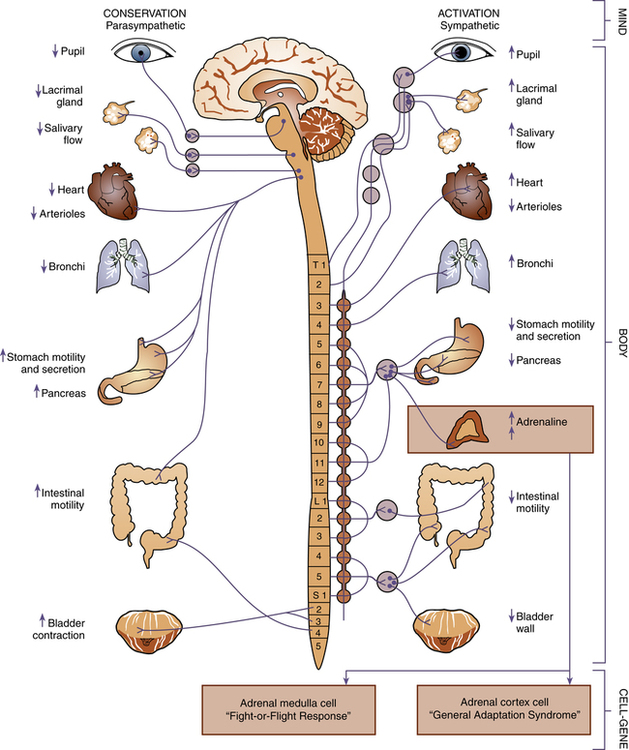

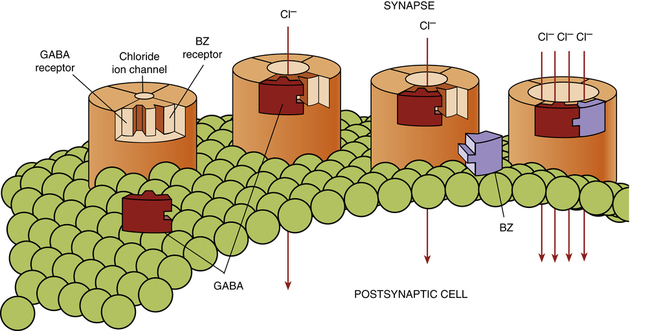

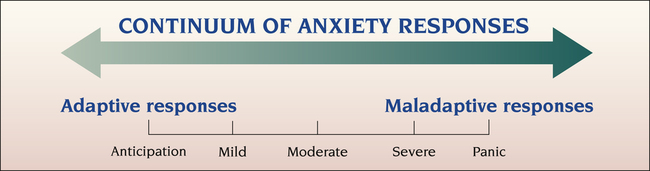

1. Describe the continuum of adaptive and maladaptive anxiety responses. 2. Identify behaviors associated with anxiety responses. 3. Analyze predisposing factors, precipitating stressors, and appraisal of stressors related to anxiety responses. 4. Describe coping resources and coping mechanisms related to anxiety responses. 5. Formulate nursing diagnoses related to anxiety responses. 6. Examine the relationship between nursing diagnoses and medical diagnoses related to anxiety responses. 7. Identify expected outcomes and short-term nursing goals related to anxiety responses. 8. Develop a patient education plan to promote the relaxation response. 9. Analyze nursing interventions related to anxiety responses. Anxiety is a part of everyday life. It has always existed and belongs to no particular era or culture. Anxiety involves one’s body, perceptions of self, and relationships with others, making it a basic concept in the study of psychiatric nursing and human behavior. It has been estimated that only about one fourth of those with anxiety disorders receive treatment (Giacobbe et al, 2008). However, these people are high users of health care services because they seek treatment for the various symptoms caused by anxiety, such as chest pain, palpitations, dizziness, and shortness of breath. such as entering school, starting a new job, or giving birth to a child. This characteristic of anxiety differentiates it from fear. Anxiety is about self-preservation. It occurs as a result of a threat to a person’s selfhood, self-esteem, or identity. It results from a threat to something that is central to one’s personality and essential to one’s existence and security. It may be connected with fear of punishment, disapproval, withdrawal of love, disruption of a relationship, isolation, or loss of body functioning. Culture is related to anxiety, because culture can influence the values one considers most important (Gwynn et al, 2008; Westermeyer et al, 2010). Peplau (1963) identified four levels of anxiety and described their effects: 1. Mild anxiety occurs with the tension of day-to-day living. During this stage the person is alert and the perceptual field is increased. The person sees, hears, and grasps more than before. This kind of anxiety can motivate learning and produce growth and creativity. 2. Moderate anxiety, in which the person focuses only on immediate concerns, involves narrowing of the perceptual field. The person sees, hears, and grasps less. The person blocks selected areas but can attend to more if directed to do so. 3. Severe anxiety is marked by a significant reduction in the perceptual field. The person tends to focus on a specific detail and not think about anything else. All behavior is aimed at relieving anxiety, and much direction is needed to focus on another area. 4. Panic is associated with dread and terror, as the person experiencing panic is unable to do things even with direction. Increased motor activity, decreased ability to relate to others, distorted perceptions, and loss of rational thought are all symptoms of panic. The panicked person is unable to communicate or function effectively. This level of anxiety cannot persist indefinitely, because it is incompatible with life. A prolonged period of panic would result in exhaustion and death. But panic can be treated safely and effectively. The nurse needs to be able to identify which level of anxiety a patient is experiencing by the behaviors observed. Figure 15-1 shows the range of anxiety responses from the most adaptive response of anticipation to the most maladaptive response of panic. The patient’s level of anxiety and its position on the continuum of coping responses are relevant to the nursing diagnosis and influence the type of intervention the nurse implements. In describing the effects of anxiety on physiological responses, mild and moderate anxiety levels heighten a person’s capacities. In contrast, severe anxiety and panic paralyze or overwork capacities. The physiological responses associated with anxiety are modulated primarily by the brain through the autonomic nervous system (Figure 15-2). The body adjusts internally without a conscious or voluntary effort. There are two types of autonomic responses: The sympathetic reaction occurs most often in anxiety responses. This reaction prepares the body to deal with an emergency situation by a fight-or-flight reaction. It also can trigger the general adaptation syndrome (Chapter 16). When the cortex of the brain perceives a threat, it sends a stimulus down the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system to the adrenal glands. Because of a release of epinephrine, respiration deepens, the heart beats more rapidly, and arterial pressure rises. Blood is shifted away from the stomach and intestines to the heart, central nervous system, and muscles. Glycogenolysis is accelerated, and the blood glucose level rises. For a few people the parasympathetic reaction may coexist or dominate and produce opposite effects. Other physiological reactions also may be evident. The variety of physiological responses to anxiety that the nurse may observe in patients is summarized in Box 15-1. Behavioral responses of the anxious patient have both personal and interpersonal aspects. High levels of anxiety affect coordination, involuntary movements, and responsiveness and also can disrupt human relationships. The anxious patient typically withdraws and decreases interpersonal involvement. The possible behavioral responses the nurse might observe are presented in Box 15-1. Mental or intellectual functioning also is affected by anxiety, resulting in problems concentrating, confusion, and poor problem solving. Cognitive responses the patient might display when experiencing anxiety are described in Box 15-1. Finally, the nurse can assess a patient’s emotional reactions, or affective responses, to anxiety by the subjective description of the patient’s personal experience. Often, patients describe themselves as tense, jittery, on edge, jumpy, worried, or restless. One patient described feelings in the following way: “I’m expecting something terribly bad to happen, but I don’t know what. I’m afraid, but I don’t know why. I guess you can call it a generalized bad feeling.” All these phrases are expressions of apprehension and overalertness. It seems clear that the person interprets anxiety as a kind of warning sign. Additional affective responses are listed in Box 15-1. • GABA system. The regulation of anxiety is related to the activity of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which controls the activity, or firing rates, of neurons in the parts of the brain responsible for producing anxiety. GABA is the most common inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. • When it crosses the synapse and attaches or binds to the GABA receptor on the postsynaptic membrane, the receptor channel opens, allowing for the exchange of ions. This exchange results in an inhibition or reduction of cell excitability and thus a slowing of cell activity. The theory is that people who have an excess of anxiety have a problem with the efficiency of this neurotransmission process. • When a person with anxiety takes a benzodiazepine (BZ) medication, which is from the antianxiety class of drugs, it binds to a place on the GABA receptor next to GABA. This makes the postsynaptic receptor more sensitive to the effects of GABA, enhancing neurotransmission and causing even more inhibition of cell activity (Figure 15-3). • The effect of GABA and BZ at the GABA receptor in various parts of the brain is a reduced firing rate of cells in areas implicated in anxiety disorders. The clinical result is that the person becomes less anxious. • The areas of the brain where GABA receptors are coupled to BZ receptors include the amygdala and hippocampus, both structures of the limbic system, which functions as the center of emotions (e.g., rage, arousal, fear) and memory. Patients with anxiety disorders may have a decreased antianxiety capacity of the GABA receptors in areas of the limbic system, making them more sensitive to anxiety and panic. • Norepinephrine system. The norepinephrine (NE) system is thought to mediate the fight-or-flight response. The part of the brain that manufactures NE is the locus ceruleus. It is connected by neurotransmitter pathways to other structures of the brain associated with anxiety, such as the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the cerebral cortex (the thinking, interpreting, and planning part of the brain). • Medications that decrease the activity of the locus ceruleus (antidepressants such as the tricyclics) effectively treat some anxiety disorders. This suggests that anxiety may be caused in part by an inappropriate activation of the NE system in the locus ceruleus and an imbalance between NE and other neurotransmitter systems. • Serotonin system. A dysregulation of serotonin (5-HT) neurotransmission may play a role in the etiology of anxiety, because patients experiencing these disorders may have hypersensitive 5-HT receptors. • Drugs that regulate serotonin, such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have been shown to be particularly effective in treating several of the anxiety disorders, suggesting a major role for 5-HT and its balance with other neurotransmitter systems in the etiology of anxiety disorders. Studies also suggest an excess of inflammatory actions of the immune system in individuals with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). High levels of inflammatory cytokines have been linked to PTSD vulnerability in traumatized individuals. The excessive inflammation may result from insufficient regulation by cortisol (Gill et al, 2009). A person’s general health has a great effect on predisposition to anxiety. Anxiety may accompany some physical disorders, such as those listed in Box 15-2. Coping mechanisms also may be impaired by toxic influences, dietary deficiencies, reduced blood supply, hormonal changes, and other physical causes (Strine et al, 2008). In addition, symptoms from some physical disorders may mimic or exacerbate anxiety. Perhaps the most important psychological trait is resilience to stress. Resilience is the ability to maintain normal functioning despite adversity. Resilience is associated with a number of protective psychosocial factors, including active coping style, positive outlook, interpersonal relatedness, moral compass, social support, role models, and cognitive flexibility. Resilience is discussed in Chapter 12. Having purpose in life and undertaking and mastering difficult tasks are effective ways to increase one’s resilience to stress (Alim et al, 2008). For example, men and women who successfully managed stressful situations in childhood, such as death or illness of a parent or sibling, family relocation, or loss of friendship, are more resistant to adult stressors, such as divorce, death, major illness, or job loss. However individuals who experienced extreme childhood stress that they could not control or master, such as physical or sexual abuse, may be more vulnerable to future stressors. 1. Approach-approach, in which the person wants to pursue two equally desirable but incompatible goals. An example is having two very attractive job offers. This type of conflict seldom produces anxiety. 2. Approach-avoidance, in which the person wishes to both pursue and avoid the same goal. The patient who wants to express anger but feels great anxiety and fear in doing so experiences this type of conflict. Another example is the ambitious business executive who must compromise values of honesty and loyalty to be promoted. 3. Avoidance-avoidance, in which the person must choose between two undesirable goals. Because neither alternative seems beneficial, this is a difficult choice that is usually accompanied by much anxiety. An example is when a person observes a friend cheating and feels the need to report the act but worries about the loss of friends that might result from reporting the violation. 4. Double approach-avoidance, in which the person can see both desirable and undesirable aspects of both alternatives. An example is the conflict experienced by a person living with the pain of an unsatisfying social and emotional life. The alternative is to seek psychiatric help and expose oneself to the threat and potential pain of the therapy process. Double approach-avoidance conflict feelings often are described as ambivalence. Experiencing or witnessing trauma has been associated with a variety of anxiety disorders, particularly posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Most traumatized individuals experience more than one trauma in their lifetime, and the risk of PTSD increases with each event (Nayback, 2009; Doctor et al, 2011). The majority of individuals involved in traumatic events will not develop a psychological disorder. Only 5% to 10% of those who experience trauma develop PTSD (Snyder, 2008). The so-called “normal” response is highly variable. Some people develop a marked initial reaction that resolves over a few weeks. Others have little or no initial reaction and do not develop any difficulties. However, a minority develop mental health problems that require intervention. With the return of soldiers serving in wars and the increasing violence in society, PTSD is becoming a more prevalent and impairing condition (Ray, 2008). Specifically, the negative effects of combat are deep and enduring, and veterans with combat stress reaction may be six times more likely to develop PTSD. PTSD in veterans is discussed in Chapter 39. An individual at risk for PTSD should be screened using the primary care tool presented in Box 15-3. It focuses on the core PTSD symptom clusters. Anyone answering “yes” to three of the four items should have a more formal assessment. Maturational and situational crises, as described in Chapter 13, also can precipitate a maladaptive anxiety response (Ameratunga et al, 2009). In total, precipitating stressors can be grouped into two categories: threats to physical integrity and threats to self-system. As anxiety increases to the severe and panic levels, the behaviors displayed by a person become more intense and potentially injurious, and quality of life decreases. People seek to avoid anxiety and the circumstances that produce it. When experiencing anxiety, people use various coping mechanisms to try to relieve it (Box 15-4). The inability to cope with anxiety constructively is a primary cause of psychological problems. crying, sleeping, eating, yawning, laughing, cursing, physical exercise, and daydreaming. Oral behavior, such as smoking and drinking, is another way of coping with mild anxiety. As coping mechanisms, they have certain drawbacks. First, ego defense mechanisms operate on unconscious levels. The person has little awareness of what is happening and little control over events. Secondly, they involve a degree of self-deception and reality distortion. Therefore they usually do not help the person cope with the problem realistically. Table 15-1 lists some of the more common ego defense mechanisms and examples of each. TABLE 15-1

Anxiety Responses and Anxiety Disorders

Continuum of Anxiety Responses

Defining Characteristics

Levels of Anxiety

Assessment

Behaviors

Predisposing Factors

Biological

Psychological

Behavioral

Precipitating Stressors

Coping Mechanisms

Emotion- or Ego-Focused Coping

DEFENSE MECHANISM

EXAMPLE

Compensation: Process by which people make up for a perceived weakness by strongly emphasizing a feature that they consider more desirable.

A businessman perceives his small physical stature negatively. He tries to overcome this by being aggressive, forceful, and controlling in business dealings.

Denial: Avoidance of disagreeable realities by ignoring or refusing to recognize them; the simplest and most primitive of all defense mechanisms.

Ms. P has just been told that her breast biopsy indicates a malignancy. When her husband visits her that evening, she tells him that no one has discussed the laboratory results with her.

Displacement: Shift of emotion from a person or object to another, usually neutral or less dangerous, person or object.

A 4-year-old boy is angry because he has just been punished by his mother for drawing on his bedroom walls. He begins to play war with his soldier toys and has them fight with each other.

Dissociation: The separation of a group of mental or behavioral processes from the rest of the person’s consciousness or identity.

A man is brought to the emergency room by the police and is unable to explain who he is and where he lives or works.

Identification: Process by which people try to become like someone they admire by taking on thoughts, mannerisms, or tastes of that person.

Sally, 15 years old, has her hair styled like that of her young English teacher, whom she admires.

Intellectualization: Excessive reasoning or logic is used to avoid experiencing disturbing feelings.

A woman avoids dealing with her anxiety in shopping malls by explaining that shopping is a frivolous waste of time and money.

Introjection: Intense identification in which people incorporate qualities or values of another person or group into their own ego structure. It is one of the earliest mechanisms of the child, important in formation of conscience.

Eight-year-old Jimmy tells his 3-year-old sister, “Don’t scribble in your book of nursery rhymes. Just look at the pretty pictures,” thus expressing his parents’ values.

Isolation: Splitting off of emotional components of a thought, which may be temporary or long term.

A medical student dissects a cadaver for her anatomy course without being disturbed by thoughts of death.

Projection: Attributing one’s thoughts or impulses to another person. Through this process one can attribute intolerable wishes, emotional feelings, or motivation to another person.

A young woman who denies she has sexual feelings about a co-worker accuses him without basis of trying to seduce her.

Rationalization: Offering a socially acceptable or apparently logical explanation to justify or make acceptable otherwise unacceptable impulses, feelings, behaviors, and motives.

John fails an examination and complains that the lectures were not well organized or clearly presented.

Reaction formation: Development of conscious attitudes and behavior patterns that are opposite to what one really feels or would like to do.

A married woman who feels attracted to one of her husband’s friends treats him rudely.

Regression: Retreat to behavior characteristic of an earlier level of development.

Four-year-old Nicole, who has been toilet trained for more than 1 year, begins to wet her pants again when her new baby brother is brought home from the hospital.

Repression: Involuntary exclusion of a painful or conflicted thought, impulse, or memory from awareness. It is the primary ego defense, and other mechanisms tend to reinforce it.

Mr. R does not recall hitting his wife when she was pregnant.

Splitting: Viewing people and situations as either all good or all bad; failure to integrate the positive and negative qualities of oneself.

A friend tells you that you are the most wonderful person in the world one day and how much she hates you the next day.

Sublimation: Acceptance of a socially approved substitute goal for a drive whose normal channel of expression is blocked.

Ed has an impulsive and physically aggressive nature. He tries out for the football team and becomes a star tackle.

Suppression: A process often listed as a defense mechanism, but really it is a conscious counterpart of repression. It is intentional exclusion of material from consciousness. At times, it may lead to repression.

A young man at work finds he is thinking so much about his date that evening that it is interfering with his work. He decides to put it out of his mind until he leaves the office for the day.

Undoing: Act or communication that partially negates a previous one; a primitive defense mechanism.

Larry makes a passionate declaration of love to Sue on a date. At their next meeting he treats her formally and distantly. ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Anxiety Responses and Anxiety Disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access