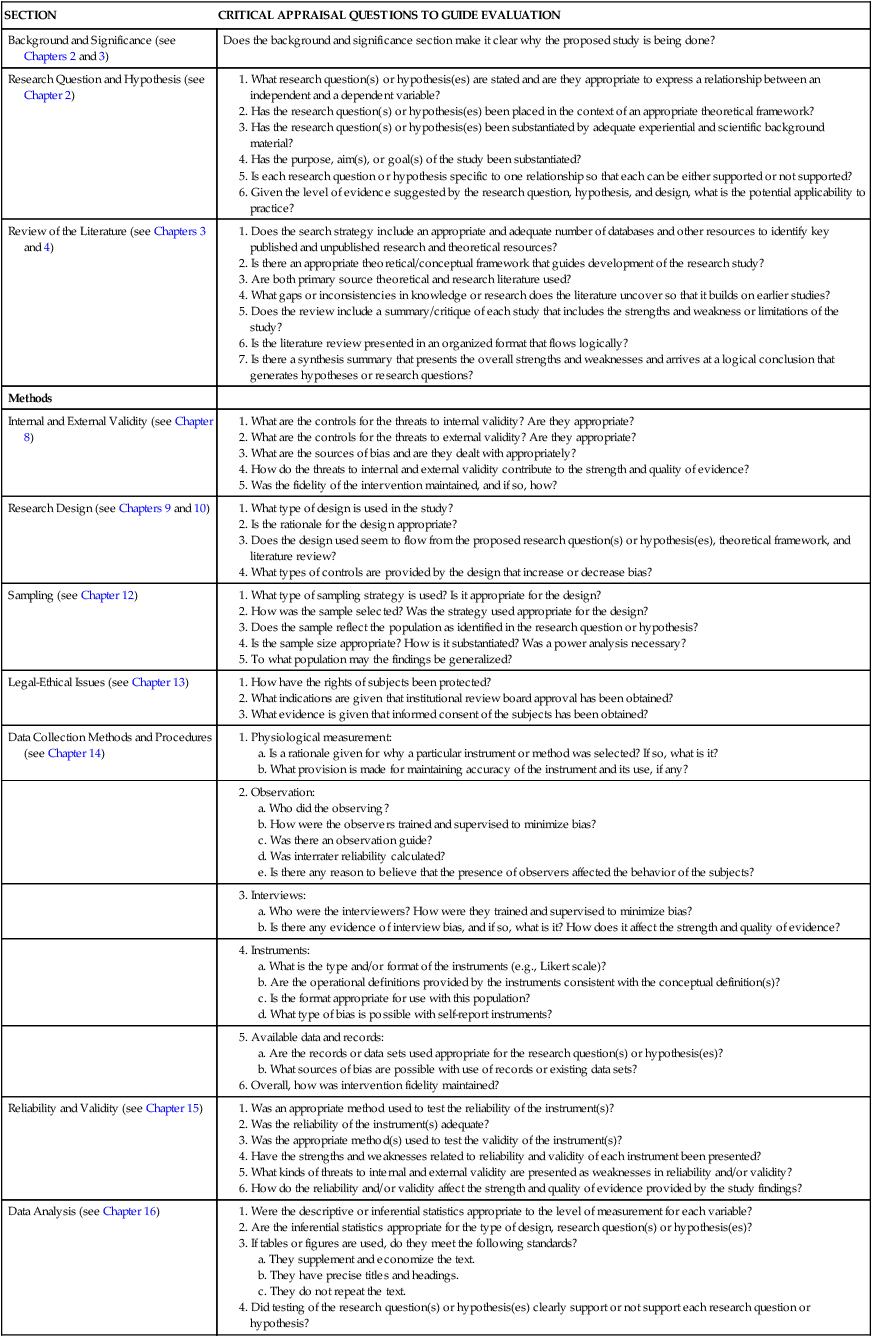

CHAPTER 18 After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following: • Identify the purpose of the critical appraisal process. • Describe the criteria for each step of the critical appraisal process. • Describe the strengths and weaknesses of a research report. • Assess the strength, quality, and consistency of evidence provided by a quantitative research report. • Discuss applicability of the findings of a research report for evidence-based nursing practice. Go to Evolve at http://evolve.elsevier.com/LoBiondo/ for additional research articles for review questions, critiquing exercises, and practice in reviewing and critiquing. Critical appraisal is an evaluation of the strength and quality, as well as the weaknesses, of the study, not a “criticism” of the work, per se. It provides a structure for reviewing the sections of a research study. This chapter presents critiques of two quantitative studies, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) and a descriptive study, according to the critiquing criteria shown in Table 18-1. These studies provide Level II and Level IV evidence. TABLE 18-1 SUMMARY OF MAJOR CONTENT SECTIONS OF A RESEARCH REPORT AND RELATED CRITICAL APPRAISAL GUIDELINES As reinforced throughout each chapter of this book, it is not only important to conduct and read research, but to actively use research findings to inform evidence-based practice. As nurse researchers increase the depth (quality) and breadth (quantity) of studies, the data to support evidence-informed decision making regarding applicability of clinical interventions that contribute to quality outcomes are more readily available. This chapter presents critiques of two studies, each of which tests research questions reflecting different quantitative designs. Criteria used to help you in judging the relative merit of a research study are found in previous chapters. An abbreviated set of critical appraisal questions presented in Table 18-1 summarize detailed criteria found at the end of each chapter and are used as a critical appraisal guide for the two sample research critiques in this chapter. These critiques are included to illustrate the critical appraisal process and the potential applicability of research findings to clinical practice, thereby enhancing the evidence base for nursing practice. Background: Throughout the illness trajectory, women with breast cancer experience issues that are related to physical, emotional, and social adjustment. Despite a general consensus that state-of-the-art treatment for breast cancer should include educational and counseling interventions to reduce illness or treatment-related symptoms, there are few prospective, theoretically based, phase-specific, randomized controlled trials that have evaluated the effectiveness of such interventions in promoting adjustment. Purpose: The aim of this study is to examine the physical, emotional, and social adjustment of women with early-stage breast cancer who received psychoeducation by videotapes, telephone counseling, or psychoeducation plus telephone counseling as interventions that address the specific needs of women during the diagnostic, postsurgery, adjuvant therapy, and ongoing recovery phases of breast cancer. Design: Primary data from a randomized controlled clinical trial. Setting: Three major medical centers and one community hospital in New York City. Methods: A total of 249 patients were randomly assigned to either the control group receiving usual care or to one of the three intervention groups. The interventions were administered at the diagnostic, postsurgery, adjuvant therapy, and ongoing recovery phases. Analyses were based on a mixed model analysis of variance. Main Research Variables and Measurement: Physical adjustment was measured by the side effects incidence and severity subscales of the Breast Cancer Treatment Response Inventory (BCTRI) and the overall health status score of the Self-Rated Health Subscale of the Multilevel Assessment Instrument. Emotional adjustment was measured using the psychological well-being subscale of the Profile of Adaptation to Life Clinical Scale and the side effect distress subscale of BCTRI. Social adjustment was measured by the domestic, vocational, and social environments subscales of the Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale. Findings: Patients in all groups showed improvement over time in overall health, psychological well-being, and social adjustment. There were no significant group differences in physical adjustment, as measured by side effect incidence, severity, or overall health. There was poorer emotional adjustment over time in the usual care (control) group as compared to the intervention groups on the measure of side effect distress. For the telephone counseling group, there was a marked decline in psychological well-being from the adjuvant therapy phase through the ongoing recovery phase. There were no significant group differences in the dimensions of social adjustment. Conclusion: The longitudinal design of this study has captured the dynamic process of adjustment to breast cancer, which in some aspects and at various phases has been different for the control and intervention groups. Although patients who received the study interventions improved in adjustment, the overall conclusion regarding physical, emotional, and social adjustment is that usual care, which was the standard of care for women in both the usual care (control) and intervention groups, supported their adjustment to breast cancer, with or without additional interventions. Implications for Nursing: The results are important to evidence-based practice and the determination of the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of interventions in improving patient outcomes. There is a need to further examine adjustment issues that continue during the ongoing recovery phase. Key Points: Psychoeducation by videotapes and telephone counseling decreased side effect distress and side effect severity and increased psychological well-being during the adjuvant therapy phase. All patients in the control and intervention groups improved in adjustment. Adjustment issues are still present in the ongoing recovery phase. The American Cancer Society (2007) estimated that 178,480 women in the United States will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer and 62,032 women would be diagnosed with noninvasive breast cancer. Early-stage breast cancer includes (a) tumors up to 2 cm that have spread to axillary lymph nodes; (b) tumors 2 and 5 cm that have or have not spread to axillary lymph nodes; or (c) tumors greater than 5 cm but have not spread outside the breast (National Cancer Institute, 2007). Although early diagnosis and successful medical interventions have improved longterm prognosis, women often experience uncertainty about their future (ACS, 2007). Because adjustment to breast cancer does not end with the completion of medical treatment, it is important to examine physical, psychological, and social adjustment as an ongoing process (Iscoe, Williams, Szalai, & Osoba, 1991; Varricchio, 1990). Based on an earlier descriptive study (Hoskins et al., 1996a), four phases of the breast cancer experience were identified: diagnosis (biopsy results obtained), postsurgery (2 days following definitive surgery), adjuvant therapy (postdiscussion with oncologist of the need for chemotherapy or radiation therapy), and ongoing recovery (2 weeks following completion of chemotherapy or radiation or 6 months after surgery if no chemotherapy or radiation was received). At each of these four phases, health-relevant information and social support were key coping strategies in promoting physical, social, and emotional adjustment. Based on findings and an extensive review of the literature, Hoskins et al. (2001) developed and pilot tested a series of four phase-specific, 30-minute videotapes to provide a standardized evidence-based psychoeducational intervention, as well as a phase-specific telephone counseling intervention that focused on physical, emotional, and social needs of women and their partners. A randomized clinical trial was conducted to examine the physical, emotional, and social adjustment of women with early-stage breast cancer who received the standardized psychoeducation by video, telephone counseling, or psychoeducation by video with telephone counseling, as interventions. The purpose of the interventions was to address the specific needs of women during the diagnostic, postsurgery, adjuvant therapy, and recovery phases of breast cancer. The primary hypotheses related to patient’s adjustment were the following: (a) physical adjustment would be greater in each of the study intervention groups as compared to the control group who received usual care; (b) emotional adjustment would be greater in each of the study intervention groups as compared to the control group who received usual care; and (c) social adjustment would be greater in each of the study intervention groups as compared to the control group who received usual care. A previously published article by the research team (Budin, Cartwright, & Hoskins, 2008; Budin, Hoskin, et al., 2008) provides an overview of a randomized trial with a primary focus on the methodology and general results of the trial. The purpose of this article is to focus, specifically, on the primary data related to the adjustment of patients with early-stage breast cancer, with an emphasis on the implications for evidence-based practice and future research. Over the last 30 years, there has been a proliferation of studies regarding the impact of breast cancer on a woman’s well-being. Loveys and Klaich (1991) reported that as a chronic disease, the acceptance of a breast cancer diagnosis, treatment decisions, emotional distress related to physical change and loss, alterations in lifestyle, uncertainty, and need for information and support are ongoing issues. In general, it was agreed that the broad domains of adjustment to breast cancer may be conceptualized as psychological (Walker, Nail, & Croyle, 1999), physical (Cohen, Kahn, & Steeves, 1998; Wyatt & Friedman, 1998), and social (Northhouse, Dorris, & Charron-Moore, 1995). Adjustment has also been commonly conceptualized as role performance (Derogatis, 1983), self-esteem and body image (Kemeny, Wellisch, & Schain, 1988), psychosexual and psychosocial adjustment (Capone, Good, Westie, & Jacobson, 1980; Hasida, Gilbar, & Lev, 2001; Wimberly, Carver, Laurenceau, Harris, & Antonia, 2005), emotional symptoms (Hoskins et al., 1996a; Pasacreta, 1997), symptom experiences and distress (Boehmke & Dickerson, 2005), and quality of life (Badger et al., 2005; Sammarco, 2001). Based on their research, Sklalla, Bakitas, Furstenberg, Ahles, and Henderson (2004) identified the informational needs of patients and their spouses to be the treatment process, specifically information regarding chemotherapy or radiation therapy, specific side effects, and the implication for their lives. Ahles et al. (2006) studied patients (n = 644) who were randomized to a control group receiving usual care and an intervention group, which received information regarding problem solving and pain management skills by telephone intervention. Patients in the intervention group reported less pain, improved physical and emotional vitality, and improved functional status when compared with patients receiving usual care at 6 months. Several randomized controlled trials of women with breast cancer have supported the use of psychoeducation and telephone counseling in promoting adjustment. Based on the Roy Adaptation Model, Samarel, Tulman, and Fawcett (2002) randomized 125 women with early-stage breast cancer to either the intervention group, which received 13 months of combined individual telephone and in-person group support and education, or to Control Group 1, which received 13 months of telephone-only individual support and education, or Control Group 2, which received one-time mailed educational material. The results indicated that the intervention group and Control Group 1 reported less mood disturbance, loneliness, and higher quality relationships than Control Group 2. There were no group differences in cancer-related worry or well-being. The results suggest that telephone support may provide an alternative to support groups. Rawl et al. (2002), based on a randomized controlled trial of 109 patients diagnosed with breast, lung, and colon cancer receiving chemotherapy, reported that those who received four telephone interventions and five in-person clinic visits had significantly less depression and improved quality of life midway through chemotherapy and 1 month postchemotherapy. It was concluded that this nurse-directed intervention improved psychological symptoms for patients with cancer. Badger et al. (2005) examined the effectiveness of telephone counseling compared to usual care on symptom management and quality of life for women (n = 48) with breast cancer. Findings indicated that women in the intervention group had decreased depression, fatigue, and stress over time and increases in positive affect. Ahles et al. (2006) randomized patients (n = 644) with pain and psychological problems to a control group receiving usual care and an intervention group, which received information regarding problem solving and pain management skills by telephone intervention. Patients in the intervention group reported improved pain, physical and emotional vitality, and functional status verses when compared with patients receiving usual care at 6 months. Samdgrem and McCaul (2006) also tested interventions involving health education and emotional expression provided through a telephone intervention for women (n = 218) with Stage 1, 2, and 3 breast cancer. Oncology advanced practice nurses conducted the telephone intervention, with the results indicating that patients receiving telephone therapy had less perceived stress and better knowledge; however, there was no significant difference in quality of life or mood. The results indicate that telephone therapy is a viable intervention that promoted the retention of patients, but it was concluded that both the control and intervention groups showed improvement in quality of life and mood over time. Badger, Segrin, Dorros, Meek and Lopez (2007) conducted a randomized control trial of 96 women and their partners who were randomly assigned to either 6-week programs of telephone interpersonal counseling, self-managed exercise, or attention control. The results indicated that depression scores decreased over time for all groups and that women in the telephone counseling and exercise groups had lower anxiety scores. The theoretical framework that guided the development of the study’s interventions, mediating/moderating, and outcome variables included the Stress and Coping Model (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), the Crisis Intervention Model (Morely, Messick, & Aguilera, 1967), findings of the preliminary descriptive study (Hoskins et al., 1996a, 1996b), and the pilot study to test the feasibility of a randomized controlled trial (Hoskins et al., 2001; refer to Fig. 1). According to the framework, cancer can be appraised as harm, loss, threat, challenge, or some combination of these (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). As such, stress and its appraisal are assumed to be inherent dimensions of the breast cancer experience (Folkman & Greer, 2000). According to Lazarus and Folkman’s Stress and Coping Model (1984), the concept of adaptation refers to an individual’s adjustment in relation to their appraisal of support resources and coping skills. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) and Derdiarian (1986, 1987a, 1987b, 1989) view information seeking as a primary mode of coping, which permits the individual to appraise the harms, threats, and challenges imposed by the diagnosis and treatment. Cohen and Lazarus (1979) contend that informational interventions help patients see how they can assume an active role in treatment and thus maintain some control. The hypothesis of this study was that information by psychoeducational videotape would promote emotional, physical, and social adjustment. The intervention model of this study also focuses on crisis prevention by maximizing physical adjustment and emotional adjustment, role performance, perceived social support, and overall health status. As a crisis intervention, telephone counseling is based on the notion that each phase of the breast cancer experience, that is, diagnosis, postsurgery, adjuvant therapy, and ongoing recovery (Blutz, Speca, Brasher, Geggie, & Page, 2000; Hoskins et al., 1996a; Northouse, & Swain, 1987; Sadeh-Tessa, Drory, Ginzburg, & Stadler, 1999), is stressful and characterized by its own particular features. The telephone counseling intervention addressed the unique needs of patients experiencing breast cancer by (a) assessing their phase-specific perceptions and emotions; (b) clarifying questions about medical treatments, procedures, and side effects; (c) exploring the adequacy of social supports; and (d) assessing the effectiveness of coping mechanisms (Aguilera, 1998; Parad & Parad, 1990; Sadeh-Tessa et al., 1999). The preliminary studies by Hoskins et al. (1996a, 1996b, 2001) enhanced the development of the extant theoretical framework with regard to the conceptual and operational definition of the studies variables, as well as the development and implementation of the intervention protocols. The findings related to the potential moderating variables and adjustment outcomes will be addressed in a subsequent paper. A pilot study of the randomized trial was conducted by Hoskins et al. (2001) to evaluate the intervention protocols and obtain preliminary data regarding the effectiveness of the proposed interventions. The pilot study enrolled a nonprobability sample of 12 women with early-stage breast cancer and their partners. Four patient–partner pairs received one of three interventions: psychoeducational videotapes alone, telephone counseling alone, or a combination of phase-specific psychoeducational videotapes and telephone counseling, which were complementary approaches to usual care at the diagnostic, postsurgery, adjuvant therapy, and ongoing recovery phases of breast cancer. Even with limited statistical power, the preliminary results of the feasibility study supported the proposed interventions as promoting physical, emotional, and social adjustment among women with early-stage breast cancer. The value of conducting a full-scale randomized trial to better understand the relative treatment efficacy and differential benefit of the interventions was supported. A purposive sample of 249 patients was enrolled from three major medical centers and one community hospital in New York City. Analyses of pilot data were used to determine a reasonable expectation for group differences in mean changes among primary measures to sample size determination. These were expressed in terms of a mean change for the usual care, plus psychoeducational videos and telephone counseling groups that was one-fourth standard deviation above the grand mean, one-fourth standard deviation below the grand mean for the usual care group, and at the grand mean for the usual care plus psychoeducational videos, and usual care plus telephone counseling groups. This corresponds to two group standardized effect size of d = 0.50 between the extremes. This profile corresponds to a median effect size of f = 0.25 as defined by Cohen (1988). A target sample of 61 per group was selected to achieve a power of at least 80% for detecting group differences in mean change scores, assuming α = .01 and f ≥ .25. At the planning stage, the effect of reduced sample size from 61 per group to the sample sizes actually obtained (roughly 40 per group) in the study would serve to increase the minimum detectable effect sizes between group means at the extremes by about 26% (i.e., from d = 0.50 to d = 0.63). At each DC point, participants completed a packet of the following instruments: The Profile of Adaptation to Life Clinical Scale (PAL-C; Ellsworth, 1981) is a 41-item self-report inventory that is designed to measure variations in adjustment and functioning over time. Evidence of discriminant validity was provided by the subscales of psychological well-being and physical symptoms. In the preliminary descriptive study (Hoskins, 1990–1994), coefficient alphas were .75 for psychological well-being and .83 for physical symptoms. Test–Retest reliabilities were .80 and greater. The psychological well-being subscale addresses enjoyment in talking with others, finding work interesting, feelings of trust, involved, and feelings of being needed and useful. Scores for psychological well-being range from 5 to 20, with a higher score reflecting higher levels of psychological wellbeing. Physical symptoms subscale scores range from 7 to 28, with a higher score reflecting a higher level of physical symptoms experienced. The Self-Report Health Scale (SRHS; Lawton, Moss, Fulcomer, & Kleban, 1982) is a four-item subscale of the Multilevel Assessment Instrument (MAI), which assesses perceived health status. Construct validity was supported by a correlation of .67 between the summary domain for physical health and the SRHS and by a correlation of .63 between the ratings by the MAI interviewer and a clinician (Lawton et al., 1982). Factor analytic evaluation of the SRHS in the preliminary descriptive study (Hoskins et al., 1996a) revealed two factors, each consisting of two items and a reliability coefficient of .76 and test–retest of .92 at 3 weeks. The reliability estimate from the interitem correlation coefficient between perceived health status and Factor 1 (better health) was .60 and 0.69 for Factor 2 (no problems; Hoskins & Merrifield, 1993), indicating that each factor contributed substantially to the variance in perceived health status. Scores for overall health status range from 4 to 13, with a higher score reflecting better overall perceived health status. Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale (PAIS; Derogatis, 1983) is a 46-item scale that assesses the impact of the illness on seven domains of adjustment. Scores for role function in the domestic, vocational, and social environments were used in this study as the measures of social adjustment. Studies of discriminant validity among patients with breast cancer yielded correlations between the total PAIS score of .81 for the Global Adjustment to Illness Scale, .60 for the SCL-90-R General Severity Index, and .69 for the Affect Balance Scale (Hoskins, 1990–1994). The ranges in alpha coefficients in a preliminary, descriptive study by Murphy (1994) were .66 to .77 for domestic environment, 64 to .75 for vocational environment, and .83 to .85 for the social environment. The Breast Cancer Treatment Response Inventory (BCTRI; Budin, Cartwright-Alcarese, et al., 2008) provides a multidimensional assessment of the incidence, severity, and degree of distress of 19 side effects of breast cancer treatment. The BCTRI was pilot tested among 105 women with breast cancer from the time of diagnosis throughout treatment and ongoing recovery. Internal consistency was demonstrated with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of .64 for symptom incidence or occurrence, .77 for severity of symptoms, and .72 for amount of distress (ADE) experienced (Budin, Cartwright, & Hoskins, in press). Discriminant validity was supported by comparing the mean score for ADE reported by those receiving chemotherapy and those who were not (t = 4.4, p < .000). Criterion validity was supported by correlating ADE scores, measured by the BCTRI, and total scores from the Symptom Distress Scale (r = .86, p < .000; McCorkle & Young, 1978). 7.1. Demographic and baseline characteristics Demographic and baseline characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. The usual care (control) group and the three intervention groups were similar in terms of baseline sociodemographic characteristics. Subjects ranged in age from 51.8 to 54.1 across the four groups. With regard to ethnicity, Caucasians ranged from 67% to 71% across groups, and the percentages of African American subjects ranged from 10% to 22% across groups. Most of the participants across all groups were Christian (Protestant or Catholic). Greater than 70% of participants in all groups had children. More than half of the subjects in each of the four groups were living with a partner or spouse, and approximately three quarters of each group had at least some college education. The full-time employment rate ranged from 48% to 63% across groups. Most of the sample found the breast lesion by routine mammography (47.2%) or self-breast examination (26.9%), with 53% having a lumpectomy or partial mastectomy (20%) and lymph node dissection (74%; refer to Table 2 for medical variables). The only statistically significant difference (p = .003) among the groups was for “length of time known about lump.” A significant difference was found between the psychoeducational videotape group and the telephone counseling group, with respective means of 11.5 and 5.6 months. TABLE 1 DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES FOR PATIENTS (N = 249)

Appraising quantitative research

Critique of a quantitative research study

The research study

The effects of psychoeducation and telephone counseling on the adjustment of women with early-stage breast cancer

1. Introduction

2. Background literature

3. Theoretical framework

4. The development and pilot testing of the interventions

6. Methods

7. Results

VARIABLE

PATIENTS

n

%

Age in years, M (SD), range

53.8 (11.7), 33–98

Marital status

Single, never married

28

13.5

Single, living with partner

8

3.8

Married, living with partner

117

56.3

Divorced/Separated

27

12.9

Widowed

24

11.5

Other

4

1.9

(missing)

(41)

Race

White

148

69.2

African American

33

15.5

Latino/Hispanic

19

8.9

Asian or Pacific Islander

11

5.1

Other

3

1.4

(missing)

(35)

Religious preference

Protestant

43

21.1

Catholic

85

41.7

Jewish

42

20.6

Islam

2

1.0

Other

3

1.4

(missing)

(35)

(51)

Level of education

Some high school

10

4.7

High school graduate

38

17.9

Partial college

51

24.1

College graduate

56

26.4

Graduate degree

42

19.8

Postgraduate degree

7

3.3

Other

8

3.8

(missing)

(37)

(47)

Employment status

Unemployed

22

10.4

Part-time

26

12.3

Full-time

112

52.8

Retired

34

16.0

Medical disability

3

1.4

Other

14

7.1

(missing)

(37)

(47)

Work change

No

124

67.0

Yes

61

33.0

(missing)

(64)

(69)

Working less

33

55.9

Working more

2

3.4

On disability

3

5.1

Leave of absence

8

13.6

Other

13

22.0

(missing)

(190)

Combined annual income

Below $19,000

20

9.9

$19,000–$29,999

17

8.4

$30,000–$39,999

20

9.9

$40,000–$49,999

20

9.9

More than $50,000

126

62.1

(missing)

(46)

(59)

Children

No

52

24.5

Yes

160

75.5

(missing)

(37)

(46) ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Appraising quantitative research

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access