Watson’s philosophy and theory of transpersonal caring

D. Elizabeth Jesse and Martha R. Alligood

“We are the light in institutional darkness, and in this model we get to return to the light of our humanity”

(Jean Watson, 7/9/2012.)

Jean Watson

1940 to Present

Credentials and background of the theorist

Margaret Jean Harman Watson, PhD, RN, AHN-BC, FAAN, was born and grew up in the small town of Welch, West Virginia, in the Appalachian Mountains. As the youngest of eight children, she was surrounded by an extended family–community environment.

Previous authors: Ruth M. Neil, Ann Marriner Tomey, Tracey J. F. Patton, Deborah A. Barnhart, Patricia M. Bennett, Beverly D. Porter, and Rebecca S. Sloan. These authors wish to thank Dr. Jean Watson for her ongoing inspiration and support, along with her review of the content of this chapter for accuracy and her assistance in updating the references and bibliography.

Watson attended high school in West Virginia and then the Lewis Gale School of Nursing in Roanoke, Virginia. After graduation in 1961, she married her husband, Douglas, and moved west to his native state of Colorado. Douglas, whom Watson describes as her physical and spiritual partner, and her best friend, died in 1998. She has two grown daughters, Jennifer and Julie, and five grandchildren. Jean lives in Boulder, Colorado.

After moving to Colorado, Watson continued her nursing education and graduate studies at the University of Colorado. She earned a baccalaureate degree in nursing in 1964 at the Boulder campus, a master’s degree in psychiatric–mental health nursing in 1966 at the Health Sciences campus, and a doctorate in educational psychology and counseling in 1973 at the Graduate School, Boulder campus. After Watson completed her doctoral degree, she joined the School of Nursing faculty, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver, where she has served in both faculty and administrative positions. In 1981 and 1982, she pursued international sabbatical studies in New Zealand, Australia, India, Thailand, and Taiwan; in 2005, she took a sabbatical for a walking pilgrimage in the Spanish El Camino.

In the 1980s, Watson and colleagues established the Center for Human Caring at the University of Colorado, the nation’s first interdisciplinary center committed to using human caring knowledge for clinical practice, scholarship, and administration and leadership (Watson, 1986). At the center, Watson and others sponsor clinical, educational, and community scholarship activities and projects in human caring. These activities involve national and international scholars in residence, as well as international connections with colleagues around the world, such as Australia, Brazil, Canada, Korea, Japan, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Scandinavia, Thailand, and Venezuela, among others. Activities such as these continue at the University of Colorado’s International Certificate Program in Caring-Healing, where Watson offers her theory courses for doctoral students.

At University of Colorado School of Nursing, Watson served as chairperson and assistant dean of the undergraduate program. She was involved in planning and implementation of the nursing PhD program and served as coordinator and director of the PhD program between 1978 and 1981. Watson was Dean of University of Colorado School of Nursing and Associate Director of Nursing Practice at University Hospital from 1983 to 1990. During her deanship, she was instrumental in the development of a post-baccalaureate nursing curriculum in human caring, health, and healing that led to a Nursing Doctorate (ND), a professional clinical doctoral degree that in 2005 became the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) degree.

During her career, Watson has been active in many community programs, such as founder and member of the Board of Boulder County Hospice, and numerous other collaborations with area health care facilities. Watson has received several research and advanced education federal grants and awards and numerous university and private grants and extramural funding for her faculty and administrative projects and scholarships in human caring.

The University of Colorado School of Nursing honored Watson as a distinguished professor of nursing in 1992. She received six honorary doctoral degrees from universities in the United States and three Honorary Doctorates in international universities, including Göteborg University in Sweden, Luton University in London, and the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada. In 1993, she received the National League for Nursing (NLN) Martha E. Rogers Award, which recognizes nurse scholars’ significant contributions to advancing nursing knowledge and knowledge in other health sciences. Between 1993 and 1996, Watson served as a member of the Executive Committee and the Governing Board, and as an officer for the NLN, and she was elected president from 1995 to 1996. In 1997, the NLN awarded her an honorary lifetime certificate as a holistic nurse. Finally, in 1999, Watson assumed the nation’s first Murchison-Scoville Endowed Chair of Caring Science and currently is a distinguished professor of nursing.

In 1998, Watson was recognized as a Distinguished Nurse Scholar by New York University, and in 1999, she received the Fetzer Institute’s national Norman Cousins Award in recognition of her commitment to developing, maintaining, and exemplifying relationship-centered care practices (Watson, personal communication, August 14, 2000).

Watson is a Distinguished and/or Endowed Lecturer at national universities, including Boston College, Catholic University, Adelphi University, Columbia University-Teachers College, State University of New York, and at universities and scholarly meetings in numerous foreign countries. Her international activities also include an International Kellogg Fellowship in Australia (1982), a Fulbright Research and Lecture Award to Sweden and other parts of Scandinavia (1991), and a lecture tour in the United Kingdom (1993). Watson has been involved in international projects and has received invitations to New Zealand, India, Thailand, Taiwan, Israel, Japan, Venezuela, Korea, and other places. She is featured in at least 20 nationally distributed audiotapes, videotapes, and/or CDs on nursing theory, a few of which are listed in Points for Further Study at the end of the chapter.

Jean Watson has authored 11 books, shared in authorship of six books, and has written countless articles in nursing journals. The following publications reflect the evolution of her theory of caring from her ideas about the philosophy and science of caring.

Her first book, Nursing: The Philosophy and Science of Caring (1979), was developed from her notes for an undergraduate course taught at the University of Colorado. Yalom’s 11 curative factors stimulated Watson’s thinking about 10 carative factors, described as the organizing framework for her book (Watson, 1979), “central to nursing” (p. 9), and a moral ideal. Watson’s early work embraced the 10 carative factors but evolved to include “caritas,” making explicit connections between caring and love (Watson, personal correspondence, 2004). Her first book was reprinted in 1985 and translated into Korean and French.

Her second book, Nursing: Human Science and Human Care—A Theory of Nursing, published in 1985 and reprinted in 1988 and 1999, addressed her conceptual and philosophical problems in nursing. Her second book has been translated into Chinese, German, Japanese, Korean, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, and probably other languages by now.

Her third book, Postmodern Nursing and Beyond (1999), was presented as a model to bring nursing practice into the twenty-first century. Watson describes two personal life-altering events that contributed to her writing. In 1997, she experienced an accidental injury that resulted in the loss of her left eye and soon after, in 1998, her husband died. Watson states that she is “attempting to integrate these wounds into my life and work. One of the gifts through the suffering was the privilege of experiencing and receiving my own theory through the care from my husband and loving nurse friends and colleagues” (Watson, personal communication, August 31, 2000). This third book has been translated into Portuguese and Japanese. Instruments for Assessing and Measuring Caring in Nursing and Health Sciences (2002), a collection of 21 instruments to assess and measure caring, received the American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year Award.

Her fifth book, Caring Science as Sacred Science (2005), describes her personal journey to enhance understanding about caring science, spiritual practice, the concept and practice of care, and caring-healing work. In this book, she leads the reader through thought-provoking experiences and the sacredness of nursing by emphasizing deep inner reflection and personal growth, communication skills, use of self-transpersonal growth, and attention to both caring science and healing through forgiveness, gratitude, and surrender. It received the American Journal of Nursing 2005 Book of the Year Award.

Recent books include Measuring Caring: International Research on Caritas as Healing (Nelson & Watson, 2011), Creating a Caring Science Curriculum (Hills & Watson, 2011), and Human Caring Science: A Theory of Nursing (Watson, 2012).

Theoretical sources

Watson’s work has been called a philosophy, blueprint, ethic, paradigm, worldview, treatise, conceptual model, framework, and theory (Watson, 1996). This chapter uses the terms theory and framework interchangeably. To develop her theory, Watson (1988) defines theory as “an imaginative grouping of knowledge, ideas, and experience that are represented symbolically and seek to illuminate a given phenomenon” (p. 1). She draws on the Latin meaning of theory “to see” and concludes, “It (Human Science) is a theory because it helps me ‘to see’ more broadly (clearly)” (p. 1). Watson acknowledges a phenomenological, existential, and spiritual orientation from the sciences and humanities as well as philosophical and intellectual guidance from feminist theory, metaphysics, phenomenology, quantum physics, wisdom traditions, perennial philosophy, and Buddhism (Watson, 1995, 1997, 1999, 2005, 2012). She cites background for her theory nursing philosophies and theorists, including Nightingale, Henderson, Leininger, Peplau, Rogers, and Newman, and also the work of Gadow, a nursing philosopher and health care ethicist (Watson, 1985, 1997, 2005, 2012). She connects Nightingale’s sense of deep commitment and calling to an ethic of human service.

Watson attributes her emphasis on the interpersonal and transpersonal qualities of congruence, empathy, and warmth to the views of Carl Rogers and more recent writers of transpersonal psychology. Watson points out that Carl Rogers’ phenomenological approach, with his view that nurses are not here to manipulate and control others but rather to understand, was profoundly influential at a time when “clinicalization” (therapeutic control and manipulation of the patient) was considered the norm (Watson, personal communication, August 31, 2000). In her book, Caring Science as Sacred Science, Watson (2005) describes the wisdom of French philosopher Emmanuael Levinas (1969) and Danish philosopher Knud Løgstrup (1995) as foundational to her work.

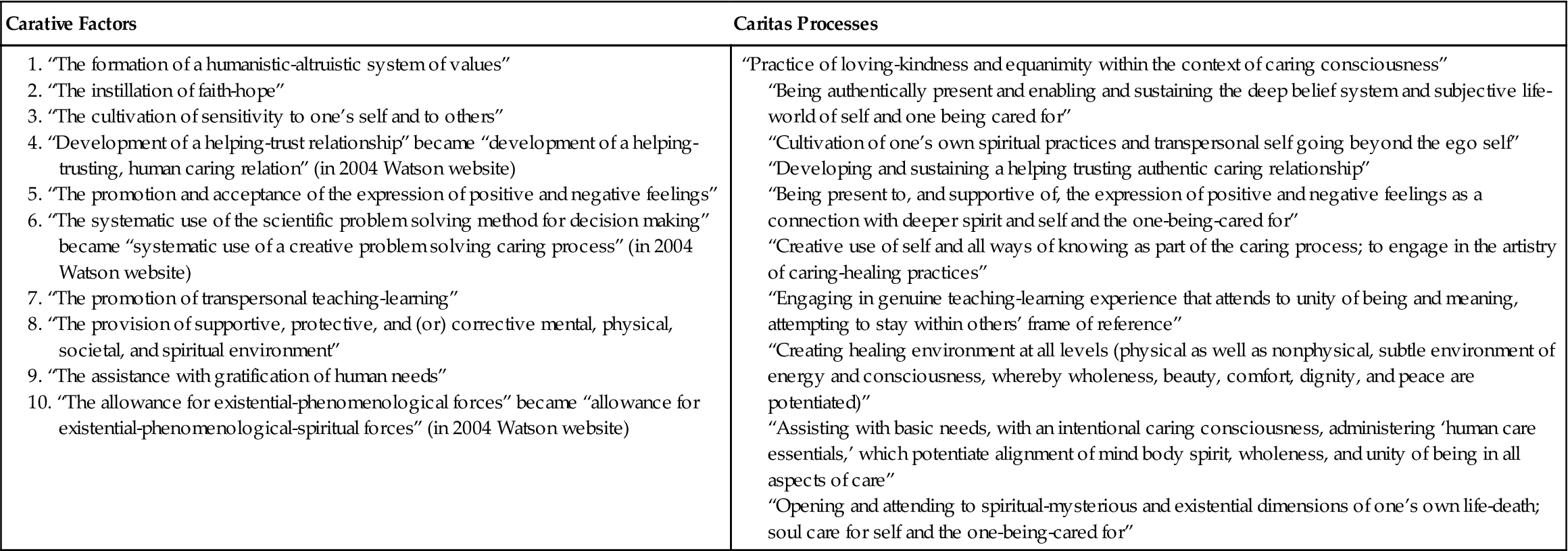

Watson’s main concepts include the 10 carative factors (see Major Concepts & Definitions box and Table 7-1) and transpersonal healing and transpersonal caring relationship, caring moment, caring occasion, caring healing modalities, caring consciousness, caring consciousness energy, and phenomenal file/unitary consciousness. Watson expanded the carative factors to a closely related concept, caritas, a Latin word that means “to cherish, to appreciate, to give special attention, if not loving attention.” As carative factors evolved within an expanding perspective, and as her ideas and values evolved, Watson offered a translation of the original carative factors into clinical caritas processes that suggested open ways in which they could be considered (Table 7-1).

TABLE 7-1

Carative Factors and Caritas Processes

| Carative Factors | Caritas Processes |

1. “The formation of a humanistic-altruistic system of values” 2. “The instillation of faith-hope” 3. “The cultivation of sensitivity to one’s self and to others” 5. “The promotion and acceptance of the expression of positive and negative feelings” 7. “The promotion of transpersonal teaching-learning” 9. “The assistance with gratification of human needs” | “Practice of loving-kindness and equanimity within the context of caring consciousness” “Being authentically present and enabling and sustaining the deep belief system and subjective life-world of self and one being cared for” “Cultivation of one’s own spiritual practices and transpersonal self going beyond the ego self” “Developing and sustaining a helping trusting authentic caring relationship” “Being present to, and supportive of, the expression of positive and negative feelings as a connection with deeper spirit and self and the one-being-cared for” “Creative use of self and all ways of knowing as part of the caring process; to engage in the artistry of caring-healing practices” “Engaging in genuine teaching-learning experience that attends to unity of being and meaning, attempting to stay within others’ frame of reference” “Creating healing environment at all levels (physical as well as nonphysical, subtle environment of energy and consciousness, whereby wholeness, beauty, comfort, dignity, and peace are potentiated)” “Assisting with basic needs, with an intentional caring consciousness, administering ‘human care essentials,’ which potentiate alignment of mind body spirit, wholeness, and unity of being in all aspects of care” “Opening and attending to spiritual-mysterious and existential dimensions of one’s own life-death; soul care for self and the one-being-cared for” |

Modified from Watson, J. (1979). Nursing: The philosophy and science of caring (pp. 9–10). Boston: Little, Brown. (for original carative factors); and Watson, J. (2004). Theory of human caring (website). Denver, (CO): Jean Watson/University of Colorado School of Nursing. Retrieved from: http://hschealth.uchsc.edu/son/faculty/jw_evolution.htm (for caritas processes and revised carative factors).

Watson (1999) describes a “Transpersonal Caring Relationship” as foundational to her theory; it is a “special kind of human care relationship—a union with another person—high regard for the whole person and their being-in-the-world” (p. 63).

Use of empirical evidence

Watson’s research into caring incorporates empiricism but emphasizes approaches that begin with nursing phenomena rather than with the natural sciences (Leininger, 1979). For example, she has used human science, empirical phenomenology, and transcendent phenomenology in her work. She has investigated metaphor and poetry to communicate, convey, and elucidate human caring and healing (Watson, 1987, 2005). In her inquiry and writing, she increasingly incorporated her conviction that a sacred relationship exists between humankind and the universe (Watson, 1997, 2005).

Major assumptions

Watson calls for joining of science with humanities so that nurses have a strong liberal arts background and understand other cultures as a requisite for using Caring Science and a mind-body-spiritual framework. She believes that study of the humanities expands the mind and enhances thinking skills and personal growth. Watson has compared the status of nursing with the mythological Danaides, who attempted to fill a broken jar with water, only to see water flow through the cracks. She believed the study of sciences and humanities was required to seal similar cracks in the scientific basis of nursing knowledge (Watson, 1981, 1997).

Watson describes assumptions for a Transpersonal Caring Relationship extending to multidisciplinary practitioners:

Theoretical assertions

Nursing

According to Watson (1988), the word nurse is both noun and verb. To her, nursing consists of “knowledge, thought, values, philosophy, commitment, and action, with some degree of passion” (p. 53). Nurses are interested in understanding health, illness, and the human experience; promoting and restoring health; and preventing illness. Watson’s theory calls upon nurses to go beyond procedures, tasks, and techniques used in practice settings, coined as the trim of nursing, in contrast to the core of nursing, meaning those aspects of the nurse-patient relationship resulting in a therapeutic outcome that are included in the transpersonal caring process (Watson, 2005; 2012). Using the original and evolving 10 carative factors, the nurse provides care to various patients. Each carative factor and the clinical caritas processes describe the caring process of how a patient attains or maintains health or dies a peaceful death. Conversely, Watson has described curing as a medical term that refers to the elimination of disease (Watson, 1979). As Watson’s work evolved, she increased her focus on the human care process and the transpersonal aspects of caring-healing in a Transpersonal Caring Relationship (1999, 2005).

Watson’s evolving work continues to make explicit that humans cannot be treated as objects and that humans cannot be separated from self, other, nature, and the larger universe. The caring-healing paradigm is located within a cosmology that is both metaphysical and transcendent with the co-evolving human in the universe. She asks others to be open to possibility and to put away assumptions of self and others, to learn again, and to “see” using all of one’s senses.

Personhood (human being)

Watson uses interchangeably the terms human being, person, life, personhood, and self. She views the person as “a unity of mind/body/spirit/nature” (1996, p. 147), and she says that “personhood is tied to notions that one’s soul possess a body that is not confined by objective time and space ….” (Watson, 1988, p. 45). Watson states, “I make the point to use mind, body, soul or unity within an evolving emergent world view-connectedness of all, sometimes referred to as Unitary Transformative Paradigm-Holographic thinking. It is often considered dualistic because I use the three words ‘mind, body, soul.’ I do it intentionally to connote and make explicit spirit/metaphysical—which is silent in other models” (Watson, personal communication, April 12, 1994).

Health

Originally, Watson’s (1979) definition of health was derived from the World Health Organization as, “The positive state of physical, mental, and social well-being with the inclusion of three elements: (1) a high level of overall physical, mental, and social functioning; (2) a general adaptive-maintenance level of daily functioning; (3) the absence of illness (or the presence of efforts that lead to its absence)” (p. 220). Later, she defined health as “unity and harmony within the mind, body, and soul” associated with the “degree of congruence between the self as perceived and the self as experienced” (Watson, 1988, p. 48). Watson (1988) stated further, “illness is not necessarily disease; [instead it is a] subjective turmoil or disharmony within a person’s inner self or soul at some level of disharmony within the spheres of the person, for example, in the mind, body, and soul, either consciously or unconsciously” (p. 47). “While illness can lead to disease, illness and health are [a] phenomenon that is not necessarily viewed on a continuum. Disease processes can also result from genetic, constitutional vulnerabilities and manifest themselves when disharmony is present. Disease in turn creates more disharmony” (Watson, 1985, 1988, p. 48).

Environment

In the original ten carative factors, Watson speaks to the nurse’s role in the environment as “attending to supportive, protective, and or corrective mental, physical, societal, and spiritual environments” (Watson, 1979, p. 10). In later work, she has a much broader view of environment: “the caring science is not only for sustaining humanity, but also for sustaining the planet …. Belonging is to an infinite universal spirit world of nature and all living things; it is the primordial link of humanity and life itself, across time and space, boundaries and nationalities” (Watson, 2003, p. 305). She says that “healing spaces can be used to help others transcend illness, pain, and suffering,” emphasizing the environment and person connection: “when the nurse enters the patient’s room, a magnetic field of expectation is created” (Watson, 2003, p. 305).

Logical form

The framework is presented in a logical form. It contains broad ideas that address health-illness phenomena. Watson’s definition of caring as opposed to curing is to delineate nursing from medicine and classify the body of nursing knowledge as a separate science.

Since 1979, the development of the theory has been toward clarifying the person of the nurse and the person of the patient. Another emphasis has been on existential-phenomenological and spiritual factors. Her works (2005) remind us of the “spirit-filled dimensions of caring work and caring knowledge” (p. x).

Watson’s theory has foundational support from theorists in other disciplines, such as Rogers, Erikson, and Maslow. She is adamant that nursing education incorporate holistic knowledge from many disciplines integrating the humanities, arts, and sciences and that the increasingly complex health care systems and patient needs require nurses to have a broad, liberal education (Sakalys & Watson, 1986).

Watson incorporated dimensions of a postmodern paradigm shift throughout her theory of transpersonal caring. Her theoretical underpinnings have been associated with concepts such as steady-state maintenance, adaptation, linear interaction, and problem-based nursing practice. The postmodern approach moves beyond this point; the redefining of such a nursing paradigm leads to a more holistic, humanistic, open system, wherein harmony, interpretation, and self-transcendence emerge reflecting a epistemological shift.

Application by the nursing community

Practice

Watson’s theory has been validated in outpatient, inpatient, and community health clinical settings and with various populations, including recent applications with attention to patient care essentials (Pipe, Connolly, Spahr, et al., 2012), living on a ventilator (Lindahl, 2011), and simulating care (Diener & Hobbs, 2012). Watson and Foster (2003) described an exemplary application of theory to practice; the Attending Nurse Caring Model (ANCM) is a unique pilot project in a Denver children’s hospital that is modeled after the “Attending” Physician Model. However, unlike a medical/cure model, the ANCM is concerned with the nursing care model. “It is constructed as a Nursing-Caring Science, theory-guided, evidence based, collaborative practice model for applying it to the conduct and oversight of pain management on a 37-bed, post surgical unit” (Watson & Foster, 2003, p. 363). Nurses who participate in the project learn about Watson’s caring theory, carative factors, caring consciousness, intentionality, and caring-healing practices. The mission of the ANCM is to have a continuous caring relationship with children in pain and their families. The ANCM is made visible in a caring-healing presence throughout the hospital. (See Watson’s website [http://www.watsoncaringscience.org] for examples of her theory in practice and further information about the many clinical agencies that use Watson’s work, such as Miami Baptist Hospital, Resurrection Health System [Chicago], Denver Veterans Administration Hospital and Children’s Hospital [Denver], Inova Health System [Virginia], Baptist Central Hospital [Kentucky], Elmhurst Hospital [New York], Pascak Valley Hospital [New Jersey], Sarasota Memorial Hospital and Tampa Memorial Hospital [Florida], and Scripps Memorial Hospital [California], among others.)

Administration/leadership

Watson’s theory calls for administrative practices and business models to embrace caring (Watson, 2006c), even in a health care environment of increased acuity levels of hospitalized individuals, short hospital stays, increasing complexity of technology, and rising expectations in the “task” of nursing. These challenges call for solutions that address health care system reform at a deep and ethical level, and that enable nurses to follow their own professional practice model rather than short-term solutions, such as increasing numbers of beds, sign-on bonuses, and/or relocation incentives for nurses. Many hospitals seeking Magnet status, such as Central Baptist Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, are meeting these challenges by using Watson’s Theory of Human Caring for administrative change. Others call for sustaining a professional environment based on the definition of patient care essentials (Pipe, Connolly, Spahr, et al., 2012). This and other examples of caring administrative practices are described at her website and in her recent article, “Caring Theory as an Ethical Guide to Administrative and Clinical Practices” (Watson, 2006c).

Education

Watson’s writings focus on educating graduate nursing students and providing them with ontological, ethical, and epistemological bases for their practice, along with research directions (Hills & Watson, 2011). Watson’s caring framework has been taught in numerous baccalaureate nursing curricula, including Bellarmine College in Louisville, Kentucky; Assumption College in Worcester, Massachusetts; Indiana State University in Terre Haute; Oklahoma City University; and Florida Atlantic University. In addition, the concepts are used in nursing programs in Australia, Japan, Brazil, Finland, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, to name a few.

Research

Qualitative, naturalistic, and phenomenological methods are relevant to the study of caring and to the development of nursing as a human science (Nelson & Watson, 2011; Watson, 2012). Watson suggests that a combination of qualitative-quantitative inquiry may be useful. There is a growing body of national and international research that tests, expands, and evaluates the theory (DiNapoli, Nelson, Turkel, & Watson, 2010; Nelson & Watson, 2011). Smith (2004) published a review of 40 research studies that specifically used Watson’s theory. Persky, Nelson, Watson, and Bent’s (2008) study used a quantitative approach to determine the attributes of a “Caritas nurse” as part of an effort to initiate Relationship-Based Care (RBC) at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Medical Center. More recently, Nelson and Watson (2011) report on studies carried out in seven countries. Nelson and Watson (2011) present eight caring surveys and other research tools for caritas research, such as differences among international perceptions of caring, nurse and patient relationships, and guidelines for hospitals seeking Magnet status.

Further development

Watson’s recent writings update her theory (Watson, 2012), review caring measurement (Nelson & Watson, 2011), and guide the creation of a caring science curriculum (Hills & Watson, 2011).

Critique

Clarity

Watson uses nontechnical, sophisticated, fluid, and evolutionary language to artfully describe her concepts, such as caring-love, carative factors, and caritas. Paradoxically, abstract and simple concepts such as caring-love are difficult to practice, yet practicing and experiencing these concepts leads to greater understanding. At times, lengthy phrases and sentences are best understood if read more than once. Watson’s inclusion of metaphors, personal reflections, artwork, and poetry make her concepts more tangible and more aesthetically appealing. She has continued to refine her theory and has revised the original carative factors as caritas processes. Critics of Watson’s work have concentrated on her use of undefined or changing/shifting definitions and terms and her focus on the psychosocial rather than the pathophysiological aspects of nursing. Watson (1985) has addressed the critiques of her work in the preface of Nursing: The Philosophy and Science of Caring (1979, 1988); in the preface of Nursing: Human Science and Human Care—A Theory of Nursing (1985),and in Caring Science as Sacred Science (Watson, 2005). Table 7-1 outlines the evolution of Watson’s thinking.

Simplicity

Watson draws on a number of disciplines to formulate her theory. The theory is more about being than about doing, and the nurse must internalize it thoroughly if it is to be actualized in practice. To understand the theory as it is presented, the reader does best by being familiar with the broad subject matter. This theory is viewed as complex when the existential-phenomenological nature of her work is considered, particularly for nurses who have a limited liberal arts background. Although some consider her theory complex, many find it easy to understand and to apply in practice.

Generality

Watson’s theory is best understood as a moral and philosophical basis for nursing. The scope of the framework encompasses broad aspects of health-illness phenomena. In addition, the theory addresses aspects of health promotion, preventing illness and experiencing peaceful death, thereby increasing its generality. The carative factors provide guidelines for nurse-patient interactions, an important aspect of patient care.

The theory does not furnish explicit direction about what to do to achieve authentic caring-healing relationships. Nurses who want concrete guidelines may not feel secure when trying to use this theory alone. Some have suggested that it takes too much time to incorporate the caritas into practice, and some note that Watson’s personal growth emphasis is a quality “that while appealing to some may not appeal to others” (Drummond, 2005, p. 218).

Empirical precision

Watson describes her theory as descriptive; she acknowledges the evolving nature of the theory and welcomes input from others (Watson, 2012). Although the theory does not lend itself easily to research conducted through traditional scientific methods, recent qualitative nursing approaches are appropriate. Recent work on measurement reviews a broad array of international studies and provides research guidelines, design recommendations, and instruments for caring research (Nelson & Watson, 2011).

Derivable consequences

Watson’s theory continues to provide a useful and important metaphysical orientation for the delivery of nursing care (Watson, 2007). Watson’s theoretical concepts, such as use of self, patient-identified needs, the caring process, and the spiritual sense of being human, may help nurses and their patients to find meaning and harmony during a period of increasing complexity. Watson’s rich and varied knowledge of philosophy, the arts, the human sciences, and traditional science and traditions, joined with her prolific ability to communicate, has enabled professionals in many disciplines to share and recognize her work.

Summary

Jean Watson began developing her theory while she was assistant dean of the undergraduate program at the University of Colorado, and it evolved into planning and implementation of its nursing PhD program. Her first book started as class notes that emerged from teaching in an innovative, integrated curriculum. She became coordinator and director of the PhD program when it began 1978 and served until 1981. While serving as Dean of the University of Colorado, School of Nursing, a post-baccalaureate nursing curriculum in human caring was developed that led to a professional clinical doctoral degree (ND). This curriculum was implemented in 1990 and was later merged into the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) degree. Watson initiated the Center for Human Caring, the nation’s first interdisciplinary center with a commitment to develop and use knowledge of human caring for practice and scholarship. She worked from Yalom’s 11 curative factors to formulate her 10 carative factors. She modified the 10 factors slightly over time and developed the caritas processes, which have a spiritual dimension and use a more fluid and evolutionary language.