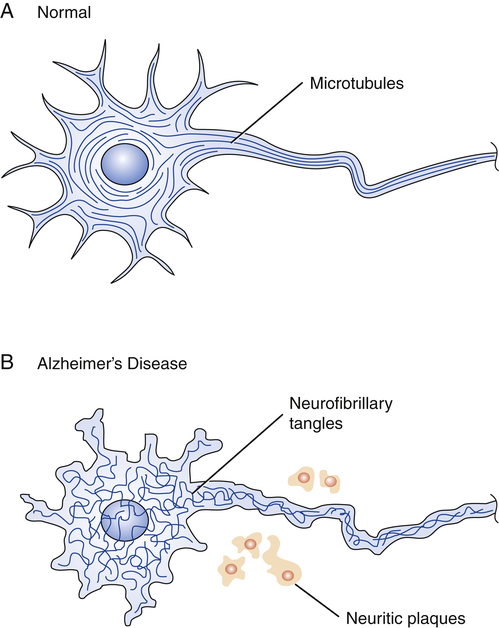

CHAPTER 22 Like neuritic plaques, neurofibrillary tangles are a prominent feature of AD. These tangles, which form inside of neurons, result when the orderly arrangement of microtubules becomes disrupted (Fig. 22–1). The underlying cause is production of an abnormal form of tau, a protein that, in healthy neurons, forms cross-bridges between microtubules, and thereby keeps their configuration stable. In patients with AD, tau twists into paired helical filaments. As a result, the orderly arrangement of microtubules transforms into neurofibrillary tangles. Alzheimer’s is a disease in which symptoms progress relentlessly from mild to moderate to severe (Table 22–1). Symptoms typically begin after age 65, but may appear in people as young as 40. Early in the disease, patients begin to experience memory loss and confusion. They may be disoriented and get lost in familiar surroundings. Judgment becomes impaired and personality may change. As the disease progresses, patients have increasing difficulty with self-care. Between 70% and 90% eventually develop behavior problems (wandering, pacing, agitation, screaming). Symptoms may intensify in the evening, a phenomenon known as “sundowning.” In the final stages of AD, the patient is unable to recognize close family members or communicate in any way. All sense of identity is lost and the individual is completely dependent on others for survival. The time from onset of symptoms to death may be 20 years or longer, but is usually 4 to 8 years. Although there is no clearly effective therapy for core symptoms, other symptoms (eg, incontinence, depression) can be treated. In addition, resources are available to help families cope with AD and prepare for future caregiving needs. TABLE 22–1 Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease Mild Symptoms Confusion and memory loss Moderate Symptoms Difficulty with activities of daily living, such as feeding and bathing Severe Symptoms Loss of speech To detect beta-amyloid accumulation, two tests are used most widely: • Positron emission tomography (PET). The test uses a radiolabeled compound—–usually florbetapir or Pittsburgh Compound B—–that binds with beta-amyloid, and thereby renders beta-amyloid visible in the scan. • Measurement of beta-amyloid42 in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). A low level of beta-amyloid42 in CSF indicates a high level of beta-amyloid in the brain. To detect neuronal degeneration or injury, three principal tests are employed: • Measurement of tau in CSF. A high level of tau suggests neuronal injury. • PET scan showing fluorodeoxyglucose uptake. Synaptic dysfunction of AD is suggested by reduced fluorodeoxyglucose uptake at specific sites in the temporoparietal cortex. • Structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI). Neuronal degeneration of AD is indicated by a specific pattern of atrophy involving the medial, basal, and lateral temporal lobes, as well as the medial and lateral parietal cortices. In 2011, the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association issued revised diagnostic criteria for AD. The new criteria update those issued in 1984 by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS) and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (ADRDA), now the Alzheimer’s Association. Under the revised criteria, AD is divided into an asymptomatic preclinical phase and two symptomatic clinical phases: (1) mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to AD, and (2) probable dementia due to AD. Diagnosis of the preclinical phase is based solely on biomarkers. For the two clinical phases, diagnosis is routinely based on the clinical evaluation. However, although biomarkers are not required for these diagnoses, biomarkers can be used to compliment the clinical evaluation. The new guidelines are available online at www.alz.org. Diagnostic criteria for all-cause dementia and probable dementia of AD are summarized in Table 22–2. As indicated, dementia of any cause is defined by deficits in two or more cognitive areas—memory, decision making, language, personality, visuospatial function—that are severe enough to interfere with function at work or in usual daily activities. In addition, these deficits must represent a decline from a previous level of functioning, and they must not be due to delirium or a major psychiatric disorder. TABLE 22–2

Alzheimer’s disease

Pathophysiology

Neurofibrillary tangles and tau

Risk factors, symptoms, biomarkers, and diagnosis

Symptoms

Disorientation; getting lost in familiar surroundings

Problems with routine tasks

Changes in personality and judgment

Anxiety, suspiciousness, agitation

Sleep disturbances

Wandering, pacing

Difficulty recognizing family and friends

Loss of appetite; weight loss

Loss of bladder and bowel control

Total dependence on caregiver

Biomarkers

Diagnosis

Probable dementia due to AD.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Alzheimer’s disease

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access