Theris A. Touhy

Nutrition and hydration

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

“If I do reach the point when I can no longer feed myself, I hope that the hands holding my fork belong to someone who has a feeling for who I am. I hope my helper will remember what she learns about me and that her awareness of me will grow from one encounter to another. Why should this make a difference? Yet, I am certain that my experience of needing to be fed will be altered if it occurs in the context of my being known . . . I will want to know about the lives of the people I rely on, especially the one who holds my fork for me. If she would talk to me, if we could laugh together, I might even forget the chagrin of my useless hands. We could have a conversation rather than a feeding.”

From Lustbader W: Thoughts on the meaning of frailty, Generations 13(4):21-22, 1999.

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Discuss nutritional requirements and factors affecting nutrition for older adults.

• Describe a nutritional screening and assessment.

• Identify interventions to promote adequate nutrition and hydration for older adults.

• Discuss assessment and interventions for older adults with dysphagia.

• List interventions that promote good oral hygiene for older adults.

Glossary

Chemosenses The senses of taste and smell.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) Backward flow of stomach contents into the esophagus.

Presbyesophagus Age-related change in the esophagus affecting motility.

Xerostomia Dry mouth

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

Nutrition

Adequate nutrition is critical to preserving the health of older people. The quality and quantity of diet are important factors in preventing, delaying onset, and managing chronic illnesses associated with aging (American Dietetic Association [ADA], American Society for Nutrition [ASN], Society for Nutrition Education [SNE], 2010). About 87% of older adults have diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or a combination of these diseases that may have dietary implications. (ADA, ASN, SNE, 2010). This chapter discusses the dietary needs of older adults, age-related changes affecting nutrition, risk factors contributing to inadequate nutrition and hydration, obesity, and the effect of diseases and functional and cognitive impairments on nutrition. Dysphagia and oral care are included as additional concerns related to adequate nutrition in older adults. Readers are referred to a nutrition text for more comprehensive information on nutrition and aging and disease.

The 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, an evidence-based nutritional guideline published by the federal government, is designed to promote health, reduce the risk of chronic diseases, and reduce the prevalence of overweight and obesity through improved nutrition and physical activity (www.dietaryguidelines.gov). The guidelines focus on balancing calories with physical activity and encourage Americans to consume more healthy foods like vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fat-free and low-fat dairy products, and seafood, and to consume less sodium, saturated and trans fats, added sugars, and refined grains. In addition to the key recommendations, there are recommendations for specific population groups including older adults (U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2012). Healthy People 2020 also provides goals for nutrition (see the Healthy People box).

Age-related requirements

Myplate for older adults

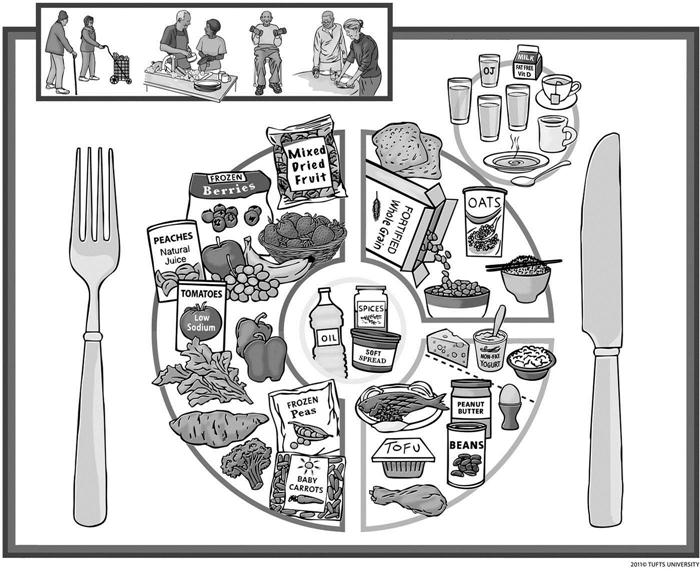

As part of the 2010 Guidelines, the new visual depiction of daily food intake, Choose MyPlate (ChooseMyPlate.gov), replaces the information formerly found on MyPyramid.gov. The USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University has introduced the MyPlate for Older Adults that calls attention to the unique nutritional and physical activity needs associated with advancing years. The drawing features different forms of vegetables and fruits that are convenient, affordable, and readily available. Other unique components of the MyPlate for Older Adults include icons for regular physical activity and emphasis on adequate fluid intake, areas of particular concern for older adults (Figure 9-1).

Generally, older adults need fewer calories because they may not be as active and metabolic rates slow down. However, they still require the same or higher levels of nutrients for optimal health outcomes. The recommendations may need modification for the older adult with illness. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) eating plan is another highly recommended eating plan to assist older adults with maintenance of optimal weight and management of hypertension. This plan consists of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, poultry, and fish, and restriction of salt intake. Information on DASH can be found at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/dash/.

Other dietary recommendations

Fats

Similar to other age groups, older adults should limit intake of saturated fat and trans fatty acids. High fat diets cause obesity and increase the risk of heart disease and cancer. Recommendations are that 20% to 35% of total calories should be from fat, 45% to 65% from carbohydrates, and 10% to 35% from proteins. Monounsaturated fats, such as olive oil, are the best type of fat since they lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but leave the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) intact or even slightly raise it.

Protein

Presently, the Institute of Medicine’s Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for protein of 0.8 g/kg per day, based primarily on studies in younger men, may be inadequate for older adults. Results of a recent study (Beasley et al., 2010) suggest that higher protein consumption, as a fraction of total caloric intake, is associated with a decline in risk of frailty in older adults. Protein intake of 1.5 g/kg per day, or 20% to 25% of total calorie intake, may be more appropriate for older adults at risk of becoming frail. Older people who are ill are the most likely segment of society to experience protein deficiency. Those with limitations affecting their ability to shop, cook, and consume food are at risk for protein deficiency and malnutrition.

Fiber

Fiber is an important dietary component that some older people do not consume in sufficient quantities. After age 50, women should receive around 21 g of dietary fiber daily, and men should receive around 30 g daily. However, even small amounts of fiber are beneficial (Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2012). The benefits of fiber include the following: facilitates the absorption of water; helps control weight by delaying gastric emptying and providing a feeling of fullness; improves glucose tolerance by delaying movement of carbohydrate into the small intestine; prevents or reduces constipation by increasing the weight of the stool and shortening the transit time; helps prevent hemorrhoids and diverticulosis by decreasing pressure in the colon, shortening transit time, and increasing stool weight; reduces the risk of heart disease by binding with bile (which contains cholesterol) and causes its excretion; and protects against cancer.

It is better to get fiber from food rather than from fiber supplements such as Metamucil because supplements do not contain the essential nutrients found in high-fiber foods and their anticancer benefits are questionable. Ways to increase fiber intake include eating cooked dry beans, peas, and lentils; leaving skins on fruits and vegetables; eating whole fruit rather than drinking fruit juice; and eating whole-grain breads and cereals (National Institute on Aging, 2011). Those who have difficulty chewing could sprinkle oat bran on cereals or in soups, meat loaf, or casseroles. The quantity of bran depends on the individual, but generally, 1 to 2 tablespoons daily is sufficient. Individuals who have not used bran should begin with 1 teaspoon and progressively increase the quantity until the fiber intake is enough to accomplish its purpose. Fluid intake of 64 ounces daily is essential as well.

Vitamins and minerals

Older people who consume five servings of fruits and vegetables daily will obtain adequate intake of vitamins A, C, and E, and potassium. But, Americans of all ages eat less than half of the recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables (Haber, 2010). After 50 years of age, the stomach produces less gastric acid, which makes vitamin B12 absorption less efficient. Vitamin B12 deficiency is a common and underrecognized condition that is estimated to occur in 12% to 14% of community-dwelling older adults and up to 25% of those residing in institutional settings (Ahmed & Haboubi, 2010).

Atrophic gastritis and pernicious anemia are the most common causes of vitamin B12 deficiency. Although intake of this vitamin is generally adequate, older adults should increase their intake of the crystalline form of vitamin B12 from fortified foods such as whole-grain breakfast cereals. Use of proton pump inhibitors for more than 1 year, as well as histamine H2 receptor blockers, can lead to lower serum vitamin B12 levels by impairing absorption of the vitamin from food. Metformin, colchicine, and antibiotic and anticonvulsant agents may also increase the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency (Cadogan, 2010).

Calcium and vitamin D are essential for bone health and may prevent osteoporosis and decrease the risk of fracture. Chapter 18 discusses recommendations for calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Calcium is a difficult mineral to absorb, and some foods inhibit calcium absorption (e.g., spinach, green beans, peanuts, and summer squash) (Table 9-1). High levels of protein, sodium, or caffeine also cause more calcium to be excreted in the urine and should be avoided. For older adults with inadequate calcium intake from diet, supplemental calcium can be used.

TABLE 9-1

Calcium Content of Several Common Foods

| Food Item | Serving Size | Calcium (mg) |

| Plain yogurt, fat-free | 8 oz | 452 |

| American cheese | 2 oz | 312 |

| Yogurt with fruit (low fat or fat-free) | 8 oz | 345 |

| Milk | 8 oz | 300 |

| Orange juice, calcium-fortified | 8 oz | 350 |

| Dried figs | 10 figs | 269 |

| Cheese pizza | 1 slice | 240 |

| Ricotta cheese, part skim | 1/2 cup | 334 |

| Ice cream, soft serve | 4 oz | 103 |

| Spinach | 4 oz | 139 |

| Cooked soybeans | 1 cup | 298 |

From National Institutes of Health: Sources of calcium, Washington, DC. Available at www.nichd.nih.gov/milk.

Obesity (overnutrition)

Although most of the research on nutrition and older adults has centered on underweight and frailty, the increase in the prevalence of obesity in the general population, and in older adults, is getting increased attention. More than two thirds of all adults in the United States are overweight (BMI = 25 to 29.9) or obese (BMI ≥30), and the proportion of older adults who are obese has doubled in the past 30 years (Flicker et al., 2010). The obesity epidemic is occurring in parallel with the aging of the baby boomer generation. Adults over the age of 60 years are more likely to be obese than younger adults. Non-Hispanic black individuals have the highest rate (44.1%) followed by Mexican Americans (39.3%) and non-Hispanic whites (32.6%) (Ogden et al., 2012). Socioeconomic deprivation and lower levels of education have been linked to obesity.

Although there is strong evidence that obesity in younger people lessens life expectancy and has a negative effect on functionality and morbidity, it remains unclear whether overweight and obesity are predictors of mortality in older adults. In what has been termed the obesity paradox, for people who have survived to 70 years of age, mortality risk is lowest in those with a BMI classified as overweight (Felix, 2008, p. 36). Flicker and colleagues (2010) conclude that “BMI thresholds for overweight and obese are overly restrictive for older people. Overweight older people are not at greater mortality risk, and there is little evidence that dieting in this age group confers any benefit; these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that weight loss is harmful” (p. 239). For nursing home residents with severely decreased functional status, obesity may be regarded as a protective factor with regard to functionality and mortality (Kaiser et al., 2010).

At this time, maintaining weight in older persons seems to be a clinical recommendation, and any weight loss interventions in older persons must be “carefully considered on an individualized basis with special attention to the weight history and the medical conditions of each individual” (Bales & Buhr, 2008, p. 311). Maintaining a healthy weight throughout life can prevent many illnesses and functional limitations as a person grows older.

Malnutrition

Malnutrition is defined as “a state in which a deficiency, excess or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients causes adverse effects on body form, function, and clinical outcome” (Ahmed & Haboubi, 2010, p. 207). The rising incidence of malnutrition among older adults has been documented in acute care, long-term care, and the community. Between 16% and 30% of older adults are malnourished or at high risk, and about half of this population has protein levels consistent with malnutrition when they are admitted to hospitals (Duffy, 2010). Older adults in skilled nursing facilities and long-term nursing home residents also have a higher incidence of malnutrition. These figures are expected to rise dramatically in the next 30 years (Ahmed & Haboubi, 2010). Malnutrition among older people is clearly a serious challenge for health professionals in all settings.

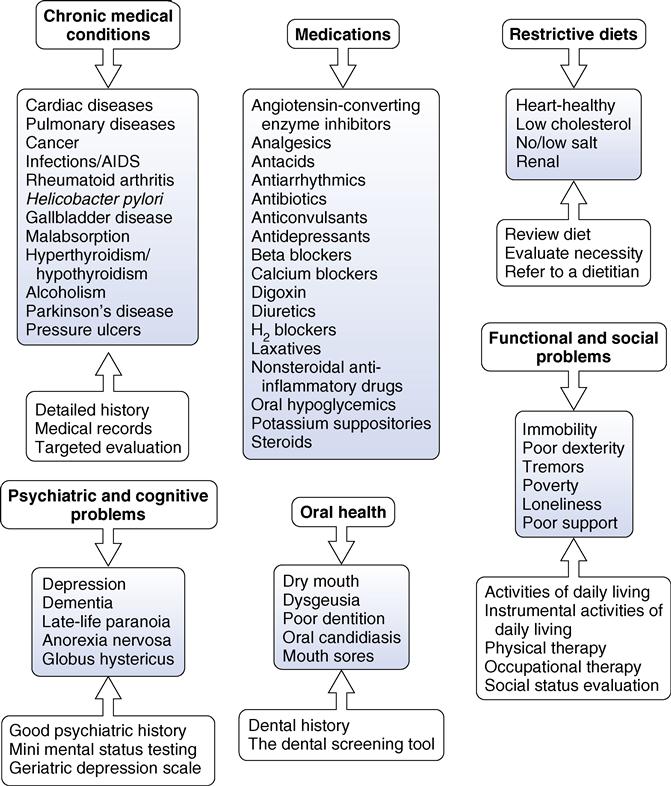

Malnutrition has serious consequences, including infections, pressure ulcers, anemia, hypotension, impaired cognition, hip fractures, and increased mortality and morbidity. “Malnourished older adults take 40% longer to recover from illness, have two to three times as many complications, and have hospital stays that are 90% longer” (Haber, 2010, p. 211). Many factors contribute to the occurrence of malnutrition in older adults (Figure 9-2).

Protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) is the most common form of malnutrition in older adults. PEM is characterized by the presence of clinical signs (muscle wasting, low BMI) and biochemical indicators (albumin, cholesterol, or other protein changes) indicative of insufficient intake. Signs and symptoms of PEM are nonspecific, and it is important that other conditions such as malignancy, hyperthyroidism, peptic ulcer, and liver disease are ruled out. Comprehensive nutritional screening and assessment are essential in identifying older adults at risk for nutrition problems or who are malnourished.

Factors affecting fulfillment of nutritional needs

Fulfillment of the older person’s nutritional needs is affected by numerous factors including changes associated with aging, lifelong eating habits, chronic disease, medication regimens, ethnicity and culture, socialization, socioeconomic deprivation, transportation, housing, and food knowledge.

Age-associated changes

Some age-related changes in the senses of taste and smell (chemosenses) and the digestive tract do occur as the individual ages and may affect nutrition. For most older people, these changes do not seriously interfere with eating, digestion, and the enjoyment of food. However, combined with other factors, they may contribute to inadequate nutrition and decreased eating pleasure (see Chapter 5).

Taste

The sense of taste has many components and primarily depends on receptor cells in the taste buds. Taste buds are scattered on the surface of the tongue, the cheek, the soft palate, the upper tip of the esophagus, and other parts of the mouth. Components in food stimulate taste buds during chewing and swallowing, and tongue movements enhance flavor sensation. Individuals have varied levels of taste sensitivity that seem predetermined by genetics and constitution, as well as age variations. Early studies suggested that a decline in the number of taste cells occurs with aging, but more recent studies suggest that “taste cells can regenerate but that the lag time of this turnover may account for the diminished taste response in older adults” (Miller, 2008, p. 363).

Age-related changes do not affect all taste sensations equally. With age, the inability to detect sweet taste seems to remain intact, whereas the ability to detect sour, salty, and bitter taste declines. Many denture wearers say they lose some of their satisfaction with food taste, possibly because dentures cover the palate and because texture is a very important element in food enjoyment. Difficulty in flavor appreciation comes from individual variables such as smoking, olfactory sensitivity, attitude toward food and eating, and the presence of moistening secretions. There are also aberrations in flavor sensation caused by certain medications and medical conditions. The addition of flavor enhancers (bouillon cubes) and concentrated flavors (jellies or sauces) can amplify both taste and smell. Fresh herbs and spices also give an extra boost to flavor and may increase enjoyment and interest in eating.

Smell

Age-related changes in the sense of smell and the consequent effect on nutrition is in need of further research. In the past, studies have shown a decline in the sense of smell as the individual ages. Research by Markovic and colleagues (2007) disputes this belief. Results of this study suggested that for perceived odors, olfactory pleasure increases at later stages in the life span, and the perceived intensity of odors remains stable. Decrease in the sense of smell may be related to many factors, including the following: nasal sinus disease, repeated injury to olfactory receptors through viral infections, age-related changes in central nervous system functioning, smoking, medications, and periodontal disease and other dentition problems. Changes in the sense of smell are also associated with Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease (Cacchione, 2008).

Digestive system

Age-related changes in the oral cavity, the esophagus, the stomach, the liver, the pancreas, the gallbladder, and the small and large intestines may influence nutritional status in concert with other factors. However, these changes do not significantly affect function, and, in the absence of disease, the digestive system remains adequate throughout life. Presbyesophagus, a decrease in the intensity of propulsive waves, may be an age-related change in the esophagus. Some of these changes may be more attributable to pathological conditions rather than to age alone. The functional impact of presbyesophagus seems to be minimal, but combined with other conditions, may contribute to dysphagia.

Buccal cavity

Age-related changes in the buccal cavity predispose older people to orodental problems that can significantly affect nutrition. Aging teeth become worn and darker in color and tend to develop longitudinal cracks. The dentin, or the layer beneath the enamel, becomes brittle and thickens so that pulp space decreases. People who are edentulous and are using complete dentures, continue to have oral health care needs. Ill-fitting dentures affect chewing and hence nutritional intake. People without teeth remain susceptible to oral cancer and other oral diseases. Oral care is discussed later in the chapter.

Another common oral problem among older adults is dry mouth (xerostomia). Approximately 25% to 40% of older adults experience xerostomia. More than 500 medications have the side effect of reducing salivary flow. A reduction in saliva and a dry mouth make eating, swallowing, and speaking difficult. It can also lead to significant problems of the teeth and their supporting structure (Jablonski, 2010). Artificial saliva preparations are available (avoid those containing sorbitol), and adequate fluid intake is also important when xerostomia occurs. Chewing on xylitol-flavored fluoride tablets, sugar-free candies, or sugar-free gum with xylitol 15 minutes after meals may stimulate saliva flow and promote oral hygiene (Miller, 2008). Medication review is also indicated to eliminate, if possible, medications contributing to xerostomia.

Regulation of appetite

Appetite in persons of all ages is influenced by factors such as physical activity, functional limitations, smell, taste, mood, socialization, and comfort. With age, appetite and food consumption decline. Healthy older people are less hungry and are fuller before meals, consume smaller meals, eat more slowly, have fewer snacks between meals, and become satiated after meals more rapidly than younger people (Ahmed & Haboubi, 2010). There is some evidence that the endogenous opioid feeding and drinking drive may decline in aging and contribute to decreased appetite and risk for dehydration.

Lifelong eating habits

The nutritional state of a person reflects the individual’s dietary history and present food practices. Lifelong eating habits are also developed out of tradition, ethnicity, and religion, all of which collectively can be called culture. Food habits established since childhood may influence the intake of older adults.

Eating habits do not always coincide with fulfillment of nutritional needs. Rigidity of food habits may increase with age as familiar food patterns are sought. Ethnicity determines if traditional foods are preserved, whereas religion affects the choice of foods possible. Members of a particular ethnic or religious group will have unique eating patterns, so individual assessment is important. Cultural preferences affect nutrition and culturally and religiously appropriate diets should be available in any institution or congregate dining program (see Chapter 4).

Lifelong habits of dieting or eating fad foods also echo through the later years. Older people may fall prey to advertisements that claim specific foods maintain youth and vitality or rid one of chronic conditions. Everyone can benefit from improved eating habits, and it’s never too late to change dietary habits to improve health. Following the MyPlate for Older Adults (see Figure 9-1) is best for an ideal diet, with changes based on particular problems, such as hypercholesteremia. Older adults should be counseled to base their dietary decisions on valid research and consultation with their primary care provider. For the healthy older adult, essential nutrients should be obtained from food sources rather than relying on dietary supplements.

Socialization

The fundamentally social aspect of eating has to do with sharing and the feeling of belonging that it provides. All of us use food as a means of giving and receiving love, friendship, or belonging. Often, older adults may be isolated from the mainstream of life because of chronic illness, depression, and other functional limitations. When one eats alone, the outcome is often either overindulgence or disinterest in food. The presence of others during meals is a significant predictor of caloric intake (Locher et al., 2008).

Disinterest in food may also result from the effects of medication or disease processes. Misuse and abuse of alcohol are prevalent among older adults and are growing public health concerns. Excessive drinking interferes with nutrition. Drinking alcohol depletes the body of necessary nutrients and often replaces meals, thus making an individual susceptible to malnutrition (see Chapter 22).

The elderly nutrition program, authorized under Title III of the Older Americans Act (OAA), is the largest national food and nutrition program specifically for older adults. Programs and services include congregate nutrition programs, home-delivered nutrition services (Meals-on-Wheels), and nutrition screening and education. The program is not means-tested, and participants may make voluntary confidential contributions for meals. However, the OAA Nutrition Program reaches less than one third of older adults in need of its program and services, and those served receive only three meals a week. With the emphasis on community-based care rather than institutional care, expansion of nutrition services should be a priority. These programs enable older adults to avoid or delay costly institutionalization and allow them to stay in their homes and communities (ADA, 2010).

Chronic diseases and conditions

Many chronic diseases and their sequelae pose nutritional challenges for older adults. Functional impairments associated with chronic disease interfere with the person’s abilities to shop, cook, and eat independently. For example, heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are associated with fatigue, increased energy expenditure, and decreased appetite. Dietary interventions for diabetes are essential but may also affect customary eating patterns and require lifestyle changes.

The side effects of medications prescribed for these conditions may further impair nutritional status. A number of prevalent disorders of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are associated with nutritional concerns including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), ulcers, constipation, diverticulosis, and colon cancer. Dysphagia, often a result of stroke or dementia, significantly affects nutrition. Diseases affecting function, such as arthritis and Parkinson’s disease, may impair eating ability. Cancers and subsequent treatment impair appetite and ability to consume adequate nutrition.

Many medications affect appetite and nutrition. These include digoxin, theophylline, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), iron supplements, antidepressants, and psychotropics. There are clinically significant drug-nutrient interactions that result in nutrient loss, and evidence is accumulating that shows the use of nutritional supplements may counteract these possible drug-induced nutrient depletions. A thorough medication review is an essential component of nutritional assessment and individuals should receive education about the effects of prescription medications, as well as herbals and supplements, on nutritional status (see Chapter 8).

Socioeconomic deprivation

There is a strong relationship between poor nutrition and socioeconomic deprivation. According to the federal government, fewer than 1 in 10 adults age 65 and older is living in poverty. However, poverty rates among older African Americans are nearly triple those of whites, and rates among Hispanics are more than double those of whites (Butrica, 2008). Older single women are also at high risk for poverty. Older adults with low incomes may need to choose among fulfilling needs such as food, heat, telephone bills, medications, and health care visits. Some older people eat only once per day in an attempt to make their income last through the month. Nurses need to be aware of resources in the community for socioeconomically disadvantaged older people and the local Area Agencies on Aging are good resources.

Transportation

Available and easily accessible transportation may be limited for older people. Many small, long-standing neighborhood food stores have been closed in the wake of the expansion of larger supermarkets, which are located in areas that serve a greater segment of the population. It may become difficult to walk to the market, to reach it by public transportation, or to carry a bag of groceries while using a cane or walker. Functional impairments also make the use of public transportation difficult for some older people.

Transportation by taxicab for an individual on a limited income is unrealistic, but sharing a taxicab with others who also need to shop may enable the older person to go where food prices are cheaper and to take advantage of sale items. Senior citizen organizations in many parts of the United States have been helpful in providing older adults with van service to shopping areas. In housing complexes, it may be possible to schedule group trips to the supermarket. Many urban communities have multiple sources of transportation available, but the older adult may be unaware of them. Resources in rural areas are more limited. It is important for nurses to be knowledgeable about resources in the community that are available to older people.

In addition, many older adults, particularly widowed men, may have never learned to shop and prepare food. Often, older adults have to rely on others to shop for them, and this may be a cause of concern depending on availability of support and the reluctance to be dependent on someone else, particularly family. For older adults who own a computer, shopping over the Internet and having groceries delivered offers advantages, although prices may be higher than in the stores.

Hospitalization and long-term care residence

Older adults in hospitals and long-term care settings are more likely to experience a number of the problems that contribute to inadequate nutrition. In addition to the risk factors mentioned earlier in the chapter, severely restricted diets, long periods of nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status, and insufficient time and staff for feeding assistance contribute to inadequate nutrition. Malnutrition is related to prolonged hospital stays, increased risk for poor health status, institutionalization, and mortality (DiMaria-Ghalili, 2012). Assessment of nutritional status to identify malnutrition and the risk factors for malnutrition is important and required by the Joint Commission. Sufficient time, care, and attention should be given to feeding dependent older people.

The incidence of eating disability in long-term care is high with estimates that 50% of all residents cannot eat independently (Burger et al., 2000). Inadequate staffing in long-term care facilities is associated with poor nutrition and hydration. In response to concerns about the lack of adequate assistance during mealtime in long-term care facilities, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented a rule that allows feeding assistants with 8 hours of approved training to help residents with eating. Feeding assistants must be supervised by a registered nurse (RN) or licensed practical–vocational nurse (LPN-LVN). Family members may also be willing and able to assist at mealtimes and also provide a familiar social context for the patient. Nurses need to provide guidance and support on feeding techniques, supervise eating, and evaluate outcomes.

For many older adults residing in long-term care facilities, the benefits of less-restrictive diets outweigh the risks. Restrictive diets (low salt, low cholesterol) often reduce food intake without significantly helping the clinical status of the individual (Pioneer Network and Rothschild Foundation, 2011). If caloric supplements are used, they should be administered at least 1 hour before meals or they interfere with meal intake. These products are widely used and can be costly. Often, they are not dispensed or consumed as ordered. Powdered breakfast drinks added to milk are an adequate substitute (Duffy, 2010).

Dispensing a small amount of calorically dense oral nutritional supplement (2 calories/mL) during the routine medication pass may have a greater effect on weight gain than a traditional supplement (1.06 calories/mL) with or between meals. Small volumes of nutrient-dense supplement may have less of an effect on appetite and will enhance food intake during meals and snacks. This delivery method allows nurses to observe and document consumption. Further studies and randomized clinical trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of nutritional supplementation (Doll-Shankaruk et al., 2008).

Attention to the environment in which meals are served is important. Feeding older people who have difficulty eating can become mechanical and devoid of feeling. The feeding process becomes rapid, and if it bogs down and becomes too slow, the meal may be ended abruptly, depending on the time the caregiver has allotted for feeding the person. Any pleasure derived through socialization and eating and any dignity that could be maintained is often absent (see “The Lived Experience” at the beginning of this chapter). Older adults accustomed to certain table manners may feel ashamed at their inability to behave in what they feel is an appropriate manner.

In addition to adequate staff, many innovative and evidence-based ideas can improve nutritional intake in institutions. Suggestions found in the literature include the following: restorative dining programs; homelike dining rooms; individualized menu choices, including ethnic foods; cafeteria style service; refreshment stations with easy access to juices, water, and healthy snacks; kitchens on the nursing units; availability of food around the clock; choice of mealtimes; liberal diets; finger foods; visually appealing pureed foods with texture and shape; music; touch; verbal cueing; hand-over-hand feeding; and sitting while assisting the person to eat. Other suggestions can be found in Box 9-1.