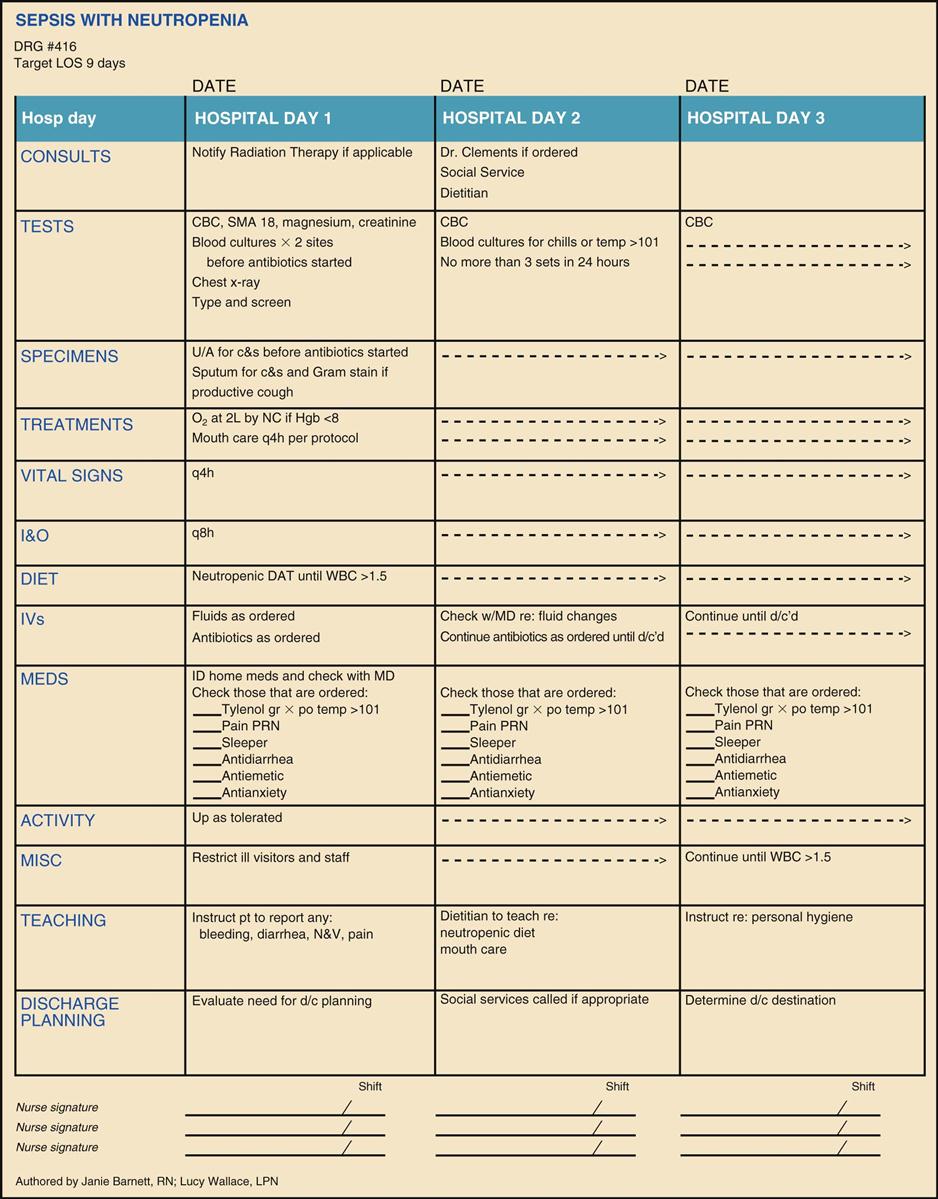

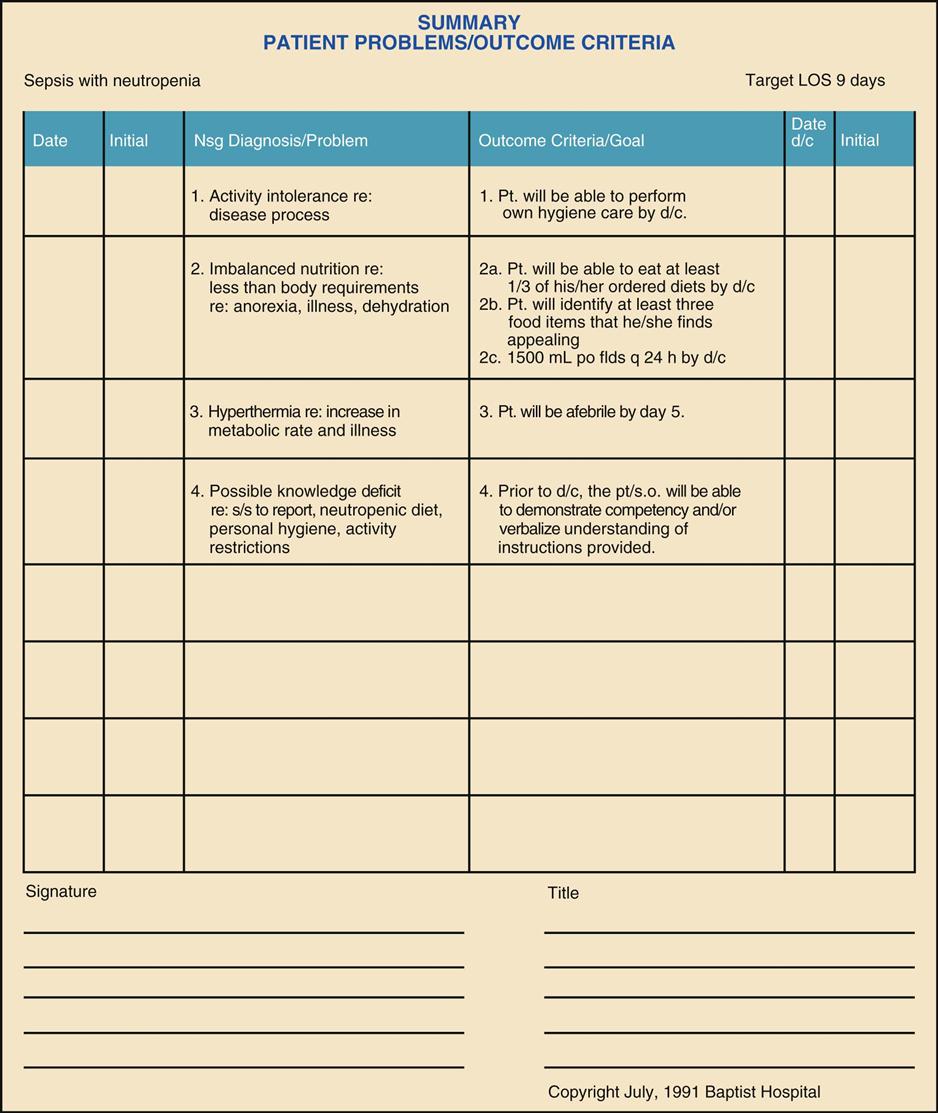

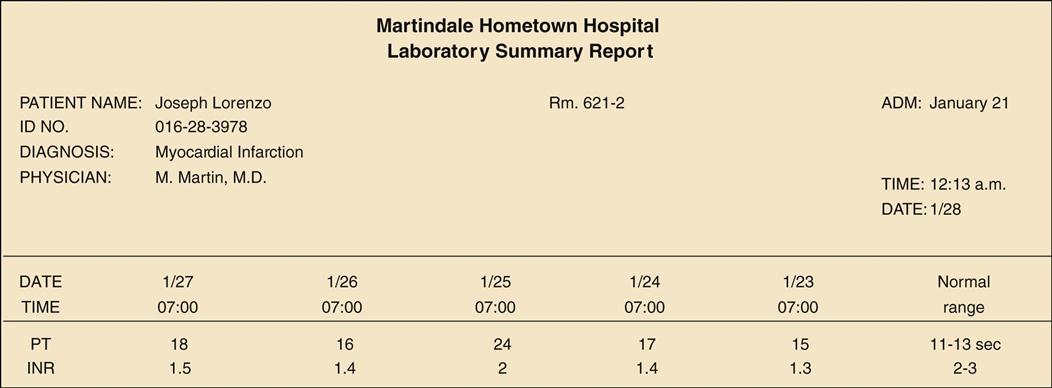

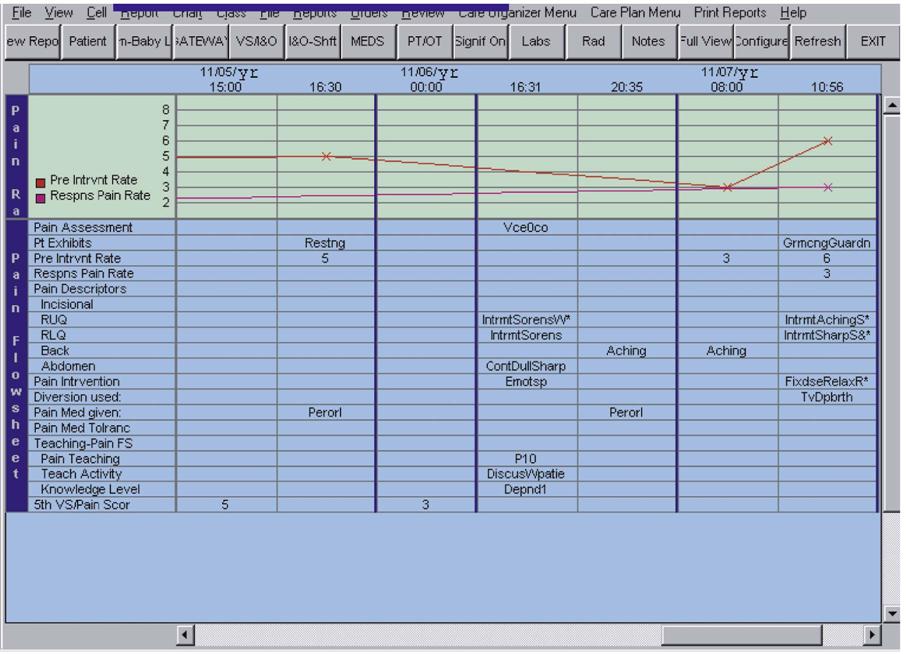

Before medications are administered, the nurse must understand the professional responsibilities associated with medication administration, drug orders, medication delivery systems, and the nursing process as it relates to drug therapy. Ignorance of the nurse’s overall responsibilities as part of the system may result in delays in the receiving and administering of medications and serious administration errors. In either case, care is compromised, and the patient may suffer unnecessarily. The practice of nursing under a professional license is a privilege, not a right. When accepting this privilege, the nurse must understand that this responsibility includes accountability for one’s actions and judgments during the execution of professional duties. An understanding of the nurse practice act and the rules and regulations established by the state boards of nursing for the various levels of entry (i.e., practical nurse, registered nurse, and nurse practitioner) is a solid foundation for beginning practice. Many state boards have developed specific guidelines for nurses to use when practicing nursing. Standards of care are guidelines that have been developed for the practice of nursing. These guidelines are defined by the nurse practice act of each state, by state and federal laws that regulate health care facilities, by The Joint Commission, and by professional organizations such as the American Nurses Association and other specialty nursing organizations (e.g., the Intravenous Nurses Society). Nurses must also be familiar with the established policies of the employing health care agency. Policies developed by the health care agency must adhere to the minimum standards of state regulatory authorities; however, agency policies may be more stringent than those that are recognized by the state. Employment by the agency implies the willingness of the nurse to adhere to established standards and to work within established guidelines. Examples of policy statements that are related to medication administration include the following: Before administering any medication, the nurse must have a current license to practice, a clear policy statement that authorizes the act, and a medication order signed by a practitioner who is licensed with prescriptive privileges at that institution. The nurse must understand the individual patient’s diagnosis and symptoms that correlate with the rationale for drug use. The nurse should also know why a medication is ordered as well as its expected actions, usual dosing, proper dilution, route and rate of administration, adverse effects and the contraindications for the use of a particular drug. If drugs are to be administered with the use of the same syringe or at the same intravenous (IV) site, drug compatibility should be confirmed before administration. If the nurse is unsure about any of these key medication points, then he or she must consult an authoritative resource or the hospital pharmacist before administering a medication. The nurse must be accurate when calculating, preparing, and administering medications. The nurse must assess the patient to be certain that therapeutic and adverse effects associated with the medication regimen are reported. Nurses must be able to collect patient data at regularly scheduled intervals and to record observations in the patient’s chart when evaluating a treatment’s effectiveness. Claiming unfamiliarity with any of these nursing responsibilities when an avoidable complication arises is unacceptable; in fact, it is considered negligence of nursing responsibility. Nurses must take an active role in educating the patient, the family, and significant others in preparation for the patient’s discharge from the health care environment. A person’s health will improve only to the extent that the patient understands how to care for himself or herself. Specific teaching goals should be developed and implemented. Nursing observations and the patient’s progress toward the mastery of skills should be charted to document the patient’s degree of understanding. The patient’s chart or the electronic medical record is a primary source of information that is necessary for the patient assessment so that the nurse can create and implement plans for patient care. It is also where the nurse provides the documentation of the nursing assessments performed, the observations reported to the physician for further verification, the basic nursing measures implemented (e.g., daily treatments), the patient teaching performed, and the observed responses to therapy. This record serves as the communication link among all members of the health care team regarding the patient’s status, the care provided, and the patient’s progress. The chart is a legal document that describes the patient’s health, that lists diagnostic and therapeutic procedures initiated, and that describes the patient’s response to these measures. The chart must be kept current as long as the patient is in the hospital. After the patient’s discharge, this record is maintained according to policies within the institution. The patient record may be used for research to compare responses to selected therapies in a sampling of patients with similar diagnoses. Although each health care facility uses a slightly different format, the basic patient chart consists of the following elements. The summary sheet gives the patient’s name, address, date of birth, attending physician, gender, marital status, allergies, nearest relative, occupation and employer, insurance carrier and other payment information, religious preference, date and time of admission to the hospital, previous hospital admissions, and admitting problem or diagnosis. The date and time of discharge are added when appropriate. The admission consent form grants permission to the health care facility and the health care provider to provide treatment. Other types of consent forms are used during the course of a hospitalization, such as an operative procedure permit or consent, an invasive procedure consent, a blood-product consent, and a consent to bill the patient’s insurance carrier. All procedures and treatments are ordered by the health care provider on the physician’s order form (Figure 7-1). These orders include general care (e.g., activity, diet, frequency of vital signs), laboratory tests to be completed, other diagnostic procedures (e.g., radiography, electrocardiography, computed tomography), and all medications and treatments (e.g., physical or occupational therapy. During admission to the hospital, the patient is interviewed by a health care provider and given a physical examination. The health care provider records the findings on the history and physical examination form and lists the problems to be corrected (e.g., the diagnoses). The history and physical examination form is often referred to as “the H&P.” The attending health care provider records frequent observations of the patient’s health status in the progress notes. In most hospitals, other health professionals (e.g., pharmacists, dietitians, physical and respiratory therapists) may record observations and suggestions. Critical pathways are also referred to as integrated care plans, care maps or clinical maps (Figure 7-2), and clinical trajectories. This document is a comprehensive standardized plan of care that is individualized on admission by the health care provider and the nurse case manager. Critical pathways describe a multidisciplinary plan that is used by all caregivers to track the patient’s progress toward expected outcomes within a specified period. Standardized outcomes and timetables require health care providers to make assessments regarding the patient’s progress toward the goals of discharge while maintaining quality care. Revisions are made as necessary and communicated to all members so that patient care continues uninterrupted toward the discharge goals. Critical pathway programs are developed to monitor the care delivered at a specific clinical setting, but they are based on data that are gathered from many clinical sites. The use of standardized outcomes is designed to improve the quality of care provided, to reduce the costs of care, and to document the effect of the nursing care on patient outcomes. Evidence-based medicine or practice is the application of data from scientific research to make clinical decisions about the care of individual patients. Past medical practice relied largely on the clinical intuition of practitioners. The shift to evidence-based decision making is possible because of the vast array of clinical studies that have been completed and the existence of large databases, which can be quickly accessed and searched for the best scientific evidence when making medical decisions. An example of this concept that is seen in today’s health care institutions is the quality measures known as core measures. Core measures are measures of care that are tracked to show how often hospitals and health care providers use the care recommendations identified by evidence-based practice standards for patients who are being treated for conditions such as heart attack, heart failure, and pneumonia or for patients who are undergoing surgery. Hospitals voluntarily submit data from the medical records of adults who have been treated for these conditions. Although the format varies among institutions, the nurses’ notes generally start with the nursing history. On admission, the nurse performs a complete health assessment of the patient. This process includes a head-to-toe physical assessment, and it also incorporates a patient and family history that provides insights into individual and family needs, life patterns, psychosocial and cultural data, and spiritual needs. This assessment will serve as the basis for the development of the individualized care plan and as a baseline for comparison when ongoing assessment data are gathered. Nurses record the following in their notes: ongoing assessments of the patient’s condition; responses to nursing interventions ordered by the physician (e.g., treatments or medications) or to those initiated by the nurse (e.g., skin care, patient education); evaluations of the effectiveness of nursing interventions; procedures completed by other health care professionals (e.g., wound cleaning by a physician, fitting for a prosthesis by a prosthetician); and other pertinent information (e.g., physician or family visits, patient’s responses after these visits). Entries may be made on the nurses’ notes or flow sheets, throughout a shift, but general guidelines include the following: (1) completing records, including vital signs, immediately after assessing the patient, whether when he or she is first admitted or after he or she returns from a diagnostic procedure or therapy; (2) recording all “as needed” (PRN) medications immediately after administration and addressing the effectiveness of the medication; (3) recording change in the patient’s status and who was notified (e.g., health care provider, manager, patient’s family); (4) discussing the treatment of a sudden change in the patient’s status; and (5) recording information about the transfer, discharge, or death of a patient. In addition to the accurate charting of the observations in a clear and concise form, the nurse should report significant changes in a patient’s status to the charge nurse. The charge nurse then makes a nursing judgment regarding the notification of the attending health care provider. Nurses’ notes are quickly being replaced by computerized charting methods that allow the nurse to document findings and basic care delivered using multiple screens of data and checklist-type formats. After the initial data collection, the nurse develops an individualized nursing care plan. Care plans incorporate nursing diagnoses, critical pathway information, and physician-ordered and nursing-ordered care (see Nursing Care Plan). Most acute care facilities require the nurse to chart against each identified nursing diagnosis stated in the care plan every 8 hours. Care plans are evaluated and modified on a continuum throughout the course of treatment. The plan should be shared with the health care team to ensure an interdisciplinary approach to care. Many institutions have developed standardized care plans for the various nursing diagnoses. It is the nurse’s responsibility to identify those diagnoses, interventions, and outcomes that are appropriate for the patient. Nursing Care Plan: Adapted from Potter PA, Perry AG: Fundamentals of nursing, ed 6, St. Louis, 2005, Mosby. *Outcome classification labels and interventions from Moorhead S, Johnson M, Maas M, Swanson E: Nursing outcomes classification (NOC), ed 4, St Louis, 2008, Mosby. All laboratory test results are kept in one section of the chart (i.e., the laboratory tests record). Hospitals that use computerized reports may list consecutive values of the same test if that test has been repeated several times (e.g., electrolytes). Computerized laboratory data access provides online laboratory results as soon as the tests are completed. Other hospitals may attach small report forms to a full-sized backing sheet as each report returns from the laboratory. Because some medication doses are based on daily blood studies, it is important to be able to locate these data within the patient’s chart. Figure 7-3 illustrates a series of international normalized ratio (INR) and prothrombin time (PT) results for a patient who is receiving warfarin. The graphic record (Figure 7-4, A) is an example of the manual recording of temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure. Figure 7-4, B, is a computer-database–generated example of the vital signs, fluid intake and output, glucose, dietary intake, and other information to be used for the ongoing assessment of the patient’s status. Pain assessment, which is now considered the fifth vital sign, can also be recorded in a graphic form. In addition to the graphic recording of pain, assessments of pain can be found under other flow sheets in the chart that will record the details of the pain events. The medication administration record (MAR) details the pain medications that the patient received. Figure 7-5 illustrates preintervention and postintervention ratings as well as pain descriptors, pain interventions, medications administered, and patient teaching completed. Flow sheets are a condensed form for recording information for the quick comparison of data. Examples of flow sheets in common use are diabetic, pain (see Figure 7-5), and neurologic flow sheets. The graphic record that is used for recording vital signs is another type of a flow sheet. When other physicians or health professionals are asked to consult about a patient, the specialist’s summary of findings, diagnoses, and recommendations for treatment are recorded in the consultation reports section. Reports of surgery, electroencephalography, electrocardiography, pulmonary function tests, radioactive scans, and radiography are usually recorded in the other diagnostic reports section of the patient’s chart. The medication profile lists all medications to be administered and is printed from the computerized patient database, thereby ensuring that the pharmacist and the nurse have identical medication profiles for the patient. The medications are usually grouped according to the following categories: those scheduled to be given on a regular basis (e.g., every 6 hours, twice daily), parenteral, stat (from the Latin statim, meaning “immediately”), and preoperative orders. PRN medications are those medications that are given on an “as needed” basis and are usually listed at the bottom of the profile, or they may be found on a separate page as unscheduled medication orders. The medication administration record (MAR) is a record of the time that the medication was administered and identifies who gave it (Figure 7-6, A). Generally, the nurse records and initials the time that the medication was given and also places his or her initials, name, and title in a designated place provided in the record for documentation. Medication profiles are kept in a notebook or clipboard file on the medication cart for the 24-hour period that they are in use; they then become a permanent part of the patient’s chart. In the acute care setting, a new profile is generated every 24 hours at the same time that the unit-dose cart is refilled. Figure 7-6, B. on p. 90, is an example of an electronic-database–generated medication sheet that lists all scheduled medications for an 8-hour shift. By clicking the cursor on the highlighted area (i.e., regular insulin, in this illustration), a window opens to reveal details of the order. In the long-term care setting, the MAR uses the same principles; however, it generally provides a space for medications to be recorded Some clinical settings use a separate PRN (from the Latin pro re nata, meaning “as circumstances require”) medication record rather than the MAR to record the date, the time, the PRN medication administered, the dose, the reason for administering the PRN medication, and the patient’s response to the drug given. In most clinical settings, which involve the use of electronic forms of charting, the PRN medications are recorded on the same MAR. The patient education record provides a means of documenting the health teaching provided to the patient, the family, or significant others, and it includes statements about the patient’s mastery of the content presented. Additional forms included in a patient’s chart depend on the therapy prescribed. These may include the following: separate medication administration records; health teaching records; operative and anesthesiology records; recovery room records; physical, occupational, or speech therapy records; inhalation therapy reports; and a diabetic’s daily record of insulin dosage and blood glucose (sugar) test results. Each page that is placed in the patient’s chart is imprinted with the patient’s name, registration number, and unit or room number. Nurses often use data from all of these sections to formulate a plan of nursing care. The Kardex (Figure 7-7) is a large index-type card that is usually kept in a flip file or a separate holder that contains pertinent information such as the patient’s name, diagnosis, allergies, treatments, and the nursing care plan. When the unit-dose system is used, medications are not listed on the Kardex rather they are listed separately on the medication profile. Although the Kardex is used primarily by nurses, patient data can be quickly accessed by all members of the health care team. The Kardex is often completed in pencil and updated regularly. Because it is not a legal document, it is destroyed when the patient is discharged from the institution. Traditional Kardex information is evolving into an electronic database format that is continually updated throughout each shift. The latest information is printed at the start of each shift. Regardless of the method of charting used, the documentation process needs to adhere to The Joint Commission standards that incorporate established standards of care. The Joint Commission requires that all charting methodologies incorporate nursing process criteria as well as evidence of teaching and discharge planning. When more than one health discipline is providing patient care, a multidisciplinary care plan must be completed. This facilitates communication among interdisciplinary team members and health care providers. Improving patient safety at the point of care has become standard in every health care institution (see pp. 97-100). The format and extent of use of electronic database charting vary widely among institutions, but each method incorporates the standards of care and The Joint Commission requirements. Some clinical sites have extensive online electronic charting developed, whereas others have little or none. For example, one hospital may elect to combine all of the elements formerly found in the Kardex, the care plan, the MAR, and the critical pathways into one printable document known as a patient profile that the nurse can access for each 8-hour shift. The nurse can also print out a summary of the laboratory test results and a summary of the nursing assessment data from past shifts. Regardless of the methodology used, the adage “If you didn’t chart it, it didn’t happen” still holds true.

Principles of Medication Administration and Medication Safety

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

Objectives

Key Terms

Legal and Ethical Considerations

Standards of Care

Patient Charts

Contents of Patient Charts

Summary Sheet

Consent Forms

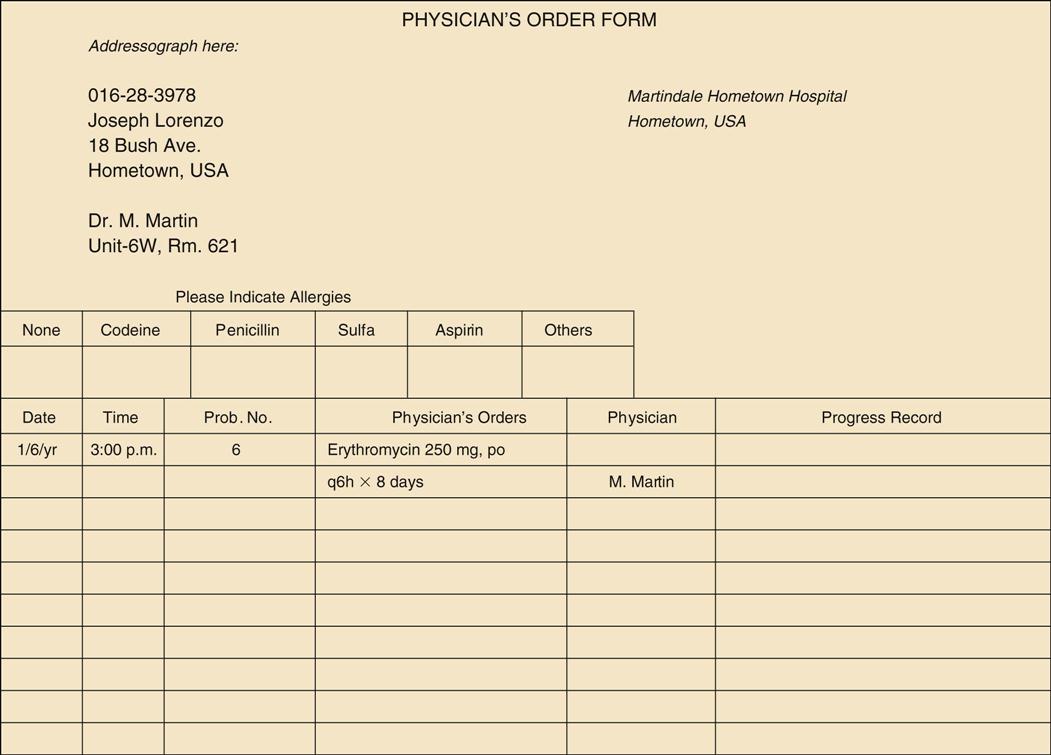

Physician’s Order Form

History and Physical Examination Form

Progress Notes

Critical Pathways

Evidence-Based Medicine

Nurses’ Notes

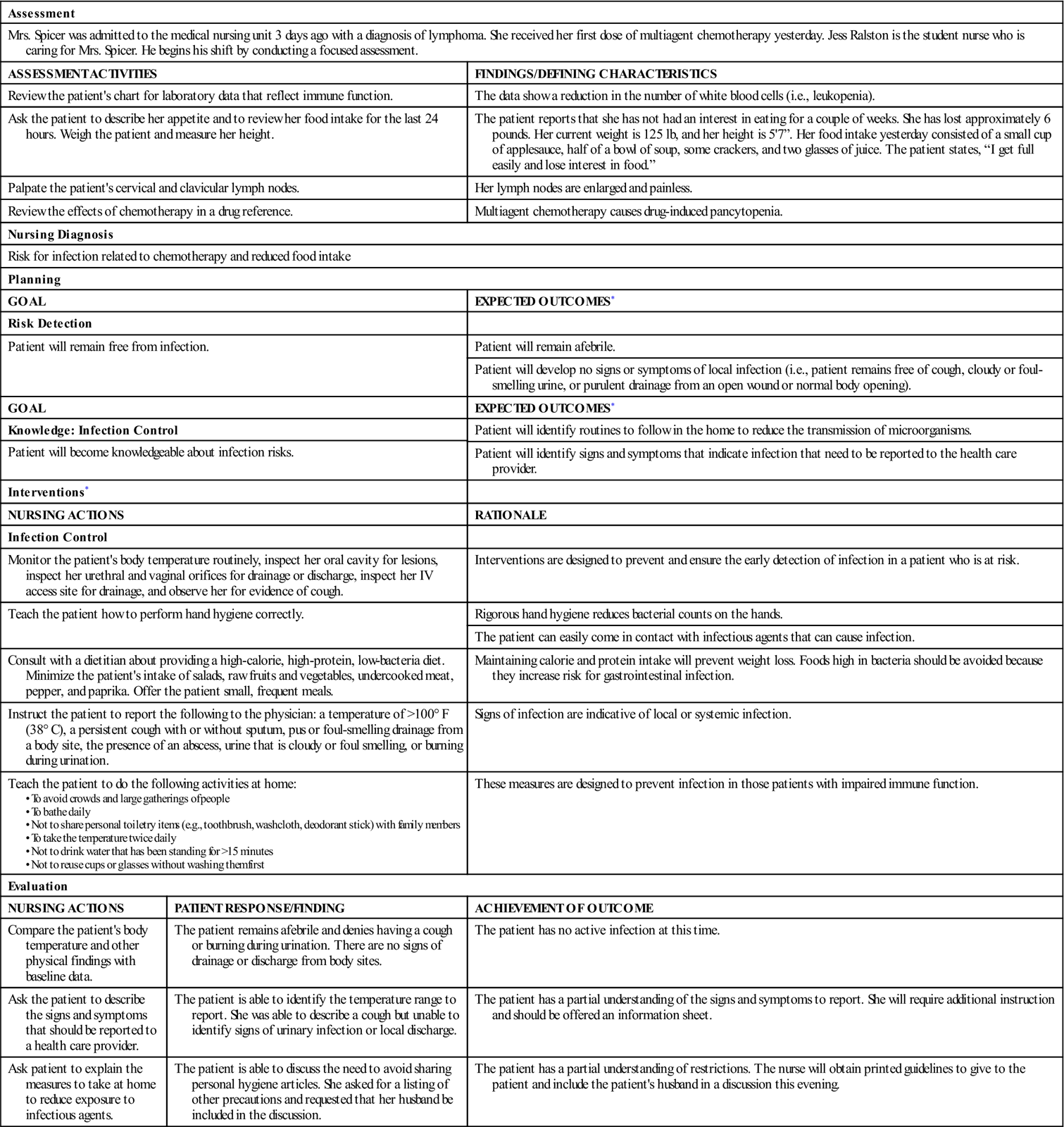

Nursing Care Plans

Risk for Infection

Assessment

Mrs. Spicer was admitted to the medical nursing unit 3 days ago with a diagnosis of lymphoma. She received her first dose of multiagent chemotherapy yesterday. Jess Ralston is the student nurse who is caring for Mrs. Spicer. He begins his shift by conducting a focused assessment.

ASSESSMENT ACTIVITIES

FINDINGS/DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS

Review the patient’s chart for laboratory data that reflect immune function.

The data show a reduction in the number of white blood cells (i.e., leukopenia).

Ask the patient to describe her appetite and to review her food intake for the last 24 hours. Weigh the patient and measure her height.

The patient reports that she has not had an interest in eating for a couple of weeks. She has lost approximately 6 pounds. Her current weight is 125 lb, and her height is 5’7”. Her food intake yesterday consisted of a small cup of applesauce, half of a bowl of soup, some crackers, and two glasses of juice. The patient states, “I get full easily and lose interest in food.”

Palpate the patient’s cervical and clavicular lymph nodes.

Her lymph nodes are enlarged and painless.

Review the effects of chemotherapy in a drug reference.

Multiagent chemotherapy causes drug-induced pancytopenia.

Nursing Diagnosis

Risk for infection related to chemotherapy and reduced food intake

Planning

GOAL

EXPECTED OUTCOMES*

Risk Detection

Patient will remain free from infection.

Patient will remain afebrile.

Patient will develop no signs or symptoms of local infection (i.e., patient remains free of cough, cloudy or foul-smelling urine, or purulent drainage from an open wound or normal body opening).

GOAL

EXPECTED OUTCOMES*

Knowledge: Infection Control

Patient will identify routines to follow in the home to reduce the transmission of microorganisms.

Patient will become knowledgeable about infection risks.

Patient will identify signs and symptoms that indicate infection that need to be reported to the health care provider.

Interventions*

NURSING ACTIONS

RATIONALE

Infection Control

Monitor the patient’s body temperature routinely, inspect her oral cavity for lesions, inspect her urethral and vaginal orifices for drainage or discharge, inspect her IV access site for drainage, and observe her for evidence of cough.

Interventions are designed to prevent and ensure the early detection of infection in a patient who is at risk.

Teach the patient how to perform hand hygiene correctly.

Rigorous hand hygiene reduces bacterial counts on the hands.

The patient can easily come in contact with infectious agents that can cause infection.

Consult with a dietitian about providing a high-calorie, high-protein, low-bacteria diet. Minimize the patient’s intake of salads, raw fruits and vegetables, undercooked meat, pepper, and paprika. Offer the patient small, frequent meals.

Maintaining calorie and protein intake will prevent weight loss. Foods high in bacteria should be avoided because they increase risk for gastrointestinal infection.

Instruct the patient to report the following to the physician: a temperature of >100° F (38° C), a persistent cough with or without sputum, pus or foul-smelling drainage from a body site, the presence of an abscess, urine that is cloudy or foul smelling, or burning during urination.

Signs of infection are indicative of local or systemic infection.

Teach the patient to do the following activities at home:

These measures are designed to prevent infection in those patients with impaired immune function.

Evaluation

NURSING ACTIONS

PATIENT RESPONSE/FINDING

ACHIEVEMENT OF OUTCOME

Compare the patient’s body temperature and other physical findings with baseline data.

The patient remains afebrile and denies having a cough or burning during urination. There are no signs of drainage or discharge from body sites.

The patient has no active infection at this time.

Ask the patient to describe the signs and symptoms that should be reported to a health care provider.

The patient is able to identify the temperature range to report. She was able to describe a cough but unable to identify signs of urinary infection or local discharge.

The patient has a partial understanding of the signs and symptoms to report. She will require additional instruction and should be offered an information sheet.

Ask patient to explain the measures to take at home to reduce exposure to infectious agents.

The patient is able to discuss the need to avoid sharing personal hygiene articles. She asked for a listing of other precautions and requested that her husband be included in the discussion.

The patient has a partial understanding of restrictions. The nurse will obtain printed guidelines to give to the patient and include the patient’s husband in a discussion this evening.

Laboratory Tests Record

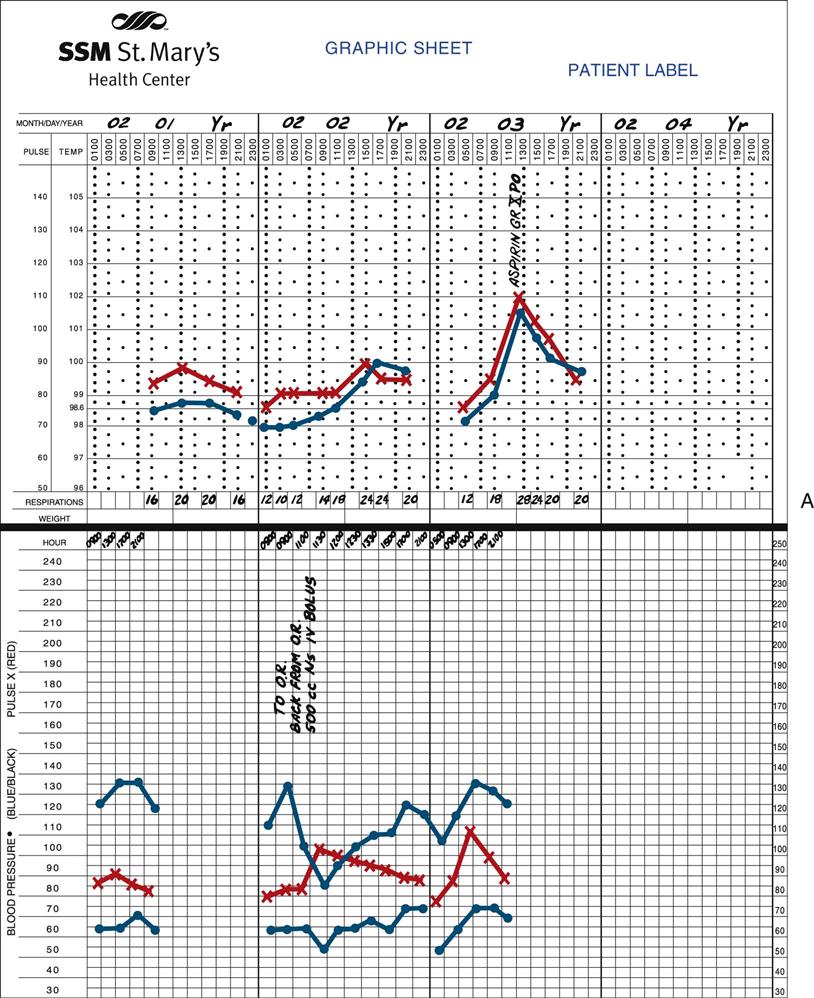

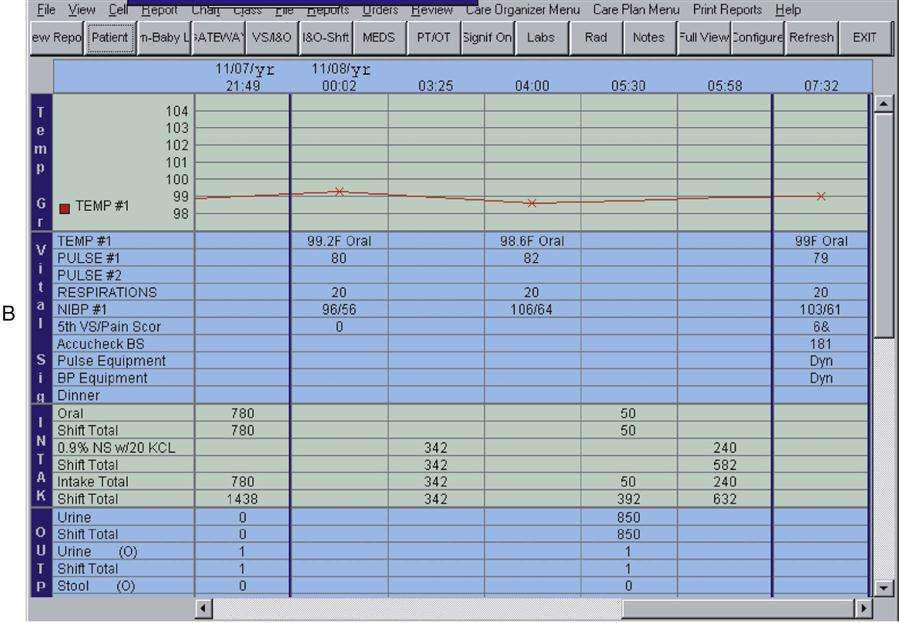

Graphic Record

Flow Sheets

Consultation Reports

Other Diagnostic Reports

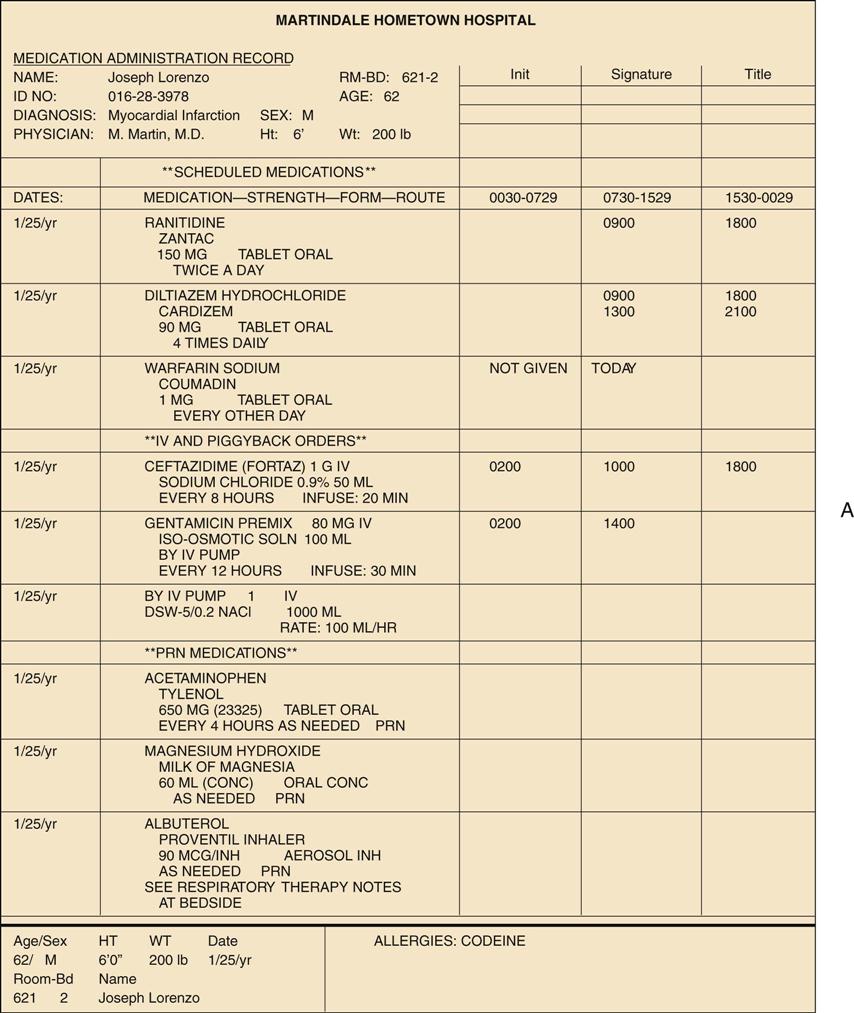

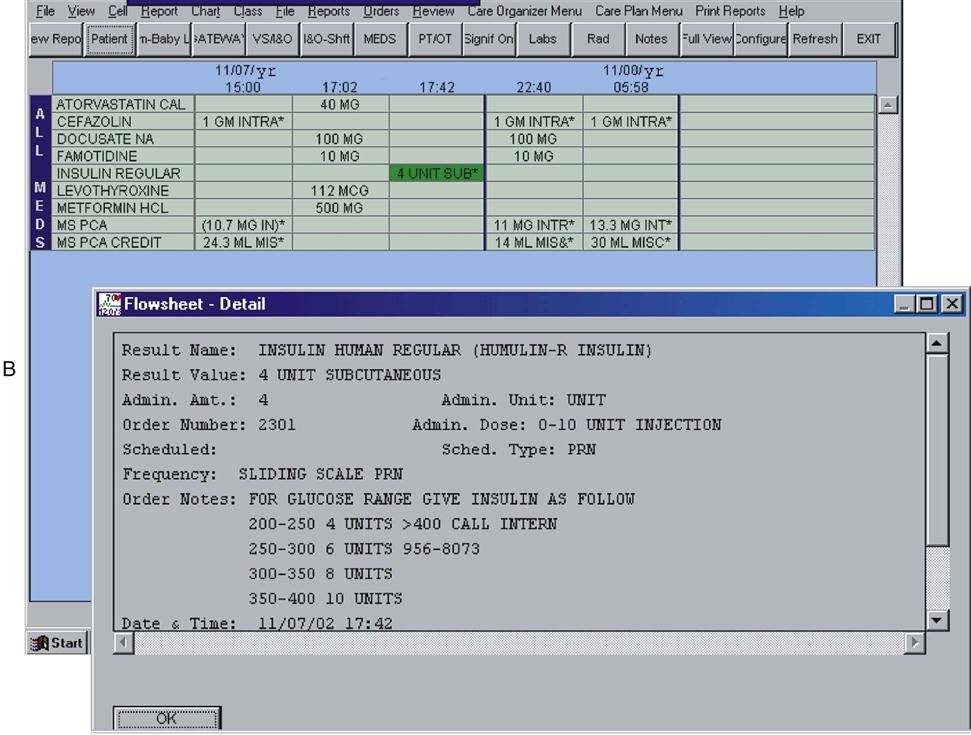

Medication Profile and Medication Administration Record

![]() for up to 1 month. The MAR also includes the name of the pharmacy that dispensed the prescribed medications and the assigned prescription number. Medications that are prescribed for residents in the long-term care setting must be reviewed on a scheduled basis; therefore, the MAR identifies the reviewer and the date of review.

for up to 1 month. The MAR also includes the name of the pharmacy that dispensed the prescribed medications and the assigned prescription number. Medications that are prescribed for residents in the long-term care setting must be reviewed on a scheduled basis; therefore, the MAR identifies the reviewer and the date of review.

PRN or Unscheduled Medication Record

Patient Education Record

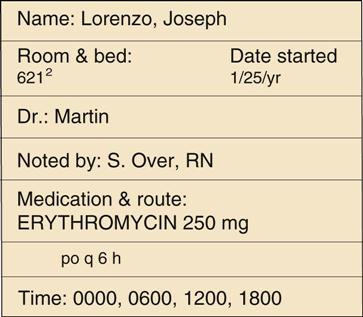

Kardex Records

Evolving Charting Methodologies

Drug Distribution Systems

Objective

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

7. Principles of Medication Administration and Medication Safety

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

) (

) ( ) (

) ( ) (

) ( ) (

) ( ) (

) ( ) (

) ( ) (

) ( ) (

) ( ) (

) ( ) (

) ( ) (

) ( ) (

) ( ) (

) ( ) (

) (