Community Health Education

Cathy D. Meade

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Describe the goals of health education within the community setting.

2. Examine the nurse’s role in community education within a sociopolitical and cultural context.

3. Select a learning theory, and describe its application to the individual, family, or aggregate.

6. Examine the importance of community engagement for having an impact on health disparities.

Key terms

cognitive theory

community empowerment

community-based participatory methods

culturally effective care

health disparities

health education

health literacy

humanistic theories

learner verification

learning

materials and media

participatory action research (PAR)

problem-solving education

social learning theory

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

Connecting with everyday realities

The nurse may be tempted to often ask the following questions:

• Why does she keep smoking when she is pregnant?

• Why does the senior not get a follow-up for his fecal occult blood test (FOBT) abnormality?

• Why does this young man not take his diabetic medications (insulin) each day?

• Why are the parents late in immunizing their kids?

• Why won’t more women attend the clinic’s breast cancer screenings—they’re free!

• Why does the community have such an alarming rate of obesity?

Although these questions represent the nurse’s intense desire to understand the link between health behavior and health education, they do not yield answers or empower individuals or families. In fact, such questions do not address the root health issues and create a “blaming the victim” approach (Israel et al., 1994). The nurse might reframe the previous questions to better get at the root reasons and, in turn, empower individuals, families, and groups. Instead, ask the following questions:

Health education in the community

Historically, teaching has been a significant nursing responsibility since Florence Nightingale’s (1859) early work. Gardner (1936) emphasized that health teaching is one of the most fundamental nursing principles and that “a nurse, in even the most obscure position must be a teacher of no mean order.” There is much support for the nurse’s involvement in health education, including the nurse practice acts, professional statements of the American Nurses Association (ANA) (1975), the patient’s bill of rights of the American Hospital Association (AHA) (1975), the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (now the Joint Commission, 1995), national standards on culturally and linguistically appropriate services of the Office of Minority Health (OMH) (1999), and the Healthy People 2020 objectives of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) (2000) (see proposed communication objectives at www.healthypeople.gov/hp2020/Objectives/TopicArea.aspx?id=25&TopicArea=Health+Communication+and+Health+IT). Health education is an integral part of the nurse’s role in the community for promoting health, preventing disease, and maintaining optimal wellness (Box 8-1). Moreover, the community is a vital link for the delivery of effective and equitable health care and offers the nurse multiple opportunities for providing appropriate health education within the context of a setting that is familiar to community members (Meade et al., 2002a).

The role of the nurse as health educator is especially important in light of the increasing diversity and demographically changing population in the United States, the increasingly technological advancements in health care, and the need to reduce the disconnect between scientific discovery and the delivery of interventions in the community (Freeman, 2004; Chu et al., 2008). More than ever before, health education activities and services are taking place outside the walls of hospitals in such settings as missions, YMCAs, beauty and barber shops, grocery stores, homeless shelters, community-based clinics, health maintenance organizations, schools, work sites, senior centers, mobile health units, homes, and Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) sites. At the core of health education is the development of trusting relationships based on nurturing interactions, the use of community-based participatory methods that highlight community strengths, and the creation of sustainable collaborations and partnerships (Gwede et al., 2009; Leung, Yen, and Minkler, 2004; Luque et al., 2010; Martinez et al., 2008; Meade et al., 2009; Minkler, 2005; Olshansky et al., 2005; Smedley et al., 2003).

Health education’s goal is to understand health behavior and to translate knowledge into relevant interventions and strategies for health enhancement, disease prevention, and chronic illness management. Health education aims to enhance wellness and decrease disability; attempts to actualize the health potential of individuals, families, communities, and society; and includes a broad and varied set of strategies aimed at influencing individuals within their social environment for improved health and well-being (Green and Kreuter, 2004). The nurse is ideally situated to bring together the necessary skills, knowledge, and community resources to impact the health of the community.

Health education is any combination of learning experiences designed to predispose, enable, and reinforce voluntary behavior conducive to health in individuals, groups, or communities (Green and Kreuter, 2004). Steuart and Kark (1962) state that “health education must achieve its ends through means that leave inviolate the rights of self-determination of the individuals and their community.” A major challenge for community health nurse educators is to address the complex and intersecting sociopolitical conditions that affect community health by placing value on the contributions of community members and building on their strengths. The lasting effect of cognitive and behavioral changes relies heavily on learner participation to influence change in health behaviors and practices (Green and Kreuter, 2004; Leung et al., 2004; MacLeod and Zimmer, 2005; Cashman et al., 2008; Wallerstein and Duran, 2006; Kannan et al., 2008). In this manner, nurses alone cannot set individual, family, or community priorities. Rather, learners (community members) must be involved in determining their health education needs and priorities.

Community health education is based on practical, relevant, and scientifically sound methods and widely accessible technology. In the late 1970s, Kleinman (1978) described a social and cultural community health care system that related external factors (e.g., economical, political, and epidemiological) to internal factors (e.g., behavioral and communicative). This view of a sociocultural health care system grounds health education activities within sociopolitical structures, especially within local environmental settings, and views the community as client (Coleman et al., 2009; Giachello et al., 2003; Horowitz et al., 2004; Kobetz et al., 2009; Martyn et al., 2009; Meade et al., 2007; Petersen et al., 2004; Villarruel et al., 2007). As such, because the community level is often the location of health prevention and health intervention programs, it is significant for obtaining positive health outcomes. Moreover, the creation and delivery of relevant health education interventions and communications within the community setting is a national imperative as outlined by Healthy People 2020, OMH’s Standards for the Provision of Culturally Competent Health Care (1999), and several Institute of Medicine reports (e.g., Nielsen-Bohlman et al., 2004; Smedley et al., 2003). Nurses are uniquely qualified to influence the health and well-being of community members’ health behaviors through original and inventive activities that incorporate culturally, linguistically, and educationally relevant health education and outreach communications (Meade et al., 2007; Watters, 2003).

Learning theories, principles, and health education models

Learning Theories

Learning theories are helpful in understanding how individuals, families, and groups learn. The field of psychology provides the basis for these theories and illustrates how environmental stimuli elicit specific responses. Such theories can aid nurses to recognize the mechanisms that potentially modify knowledge, attitude, and behavior. Bigge and Shermis (2004) assert that learning is an enduring change that involves the modification of insights, behaviors, perceptions, or motivations. Although psychology textbooks describe learning theories in great detail, the following broad categories relate to the nursing application in a community setting: stimulus-response (S-R) conditioning (i.e., behavioristic), cognitive, humanistic, and social learning. Resource Tool 8A  Learning Theories and Their Relationship to Health Education on the book’s Evolve website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Nies outlines these learning theories.

Learning Theories and Their Relationship to Health Education on the book’s Evolve website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Nies outlines these learning theories.

The nurse should remember that theories are not completely right or wrong. Different theories work well in different situations. Knowles (1989) relates that behaviorists program individuals through S-R mechanisms to behave in a certain fashion. Humanistic theories help individuals develop their potential in self-directing and holistic manners. Cognitive theorists recognize the brain’s ability to think, feel, learn, and solve problems and train the brain to maximize these functions. Although social learning theory is largely a cognitive theory, it also includes elements of behaviorism (Bandura, 1977b). Social learning theory’s premise is based on behavior explaining and enhancing learning through the concepts of efficacy, outcome expectation, and incentives

.

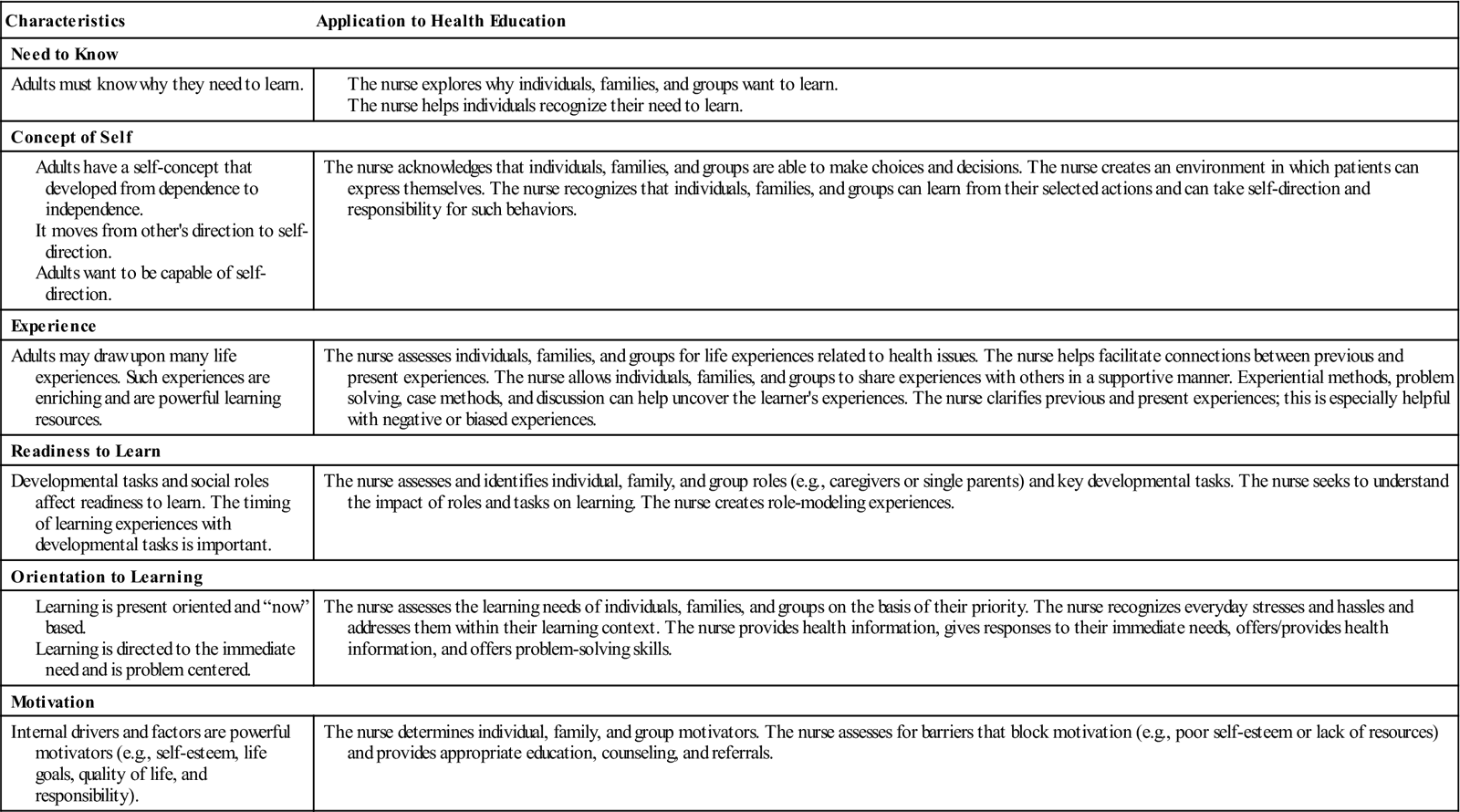

Knowles’ Assumptions About Adult Learners

Knowles (1988, 1989) outlined several assumptions about adult learners. He contends that adults, like children, learn better in a facilitative, nonrestrictive, and nonstructured environment. Nurses who are familiar with these assumptions can develop teaching strategies that motivate and interest individuals, families, and groups and encourage active and full participation in the learning process. Nurses can help to create a self-directing, self-empowering learning environment. The following characteristics impact learning: the client’s need to know, concept of self, readiness to learn, orientation to learning, experience, and motivation. Table 8-1 expands on these characteristics.

TABLE 8-1

Characteristics of Adult Learners

Modified from Knowles MS: The making of an adult educator: an autobiographical journey, San Francisco, 1989, Jossey-Bass; and Knowles MS: The modern practice of adult education: from pedagogy to andragogy, Chicago, 1988, Cambridge Press.

Health Education Models

In addition to learning theories, applying education theories and principles to situations involving individuals, families, and groups illustrates how ideas fit together, offers explanations for health behaviors or actions, and helps direct community nursing interventions. Such theoretical elements form the basis of understanding health behavior. Glanz and colleagues (2008) state that theories give educators the power to assess an intervention’s strength and impact, and they serve to enrich, inform, and complement practice. Theoretical frameworks offer nurses an intervention blueprint that promotes learning and provides them with an organized approach to explaining concept relationships (Padilla and Bulcavage, 1991).

What the nurse needs is often not a single theory that would explain all that he or she hears, but rather a framework with meaningful hooks and rubrics on which to hang the new variables and insights offered by different theories. With this customized metatheory or framework, the nurse can triage new ideas into categories that have personal utility in his or her practice and everyday realities. (Green, 1998, p. 2)

Models of Individual Behavior

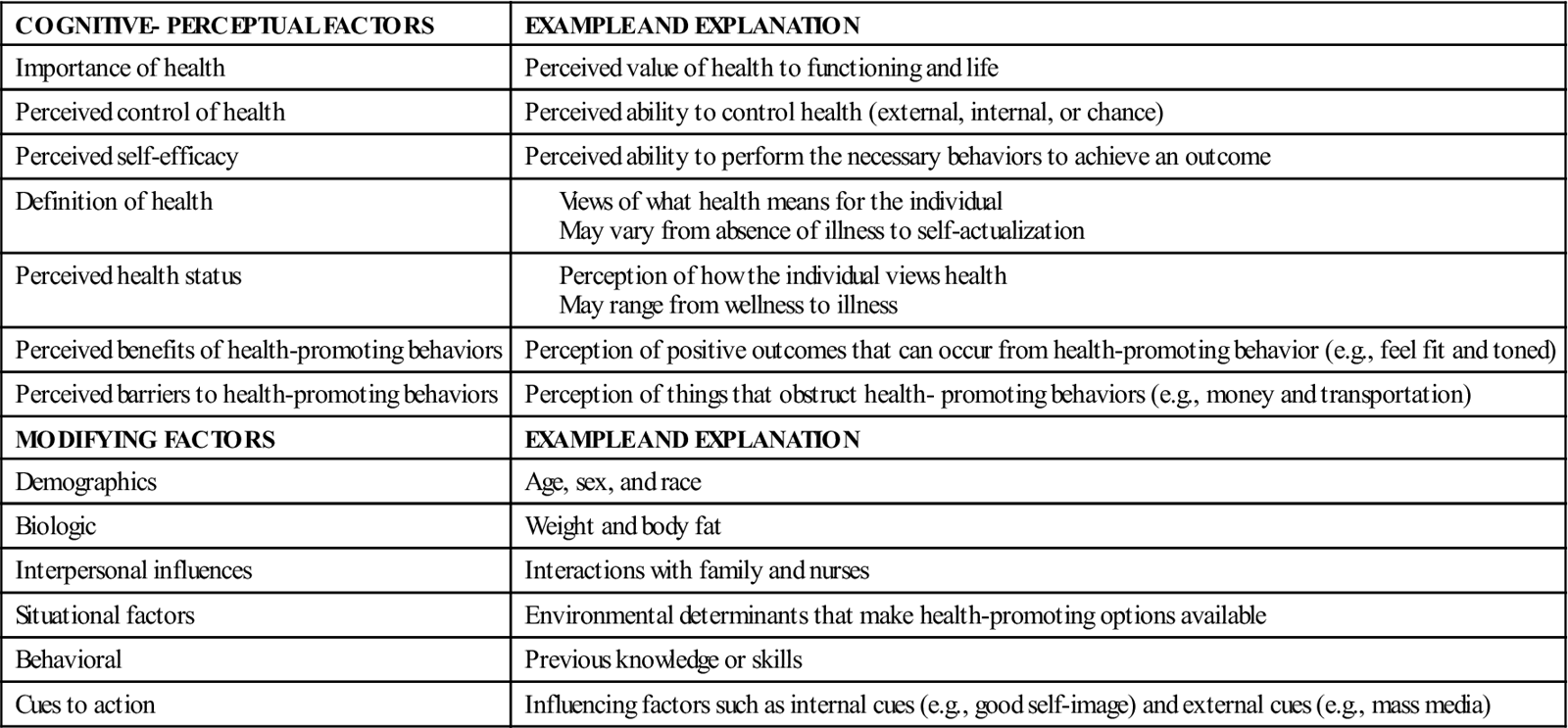

Two models that explain preventive behavior determinants are the Health Belief Model (HBM), which is presented in Table 8-2 (Becker et al., 1977; Hochbaum, 1958; Kegeles et al., 1965; Rosenstock, 1966), and the Health Promotion Model (HPM) (Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons, 2005). Both models are multifactorial, are based on value expectancy, and address individual perceptions, modifying factors, and likelihood of action. The HBM is based on social psychology and has undergone much empirical testing to predict compliance on singular preventive measures. The initial purpose of the HBM was to explain why people did not participate in health education programs to prevent or detect disease, in particular, tuberculosis (TB) screening programs (Hochbaum, 1958). Subsequent studies addressed other preventive actions and factors related to adherence to medical regimens (Becker, 1974). Primarily, the HBM is a value expectancy theory that addresses factors that promote health-enhancing behavior. It is disease specific and focuses on avoidance orientation. The HBM considers perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and other sociopsychological and structural variables. In an early review of 46 studies using the HBM, perceived benefits were found to be the most powerful predictive element within the model, whereas perceived severity had the lowest associative value (Janz and Becker, 1984). Self-efficacy, or the notion that an individual can act successfully on a given behavior to produce the desired outcome (Bandura, 1977a, 1977b), was later added to the HBM (Rosenstock, Strecher, and Becker, 1988; Strecher et al., 1986).

TABLE 8-2

| Components | Example and Explanation |

| Perceived susceptibility | Belief that disease state is present or likely to occur |

| Perceived severity | Perception that disease state or condition is harmful and has serious consequences |

| Perceived benefits | Belief that health action is of value and has efficacy |

| Perceived barriers | Belief that health action would be associated with hindrances (e.g., cost) |

| Self-efficacy | Belief that actions can be performed to achieve the desired outcome (one’s confidence) |

| Demographics | Age, sex, and ethnicity |

| Cues to action | Influencing factors to get ready for action (e.g., billboards, reminder cues, newspapers) |

For a more detailed description of the HBM, see Becker (1974).

Champion and Skinner (2008) point out that one of the limitations of the HBM is the variability in measurement of the central HBM constructs, which include the inconsistent measurement of HBM concepts and the lack of establishing validity and reliability of the measures prior to testing. For example, applying similar construct measures across different behaviors, such as barriers for mammography and colonoscopy, may be quite different. Although the past decade has produced some good examples of HBM scale development (Champion, 1999; Champion et al., 2008; Joseph et al., 2007; Rawl et al., 2000), caution should be taken when applying the HBM in multicultural settings. It would be important to determine whether the overall assumptions of the HBM—assumptions related to the value of health and illness—are similar to those of the particular racial/ethnic group under study. Further, checking wording for cultural distinctions is critical to the model’s usefulness (Janz, Champion, and Strecher, 2002). Although the HBM identifies an array of variables important in explaining individual health, nurses should view these variables within a larger societal perspective.

Pender’s Health Promotion Model (HPM) is a competence or approach-oriented model and, unlike the HBM, does not rely on personal threat as a motivating factor. The HPM brings together a number of constructs from expectancy-value theory and social cognitive theory within a holistic nursing framework (Pender et al., 2005). Gillis (1993) reviewed 23 studies conducted between 1983 and 1992 and reported that Pender’s HPM was the most common theoretical framework in health promotion studies. Gillis identified that self-efficacy was the strongest determinant of participation in a health-promoting lifestyle, followed by social support, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and an individual’s definition of health education. Locus of control was the least important determinant, although it is the most studied.

The HPM is meant to provide an organizing framework to explain why individuals engage in health actions. It is applicable across the lifespan and has been used to examine the multidimensional nature of persons interacting with their physical and interpersonal environments, such as bicycle helmet use (Lohse, 2003) or health-promoting behaviors among Hispanics (Hulme et al., 2003), as a causal model of commitment to a plan for exercise in a sample of 400 Korean adults (Shin et al., 2005), and use of hearing protection devices by 703 construction workers (Ronis, Hong, and Lusk, 2006). Table 8-3 lists the main HPM components with behavioral action as the desired output.

TABLE 8-3

Health Promotion Model Components and Outputs

For a more comprehensive description and explanation of the HPM, see Pender et al. (2005).

The HBM and HPM can assist community health nurses in examining an individual’s health choices and decisions for influencing health-related behaviors. The models offer nurses a cluster of variables that provide interesting insights into explaining health behavior. These variables are helpful cues; the nurse should consider them in planning and interacting with health education interventions but not try to fit an individual into all the categories. Simply put, models are aids that guide nurses in assessing patients and in developing, selecting, and implementing relevant educational interventions. In applying the models, a nurse might consider the following questions in relation to his or her own health behavior:

• Do you strive for improved health?

• Are you or your family susceptible to heart disease or obesity?

• Does a family history of cardiovascular disease motivate you or your family to exercise?

• Does looking fit and toned and having energy motivate you to exercise?

• Do work, school, or family responsibilities get in the way of your exercise plans?

• Do money, safety, and time pose barriers to planning an exercise program?

• Do you see any benefits to exercise, for example, looking and feeling better and more energized?

Think about these questions and consider your answers. Talk about these issues with a colleague and try to develop an action plan tailored to your own priorities, needs, and capabilities.

Model of Health Education Empowerment

The HBM and HPM focus on individual strategies for achieving optimal health and well-being. The models are similar in that they are multifactorial, are based on the idea of value expectancy, and address individual perceptions, modifying factors, and likelihood of action. Although such approaches may be appropriate in changing individual behaviors, they do not address the complex relationships among social, structural, and physical factors in the environment, such as racism, lack of social support systems, and inaccessible health services (Israel et al., 1998; Smedley et al., 2003). Van Wyk (1999) suggests that nurses cannot assign power and control to the individual within the community but rather that the “power” must be taken on by the individual with the nurse guiding the dynamic process. This process includes examining such factors as education, health literacy, gender, and class and recognizing the structural and foundational changes that are needed to elicit change for socially and politically disenfranchised groups. Thus, knowledge is produced in a social context, and it is inextricably bound to relations of power.

An appropriate health education model is one that embraces a broader definition of health and addresses social, political, and economic aspects of health. This view of the health care system as a sociocultural system better grounds health education interventions within the sociopolitical structure, especially within local environmental settings (Goodman et al., 1998; Labonte, 1994). Such a theoretical perspective is congruent with community health education because it supports learner participation and involvement and emphasizes empowerment.

Empowerment and literacy are two concepts that share a common history: The concept of empowerment can be traced back to Paulo Freire, a Brazilian educator in the 1950s who sought to promote literacy among the poorest of the poor, most oppressed members of the population. He based his work on a problem-solving approach to education, which contrasts with the banking education approach that places the learner in a passive role. Problem-solving education allows active participation and ongoing dialogue and encourages learners to be critical and reflective about health issues. Freire suggested that when individuals assume the role of objects, they become powerless and allow the environment to control them. However, when individuals become subjects, they influence environmental factors that affect their lives and community. Thus community members, or subjects, are the best resources to elicit change (Freire, 2000, 2005).

Freire’s methodology, often referred to as critical consciousness, involves not only education but also activism on the part of the educator. The basic tenet of Freire’s work centers on empowerment, the contextualization of peoples’ daily experiences, and collaborative, collegial dialogue in adult education. Freire’s work speaks to a variety of action research applications, including those that relate to improving community health of marginalized populations. Freire’s approach to health education increases health knowledge through a participatory group process and emphasizes establishing sustainable lateral relationships. This process explores the problem’s nature and addresses the problem’s deeper issues. The nurse, or facilitator-educator, is a resource person and is an equal partner with the other group members. Listening is the first phase and is essential to understanding the issues. The exchange of ideas and concerns creates a problem-posing dialogue and identifies root problems or generative themes. The group discusses and explores the problem’s root causes. Finally, group members create relevant action plans that are congruent with their own reality (Freire, 2000).

The goal of participatory action research (PAR) is social change. It is consistent with the role and responsibilities of the community nurse (Olshansky et al., 2005) and embraces the use of community-based participatory methods. What this means is that participation and action from stakeholders and important knowledge about conditions and issues gained facilitates strategies reached collectively (e.g., access to care, access to information). In this manner, the value of communities’ experiential knowledge is affirmed (Leung et al., 2004). Examples of the use of PAR include Horowitz et al. (2004), who describe the use of combining local and academic expertise to study health disparities and create peer-led classes to improve chronic disease management in East and Central Harlem; Edgren and colleagues (2005), who offered suggestions for involving the community in fighting against asthma; English and colleagues (2004), who developed the REACH 2010 program to build a public health community capacity program with a tribal community in the Southwest; and Giachello et al., (2003), who addressed the disproportionately high rate of diabetes in southeast Chicago through community-led activities.

At the core of empowerment are information, communication, and health education (World Health Organization [WHO], 1994). When nurses involve individuals, families, and groups in their learning, it validates their role and helps ensure the intervention’s relevance (Leung et al., 2004; Meade et al., 2003; Minkler, Wallerstein, and Wilson, 2008; Olshansky et al., 2005). Nurses can use empowerment strategies to help people develop skills in problem solving, critical thinking, networking, negotiating, lobbying, and information seeking to enhance health. Freire’s approach may seem similar to health education’s emphasis on helping people take responsibility for their health by providing them with information, skills, reinforcement, and support. However, Freire purports that knowledge imparted by the collective group is significantly more powerful than information provided by health educators. Freire’s approach attempts to uncover the social and political aspects of problems and encourages group members to define and develop action strategies. Hence, health changes are complex and usually do not have immediate solutions; therefore the term problem posing, rather than problem solving, may better describe this empowerment process (Minkler, Wallerstein, and Wilson, 2008).

Examples of Empowerment Education and Participatory Methods

1. López and colleagues (2005) relate how photovoice was used as a participatory action research method with African-American breast cancer survivors in rural east North Carolina, referred to as the “inspirational images project.” The aim of the study was to use this research method to allow women to convey the social and cultural meaning of silence about breast cancer and to voice their survivorship concerns so that relevant interventions could be developed to meet their needs. The task of the women was to take at least six pictures of people, places, or things that they enjoyed in life; significant things they encountered as a survivor; and what was used to cope. Discussion of photographs (e.g., picture of church) led to discussions including a six-step inductive questioning technique suggested by Wallerstein and Bernstein (1988), which helps participants in framing educational strategies:

• What do you SEE in this photograph?

• What is HAPPENING in the photograph?

• How does this relate to OUR lives?

• How can we become EMPOWERED by our new social understanding?

• What can we DO to address these issues?

The use of photovoice offers an important and creative way to facilitate shared knowledge to achieve social change.

2. N. Wilson and colleagues (2008) describe YES! (Youth Empowerment Strategies), an after-school program for underserved elementary and middle school youth. Designed to reduce risky behaviors including drug, alcohol, and tobacco use, YES! combines multiple youth empowerment strategies to bolster youth’s capacities and strengths to build problem-solving skills. A number of empowerment education projects including photovoice and social action projects (e.g., awareness campaigns, projects to improve school spirit) were developed that involved members of the intended audience in the planning and implementation.

3. Luque et al. (2010) report the use of empowering processes based on Freire’s Popular Education principles (Freire, 2000) and Social Cognitive Theory, which focused on the constructs of environment, behavioral capability, observational learning, and self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977a, 1977b) for creating a barbershop training program about prostate cancer. By employing techniques borrowed from empowerment education (Wallerstein and Bernstein, 1988), barbers were engaged in group learning activities and problem-posing exercises around preferences and values related to prostate cancer health. Once the training and curriculum was completed among eight barbers, the team worked closely with the barbers to modify and create a supportive workplace environment for new health education tools (easy-to-read posters, brochures, DVD player, prostate cancer display model) to fuel discussions about prostate cancer health and decision making. Once the barbers were trained, structured surveys with barbershop clients (N = 40) were conducted. Results showed a significant increase in participants’ self-reported knowledge of prostate cancer and an increased likelihood of discussing prostate cancer with a health care provider (P <.001). In conclusion, the barber-administered pilot intervention appears to be an appropriate and viable communication strategy for promoting prostate knowledge to a priority population in a convenient and familiar setting.

Community Empowerment

Community empowerment is a central tenet of community organization, whereby community members take on greater power to create change. It is based on community cultural strengths and assets. An empowerment continuum acknowledges the value and interdependence of individual and political action strategies aimed at the collective while maintaining the community organization as central (Minkler, Wallerstein, and Wilson, 2008). As such, community organization reinforces one of the field’s underlying premises as outlined by Nyswander (1956): “Start where the people are.” Meade and Calvo (2001) point out that attention must be given to collective rather than individual efforts to ensure that the outcomes reflect the voices of the community and truly make a difference in people’s lives. Further, Labonte (1994) states that the community is the engine of health promotion and a vehicle of empowerment. He describes five spheres of an empowerment model, which focus on the following levels of social organization: interpersonal (personal empowerment), intragroup (small-group development), intergroup (community), interorganizational (coalition building), and political action. A multilevel empowerment model allows us to consider both macro-level and micro-level forces that combine to create both health and disease. Therefore, it seems that both micro and macro viewpoints on health education provide nurses with multiple opportunities for intervention across a broad continuum.

In summary, health education activities that respond to McKinlay’s (1979) call to study “upstream,” that is, to examine the underlying causes of health inequalities, through multilevel education and research allow nurses to be informed by critical perspectives from education, anthropology, and public health. For more extensive readings on this topic, see Methods in Community-based Participatory Research for Health (Israel et al., 2005) and Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes (Minkler and Wallerstein, 2008).

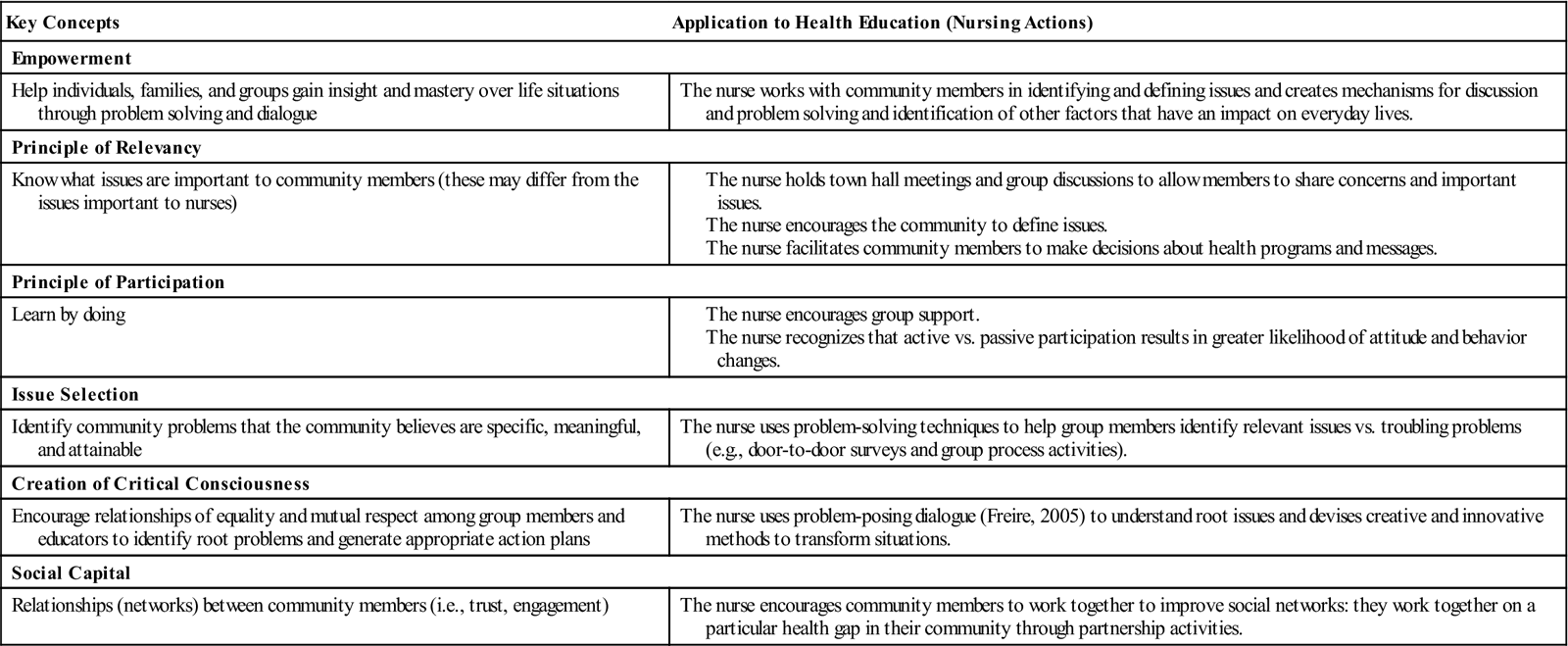

To effect change at the community level, nurses must be knowledgeable about key concepts central to community organization (Table 8-4). This approach is an effective methodological tool that enables nurses to partner with the community, identify common goals, develop strategies, and mobilize resources to increase community empowerment, capacity, and community competence. Key concepts inherent in community health education programming are empowerment, principle of participation, issue selection, principle of relevance, social capital, and creation of critical consciousness (Minkler, Wallerstein, and Wilson, 2008).

TABLE 8-4

Community Organization Practice

Modified from Minkler M, Wallerstein N, Wilson N: Improving health through community organization and community building. In Glanz K et al., editors: Health behavior and health education: theory, research and practice, ed 4, San Francisco, 2008, Jossey-Bass, pp. 288-312.

Keck (1994) indicated that successful community health relies on empowering citizens to make decisions about individual and community health. Empowering citizens causes power to shift from health providers to community members in addressing health priorities. Collaboration and cooperation among community members, academicians, clinicians, health agencies, and businesses help ensure that scientific advances, community needs, sociopolitical needs, and environmental needs converge in a humanistic manner. The development of LUNA (Latinas Unidas por un Nuevo Amanecer, Inc.) in Tampa, Florida, illustrates how the basic tenets of community need and organization fuel the development of a locally initiated group. LUNA represents a grassroots initiative to meet the needs of Hispanic breast cancer survivors and serves as a model for nurses, researchers, and community advocates working with underserved groups of cancer survivors

.

The nurse’s role in health education

Although learning theories and health education models provide a useful framework for planning health interventions, the nurse’s ability to facilitate the education process and become a partner with individuals and communities is key to the method’s application. At the core of health education is the therapeutic and healing relationship between the nurse and individuals, families, and the community. Simply put, nurses hold the process together and are catalysts for change in delivering humanistic care. Nurses activate ideas, offer appropriate interventions, identify resources, and facilitate group empowerment. Rankin and Stallings (2000) describe the following key characteristics of nurses in facilitating the teacher-learner process: confidence, competence, caring, and communication. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to describe multiple communication techniques in detail, but the reader is reminded about the value of establishing inclusion and trust before delivering the health education content

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree