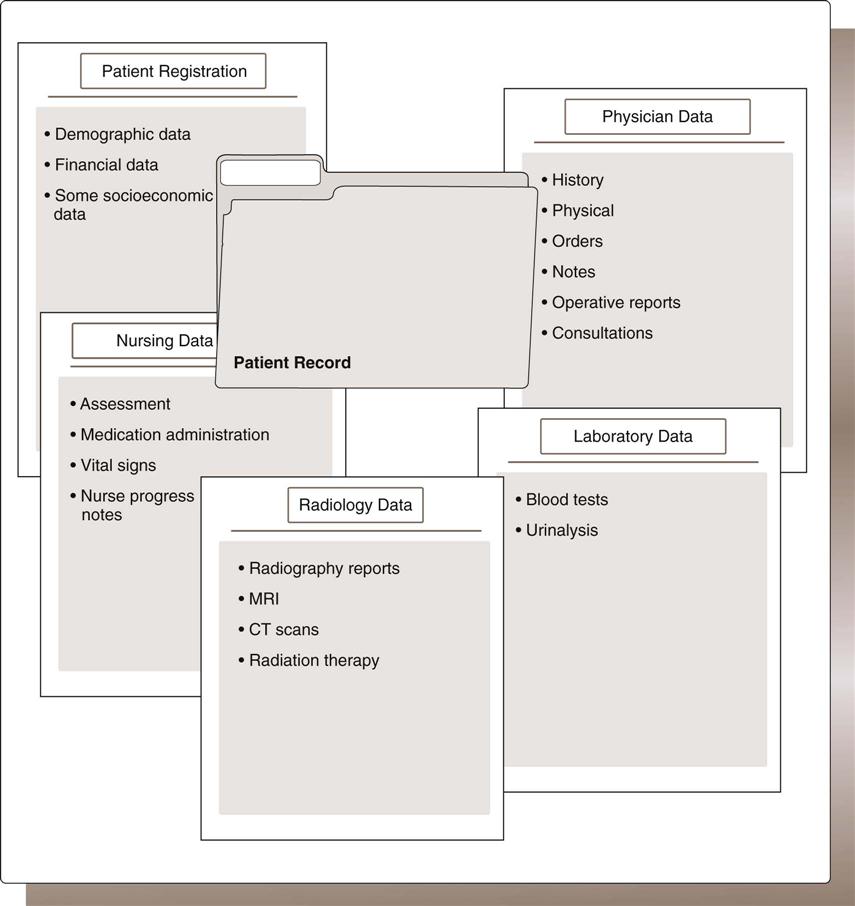

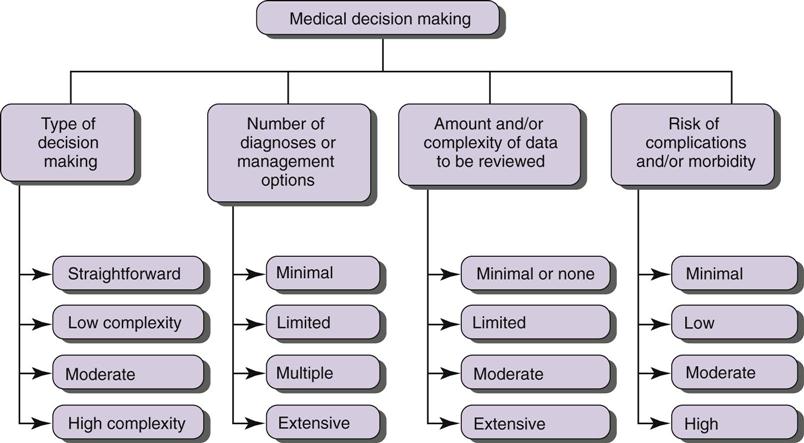

Nadinia Davis By the end of this chapter, the student should be able to: 1. Describe the flow of clinical data through an acute care facility. 2. Given a specific clinical report, analyze the required data elements. 3. Given a data element, identify the appropriate original source of the data. 4. List the elements of the Uniform Hospital Discharge Data Set (UHDDS). admission consent form admission record admitting diagnosis admitting physician advance directive anesthesia report attending physician bar code chief complaint consultant consultation countersigned direct admission discharge summary face sheet general consent form history history and physical (H&P) laboratory tests medication administration nosocomial infection nursing assessment nursing progress notes operation operative report plan of treatment physical examination physician’s order progress notes protocol (order set) radiology examination surgeon telemedicine treatment Data collection begins with building the hospital’s data set for a given patient. Each type of facility has its own particular data set that must be considered in the planning of data collection strategies, inclusive of the discharge data set required for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Demographic, financial, socioeconomic, and clinical data constitute the health record. This chapter is about the clinical data that are collected throughout the patient’s acute care (short stay) inpatient stay by various caregivers in the facility. Throughout the chapter, various paper forms or computer data collection screens are referenced, examples of which are located in Appendix A and Appendix B. In any health care delivery encounter, there is a pattern of activity and data collection that is characteristic of the facility and the type of care being rendered. Although there are unique differences, as will be seen in Chapter 8, most encounters have some basic points in common: patient registration, clinical data collection and evaluation, assessment, and treatment. All patients who seek treatment in any health care setting (e.g., emergency department, clinic, inpatient unit) within a hospital must be registered. Inpatient admissions usually correspond to one of the following four scenarios: A physician must write an order for a patient to be placed in a bed in the hospital. The patient’s status is defined in the order: inpatient or outpatient. If the patient is to remain in the hospital for observation, the physician’s order is to keep the patient on outpatient status so that the patient can be monitored by the clinical staff. Typically, chest pain and syncope are symptoms that might require close monitoring while laboratory tests and radiologic examinations are performed and their findings reviewed. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) considers 48 hours to be the maximum amount of time that a patient would reasonably be held in observation status, at which point a decision to admit or to discharge should have been made. In exceptional circumstances, a patient might be held longer; however, the documentation should be very specific as to why the patient was held in observation for longer than 48 hours. If the patient is to be an inpatient, the physician should write the order to say: admit to inpatient status. The status of the patient is very important, because the billing and coding are different for inpatients and outpatients. In order to ensure that the patient’s status is clear, some hospitals use special forms for initial orders with the correct language embedded in the form. Similarly, in an electronic record, the patient status (inpatient vs. outpatient observation) would be a required field defined by menu. In recent years, whether a patient is an inpatient or given outpatient observation status has become a problematic issue for hospitals. The reimbursement for outpatient observation is minimal in comparison with that for inpatient admission. Short-stay inpatient admissions (length of stay 1 or 2 days) are targets of CMS auditors, who look to deny the admission for lack of medical necessity. In order to change the patient status from outpatient observation to inpatient admission, the physician writes a new order to admit to inpatient status. However, if a patient is admitted to inpatient status first and is later (during the admission) changed to outpatient observation status, a specific order must be written and the patient bill must contain a condition code 44 to reflect this action. Many hospitals post case management personnel in the emergency department or patient registration department in order to facilitate the placement of patients in the correct status and to liaise with physicians in the event of uncertainty as to the nature of a physician’s order. Hospitals often have an entire department whose function is similar to that of the registration or reception area of a physician’s office. The patient registration department (also called the admissions department or patient access department) is responsible for ensuring the timely and accurate registration of patients. Employees who perform the clerical function of completing the paperwork may be called admitting clerks, access clerks, registrars, or patient registration specialists. In a small hospital, the admissions department may consist of only one person; however, in a larger facility, dozens of health care professionals may be trained to register patients. If there is one place in the hospital where all registration activities are performed, the registration function is said to be centralized. In some facilities, the registration function may be decentralized—that is, registrars are placed in locations throughout the facility. For example, dedicated registration areas may be located in the emergency department, clinics, and ambulatory (same-day) surgery area. However registration is organized, it is a function that must be staffed around the clock, every day of the week. The patient registration staff must determine whether the patient has insurance and whether the insurance covers the care that the physician has requested. The attending physician must provide an admitting diagnosis to explain the reason for admission and a list of any planned procedures as part of the preapproval process. This preapproval, or precertification/insurance verification, process is extremely important to the hospital. Without the confirmation that the insurance company will pay for the patient’s stay, the hospital is exposed to the risk of financial loss in the event that the patient is unable to pay for his or her treatment. When the patient’s hospitalization is planned, the patient completes the initial registration process and possibly some preadmission testing (e.g., laboratory test and radiology procedures) before the actual hospitalization. This process gives the patient registration department time to obtain the necessary information. The registration process can be complicated because the registrars must be able to handle any and all admission scenarios and must understand a variety of insurance rules. Because the registrar is often the first hospital staff member that patients and their families meet, providing excellent customer service is important for this professional. Many facilities require registrars to speak at least two languages, depending on the patient population served. In addition, facilities may subscribe to translation services or maintain a call list of employees who speak multiple languages. Many registration departments are staffed and managed by health information professionals. Registrars have their own professional association, the National Association of Healthcare Access Management (http://www.naham.org). The American Association of Healthcare Administrative Managers and the Healthcare Financial Management Association also serve patient registration constituents. After the patient arrives at the patient registration reception area, the registration clerk asks the patient for proof of identity and insurance, as well as demographic data, certain socioeconomic data, and financial data. These data are used to populate (or update) the master patient index. In a paper record, these data are printed together on a form known as a face sheet or an admission record (Table 4-1). In a paper record, it is important to file this form at the beginning of every health record so that the patient is clearly identified to everyone who uses it. Additional data collected at this point include whether the patient has an advance directive (a written document, like a living will, that specifies a patient’s wishes for his/her care) and the name of the patient’s primary care physician. TABLE 4-1 SAMPLE DATA INCLUDED IN AN ADMISSION RECORD OR FACE SHEET These are typical items that are included in an admission record. In addition to printing out the admission record, the admissions department also provides either an identification plate for stamping pages or labels to affix to the individual pages. Using the plate or labels, clinical personnel can identify every page in the record, front and back. If the hospital uses a bar code system, labels with the patient’s bar code are also provided. Bar codes represent data in a way easily readable by a machine. Some systems allow the printing of forms with the patient’s identification data and bar code preprinted on them. The patient is also asked to sign an admission or general consent form, with the patient’s signature witnessed by the registration clerk. If the patient or the patient’s representative is unable to sign this form, the registrar must make a note of this fact and follow up with an attempt to obtain a signature during the hospitalization. In some cases, if the patient is unconscious or not of legal age, an alternative signature is obtained from a parent, guardian, or spouse. The general consent form also contains several key permissions that the patient grants to the facility, as follows: Consent for invasive procedures, such as surgical procedures, requires additional consent, as discussed later in this chapter. The general consent form also contains acknowledgements that the patient has received certain notifications, such as the notice of patients’ rights. In addition to beginning the data collection process for the health record and labeling the documents (if required), the registrar must also properly label the patients themselves. Typically, facilities use wristbands to identify each patient. These bands might include the patient’s name, birth date, admission date, medical record number (MR#), patient account number, account number, the bar code from admission, and the attending physician’s name (Figure 4-1). Recent technology has enabled a picture of the patient to be included on the wristband as well. Once the wristband is donned, it is difficult to remove so that the patient can be clearly identified from it during the hospitalization or encounter at all times. Physicians and all hospital staff must check each patient’s wristband before administering any treatments to confirm that they are performing the appropriate treatment for the right patient. Occasionally, the facility requires that patients be photographed for the purpose of identification. If photographs are taken, care must be taken to comply with all applicable rules to ensure patient privacy. As mentioned earlier, an acute care hospital has an emergency department. Patients arriving in the emergency department are initially treated as ambulatory care patients because they are expected to be treated and released. Sometimes, however, the condition of the patient warrants admission to the hospital or placement in observation. In this case, a member of the emergency department staff contacts the patient registration department to arrange for the change in status and for the patient to be transported from the emergency department to a bed on a patient unit. The patient registration department changes the patient’s status in the registration system, and an inpatient or observation stay is initiated. Clinical information accompanies the patient to the patient unit. Seriously ill patients may not be able to walk to the patient registration area or to provide required data. Therefore additional data collection often takes place at the patient’s bedside or with the assistance of family members. Although it is often the emergency department physician who identifies the need to observe or admit the patient, that physician generally does not write the order to do so. The emergency department physician typically contacts a staff physician, an on-call physician, or the patient’s primary care physician to discuss the patient’s condition and to issue the order. The physician who issues the order to observe or admit the patient is termed the admitting physician. The physician who directs the care given to the patient while hospitalized is termed the attending physician. The admitting physician can be different from the attending physician. For example, an on-call or staff physician may admit a patient with chest pain. The patient’s cardiologist may then take over the case and become the attending physician. After being formally admitted, the patient is taken to the appropriate treatment area. This area may be a patient unit, or sometimes it is the preoperative area, where the patient is prepared immediately for surgery. In the treatment area, the patient is assessed by nursing staff to determine the patient’s needs during care and obtain vital signs. The physician also performs an assessment of the patient in the SOAP structure discussed in Chapter 2. On the basis of the initial assessments, a plan of care is developed for the patient. Because the plan of care may involve many disciplines, often each patient is assigned to a patient care team that consists of various health care professionals in addition to physicians. The initial plan may consist of tests and other diagnostic procedures. A patient admitted for abdominal pain, etiology unknown, will undergo blood tests and possibly an ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan to determine the cause of the pain. Once a definitive diagnosis has been established, therapeutic procedures, such as surgery, may take place. For example, it may already have been determined that a patient has appendicitis and the patient has been admitted for an appendectomy. All procedures, whether diagnostic or therapeutic, are undertaken only on the direct order of the physician. Orders may also specify whether the patient has bathroom privileges, may ambulate independently, requires a special diet, or can have visitors. Other disciplines involved in the care of the patient include nurses and may include but are not limited to: social workers, psychologists, nutritionists, physical and occupational therapists, and respiratory therapists. In the acute care setting, these health care professionals are directed by the physician. In other words, they collaborate in developing and implementing the plan of care but cannot independently direct patient care. Some clinical personnel, such as physicians assistants, midwives, and advanced practice registered nurses, may be licensed as independent practitioners and may, through the hospital’s credentialing process, be approved to direct specific, limited types of patient care independently of a physician. In other cases, they may be dependent practitioners, directing patient care under the auspices of a particular physician. Although physicians direct patient care and are responsible for the overall plan, they are not always present with the patient during the inpatient stay. They may have office hours elsewhere or admit patients to multiple facilities. Some exceptions to this situation are hospitalists, who spend most of their time on the hospital premises, and intensivists, who focus their efforts on patients in critical care units. In some cases, the physician is not present at all and care is directed long distance (called telemedicine). In such cases, the physicians rely on nursing staff to advise them of changes in the patient’s status or problems that may arise. Nursing practice has evolved its own standards of practice, and nurses are diligent in documenting patient care and the events surrounding care. Because nurses spend far more time with a patient than the attending physician, nurse feedback is important to the physician’s medical decision making. Data continues to be collected and assessed throughout the patient’s stay. The utilization review (UR) or case management personnel monitor the patient’s care and facilitate the discharge of the patient to the appropriate setting. Discharge, like admission, is preceded by a physician’s order. Physicians, nurses, therapists, and numerous ancillary and administrative departments contribute a wide variety of notes, reports, and documentation of events. As discussed in Chapter 2, such documentation consists of collections of data organized in a logical manner into forms or data entry screens that build the health record. This section covers the major data elements that each of these professionals contributes and the traditionally named form into which the data are collected. Figure 4-2 shows the contributors of health data and the collections of data that they contribute. The primary purpose of the clinical data is communication. The communication is certainly among clinicians before, during, and after the specific episode of care. It is also part of the business record of the hospital and therefore supports both the legal record of the care rendered as well as the documentation of the charges for that care. Therefore accurate, complete documentation is essential for multiple reasons. When the patient is admitted, the attending physician conducts a medical evaluation. This SOAP-structured evaluation contains the subjective history, the objective physical examination, the assessment of a preliminary diagnosis or diagnoses, and a plan of care, for which orders are recorded. Medical decision making is a complex activity that depends on the number of possible diagnoses, the volume and complexity of diagnostic data that must be reviewed, and the severity of the patient’s condition. This complexity is reflected in the physician’s documentation. Figure 4-3 illustrates the components of medical decision making.

Acute Care Records

Chapter Objectives

Vocabulary

Clinical Flow of Data

The Order to Admit

The Patient Registration Department

Precertification

Registration Process

DATA ELEMENT

EXPLANATION

Patient’s identification number

Number assigned by the facility to this patient

Patient’s billing number

Number assigned by the facility to this visit

Admission date

Calendar day: month, day, and year

Discharge date

Calendar day: month, day, and year

Patient’s name

Full name, including any titles (MD, PhD)

Patient’s address

Address of usual residence

Gender

Male or female

Marital status

Married, single, divorced, separated

Race and ethnicity

Must choose from choices given on the admissions form

Religion

Optional

Occupation

General occupation (e.g., teacher, lawyer)

Current employment

Specific job (e.g., professor, district attorney)

Employer

Company name

Insurance

Insurance company name and address

Insurance identification numbers

Insurance company group and individual identification numbers

Additional insurance

Some patients are insured by multiple companies; all information must be collected

Guarantor

Individual or organization responsible for paying the bill if the insurance company declines payment

Attending physician

Name of the attending physician; may also include the physician’s identification number

Admitting diagnosis

Reason the patient is being admitted

Initial Assessment

Plan of Care

Discharge

Clinical Data

Physicians

Acute Care Records

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access