CHAPTER 25

Amputation

Cynthia Christensen

OBJECTIVES

1. Identify risk factors for amputation.

2. Identify early interventions to reduce the risk for amputation.

3. List postoperative interventions for decreasing secondary complications.

4. Describe the essential factors necessary for successful rehabilitation after amputation.

5. Describe the impact amputation has on a person’s life.

There are approximately 2 million Americans with some form of limb loss, more than 185,000 new amputations each year in the United States and more than 250,000 amputees worldwide in the United Nations registry (Ketz, 2008; Wehmer & Jones, 2014). Amputations can be described as primary (performed as an initial procedure) and secondary (performed after revascularization) (MacVittie, 1998).

I. Introduction

I. Introduction

A. Amputation should be performed at the level that allows for complete healing but will also permit the most efficient use of the limb.

1. Upper-extremity amputations account for 15% to 20% of all amputations (Krupski, 2000).

2. Lower-extremity amputations (LEA) comprise the majority of amputations and will be the focus of further discussion.

a. Approximately two thirds are below the knee (Fitzgerald, 2000; Fletcher et al., 2002).

b. Approximately 33% are above the knee (Fitzgerald, 2000).

B. About 30% to 60% of the LEA Occurs in Persons with Diabetes Mellitus (Amputation and Amputation Surgery, 2011; Complications of Diabetes in the US, 2011; Deery & Sangeorzan, 2001; Helt & Jacobsen, 1999; Munro, 2001; Wehmer & Jones, 2014).

C. The Incidence of LEA is Twice as High for Men as for Women (Carrington et al., 2001; Krapfl, Gohdes, & Burrows, 2003).

D. In the United States, African Americans have two to three times the risk for diabetes-related LEA compared with whites in the United States. This may be accounted for by inequalities in access to health care (Leggetter, Chaturvedi, Fuller, & Edmonds, 2002).

E. Native American’s (Krapfl et al., 2003) rate of LEA is 3.5 times higher than for non-Hispanic whites.

F. Eighty Percent of Americans Requiring LEA have Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) (Bryant, 2001) and may go through four stages of development:

1. Asymptomatic PAD

2. Claudication

3. Rest pain

4. Tissue necrosis

5. Most persons progress directly from stage 1 to stage 3 or 4 (Nehler, Hiatt, & Taylor, 2003)

G. It is Estimated that 5% of Persons with Intermittent Claudication will Progress to Critical Limb Ischemia and Amputation (Lawson, 2005).

H. Vascular Patients who have had one amputation have a 20% to 50% chance of a contralateral amputation in 1 to 3 years and a 39% to 68% mortality rate within 5 years (Datta, 2001; Deery & Sangeorzan, 2001; MacVittie, 1998). The survival rate is lower in persons with diabetes mellitus, especially with end-stage kidney disease or other comorbidities. The 1- and 5-year survival rates are 50% and 15%, respectively (Zgonis, Stapleton, Jeffries, Girard-Powell, & Foster, 2008).

I. Approximately 33% of persons with acute preoperative ischemia will require an amputation with mortality rates of 5% to 11% (Keshelava et al., 2009).

J. Absent Sensation on the sole of the foot has been related to a 10-fold risk of foot ulcer development and a 17-fold risk of amputation (Wehmer & Jones, 2014).

K. Persons with Diabetes Who have Recurrent Ulcers have a 5% to 15% Risk of Amputation (Amputation and Amputation Surgery, 2011).

II. Etiology/Precipitating Factors (see Table 25-1)

II. Etiology/Precipitating Factors (see Table 25-1)

Table 25-1 Etiology and Precipitating Factors for LEA

| Peripheral artery diseasea |

| Diabetic foot ulcerationa |

| Peripheral neuropathya |

| Trauma |

| Infection |

| Impaired wound healing |

| Limited joint mobility |

| Malignancy |

| Thermal injury |

| Congenital malformations |

| Cutaneous fungal infections |

| High glycosylated hemoglobin level |

| Contributing medical conditions causing neuropathy: 1. Thyroid disease 2. Spinal stenosis 3. Amyloidosis 4. Alcoholism 5. Vasculitis 6. Diabetes mellitus |

| Contributing medical conditions causing peripheral edema: 1. Congestive heart failure 2. Venous insufficiency 3. Congenital lymphedema 4. Hypothyroidism |

| Contributing medical conditions causing decreased peripheral perfusion: 1. Peripheral artery disease 2. Congestive heart failure 3. Buerger disease 4. Scleroderma |

| Medications that cause neuropathy: 1. Chemotherapy 2. Antiretrovirals |

| Medications that decrease arterial flow: 1. Beta-blockers 2. Alpha-agonists |

aMost common factors (Gibson, 2001).

Bryant (2001); Carrington et al. (2001); Deery & Sangeorzan (2001); Gibson (2001); Watts et al. (2001).

III. Assessment

III. Assessment

A. Risk Factors and Primary Prevention

1. Risk factors for LEA include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, past and present tobacco use, end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis, dyslipidemia, foot ulcer, heel crack, or plantar callous (Abou-Zamzam, Teruya, Killeen, & Ballard, 2003; Calle-Pascual et al., 2001; Carrington et al., 2001; Deery & Sangeorzan, 2001).

a. A severe diabetic foot infection has a 25% increased risk of major LE amputation (Zgonis, Stapleton, Girard-Powell, & Hagino, 2008).

b. Smokers are twice as likely as nonsmokers to develop critical limb ischemia leading to amputation (Muir, 2009).

c. Persons with peripheral artery disease and diabetes are more likely to develop impaired wound healing and neuropathy making them a higher risk for gangrene resulting in a higher rate of amputation (Muir, 2009).

2. Primary prevention includes reduction in the incidence of disease by eliminating or controlling risk factors. This includes:

a. Better control of dietary factors resulting in tighter control of hypertension, glycosylated hemoglobin levels and dyslipidemia; smoking cessation, exercise, and foot care (Lawson, 2005; Muir, 2009).

b. Comprehensive foot care programs that include risk assessment, foot care education and prevention, treatment of foot problems, and referrals to specialists can reduce amputation rates by 45% to 85% (Complications of diabetes in the US, 2011).

c. Ninety percent of diabetic foot ulcers will heal when treated with appropriate antibiotics, restoration of arterial perfusion, and aggressive wound care including off-loading of the ulcer (Deery & Sangeorzan, 2001).

B. Patient History

1. Subjective findings include:

a. Numbness, burning, itching, tingling, crawling, prickling

b. Pain burning or sharp; may be worse at night or with recumbent position. Persons with pain may sleep sitting in a chair for relief

c. Staining of socks or foot odor

d. Leg swelling with or without dependent position

e. History of previous foot ulceration, infection, or surgery

f. Claudication

g. Footwear usage in and outside the house

h. Report of tobacco usage (Deery & Sangeorzan, 2001; Gibson, 2001)

2. Objective findings include:

a. Impaired monofilament sensation

b. Impaired vibration perception

c. Absent Achilles tendon reflex

d. Callous foot deformities

e. Inappropriate footwear

f. Absent pedal pulses and/or decreased capillary refill

g. Presence of edema, infection, necrosis or gangrene (Deery & Sangeorzan, 2001; Muller et al., 2002; Spollett, 2006; Zgonis et al., 2008)

C. Physical Examination

1. Inspection

a. General inspection for loss of hair on the legs and feet; dry skin or venous stasis dermatitis; presence of foot deformities, such as small muscle wasting, hammer/claw toes, bony prominences, prominent metatarsal heads, Charcot arthropathy, and limited joint mobility

b. Inspect feet, including all toe web spaces for ulceration, excessive moisture leading to maceration, dryness predisposing skin to cracking and tearing, focal erythema as a sign of pressure, friction fracture, or infection.

c. Examine footwear for presence of foreign bodies, abnormal wear pattern, or internal staining suggesting an open wound. Bulging of shoes suggests poor fit while an irregular wear pattern can indicate biomechanical abnormalities (Carrington et al., 2001; Deery & Sangeorzan, 2001; Wehmer & Jones, 2014).

2. Palpation of legs and feet is done to assess for temperature changes, degree of pulses, and for capillary refill (Carrington et al., 2001; Deery & Sangeorzan, 2001; Muir, 2009; Wehmer & Jones, 2014)

D. Consideration Across the Life Span. Lower-extremity amputations performed as a result of injury, trauma, malignancy, battlefield wounds, or congenital malformations may occur at any age. Nontraumatic indications for LEA occur around the sixth decade of life with a dramatic increase in the eighth decade (Bryant, 2001; Calle-Pascual et al., 2001; Marks & Michael, 2001; Wehmer & Jones, 2014)

IV. Pertinent Diagnostic Testing. Testing is done not only to aid in wound healing, but to aid in the selection of the amputation site.

IV. Pertinent Diagnostic Testing. Testing is done not only to aid in wound healing, but to aid in the selection of the amputation site.

A. Noninvasive Tests Include:

1. Segmental Doppler systolic blood pressure measurements; toe pressure may be the most helpful, especially in the presence of arterial calcification

2. Laser Doppler velocimetry to evaluate blood flow

3. Skin perfusion pressure measured by:

a. Laser Doppler measurement

b. Photoelectric measurement

4. Thermographic measurement of skin temperature

5. Measurement of transcutaneous oxygen tension

6. Measurement of transcutaneous carbon dioxide tension

7. Common peroneal motor nerve conduction velocity

8. Vibration perception threshold

9. Traditional radiography

10. Pulse volume recordings (Bacharach, 2001; Carrington et al., 2001; Durham, 2000; Gibson, 2001; Muir, 2009; Nehler et al., 2003; Wehmer & Jones, 2014; Zgonis et al., 2008)

B. Invasive Test Include:

1. Fluorescein dye measurements

2. Isotope measurements of:

a. Skin perfusion pressures

b. Skin blood flow

3. Bone scan

4. 24-hour leukocyte scan

5. Angiography to determine possibility of limb salvage through revascularization

6. Computerized tomography (CT)

7. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

8. MRI with angiography (Bacharach, 2001; Durham, 2000, MacVittie, 1998; Muir, 2009; Wehmer & Jones, 2014; Zgonis et al., 2008)

C. Laboratory Tests Include:

1. Complete blood count with differential

2. Metabolic panel

3. Sedimentation rate

4. C-reactive protein (Wehmer & Jones, 2014; Zgonis et al., 2008)

V. Medical/Surgical Management. Revascularization for nontraumatic distal extremity disease is the first choice when applicable. Bypass to plantar arteries is not only feasible but may result in prolonged patency and limb salvage. Approximately 14% to 20% of persons with critical lower limb ischemia are not suited for reconstruction due to occluded crural and pedal arteries, which results in amputation (Keshelava et al., 2009; Roddy et al., 2001). Revascularization may be inappropriate in some cases such as in persons who are wheelchair bound, neurologically impaired, or have extremely limited life expectancy (Abou-Zamzam et al., 2003).

V. Medical/Surgical Management. Revascularization for nontraumatic distal extremity disease is the first choice when applicable. Bypass to plantar arteries is not only feasible but may result in prolonged patency and limb salvage. Approximately 14% to 20% of persons with critical lower limb ischemia are not suited for reconstruction due to occluded crural and pedal arteries, which results in amputation (Keshelava et al., 2009; Roddy et al., 2001). Revascularization may be inappropriate in some cases such as in persons who are wheelchair bound, neurologically impaired, or have extremely limited life expectancy (Abou-Zamzam et al., 2003).

A. Medical Management Before Amputation

1. Smoking cessation as early before surgery as possible until healing is complete

2. Control of diabetes using sliding scale insulin as necessary

3. Control of hypertension

4. Control of pain

a. Prolonged pain may result in poor nutrition.

b. There is some evidence that preamputation pain increases the risk for phantom limb pain.

5. Treatment of infection

a. It can be difficult to distinguish between colonization of exposed tissue and infection.

b. A surface culture on an undebrided ulcer may demonstrate only skin bacteria.

c. Culture of tissue should be done following sterile debridement with bone curetting if indicated.

d. Empiric antibiotics should be initiated until culture and sensitivities are available (Attinger et al., 2002; Bacharach, 2001; Bloomquist, 2001; Datta, 2001; Deery & Sangeorzan, 2001; Gibson, 2001; Lawson, 2005; MacVittie, 1998; Zgonis et al., 2008).

B. Indications for Amputation

1. Severe, acute ischemia secondary to unreconstructable arterial disease or failed revascularization.

2. Irreversible tissue compromises secondary to acute and prolonged ischemia.

3. Chronic ischemia resulting in rest pain, gangrene, nonhealing skin lesions, and osteomyelitis or tissue infection unresponsive to aggressive wound care and antibiotics.

4. Massive muscle necrosis.

5. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens—rare.

6. Nonvascular intractable pain—rare (Durham, 2000; Helt & Jacobsen, 1999; Honkamp, Amendola, Hurwitz, & Saltzman, 2001).

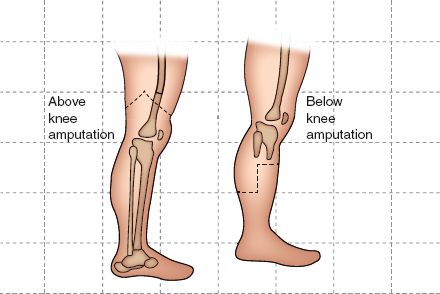

C. Selection of Level of Amputation. Clinical judgment and diagnostic testing are used in the determination of the level of amputation. The goal of level selection is to identify the most distal site at which the amputation will reliably heal and also yield a stump that may be readily fitted with a prosthesis. Major amputation increases the energy of ambulation by 10% to 40% for below-knee amputations, 50% to 70% for above-knee amputation, and 60% if ambulating on crutches without a prosthesis (Attinger et al., 2002; Durham, 2000). Persons with a more proximal amputation seem to have more functional impairment than those with a more distal amputation (Amputation and Amputation Surgery, 2011; Peters et al., 2001; Wehmer & Jones, 2014).

D. Techniques

1. General principles of amputation include:

a. Choosing a site after demarcation

b. Debridement of nonviable tissue

c. Appropriate use of antibiotics

d. Gentle handling of tissues

e. Preservation of all blood supply

FIGURE 25.1 Levels of amputation.