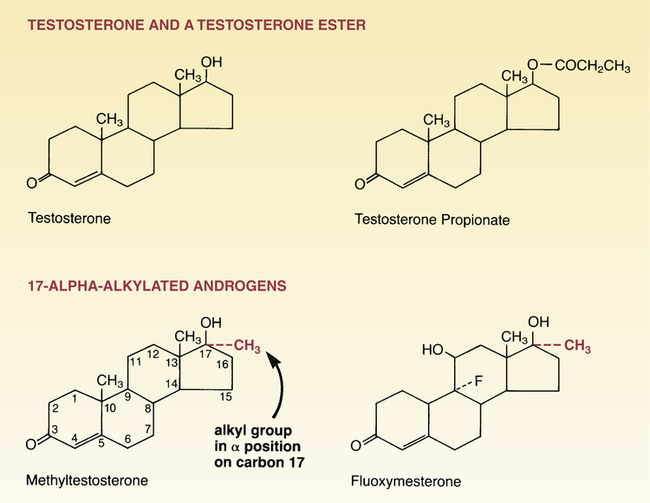

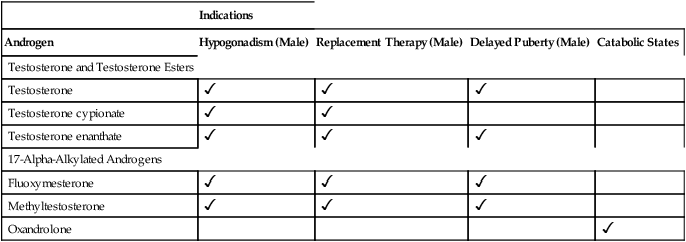

CHAPTER 65 Testosterone is the prototype of the androgen hormones. This compound is the principal endogenous androgen in both males and females. In addition to its physiologic role, testosterone is representative of the androgens employed clinically. The structural formula of testosterone is shown in Figure 65–1. The androgens used clinically fall into two basic groups: (1) testosterone and testosterone esters, and (2) 17-alpha-alkylated compounds (noted for their hepatotoxicity). Androgens belonging to each group are listed in Table 65–1. TABLE 65–1 Approved Uses of Individual Androgens Individual androgens differ in their applications. No single androgen is employed for all of the uses discussed below. Specific applications of individual androgens are summarized in Table 65–1. Androgen replacement therapy is beneficial when testicular failure occurs in adult males. Treatment restores libido, increases ejaculate volume, and supports expression of secondary sex characteristics. However, treatment will not restore fertility. The principal drugs employed for testosterone replacement are testosterone itself and two testosterone esters: testosterone enanthate and testosterone cypionate. Preparations and dosages for replacement therapy are summarized in Table 65–2 and discussed below under Androgen Preparations for Male Hypogonadism. Replacement therapy in older males is discussed further in Box 65–1.

Androgens

Testosterone

Structural formulas of representative androgens.

Structural formulas of representative androgens.

Clinical pharmacology of the androgens

Classification

Indications

Androgen

Hypogonadism (Male)

Replacement Therapy (Male)

Delayed Puberty (Male)

Catabolic States

Testosterone and Testosterone Esters

Testosterone

Testosterone cypionate

Testosterone enanthate

17-Alpha-Alkylated Androgens

Fluoxymesterone

Methyltestosterone

Oxandrolone

Therapeutic uses

Replacement therapy.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Androgens

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access