CHAPTER 12 Appraising and understanding systematic reviews and meta-analyses

What are systematic reviews?

More recently, systematic reviews have been embraced as a more comprehensive means of synthesising the literature.1 While literature reviews provide an overview of the research findings for a given topic they often address a broad range of issues, whereas systematic reviews address specific clinical questions in depth.2 Systematic reviews also differ from literature reviews in that they are prepared using transparent, explicit and pre-defined strategies that are designed to limit bias.2 In contrast to literature reviews, systematic reviews involve a clear definition of eligibility criteria; incorporate a comprehensive search of all potentially relevant studies; use explicit, reproducible and uniformly applied criteria in the selection of articles for the review; rigorously appraise the risk of bias within individual studies; and systematically synthesise the results of included studies.2

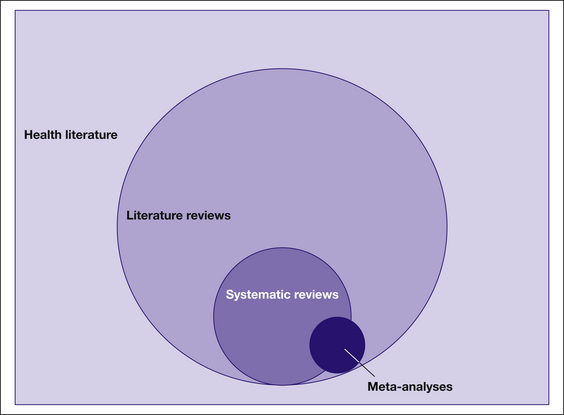

Where possible, a systematic review uses statistical methods to combine the results of two or more individual studies, and this type of review is then referred to as a meta-analysis. Meta-analyses generally provide a better overall estimate of a clinical effect than the results from individual studies. Often it is not possible to combine the results of individual studies because the interventions or outcomes used in the different studies are just too diverse, so results from these studies are synthesised narratively. It may help you to think about these different types of reviews visually. As you can see in Figure 12.1, literature reviews make up the vast majority of reviews that are found in the overall health literature. Systematic reviews can be considered a subset of reviews, and meta-analyses are a smaller set again. Note that the circle representing meta-analyses overlaps both systematic and literature reviews. This is because not all meta-analyses are carried out systematically. For example, it is technically possible for someone to take a collection of articles that report randomised controlled trials from their desk and undertake a meta-analysis of these articles. This would not be considered systematic as methods were not used to ensure that a systematic search for all relevant articles was conducted. Sometimes the terms systematic review and meta-analysis are used interchangeably, but in this chapter they are conceptualised as different entities. A systematic review does not need to incorporate a meta-analysis, but a meta-analysis should only be done within the context of a systematic review (although occasionally it is not).

Advantages and disadvantages of systematic reviews

By combining the results of similar studies, a properly conducted systematic review can improve the dissemination of evidence,2 hasten the assimilation of research into practice,3 assist in clarifying the heterogeneity of conflicting results between studies3 and establish generalisability of the overall findings.2 Systematic reviews are important for health professionals who are seeking answers to clinical questions, for researchers who are identifying gaps in research and defining future research agendas and for administrators and purchasers who are developing policies and guidelines.2

In addition to these problems, it may be possible for researchers to design a review that is based upon their retrospective knowledge of the relevant trials, which could influence the criteria used to select studies for inclusion in the review, assess the quality of those studies and extract data.4 A further problem of meta-analyses in particular is that, as they combine data from many individual studies, unfortunately they can also magnify the effect of the bias that may be in these individual studies if they are of low quality (or high risk of bias).

Systematic reviews for different types of clinical questions

Systematic reviews synthesise different study methodologies depending on the research question of interest.5 As we saw in Chapter 2 when we examined the hierarchies of evidence for various question types, systematic reviews are at the top of the hierarchy of evidence for questions about the effects of intervention, diagnosis and prognosis. For example, a properly conducted systematic review of randomised controlled trials is generally considered to be the best study design for assessing the effectiveness of an intervention because it identifies and examines all of the evidence about the intervention from randomised controlled trials that meet pre-determined inclusion criteria.6 This type of systematic review is by far the most common type of systematic review available. However, systematic reviews may be carried out to address other types of questions such as questions about diagnosis, prognosis and client experiences.

Systematic reviews that focus on questions of prognosis or prediction often undertake a synthesis of cohort studies. Consider the following example in which a systematic review of cohort studies of clients in the subacute phase of ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke was conducted with the aim of identifying prognostic factors for future place of residence at 6 to 12 months post-stroke.7 The authors searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Current Contents, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PsycLIT and Sociological Abstracts as well as reference lists, personal archives and consultations of experts in the field and guidelines to locate relevant cohort studies. They then assessed the internal, statistical and external validity of the 10 studies that they had selected for inclusion. Although the review found many factors that were predictive of a client’s future place of residence (for example, low initial functioning in activities of daily living, advanced age, cognitive disturbance, paresis of arm and leg), the authors concluded that there was insufficient evidence concerning possible predictors in the subacute stage of stroke with respect to place of future residence.

Systematic reviews of diagnostic test studies are carried out to determine estimates of test performance and consider variation between studies. This type of systematic review uses different methods to assess study quality and combine results than those used for systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials.8 An example of this type of review is one that used meta-analytic procedures in a review of the accuracy of the Mini-Mental State Examination in the detection of dementia and mild cognitive impairment.9 Thirty-four dementia studies and five mild cognitive impairment studies were included in the meta-analysis. It was concluded that the Mini-Mental State Examination offers modest accuracy with best value for ruling-out a diagnosis of dementia in community and primary care.

There have recently been advances in the methodology for undertaking systematic reviews of qualitative research, allowing us to have a more comprehensive understanding of clients’ experience in relation to a particular issue and to understand the acceptability of interventions to clients or the reasons why an intervention is not readily implemented. Some work has also been done to develop methods for combining results from both quantitative and qualitative research within a single review. However, discussion among researchers about how systematic reviews of qualitative research should best be conducted continues.10 There is still significant debate about whether a synthesis of qualitative studies is appropriate and whether it is acceptable to combine studies that use a variety of different methods.11

An interesting example of a review that combines qualitative and quantitative methods can be seen in a systematic review that examined older people’s views, perceptions and experiences of falls prevention interventions.12 The authors of the review searched eight databases using a broad search strategy in order to locate relevant qualitative and quantitative studies. The systematic review contained 24 studies, which consisted of 10 qualitative studies, one systematic review, three narrative reviews, three randomised controlled trials, three before/after studies and four cross-sectional observational studies. Synthesis of the quantitative studies in this review identified factors that encouraged older people’s participation in falls prevention interventions, while the findings from the 10 qualitative studies demonstrated the importance of considering older people’s views about falls interventions to ensure that these interventions are properly targeted.

Locating systematic reviews

It has been mentioned a number of times already in this book that a significant difficulty in locating research evidence is the overwhelming quantity of information that is available and the diverse range of journals in which information is published. Unfortunately, systematic reviews are not immune to this problem. As you saw in Chapter 3, the premier source for systematic reviews is the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. These reviews are written by volunteer researchers who work with one of many review groups that are coordinated by The Cochrane Collaboration (www.cochrane.org). Each review group has an editorial team which oversees the preparation and maintenance of the reviews, as well as the application of rigorous quality standards. This is why Cochrane reviews are so highly regarded. Those of you who are particularly interested in methodology issues may like to know that The Cochrane Collaboration has Method Groups who continue to refine methods for various types of reviews such as ones about effectiveness, diagnostic tests and prognostic information, as well as methods for qualitative reviews.

Another source of reliable information contained within the Cochrane Library is the Database of Abstracts of Reviews (DARE). It contains abstracts of systematic reviews that have been quality assessed. Each abstract includes a summary of the review together with a critical commentary about the overall quality. Chapter 3 provided the details of other resources that can be used to locate systematic reviews. These include the Joanna Briggs Institute, PEDro, OTseeker, PsycBITE, speechBITE and the large biomedical databases such as CINAHL and MEDLINE/PubMed (the latter contains a search strategy specifically for locating systematic reviews on the PubMed Clinical Queries screen).

How are systematic reviews conducted?

We believe that it is easier to learn how to appraise a systematic review if you first have an understanding of what is involved in performing a systematic review. Undertaking a systematic review requires a significant time commitment, with estimates varying depending on the number of citations/abstracts involved. Obviously, for some topics there is very little research that has been done whereas, for other topics, there is a huge amount of research to find and sort through. To give you an idea, one estimation is that it takes approximately 1139 hours or the equivalent of 6 months full-time work to complete a systematic review.13

We will now explain the basic steps involved in undertaking a systematic review, which are:

Plan and define the research question for a systematic review

As with any research study, when conducting a systematic review, the first place to start is planning the overall project. Planning also ensures that all aspects important to the scientific rigour of a review are undertaken to reduce the risk of bias. Each stage of the review needs to be thoroughly understood prior to moving on to plan the next stage. The question needs to be clearly focussed as too broad a question will not produce a useful review. The question should also make sense clinically. Involving consumers, at both the health professional and client level, may also be helpful when developing a plan, as this will ensure that areas of concern such as interventions or outcomes that might not otherwise be considered are addressed.14 Planning a review also requires decisions to be made about the methods for searching, screening, appraisal and synthesis. These decisions should be made before commencing the review itself as this will help to make the whole process systematic and more transparent for all involved.

Determine the types of studies to be included in the review

Review authors must decide: 1) which studies to include in the review; 2) how to locate the studies to include in the review; 3) how to assess the quality of the studies included; and 4) what data to extract from the studies. The type of studies to include will depend on the type of review question (for example, whether the review is about effects of intervention or about diagnostic tests). Within each type of review question there is then a further choice about study methods to include. Traditionally, inclusion criteria for systematic reviews about the effects of interventions, for instance, have focussed on including randomised controlled trials or quasi-randomised controlled trials. However, the frequency of inclusion of non-randomised studies and qualitative studies in effectiveness reviews may increase as methods for their synthesis become further developed.

Search for potentially eligible studies

The search methodology needs to be developed prior to commencing the review and to be clearly explained and reproducible. All components of the question of the review (such as the participants, interventions, comparisons and outcomes) need to be considered when developing the search strategy of the review. Each of the synonyms for each of the components also needs to be included in the search.15 The search strategy should be planned to include both English and non-English publications where possible and no date exclusions should be used. Searching should occur across multiple databases as it has been found that search strategies that are limited to one database do not identify all of the relevant studies.15 The review authors should also contact authors in the field in an attempt to locate other studies that have not already been identified and ongoing or planned studies in the area, and to ask about and obtain written copies of unpublished studies.16 The reason for doing this is to limit a problem called ‘publication bias’ that was explained earlier in the chapter and can occur due to study authors being more likely to submit studies with statistically significant results and journals being more likely to publish studies with positive results than those with negative outcomes.

As an illustration of how important it is that review authors use a comprehensive search strategy, one study found that 35% of all appropriate randomised controlled trials were not located by computerised searching17 and another reported that 10% of suitable trials for systematic reviews were missed when only electronic searching was conducted.18 Hand searching journals has been identified as vitally important to conducting a high quality systematic review19 as not all journals are indexed in electronic databases or may be missed by the search strategy used. It is highly recommended20 that authors of systematic reviews perform hand searching of the major journals that publish in the area relevant to the review question to increase the comprehensiveness of their search strategy. Citation tracking or use of the references from the studies found may help the reviewer to locate further studies on the topic and increase comprehensiveness of the search. Attempts should also be made to obtain unpublished studies (including masters and doctoral research and conference presentations) by searching the CENTRAL database in the Cochrane library and other trial registries.

Apply eligibility criteria to select studies

Once the search has been completed and potentially relevant studies identified, the next task is to decide which of the studies should be included in the systematic review. Not all articles that are located during the search will be directly relevant to the review question. Eligibility criteria are established to guide the selection of studies to be included in the review. The criteria specify the type of research methodologies that are to be included, the population and outcomes of interest and the interventions that will be considered. The selection process should then be carried out by two or more authors independently to minimise bias. Titles and abstracts are screened for relevance and eligibility. The full text of potentially relevant studies is retrieved so that a more detailed evaluation can be done. Studies that are not eligible (and this decision can be made on the basis of title and abstract information) are excluded at this point. A final evaluation by at least two authors is conducted on the full text articles and a decision is made whether to include or exclude the studies. If the review authors are conducting a Cochrane systematic review, studies that are excluded at this stage of the review process are listed in the review along with the reason why they were excluded.20

Assess the risk of bias in individual studies

The next step is to evaluate the quality of the studies that have been included in the review. Assessing the quality of the individual studies is vital to conducting a quality systematic review. Including poor quality trials would raise doubts about the reliability of the systematic review’s results and conclusions.21 To guard against errors and increase the reliability of the quality assessment, it is recommended that two or more review authors independently assess the quality of the included studies.20 Determining the potential for bias in individual studies can be done in a number of different ways, such as using the approach to appraising randomised controlled trials that was explained in Chapter 4 of this book. From the beginning of 2008, systematic reviews that are carried out through The Cochrane Collaboration have to use the ‘Risk of Bias’ tool.22 The risk of bias tool includes six different domains which are shown in Table 12.1, along with a definition of each of these criteria. Implementation of this tool requires two steps: 1) extracting information from the original study report about each criterion (see description column in Table 12.1); and then 2) making a judgement about the likely risk of bias in relation to each criterion (scored as ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’) (see Review authors’ judgement column in Table 12.1).

TABLE 12.1 The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in individual studies 22

| Domain | Description | Review authors’ judgement |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence generation | Describe the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups. | Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? |

| Allocation concealment | Describe the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to determine whether intervention allocations could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment. | Was allocation adequately concealed? |

| Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors Assessments should be made for each main outcome (or class of outcomes) | Describe all measures used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. Provide any information relating to whether the intended blinding was effective. | Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study? |

| Incomplete outcome data Assessments should be made for each main outcome (or class of outcomes) | Describe the completeness of outcome data for each main outcome, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. State whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers in each intervention group (compared with total randomised participants), reasons for attrition/exclusions where reported and any re-inclusions in analyses performed by the review authors. | Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? |

| Selective outcome reporting | State how the possibility of selective outcome reporting was examined by the review authors and what was found. | Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? |

| Other sources of bias | State any important concerns about bias not addressed in the other domains in the tool. | Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias? |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree