against available resources to arrive at an agreed plan of what is to be done, by whom and when.

| Cognitive processes – examples | Knowledge used | |

|---|---|---|

| Making clinical judgements: reaching a conclusion about what is (probably) going on | Collation of data/cues Data analysis Pattern recognition Hypothesis generation and evaluation Dealing with uncertainty | Previous experience of this child or similar situations, patterns, etc. Knowledge of effects of disease, surgery, etc., on child and family Research evidence and patient ‘stories’ of what it is like to be a child, parent, family member in this situation |

| Making clinical decisions: deciding what to do – choosing a course of action (in relation to goals) | Critical thinking/weighing up research evidence Identifying and evaluating options Setting priorities and managing constraints: time, resources, crises | Knowledge about what has worked for this child in the past Previous experience of what works in similar situations Evidence, guidelines, protocols for the best approach to take |

Context for care

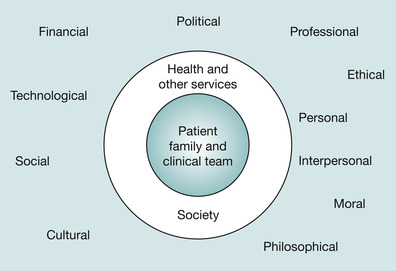

Patient care and the clinical process do not take place in isolation. No matter how good the assessment is and how well planned the care, there are many other factors that influence whether the child’s and family’s expectations of care are achieved and their experience of nursing and health care is a positive one. The context of care, from the interpersonal relationships between family and staff to the prevailing political climate, heavily impact on the quality of the services and care provided. Figure 7.3 illustrates the multitude of factors that have an influence on the care process, many of which are addressed in the chapters in Section 1 of this book. At different times and in different situations the impact of the various factors will be different but four of them are particularly important in nursing:

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice

• Interpersonal: relationships and interactions between and among the child, the family and the clinical team.

• Financial: availability of and ease of access to specific services and resources, e.g. equipment, staff and time.

• Philosophical: the ethos of the team that pervades all aspects of care delivery.

• Ethical: recognition of rights, equity, etc.

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practiceInterpersonal context

How could interpersonal relationships between members of a clinical team (an aspect of the interpersonal context) influence the quality of your nursing care? For example, what would happen if the nursing team does not feel able to question medical staff decisions?

|

| Fig. 7.3 Context of care: influences on the care process. |

Partnership principles applied to assessing and planning care

In Chapter 6, Lynda Smith, Valerie Coleman and Maureen Bradshaw described parental involvement in care as moving along a continuum from nurse led to parent led. Other conceptual models of nursing use similar constructs to help explain aspects of the relationship between nurses and patients, for example, Orem’s view of the patient as totally dependent through to self caring (Orem 2001). These kinds of models and terms such as ‘nurse led’, ‘patient centred’, ‘child friendly’ represent particular philosophies: ways of thinking and then acting that directly influence the child’s and family’s experience of care. Even the language we use implies a particular way of thinking and acting. You might hear the term ‘non-compliant’ applied in a situation, for example, where a teenager with diabetes is admitted to hospital. ‘Non-compliance’ suggests that heavy-handed sanctions will be needed to get the patient to manage diet, exercise and insulin properly. If the teenager is described instead as ‘making choices that can put her at risk’ then the management approach is more likely to be one that reflects an understanding of adolescent needs.

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practicePhilosophical context

Nurses often provide information to the child and family about the child’s condition or treatment, reflecting a view of children and families as passive recipients of healthcare. What view would you be reflecting if instead of providing information you helped the child to find out where to get information for herself?

The term ‘partnership’ is widely used in health and social care to represent the ideal or preferred relationship between agencies and between professionals and clients. In the nursing care of children and families it has come to mean a changing, negotiated, shared responsibility for care between child, family and nurse, with support and teaching provided (including teaching of nurses by the child and family). Family involvement in care may be a result of the negotiation of care responsibility but is not necessarily so. Conversely, nursing involvement in care may not be what the child and family want: respite care at home for the child with complex needs may be better provided by a social care assistant with specific training. A key principle of partnership working is that responsibility does not have to be shared equally: the extent to which the child, family member and nurse are ready for and able to contribute to the partnership dictates changes in responsibility – for the child towards independent self-care and for some parents towards leading and delegating care. In some situations, the nursing team may only be able to offer limited services so the burden of care remains with the family.

Partnership complements other constructs valued by nurses caring for children and young people such as ‘child-centred care’ and respect for children’s rights, particularly the right to be informed and to have a say in decision making (see Chapter 10 and Chapter 18). There is very little evidence of how children and parents view partnership working (as distinct from research into their views on involvement or participation in care), and little to indicate whether true partnerships are possible in a context where professionals have more power and there are limited resources. In Coyne’s (1995) study, parents reported difficulties with lack of information, non-negotiation of roles, and feelings of anxiety and loneliness when caring for their child in hospital.

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice

CHILD CONVERSATION

CHILD CONVERSATION

Kate aged 11 years with asthma

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practiceNegotiated roles

Kirk (2001) investigated whether there was any negotiation of caring roles between professionals and parents of children with complex needs:

From the parents’ perspective, their initial assumption of responsibility for the care of their child was not subject to negotiation with professionals. Prior to discharge, feelings of obligation, their strong desire for their child to come home and the absence of alternatives to parental care in the community were key motivating factors in their acceptance of responsibility from professionals (Kirk 2001 p 593).

Professionals had concerns about whether parents were given a choice and the degree of choice they could exercise in the face of professional power. As parents gained experience in caring for their child, and as their relationships with professionals developed, role negotiation started to happen. Kirk concluded that professional expectations of parental involvement probably acted as a barrier to negotiation of roles and that parental choices were initially constrained by their feelings of obligation.

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practiceWho knows best?

A study by Waters et al (2003) explored differences between adolescent and parental reports of physical, emotional, mental and social health and well-being. Over 2000 young people (with and without chronic illness) and their parents were involved in the study. All the adolescents were much less optimistic about their health and well-being than their parents. There were significant differences in their reports of general health, mental health, frequency and amount of pain and the impact on the family of their health problems.

CHILD CONVERSATION

CHILD CONVERSATIONKate aged 11 years with asthma

Kate: Once I started doing it myself [the asthma diary] I could see much better how I was doing. I could tell the nurse how much Ventolin I’d needed and sometimes we could see what was making it worse. Once we decided for me to try taking Ventolin before going outdoors or for PE when it was cold outside.

Kate’s mum: She was better at keeping the diary than me, at least at first. Now she only uses it when she’s having problems and that helps her see what needs doing.

Applying a partnership approach to assessment alters the goals that were listed on page 2, which now become:

• With the child and family, to identify:

• their immediate and ongoing care needs related to the reason for the visit, contact or admission

• other issues/areas of concern

• health promotion needs and opportunities

• their experience and expectations of care and services

• their readiness and preferences in relation to participation in care and decision making

• To establish a baseline (as before).

Traditional, profession-centred models of care still exist where the mother, not the child or young person, is asked about the child’s condition and progress. The clinician interprets the assessment information and informs the parent what needs to happen next. However, in most services it is accepted that the children and young people themselves are the best source of information and that seeking their views and involving them in decision making and self-care are beneficial not just in terms of outcome but in making their whole experience of health care more positive.

Using the communication tools that are most familiar to children and young people, such as mobile phones and the internet, goes some way to improving the child friendliness of services. Although these approaches are still being evaluated, it is possible to envisage young people with diabetes, for example, managing their condition at home with internet-based decision support, e-mail advice and mobile phone text reminders for medication times. But there is still a significant shift needed in the way professionals view the child and young person’s world, particularly the child/young person with a chronic condition or disability. More locally delivered services and better use of technology will support moves from a world where the child/young person and the family must adapt their lives to fit around the condition and its management to a world where the condition and its management are adapted to their lifestyles. With more children’s nurses as part of the primary care team supporting children and families at home there will hopefully be greater attention focused on assessment and intervention in relation to the safety and suitability of the child’s environment, his or her access to community services and the appropriateness of those services. Simple solutions like having appointments outside of college hours seem obvious but there are very few clinics that consider the needs and lifestyles of children and young people.

Before moving on to the practice of assessment and care planning, it is appropriate to summarise the clinical process as it can look when informed by partnership and other nursing values/philosophies (Table 7.2). Listening to and respecting the child/young person’s and family’s views and involving them in decision making is not a luxury that only applies in long-term care situations; it is a fundamental right that applies equally in emergencies, in ambulatory and short-stay settings – everywhere that children and young people receive health care.

| Assess | Ask the child, ask the parents/carer |

| Invite the child, parents/carer to observe and measure | |

| Observe and measure | |

| Confirm your impressions and conclusions with the child and parents/carer, especially their view of the priorities | |

| Plan | Agree appropriate goals with the child and parents/carer |

| Discuss possible actions and assist them in making choices | |

| Agree initial plan for what needs to be done, who will do it, when and how | |

| Plan for regular shared review of the plan, care responsibilities and teaching and support needs | |

| Implement | Perform direct care as planned (child, parent/carer, nurse) |

| Facilitate learning and information sharing | |

| Provide support and supervision | |

| Monitor progress and reassess as planned (child, parent/carer, nurse) | |

| With consent, refer to other professionals and coordinate care | |

| Evaluate | Invite the child, parents/carer to observe and measure outcomes and report their experience of care |

| Review and reflect on the care process from child and family perspective and from the professional nursing perspective |

Assessment and planning in practice

Having considered the process of assessing and planning, the context in which it occurs and the ways in which values and philosophies influence the process, it is now time to address the important question of how to assess and plan care. In this section the focus for nursing assessment is discussed, and assessment approaches and tools introduced. The section concludes with examples of approaches and tools to support evidence-based care planning.

A growing thread throughout health and social care in the UK is the single, shared patient record as a necessary requirement for ensuring continuity in an age when many different disciplines and services may be providing care for one child. This theme will be picked up in the final section of the chapter; recording, communicating and auditing care. A single record suggests a single assessment and one care plan for the child, something that many professionals believe would get rid of many of the communication failures and frustrations that parents and children experience.

The focus of assessment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access