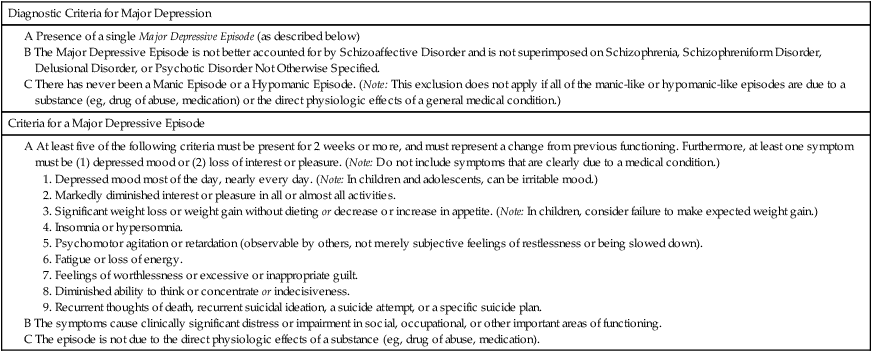

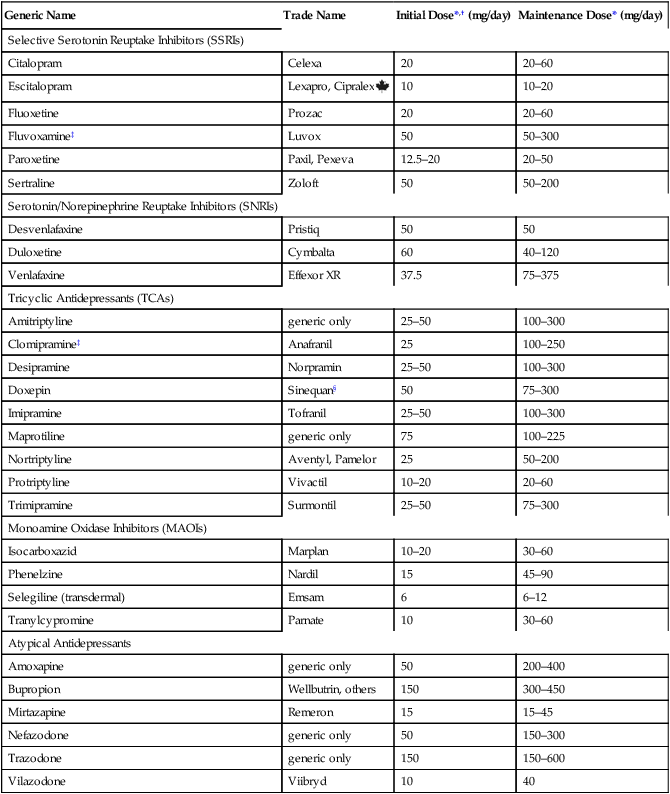

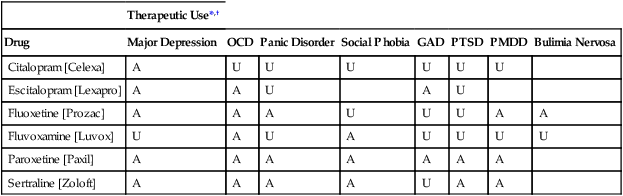

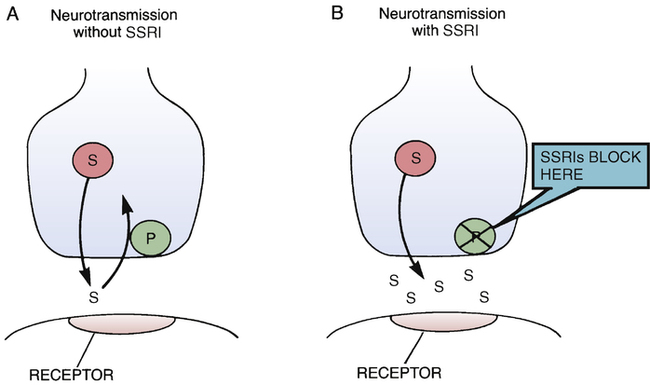

CHAPTER 32 Diagnostic criteria for a major depression are summarized in Table 32–1. As indicated, the principal symptoms are depressed mood and loss of pleasure or interest in all or nearly all of one’s usual activities and pastimes. Associated symptoms include insomnia (or sometimes hypersomnia); anorexia and weight loss (or sometimes hyperphagia and weight gain); mental slowing and loss of concentration; feelings of guilt, worthlessness, and helplessness; thoughts of death and suicide; and overt suicidal behavior. For a diagnosis to be made, symptoms must be present most of the day, nearly every day, for at least 2 weeks. TABLE 32–1 DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Major Depression Modified from the proposed diagnostic criteria for Major Depression and a Major Depressive Episode, to be published in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Expected publication date: May 2013. Copyright © American Psychiatric Association. The proposed criteria are from the DSM-5 web site—www.DSM5.org—accessed on November 11, 2011. The etiology of major depression is complex and incompletely understood. For some individuals, depression seems to descend “out of the blue”; otherwise healthy people—unexpectedly and without apparent cause—find themselves feeling profoundly depressed. For many others, depressive episodes are brought on by stressful life events, such as bereavement, loss of a job, or childbirth (Box 32–1). Since depression does not occur in everyone, it would appear that some people are more vulnerable than others. Factors that may contribute to vulnerability include genetic heritage, a difficult childhood, and chronic low self-esteem. Available antidepressants are listed in Table 32–2. As indicated, these drugs fall into five major classes: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and atypical antidepressants. All of these classes are equally effective, as are the individual drugs within each class. Hence, differences among these drugs relate mainly to side effects and drug interactions. TABLE 32–2 Antidepressant Classes and Adult Dosages *Doses listed are total daily doses. Depending on the drug and the patient, the total dose may be given in a single dose or in divided doses. †Initial doses are employed for 4 to 8 weeks, the time required for most symptoms to respond. Dosage is gradually increased as required. ‡Fluvoxamine and clomipramine are not approved for major depression. §Doxepin is also available in a low-dose formulation, sold as Silenor, for treating insomnia. • For a patient with fatigue, choose a drug that causes CNS stimulation (eg, fluoxetine, bupropion). • For a patient with insomnia, choose a drug that causes substantial sedation (eg, mirtazapine). • For a patient with sexual dysfunction, choose bupropion, a drug that enhances libido. • For a patient with chronic pain, choose duloxetine or a TCA, drugs that can relieve chronic pain. Once a drug has been selected for initial treatment, it should be used for 4 to 8 weeks to assess efficacy. As a rule, dosage should be low initially (to reduce side effects), and then gradually increased (see Table 32–2). If the initial drug is not effective, we have four major options. Specifically, we can: • Switch to another drug in the same class • Switch to another drug in a different class • Add a second drug, such as lithium, thyroid hormone, or an atypical antidepressant The SSRIs were introduced in 1987 and have since become our most commonly prescribed antidepressants, accounting for over $3 billion in annual sales. These drugs are indicated for major depression as well as several other psychologic disorders (Table 32–3). Characteristic side effects are nausea, agitation/insomnia, and sexual dysfunction (especially anorgasmia). The SSRIs can interact adversely with MAOIs and other serotonergic drugs, and hence these combinations must be avoided. In addition, when used late in pregnancy, SSRIs can lead to a withdrawal syndrome and persistent pulmonary hypertension in the infant. Like all other antidepressants, SSRIs may increase the risk of suicide. Compared with the TCAs and MAOIs, SSRIs are equally effective, better tolerated, and much safer. Death by overdose is extremely rare. TABLE 32–3 Therapeutic Uses of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors *A = approved use, U = unlabeled use. †GAD = generalized anxiety disorder, OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder, PMDD = premenstrual dysphoric disorder, PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder. The mechanism of action of fluoxetine and the other SSRIs is depicted in Figure 32–1. As shown, SSRIs selectively block neuronal reuptake of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, or 5-HT), a monoamine neurotransmitter. As a result of reuptake blockade, the concentration of 5-HT in the synapse increases, causing increased activation of postsynaptic 5-HT receptors. This mechanism is consistent with the theory that depression stems from a deficiency in monoamine-mediated transmission—and hence should be relieved by drugs that can intensify monoamine effects. Fluoxetine is used primarily for major depression. In addition, the drug is approved for bipolar disorder (see Chapter 33), obsessive-compulsive disorder (see Chapter 35), panic disorder (see Chapter 35), bulimia nervosa, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (see Chapter 61). Unlabeled uses include post-traumatic stress disorder, social phobia, alcoholism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, migraine, Tourette’s syndrome, and obesity. By increasing serotonergic transmission in the brainstem and spinal cord, fluoxetine and other SSRIs can cause serotonin syndrome. This syndrome usually begins 2 to 72 hours after treatment onset. Signs and symptoms include altered mental status (agitation, confusion, disorientation, anxiety, hallucinations, poor concentration) as well as incoordination, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, excessive sweating, tremor, and fever. Deaths have occurred. The syndrome resolves spontaneously after discontinuing the drug. The risk of serotonin syndrome is increased by concurrent use of MAOIs and other drugs (see below under Drug Interactions). Other drugs that increase the risk of serotonin syndrome include the serotonergic drugs listed in Table 32–4, drugs that inhibit CYP2D6 (and thereby raise fluoxetine levels), tramadol (an analgesic), and linezolid (an antibiotic that inhibits MAO). TABLE 32–4 Drugs That Promote Activation of Serotonin Receptors In addition to fluoxetine, five other SSRIs are available: citalopram [Celexa], escitalopram [Lexapro, Cipralex

Antidepressants

Major depression: clinical features, pathogenesis, and treatment overview

Clinical features

Pathogenesis

Drugs used for depression

Generic Name

Trade Name

Initial Dose*,† (mg/day)

Maintenance Dose* (mg/day)

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

Citalopram

Celexa

20

20–60

Escitalopram

Lexapro, Cipralex ![]()

10

10–20

Fluoxetine

Prozac

20

20–60

Fluvoxamine‡

Luvox

50

50–300

Paroxetine

Paxil, Pexeva

12.5–20

20–50

Sertraline

Zoloft

50

50–200

Serotonin/Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs)

Desvenlafaxine

Pristiq

50

50

Duloxetine

Cymbalta

60

40–120

Venlafaxine

Effexor XR

37.5

75–375

Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs)

Amitriptyline

generic only

25–50

100–300

Clomipramine‡

Anafranil

25

100–250

Desipramine

Norpramin

25–50

100–300

Doxepin

Sinequan§

50

75–300

Imipramine

Tofranil

25–50

100–300

Maprotiline

generic only

75

100–225

Nortriptyline

Aventyl, Pamelor

25

50–200

Protriptyline

Vivactil

10–20

20–60

Trimipramine

Surmontil

25–50

75–300

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

Isocarboxazid

Marplan

10–20

30–60

Phenelzine

Nardil

15

45–90

Selegiline (transdermal)

Emsam

6

6–12

Tranylcypromine

Parnate

10

30–60

Atypical Antidepressants

Amoxapine

generic only

50

200–400

Bupropion

Wellbutrin, others

150

300–450

Mirtazapine

Remeron

15

15–45

Nefazodone

generic only

50

150–300

Trazodone

generic only

150

150–600

Vilazodone

Viibryd

10

40

Basic considerations

Drug selection

Managing treatment

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

Therapeutic Use*,†

Drug

Major Depression

OCD

Panic Disorder

Social Phobia

GAD

PTSD

PMDD

Bulimia Nervosa

Citalopram [Celexa]

A

U

U

U

U

U

U

Escitalopram [Lexapro]

A

A

U

A

U

Fluoxetine [Prozac]

A

A

A

U

U

U

A

A

Fluvoxamine [Luvox]

U

A

U

A

U

U

U

U

Paroxetine [Paxil]

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

Sertraline [Zoloft]

A

A

A

A

U

A

A

Fluoxetine

Mechanism of action

Mechanism of action of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Mechanism of action of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

A, Under drug-free conditions, the actions of serotonin are terminated by active uptake of the transmitter back into the nerve terminals from which it was released. B, By inhibiting the reuptake pump for serotonin, the SSRIs cause the transmitter to accumulate in the synaptic space, thereby intensifying transmission. (P = uptake pump, S = serotonin, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.)

Therapeutic uses

Adverse effects

Serotonin syndrome.

Drug interactions

MAOIs and other drugs that increase the risk of serotonin syndrome.

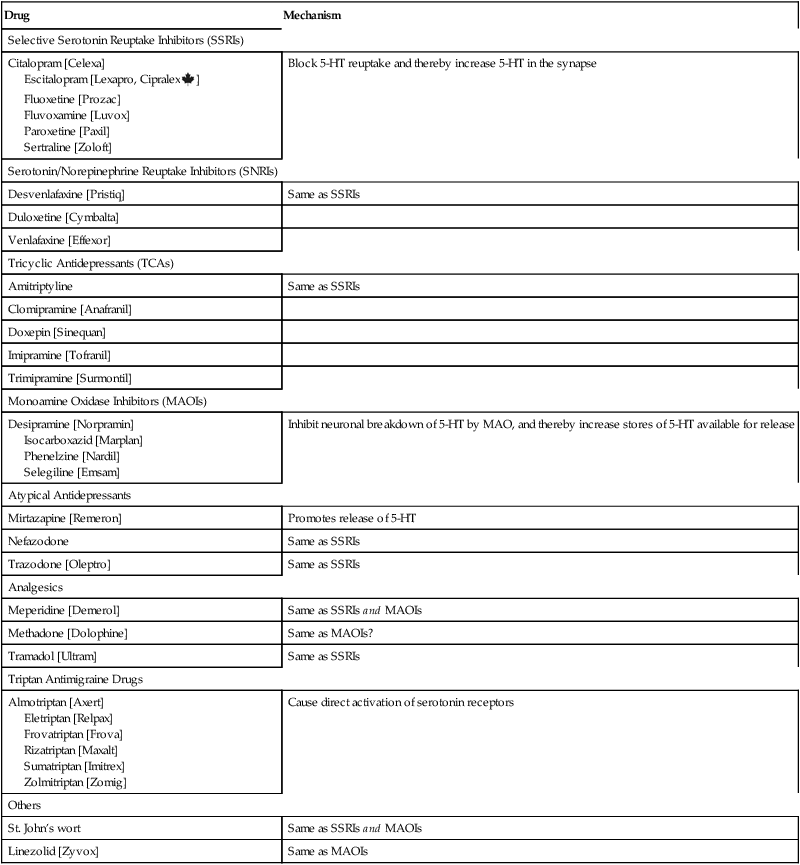

Drug

Mechanism

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

Citalopram [Celexa]

Escitalopram [Lexapro, Cipralex![]() ]

]

Fluoxetine [Prozac]

Fluvoxamine [Luvox]

Paroxetine [Paxil]

Sertraline [Zoloft]

Block 5-HT reuptake and thereby increase 5-HT in the synapse

Serotonin/Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs)

Desvenlafaxine [Pristiq]

Same as SSRIs

Duloxetine [Cymbalta]

Venlafaxine [Effexor]

Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs)

Amitriptyline

Same as SSRIs

Clomipramine [Anafranil]

Doxepin [Sinequan]

Imipramine [Tofranil]

Trimipramine [Surmontil]

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

Desipramine [Norpramin]

Isocarboxazid [Marplan]

Phenelzine [Nardil]

Selegiline [Emsam]

Inhibit neuronal breakdown of 5-HT by MAO, and thereby increase stores of 5-HT available for release

Atypical Antidepressants

Mirtazapine [Remeron]

Promotes release of 5-HT

Nefazodone

Same as SSRIs

Trazodone [Oleptro]

Same as SSRIs

Analgesics

Meperidine [Demerol]

Same as SSRIs and MAOIs

Methadone [Dolophine]

Same as MAOIs?

Tramadol [Ultram]

Same as SSRIs

Triptan Antimigraine Drugs

Almotriptan [Axert]

Eletriptan [Relpax]

Frovatriptan [Frova]

Rizatriptan [Maxalt]

Sumatriptan [Imitrex]

Zolmitriptan [Zomig]

Cause direct activation of serotonin receptors

Others

St. John’s wort

Same as SSRIs and MAOIs

Linezolid [Zyvox]

Same as MAOIs

Other SSRIs

![]() ], fluvoxamine [Luvox], paroxetine [Paxil, Pexeva], and sertraline [Zoloft]. All five are similar to fluoxetine. Antidepressant effects equal those of TCAs. Characteristic side effects are nausea, insomnia, headache, nervousness, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, hyponatremia, GI bleeding, and NAS and PPHN (in infants who were exposed to these drugs late in gestation). Serotonin syndrome is a potential complication with all SSRIs, especially if these agents are combined with MAOIs or other serotonergic drugs. The principal differences among the SSRIs relate to duration of action. Patients who experience intolerable adverse effects with one SSRI may find a different SSRI more acceptable. As with fluoxetine, withdrawal should be done slowly. In contrast to the TCAs, the SSRIs do not cause hypotension or anticholinergic effects, and, with the exception of fluvoxamine, do not cause sedation. When taken in overdose, these drugs do not cause cardiotoxicity. Therapeutic uses for individual SSRIs are summarized in Table 32–3.

], fluvoxamine [Luvox], paroxetine [Paxil, Pexeva], and sertraline [Zoloft]. All five are similar to fluoxetine. Antidepressant effects equal those of TCAs. Characteristic side effects are nausea, insomnia, headache, nervousness, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, hyponatremia, GI bleeding, and NAS and PPHN (in infants who were exposed to these drugs late in gestation). Serotonin syndrome is a potential complication with all SSRIs, especially if these agents are combined with MAOIs or other serotonergic drugs. The principal differences among the SSRIs relate to duration of action. Patients who experience intolerable adverse effects with one SSRI may find a different SSRI more acceptable. As with fluoxetine, withdrawal should be done slowly. In contrast to the TCAs, the SSRIs do not cause hypotension or anticholinergic effects, and, with the exception of fluvoxamine, do not cause sedation. When taken in overdose, these drugs do not cause cardiotoxicity. Therapeutic uses for individual SSRIs are summarized in Table 32–3.

Antidepressants

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access