Aesthetic knowledge development

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Chinn/knowledge/

The first requisite [of nursing] is the practical belief that the greatest likeness among humans is their difference. The unspoken lesson of anatomy, the autopsy room, chemistry lab builds up the insidious biological impression of the body as a predictable entity—no wonder normal and alike become confused!

Katherine Brownell Oettinger (1939, pp. 1224-1225)

This opening quote, which was penned more than 70 years ago, remains timeless. Oettinger acknowledged the core premise of aesthetic knowing: that situations and humans, while alike in general and predictable ways, remain unique and different. Aesthetics focuses on knowing how to understand and act in relation to those individual differences to create a positive outcome. Oettinger understood that those aspects of humanness that make people alike fall within the realm of empirics, and she cautioned that “alike” is not necessarily the same as “normal.” Oettinger implied that, although humans do generally share things in common (e.g., certain features of anatomy and physiology), they are more alike in their uniqueness. Although empirics addresses what is common and predictable, it is aesthetic knowing that helps us know how to deal with circumstances that are unique to the situation.

Consider the following example. You are working with a certified nurse practitioner in an outpatient clinic when a scantily dressed 13-year-old girl we’ll call Niki arrives and, after the usual preliminaries, is escorted to an examination room accompanied by her mother. As you and the nurse practitioner review Niki’s intake questionnaire, you notice that she is complaining of urinary frequency and burning and that her urinalysis showed results that are typical of a urinary tract infection. A pregnancy screen also reveals that Niki is pregnant, although this is not acknowledged on her questionnaire. You discuss your approach to care with the nurse practitioner, recognizing the probable diagnosis and pregnancy. In this situation, you will consider the empirical data: the urinary dipstick results, the pregnancy test, the reported symptoms, and the indicated treatments. You might also consider the ethics of questioning Niki about sexual activity or abuse given her young age and the presence of her mother. You acknowledge your personal knowing as someone who is a bit intolerant of parents who would let a young girl dress so provocatively, and you tell yourself to keep those attitudes in check; you also are aware of a deep compassion for this child who may be in a very precarious situation. You understand through emancipatory knowing that this type of dress is promoted as socially acceptable for young women despite its possible harmful consequences, but you do not believe that addressing Niki’s appearance is appropriate until you have more information about the situation.

Before going into the examination room, you and the nurse practitioner briefly discuss your plan. The plan includes, in part, that you expect to work with Niki and her mother from a place of deep compassion for the plight of the young girl. You will do an assessment to uncover any other problems or issues that might require attention, and you will explore more about the situation in the home and at school. After you get a clearer picture of the situation, you will discuss a possible plan of care with Niki and her mother and finish with some preventive teaching about her pregnancy and urinary tract infection prevention. You have thought about the aesthetics of your encounter, and you plan to try to create the best outcome by gaining Niki’s trust before broaching the subject of her sexual behavior or possible abuse when her mother is asked to go to another room, where she will talk with the nurse practitioner. You do not know whether Niki’s mother knows that her daughter is pregnant, and you are not sure how best to reveal it, but you do know that knowledge of her pregnancy must come out during this visit. This type of planning integrates all of the knowing patterns, whether they are recognized or not, and it considers what, in general, seems reasonable for this situation.

As you open the door and enter the room, you notice immediately that something is terribly wrong and that the situation is not what you expected it would be. Your eyes immediately go to Niki, who has obviously been crying. The clothes she was wearing are awry, and she is sitting on the examination table as far away from her mother as possible. Her mother is looking rather angry. The look on your face and your hesitation registers your surprise at what you see, and, before you can say anything, Niki’s mother angrily declares, “This little slut just told me she’s pregnant.” You immediately move to creatively deal with the situation. The anger of the mother may be the first thing you attend to, but then you immediately consider other elements of the situation: how Niki looks; the fact that her clothes are awry, which suggests a minor physical confrontation; and the body language that indicates momentary estrangement. You notice these as well as countless innumerable other things all at once. Your assessment is not linear or conscious, and you say and do something immediately to assuage the mother’s anger. On the basis of the unique response that you receive after this action, you make other moves that include verbalizations and movements. You continue this sort of “artful dance,” balancing and tempering your ongoing responses according to the responses received from Niki and her mother. Eventually, the situation calms down; this is the outcome that you envisioned and successfully created during this encounter.

To recount the how, what, and why of your actions is not possible, because they occurred immediately in the moment and with a consideration of elements that were present but not consciously and deliberatively recognized. Basically, you acted in a way that moved this situation to a desired outcome. This is the nature of aesthetics. What you did was act, and you acted in a way that was artful: balanced and, in a sense, beautiful, rather than clumsy or uncertain. You completed a transformative art/act in that you transformed a situation of extreme anger into a situation of calm. You did this rather quickly by noticing and responding to the whole situation all at once. This situation was totally unique and will never be duplicated exactly, and it could only be understood and managed in the moment. Moreover, although you know you acted artfully, you could never fully explain what you did.

As another example to consider, some degree of postsurgical pain is an expected common human experience after hip replacement. However, the expression and experience of pain differs for those who believe it is something to be endured, for those who are fearful of addiction to prescription pain medication, and for those who believe that pain is necessary for healing. It is through the pattern of aesthetics that the nurse ascertains such nuances of meaning for the common experience of pain and creatively works within the situation. The nurse’s goal is to artfully transform the experience of pain into a therapeutic level of comfort in persons despite their individual meanings for and responses to the pain experience.

This chapter details the pattern of aesthetics. Aesthetic knowing in nursing is that aspect of knowing that requires an understanding of deep meanings in a situation and that, on the basis of those meanings, calls forth the creative resources of the nurse that transform experience into what is not yet real but envisioned as possible. It is the dimension of knowing that understands how human experiences that are common (e.g., the teenage pregnancy of our example) are expressed and experienced uniquely. In practice, aesthetic knowing is expressed by means of transformative art/acts.

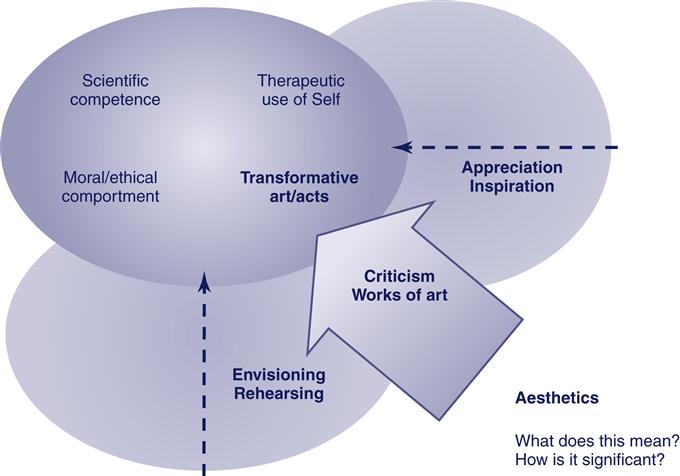

Figure 6-1 depicts the dimensions of aesthetic knowing. In our model, the aesthetic pattern of knowing in nursing requires asking the questions, “What does this mean?” and “How is it significant?” From these questions, the creative processes of envisioning and rehearsing nurture the artistic expression of aesthetic knowing. Aesthetic knowing can be shared to some extent through its formal expressions of aesthetic criticism and works of art. Things such as poetry, stories, and photographs are also artful forms of expression for aesthetic knowing. These formal expressions provide for the discipline a source of appreciation and inspiration that further nurtures aesthetic knowing. In practice, aesthetic knowing is expressed in transformative art/acts in which the nurse moves experience from what is to a new realm that would not otherwise be possible.

As nurses move into caring encounters, they have some idea of situational factors that might be present on the basis prior experiences with similar situations. In the example involving Niki, the nurse (i.e., “you”) moved into the encounter having asked and answered the critical questions, “What does this (situation) mean?” and “How is it significant?”; with the nurse practitioner, you made a plan based on your past experiences with similar situations. However, as soon as you entered the room, those same questions were asked again, all at once in the moment, although not deliberatively or with conscious intent. After the meaning that the mother was angry was apparent, you sensed (envisioned) what was required is to calm the situation and, in the moment, you selected a response. You had various responses stored up in your background of experience both in practice and from deliberate rehearsal of different kinds of responses that you could call forth in an unexpected situation that required a calming influence. Because you have practiced how to calm a situation and you knew that you could be effective when doing so, you acted in this situation with skill and confidence. You continued to ask the critical questions and to envision a desired outcome, and select from various rehearsed possibilities all at once; this is the essence of the transformative art/act.

As you reflect on this situation, you could write about it to describe the situation and your own internal experience of the scenario as it unfolded. As you begin to explore what it all meant or could mean and how your education and experience informs your reflection of the situation, you create an aesthetic criticism. Such a written account will never be as rich as the actual situation, but certain elements can be expressed. Alternatively, you might write a poem or create a drawing that represents the situation. After such a work has been created, others can ask the critical questions “What does this mean?” and “How is it significant?” as they review and study the formal expressions of your aesthetic knowing. They could ask themselves if your representations helped them to appreciate the meaning and significance of the situation and if its meaning and significance inspire them in a way that would be helpful in their own practices. As a preceptor, mentor, or teacher, you might guide your students to rehearse and envision what they might do in a similar setting as a way to help them to cultivate aesthetic knowing. In these ways, others learn how to more effectively create transformative art/acts.

In this chapter, we begin with a discussion of the meaning of art and aesthetics as the background for our conceptualization of aesthetics in nursing. Next, we present a conceptual definition of the art of nursing and discuss our definition in the light of other conceptualizations of the art of nursing that have appeared in nursing literature. Finally, we focus on the dimensions of aesthetic knowing as represented in Figure 6-1.

Art and aesthetics

Aesthetics is a noun that derives from the Latin and Greek words that refer to perception. It has evolved to refer specifically to the study of and ideas about artistically valid forms. The adjective aesthetic identifies an object or experience as being artistically valid. That which is artistically valid is coherent in form and substance and thus conveys a meaning of a whole beyond the formative elements; the artistically valid also evokes a response. In the following sections, the terms aesthetic and artistically valid are used interchangeably.

Consider the famous painting Mona Lisa. Aesthetics would address theoretic and philosophic views about its artistic validity. If an art critic declared the painting to be artistically valid, it would mean, in the critic’s view, that it had a coherence about it that conveyed some meaning that was understood across multiple critics. Coherence may be proposed because of color contrast and proportion within the painting that emphasize the subject’s large figure and face. The response that is evoked is one of interest or mystique.

The nature of aesthetics

The aesthetic does not necessarily equate to that which is commonly viewed as beautiful or lovely. The standards by which something is taken to be appealing or beautiful vary widely in different disciplines and within different contexts and cultures. Individuals, given their unique perceptions and tastes, respond differently to an art object or experience. In the philosophy of aesthetics, beauty is not taken a matter of taste. Rather, it takes a form that brings forth a response that draws one in to notice what is expressed. The substance of what is addressed as beauty in philosophy may, in fact, represent something like shame, grief, or death. However, the form is considered beautiful in that it satisfies aesthetic criteria and thus is considered to be artistically valid.

There are general traits that distinguish what is artistically valid or aesthetic in form from what is not. That which is artistically valid places various elements into a pattern to form a whole that symbolizes meaning beyond the elements themselves. The form evokes a response, a feeling, an insight, or a sense of connection with the experience portrayed in the art. The response that art evokes is very often strong or even transformative, which means that the experience of the art is unforgettable, it leaves a strong impression, or it provides insight into the human condition.

The meanings that are conveyed and the responses that are evoked are connected to the cultural heritage from which the art form arises. Those outside of the culture may not fully recognize the meanings that are derived from the culture, but they can still recognize the work as artistically valid; they will recognize the wholeness of the form and see that there is meaning in the work, although the meaning may be different from that which arises from the culture of origin of the work. The cultural heritage of nursing points to the primacy of interpersonal interactions so that nurses will tend to be drawn to works that evoke a sense of caring and meaningful interpersonal connection.

The nature of art

Art is both the process of creating an aesthetic object or experience as well as the product that is created. The process of creating and what is produced must display characteristics that are artistically valid to properly be called “art.” Art is not limited to the fine arts or to what is often labeled as art. Rather, art is present in all human activities that involve forming elements into a whole (Chinn & Watson, 1994; LeVasseur, 1999; Sandelowski, 1995). In our example of Niki, the transformative art/act was art in action, and it was artful because the nurse’s actions and being were in synchrony with all that unfolded as part of the situation; the nurse was an integrated part of a whole and created an unfolding of possibilities that would not otherwise have been possible.

Art is not defined by taste or by what someone likes. Matters of taste or preference, such as “I like that painting (or what that nurse did)” or “I do not like that painting (or what that nurse did)” do not define something as being art. Neither is art in the traditional sense considered art because it can be sold for profit. For example, a local “art show” might sell out of its posters of a popular rock band, but this does not mean the poster was in fact a work of art. Rather, the extent to which art as process is satisfying and the extent to which art the product assumes coherence as a whole and elicits a feeling response determines the extent to which the experience can be called “art” (Eisner, 1985).

Art as a process requires skill in the technical and mechanical aspects of working with the elements from which the product is formed. It also requires an ability to imagine the whole before it is expressed and to creatively integrate elements of form into a whole. This process can be readily illustrated in the fine arts, where, for example, a musician acquires technical and mechanical skills with an instrument and learns to bring the elements of sound together into a musical performance that generates a response from the listener. Art as a product creates a response that can transform experience. This transformation of experience occurs when a person—whether an observer or a participant—is drawn into a realm that would not otherwise be accessible, such as the realm of chaos that a performance of Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries might engender.

In summary, art is the process and product of bringing diverse elements together into a whole that evokes a response and that moves one’s experience or perception into a realm that is not otherwise possible. Aesthetics concerns the nature and characteristics of art as process and product to determine the extent to which what is said to be art is in fact artistically valid in form.

Art and aesthetics in nursing

Nurses have a notable history of appreciating art and of creating aesthetically pleasing environments to enhance healing and well-being. Familiar examples include the use of music to create a sense of calm, visual arts to convey health and illness experiences, dance or free-form movement to enhance physical coordination and strength, and drawing as a therapeutic modality. Works of art have also been used to illustrate and interpret meanings of health and illness experiences in education and research (Chinn & Watson, 1994; Darbyshire, 1994; Lamb, 2009; Pellico & Chinn, 2007). Although we acknowledge and encourage these therapeutic uses of artistic processes, this is not the focus that concerns aesthetic knowledge development, and this is different from what we are addressing as “the art of nursing.” Rather, aesthetic knowledge development is directed toward those aspects of knowing that are essential to the “doing” of nursing itself, which is what we consider “the art of nursing.”

Aesthetics is typically associated with what is commonly seen as art. It is perhaps because of this that aesthetics as not had much emphasis in nursing. However, aesthetics has always been integral to nursing practice. Aesthetic qualities can be seen as art in all aspects of nursing practice: from notes written in a chart to theoretic formulations, from a single brief interaction with an individual to sustained interactions with groups and communities, and from an unexpected encounter to a thoughtfully planned design for a system of care. In all of these ranges of nursing experience, nurses artfully draw on and use emancipatory, empiric, ethical, personal, and aesthetic knowing. It is the dimension of aesthetic knowing that endows nursing experiences with aesthetic qualities and that differentiates excellent and skilled nursing from the impersonal performance of technical acts and routinized procedures.

Moreover, things that ordinarily would not be labeled as art do have aesthetic characteristics (Sandelowski, 1995; Wainwright, 2000). For example, an empiric theory is formed from conceptual ideas that are linked in a pattern that has a meaning that the concepts taken alone could not convey. The appeal (i.e., a subtle feeling response) of a theory often derives from the aesthetic shape of the theory. Without this quality, the theory lacks a certain attractiveness or appeal to the community of scientists.

Aesthetic knowing

Aesthetic knowing requires knowledge of the experience toward which the art form is directed as well as knowledge of the art form itself. For example, the poet requires knowledge of a life experience that is reflected in the poem as well as knowledge of the art form in the manner of the techniques and methods that are used to create something that can be considered poetry (Kramper & Thawley, 2009). The visual artist requires knowledge of the experience or situation that will be visually presented as a painting or sculpture as well as knowledge of the technical aspects of painting or sculpting that are required to achieve the desired visual representations.

In nursing, aesthetic knowing requires knowledge of the following:

• The experience of nursing (the art form)

• The experience of health and illness (that which nursing art/acts transforms)

These two aspects of knowledge grow as nurses are educated, as they have experiences in practice, and as they learn about the experiences of other nurses. For example, nurses learn about the experience of dying by studying theories of death and dying, by reading or hearing stories about dying, and by caring for people who are dying and experiencing their feelings and those of their loved ones. Nurses learn about caring for someone who is dying as they are guided through this kind of clinical experience in school, as they hear the stories of other nurses who have cared for people who are dying, and as they experience working with people who are dying.

Background knowledge of the experience of nursing and of the experiences of health and illness are essential, but they are not sufficient for aesthetic practice. For example, to bring an aesthetic quality into the experience of caring for someone who is dying, you also need to cultivate the ability to enact nursing’s art form itself, which is the focus of this chapter and which Figure 6-1 depicts. The following section details various conceptions of nursing art that form a foundation for our approach to developing aesthetic knowing and knowledge in nursing.

Conceptual definitions of the art of nursing

As Johnson (1994, 1996) demonstrated, the idea of the art of nursing has had several different meanings reflected in the nursing literature since the time of Nightingale. Although no single clear definition of the art of nursing prevails, nurse scholars have consistently recognized the art of nursing and emphasized how vital this aspect of nursing is in relation to who nurses are and what they do. Although historically nursing art referred largely to technical skills that were often learned in the “nursing arts laboratory,” the art of nursing has taken on a meaning that is more closely related to art as aesthetic practice.

The art of nursing as aesthetic practice can be a difficult concept to understand. One difficulty is that the nurse’s art is expressed in the knowing-being of the nurse. Briefly, nursing art does not simply reflect what and how the nurse knows (epistemology); it also refers to the nurse’s being and doing (ontology). The embodied nature of “the art of nursing” is part of what makes it difficult to understand. The term embodied means that nursing art requires mind-body-spirit involvement in a creative experience that is transformative. The body moves through the nursing situation, the mind understands meaning, and the spirit feels—all at once—and artfully acts to transform experience. In this sense, nursing art is a form of performance art that involves the nurse and the person to whom the nurse is providing care. Like a theatrical production or an orchestral concert, the nurse’s performance art can have various degrees of artistic validity. As with all art forms, artistic skill can be taught and learned. Even for those who are most talented in the art form, artistic competence requires discipline and practice; it does not come naturally.

Recognizing the challenges that are inherent in defining the art of nursing, we propose a definition that was derived from an aesthetic inquiry project that began as the result of conversations with practicing nurses who, without exception, recognized meaning in the phrase “the art of nursing.” Conversations and storytelling among nurses focused on their experiences of the art of nursing, the various meanings that they saw in photographs, or in rehearsals or the role-playing of various alternative approaches to nursing practice (Chinn, 1994, 2001; Chinn, Maeve, & Bostick, 1997). The conversations with nurses were supplemented with introspection and more formalized aesthetic inquiry techniques carried out by project leaders. Chinn, Maeve, and Bostick observed nurses as they practiced nursing, reviewed photographs of nurses as they practiced, and used journaling to explore deeper symbolic and personal meanings of the practices observed.

The definition that emerged from this aesthetic inquiry project and that we are subsequently using in this text is as follows:

The nurse’s synchronous arrangement of narrative and movement into a form that transforms experiences into a realm that would not otherwise be possible. The arrangement is spontaneous, in-the-moment, and intuitive. The ability to make the moves that are transformative is grounded in a deep understanding of nursing, including relevant theory, facts, technical skill, personal knowing, and ethical understanding; and this ability requires rehearsal in deliberative application of these understandings. (Chinn, Maeve, & Bostick, 1997, p. 90)

This definition identifies synchronous narrative and movement as the elements that nurses use to form the aesthetic experience, which is what in this textbook we refer to as the transformative art/act. Narrative includes words, gestures, and intonations of speech. Synchrony refers to the coordination and rhythm of the experience. Synchrony of intention and action is also implied. Synchrony and narrative must come together to form an integral whole. In the example of Niki, narrative would include elements such as what you said, the somewhat surprised look on your face when you entered the room, and the loudness or softness with which you spoke at different times when trying to restore calm. Synchrony refers to how you moved your embodied self within the situation; who you approached and when; how and where you touched Niki or her mother with the intent to calm, as well as how you were synchronizing your words with what you were doing. Synchronous narrative and movement as the elements that form the aesthetic in nursing are critical features of the Chinn, Maeve, and Bostick (1997) definition that provide a basis for teaching and conveying aesthetic knowledge and knowing.

Johnson (1994) identified five conceptualizations for the art of nursing:

• The ability to grasp meaning during patient encounters

• The ability to establish a meaningful connection with the person being cared for

• The ability to skillfully perform nursing activities

• The ability to rationally determine an appropriate course of nursing action

Grasping meaning during patient encounters.

In our definition of the art of nursing, the ability to grasp meaning during a patient encounter is required if the nurse is to transform an experience from what is to what is possible. Our explicit reference to the intuitive, in-the-moment arrangement of movement and narrative refers to the intuitive element as it unfolds within the transformative art/act and not to intuitive elements that inform or point to a specific outcome or problem. In other words, as a nurse in the moment of care, you may not have an immediate grasp of what the moment means to a person or family and what to do about it. Rather, your intuitive sense detects all that is going on and calls forth a response, and you act spontaneously to care for the person or family in the moment (Billay, Myrick, Luhanga, & Yonge, 2007).

The focus from which your art form emerges is the intuitive use of your creative resources to form experience. You are open to making moves within an experience that you have not anticipated and planned, and you have not necessarily confirmed the patient’s or family’s perceptions of the situation. Rather, your moves come from a perceptual grasp of the various possibilities for forming the situation that resides within the experience. Your own creative energy moves the encounter forward as a work of art in process.

As a way to better understand what is meant by “grasping meaning in the situation,” think about how you cannot really know how to be in a situation until you are actually in it. As an experienced practitioner, as you move into clinically complex care situations, you comprehend—all at once—what a situation is calling forth, and you respond wholly. As you respond, your being and your behavior call forth in the other or others a response that they in turn wholly understand and to which they respond. These sorts of all-at-once, instantaneous, and simultaneous response patterns, which transform the experience in the moment, constitute the art/act.

The intuitive aspect of creating form is what is referred to as creativity. It is a knowing in the moment of creating that enables the artist to express unique possibilities that fit together, make sense for the situation, and come together in the right relationship. It then follows that the intuitive perception of a right relationship within a nursing encounter depends upon a deep grasp of the meaning embedded in the situation.

Although our definition is clearly applicable to patient encounters, it also applies to nursing actions that do not involve a direct patient encounter. The ability to design a system of care is grounded in a grasp of meaning in the experience of people for whom the system is designed. Here, spontaneous and intuitive aspects of the process of creating the design are part of the formative process. The nurse-designer does not intuit an end point and set about to design it. Rather, the nurse-designer is immersed in the experience of creating the design and remains open to a stream of possibilities that can only emerge as the design takes shape.

Establishing a meaningful connection with the person being cared for.

Our definition of the art of nursing assumes a deep and meaningful connection with the other. A transformative move requires presence with the other. If an art/act is transformative and artful, it must be grounded in a profound level of connection between the nurse and the other. In the context of such a connection, there is a synchronicity or rhythmicity between the nurse and the other. The “synchronous arrangement of narrative and movement” in an interaction refers to the timing and flow among all elements in the situation and reflects a deep level of connection between the nurse and the person for whom care is being provided.

Skillfully performing nursing activities.

The performance of nursing skills is one of the earliest conceptualizations of nursing art, and it is an element of meaning that often was expressed by nurses who participated in Chinn’s aesthetic inquiry (Chinn, 1994; Chinn et al., 1997). Nurses first pointed to tasks and procedures that are required in the “doing” of nursing, noting that it is how they do what they do that characterizes their art. However, in our definition, skills alone do not constitute the art of nursing. Rather, skillful performance is expressed in the nurse’s movement and narrative, which may or may not involve tasks and procedures. Skillful performance is developed over time from a background of practice (rehearsal) that makes possible what Heidegger identified as “ready-to-hand” knowing (Heidegger, 1962). Artful nursing includes and indeed often requires skilled technical performance. However, our definition implies an integration of skill with relevant theory, facts, and personal knowing as well as with emancipatory and ethical understanding.

Rationally determining an appropriate course of action.

Research regarding clinical judgment and rational reasoning suggests that intuitive and aesthetic components are necessary for sound practice (Benner, Tanner, & Chesla, 1996; Mattingly, 1994). In our conceptualization of the art of nursing, rational reasoning is not a defining element. Rather, rational thinking ability and clinical judgment processes, like technical skills, comprise the background that is necessary for aesthetic capability. Nursing art as synchronous movement to transform experience is an art form; it is not rationally formed, and there is no “outcome” that is defined in advance. Like other art forms, the nurse has a vision or an idea of what improved health and well-being would be like for a person in a particular situation. However, the exact outcome of a particular situation is not projected in the moment of the transformative art/act. Rather, the direction of health and well-being is intuitively shaped and formed as it occurs. In this sense, the creation of health and well-being is like a “work in progress.”

For example, a composer makes use of accepted theories of rhythm when constructing a musical score and has an idea about what the music might be like in the end. However, during the process, she is inspired to integrate rhythmic variations that may defy common conventions, and the exact form of the music shifts as it unfolds. In the process, the composer places a unique signature on the work that gives it artistic character. The final score is generally like what the composer envisioned, but it is not exactly what might have been predicted at the outset. Likewise, as a nurse, you call on your theoretic understanding of a particular type of illness experience when developing a rational plan of care to point toward appropriate nursing action. Although you do plan, you remain open to spontaneous events that create opportunities to change the plan as the caring process unfolds in synchrony with the person and family involved in a particular experience. It is this spontaneous unfolding of the process, when integrated with your prior rational understanding, that creates artistic form. The particular ways in which the nurse shifts or moves through the experience is the artistic signature that endows the experience with a particular and unique quality.

Morally conducting one’s nursing practice.

Our definition of the art of nursing points to ethical understanding as background that is essential for aesthetic practice. There is a significant ethical dimension that is inherent in the transformative art/acts that are basic to the art of nursing. Transformative art/acts create change with regard to what would otherwise happen. Nurses who participated in the aesthetic inquiry from which our definition was derived told many stories of their practices that involved ethical dilemmas and that elicited actions that they associated with the art of nursing. There is a value component in the idea of transformative art/acts that implies a significant ethical dimension being inherent to the art of nursing in that transforming creates a change in what something is to what it otherwise would not be. In the context of nursing, the change is, by definition, one toward a higher level of health and well-being. A transformative art/act could not be recognized as artistically valid if it violates ethical sensibilities. However, transformative art/acts alone do not convey ethical understanding (Vezeau, 1994). Rather, transformative moves can come out of significant ethical and moral dilemmas and thereby contribute to the development of ethical sensibilities (Maeve, 1994).

The dimensions of aesthetic knowing

As seen in Figure 6-1, the dimensions of aesthetic knowing include the following critical questions: “What does this mean?” and “How is it significant?” These critical questions engage the creative processes of envisioning and rehearsing possibilities. From these creative processes, aesthetic criticism can be constructed as a form of knowledge of the artistry of nursing that can be shared with others. Works of art also emerge as representations of what is known, and they are also a form of aesthetic knowledge that can be made available to the broader audience within and outside of the discipline. Art forms that can be created in nursing to represent the meaning and significance of nursing and health experiences include poetry, photography and other visual art forms, story, drama, and dance (Chinn & Watson, 1994). The authentication processes of appreciation and inspiration examine the extent to which formal expressions of aesthetic knowing are aesthetic in nature and thus can be used to cultivate aesthetic knowing in nursing. Transformative art/acts are the integrated expressions of aesthetic knowing in practice. These art/acts are characterized by synchronous movement and narrative that transform the health–illness experience from what is into a realm that would not otherwise be possible.

Critical questions: what does this mean? how is it significant?

The critical questions for aesthetic knowing ask the following: “What does this mean?” and “How is it significant?” These questions can be asked of formal expressions of knowing or in the context of practice to create a transformative art/act. As a nurse engages in transformative art/acts, various possibilities emerge instantaneously in the moment, without conscious thought. Outside of practice, those questions initiate an envisioning and rehearsing process that is conscious and deliberative and that can be used to cultivate aesthetic knowing.

Creative processes: envisioning and rehearsing

Envisioning and rehearsing are two interrelated processes from which creative products of aesthetic knowing emerge. Typically, envisioning and rehearsing have not been deliberately taught nor do nurses identify these processes as something that they do. However, many of the practices that Chinn, Maeve, and Bostick (1997) came to view as envisioning and rehearsing were activities in which nurses engaged. Often these activities were hidden from view, engaged in during the nurses’ time away from job responsibilities, and assumed to be insignificant and trivial yet often necessary to cope with difficult situations. For example, as nurses described situations that represented their art, they related how they told one another stories about the situations in phone conversations after work, over a meal, or in a secluded area during a downtime. Their storytelling episodes always included an account of the response of the listener and the ways in which their interactive talk formed and reformed how they saw similar situations and how they came to trust their own intuitive senses. When the nurses associated these and similar activities as being necessary and important aspects of developing an aesthetic knowing of their art form, the importance of these activities was immediately grasped.

Envisioning involves imagining a typical end point scenario or a response that one hopes to elicit by the performance or display of the art form. For a comedian, the envisioned obvious end point is the audience’s laughter; a less obvious but hoped for end point is that the audience will catch subtle meanings conveyed in the comedy (i.e., that they will “get” the point of the joke). For a musician, the envisioned end point for a particular piece of music might be to convey a sense of longing, a sense of joy, or a sense of excitement. For a novelist, the envisioned end point is transporting the reader into a realm outside of that reader’s own experience and into the realm of the characters and situations depicted in the novel. For a nurse, envisioned end points are those that represent health and well-being, such as calm, relaxation, comfort, and the ability to navigate a certain health-related situation.

Rehearsal is either a physical or mental walk-through of the skills required for the performance or display of the art form, ultimately involving the presence of a coach, teacher, or critic. The writer presents excerpts or pieces of writing to reviewers for critique and feedback. The comedian engages small audiences to listen and respond to segments of a routine. The musician performs for a teacher or mentor.

A useful analogy for understanding the processes of envisioning and rehearsing in nursing is that of improvisation. In an improvisational art, which includes the art of nursing, the display (or performance) is possible because the performer is skilled in the various moves and sequences that improvisation requires. The skills are developed through repeated practice, thus making it possible for the performer to call these skills forth in a unique situation. Repeated and intense rehearsal and the development of a wide range of finely tuned skills makes the skills fully embodied. Over time, the artist must also rehearse imagined improvisational scenarios before a coach or critic to receive direction that makes it possible for the artist to refine his or her ability so that intended meanings are conveyed.

For example, in improvisational drama, the actor (nursing student) practices sequences of movements (techniques), postural and facial expressions (body language), and voice intonations (soft and soothing or loud urgent speech) that convey wide ranges of emotion (from calm to immediacy). They also practice and narrative lines (“Shh, it’s OK” or “Hurry with that crash cart!”) that give verbal expression to a possible experience (this is going to be frightening for the patient or the patient is going to arrest). The director (critic, coach, or teacher) gives the actor (nursing student) feedback and guidance that lead the actor into new territory. The director (teacher) may also guide the actor (nursing student) to repeat and perfect the sequence of movements to bring them to a refined, embodied level. Eventually, the actor’s skills are so finely tuned that the actor’s focus remains on the process that is emerging in the improvised situation rather than on the technical skills required for the process of improvisation.

In the following sections, we describe three practices for envisioning and rehearsing narrative and movement as elements that are basic to nursing’s art: (1) creating and recreating storylines, (2) creating and developing embodied synchronous movement, and (3) rehearsing and engaging a connoisseur-critic. The practices that we describe are not linear or sequential; they are interwoven and integral to aesthetic knowing. They are presented separately here to describe in some detail what they are and how they function to contribute to aesthetic knowing. Each of these practices fosters both envisioning and rehearsing.

Creating and recreating storylines.

When nurses tell stories to one another, they move into a realm that is created from the imagination and that is not bound by the constraints of the workaday world. Even when the story begins with the intention of conveying an accurate account of a real experience, in the telling of the story, the narrator creates emotion, stresses points of emphasis, exaggerates or downplays selected elements of the story, and selects certain features to include or exclude. Often the desires of the storyteller come into the story in ways that surprise even the storyteller. For example, the storyteller may unexpectedly give an account of what he or she wishes had been done in the situation as if it actually happened rather than accounting for what did happen. In this way, the storyteller forms various types of meanings and significances for the story, thereby providing multiple possible responses to the critical questions of “What does this mean?” and “How is it significant?” If the story were viewed through the lens of empirics, it would have little or no worth. However, when viewed through the lens of aesthetics, the story has exquisite value as a frame from which to explore possible meanings and to create visions and possibilities for the future (Maeve, 1994).

To develop aesthetic knowing with the use of the creative envisioning and rehearsing processes, we recommend that the story be told in the voice of the person who receives nursing care. Stories that are told in the voice of the nurse are more often reflective of personal knowing and explore the nurse’s personal meanings. Stories that are told in the voice of the person receiving nursing care inspire empathy as well as a deeper understanding of the experience that is the story’s focus. Stories told from the perspective of the other also help to develop an embodied knowing of the other’s experience. We recommend stories that illuminate some health or illness experience toward which nursing’s art form is directed.

The story can come from actual experience, but aesthetic storytelling does not require adhering to the factual truth of a situation in the way that an empiric case study or anecdotal account requires. Rather, the storyteller purposely exaggerates, fictionalizes, emphasizes, and reshapes the actual experience to enhance listeners’ perceptions of certain meanings that the storyteller intends to convey in the story. In this way, the story comes from the imagination more than from the actual experience, although the imagination is inspired by the actual experience. The well-developed story will reveal possibilities in human experience that often are not perceived empirically or understood rationally.

The storyline is the plot of the story. A plot requires that the essential characters of a story be placed in a situation that suggests a tension that builds toward an uncertain ending, thereby moving the story toward any one of several possible endings. The storyteller knows which of the uncertain endings will eventually emerge, but the listener or reader can only be drawn into the story if the ending remains uncertain. The listener or reader senses any number of possible endings, some of which are dreaded and others that are hoped for. In the best of stories, the worst possible ending and the best possible ending both remain viable to the listener or the reader until the very end, thus keeping the reader engaged. Characters other than the essential characters can shift and move in and out of the story, but the main characters play essential roles throughout to maintain the tension of uncertainty. This tension of uncertainty is appealing in part because this is exactly the way one’s own real-life story is emerging from day to day and even from moment to moment. Nurses move in and out of people’s real-life stories, often playing essential roles that can and do influence movement toward a hoped-for future.

During the initial creation of a storyline, you typically begin by recounting an experience very much the way it actually happened in practice, with, of course, creative license to embellish along the way. Then, you recreate the situation by telling the story as you might have wished it to unfold. You retell the story and describe your actions (movements and narrative) as you might have acted in the situation, perhaps describing what you wish you had done instead of what you actually did. You continue to create different storylines that involve the same situation, inserting different imagined possibilities for what you might have done and said in ways that you can imagine would lead to a different possible ending.

For example, when recounting the story of Niki in our opening example, you might insert into the story a different approach to your initial encounter with Niki and her mother, when you knew that the pregnancy test was positive but did not know if either Niki or her mother knew that this was the case. You could create a storyline in which you candidly tell Niki and her mother about the results of the pregnancy test; you could then imagine how each of these individuals would react at this point in the unfolding story and how you would handle such a scenario. You might create a storyline in which Niki did not know she was pregnant, one in which Niki’s mother was overjoyed at the news, one in which Niki’s mother became very frightened, and one in which both individuals immediately revealed that there was incest going on in the home and expressed despair regarding how to stop it. Each of these scenarios leads to mentally rehearsing possible creative possibilities that can be used in actual practice.

Creating and recreating storylines serve several purposes that are related to aesthetic knowing. Most importantly, from the perspective of aesthetics, each storyline brings forth new perceptions of meaning that could be possible in the situation. For example, the storylines in the case of Niki provide the opportunity to explore various nursing approaches to the situation and to imagine various different responses from Niki and her mother and how you, or those with whom you share the story, would respond to each of the possible scenarios. The different storylines bring to awareness various meanings that could be present in a care situation. As various meanings come into awareness, new possibilities for creative engagement with each meaning can emerge. Stories elicit profound reflection on meaning that involve both personal meaning and the meaning for others in the story. In this way, the story brings to awareness the aesthetic knowledge that is embedded in experiences and that contributes to aesthetic practice.

Creating and recreating storylines also provide a means of rehearsing a narrative that, in turn, develops knowledge and skill that are basic to the art of nursing. The exact words that emerge during the processes of creating and recreating storylines are not suitable for the actual clinical situation. Rather, the storytelling process itself enhances the nurse’s ability to use narrative effectively in practice.

The narrative that is used to tell a story places the plot within a context; it conveys the “feel,” attitude, and mood of the story, and it integrates the storylines to form a whole vicarious experience that is located within the story’s time and space. The narrative—those verbalizations, gestures, and voice intonations that are used in practice—serves the same functions. Narratives locate the isolated experiences of the person within a larger plot; they contribute to the creation of an atmosphere within which the experience can unfold, and they integrate the various elements of the experience into a whole that moves toward an imagined future. For example, as you imagine various storylines that involve the scenario of Niki and her mother, you form and “bank” any number of possibilities for managing an actual situation that can be called forth when needed. You also form various “moves” (i.e., words and actions) that will constitute who you are as a nurse in like situations. Storylines are considered fiction because, although the initial story is based on a real event, the story is embellished and enhanced as it is told. In this way, stories provide a vehicle for the rehearsal of possibilities that you might be called upon to actualize in your practice at some point in the future. Storylines become etched in your memory in much the same way that actual experience remains with you and that you can call forth at a moment’s notice when needed.

When you create a storyline, you can develop your ideas in writing (Sorrell, 1994) or conversation. You might begin with an anecdotal account of a real experience. The experience can be your own, or it can be an experience that you observed or have heard about. The first account of the experience may seem relatively simple and inadequate for representing the significance of the experience itself, and it may sound clinical because of the culturally acquired propensity to focus on anecdotal accounts of a sequence of events or a clinical case study.

To make a first effort less clinical and more of a story, first explore what it is about this experience compels your attention; identify the key characters involved in the experience; and imagine each character’s perspectives, motives, and intentions. Explore the context within which the experience is set and the key elements of the situation that seem important to the unfolding of the story. Imagine various endings toward which your experience could have moved or may still move. Proposing various endings provides possibilities for building tension within the story that can be significant in different ways and lead to various endings.

Next, sketch out the essential characters whom you wish to place within your storyline. You can shift the characters as your storyline unfolds and changes, but the characters will remain central to the storyline. Begin to write as if you were these characters. As you write, include those elements that you explored that will create richness to your story: the story’s context; the character’s motives, intentions, and perspectives; the key elements of the situation; and so forth. As you begin to write, the elements of the storyline will begin to emerge. Imagine several different possibilities for the movement of the storyline toward an ending, and let one of your imagined possibilities become part of your story. This first narrative will become material that you can work with to recreate the storyline with other possible endings. As other possible endings are created, a richness of meaning emerges.

Creating and recreating storylines provides aesthetic narrative skills that the nurse uses as a participant in the emerging real-life stories of those for whom care is provided. The story that unfolds clinically is shaped and transformed by emerging possibilities that are situated between the past and the future. Mattingly (1994) described this process as “therapeutic emplotment.” The story that unfolds clinically is lived. The aesthetic challenge is to structure isolated episodes into a plot that moves the lived experience toward a hoped-for ending. In our example of Niki, you made a transformative move that fairly quickly brought an explosive situation to a calmer place. However, you are likely to have continuing contact with Niki, and your experience of creating transformative art/acts continues. As Niki returns to the clinic throughout her pregnancy and beyond, you will continue to participate as a player in shaping Niki’s real-life story. As during that first encounter, you will use nursing as an art/act that moves the real-life story that is unfolding toward the best possible future.

In real-life stories, all participants are instrumental in the creation of the plot, the selection of the ending, and the actions that bring about changes and transformations. The plot does not happen by design; rather, it unfolds. The end that participants desire energizes movement toward that end. A nurse’s ability to participate in this aesthetic process is nurtured by skills that are developed through the rehearsal of creating and recreating storylines.

Creating conversational or written storylines that move the situation toward a desired future provides a vision of what might be and an opportunity for the rehearsal of ways in which nursing care can be enacted to energize movement in a new direction. As the actual experience unfolds, what the person and his or her family envision is shaped by everyday experiences. For example, as a nurse assists a person with taking a few first steps after a traumatic injury, the possibility for mobility begins to take form, and along with this possibility comes the potential for returning to a job or re-engaging in a desired activity. The imagined scenarios of one’s new life story gradually begin to take shape as they are formed by the mutual interactions of nurses, family members, and others involved in caring for the person. Read Box 6-1 for an example of this.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree