Community Health Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation

Diane C. Martins and Patricia M. Burbank*

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Describe the concept “community as client.”

2. Apply the nursing process to the larger aggregate within a system’s framework.

3. Describe the steps in the health planning model.

5. Recognize major health planning legislation.

7. Describe the community health nurse’s role in health planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Key terms

certificate of need (CON)

community as client

health planning

Health Planning Model

Hill-Burton Act

key informant

National Health Planning and Resources Development Act

Partnership for Health Program (PHP)

Regional Medical Programs (RMPs)

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

Health planning for and with the community is an essential component of community health nursing practice. The term health planning seems simple, but the underlying concept is quite complex. Like many of the other components of community health nursing, health planning tends to vary at the different aggregate levels. Health planning with an individual or a family may focus on direct care needs or self-care responsibilities. At the group level, the primary goal may be health education, and, at the community level, health planning may involve population disease prevention or environmental hazard control. The following example illustrates the interaction of community health nursing roles with health planning at a variety of aggregate levels

.

Implementing such a comprehensive plan is time consuming and requires community involvement and resources. The nurse enlisted the aid of school officials and other community professionals. Time will reveal the plan’s long-term effectiveness in reducing teen pregnancy.

This example shows how nurses can and should become involved in health planning. Teen pregnancy is a significant health problem and often results in lower education and lower socioeconomic status, which can lead to further health problems. The nurse’s assessment and planned interventions involved individual teenagers, parents and families, the school system, and community resources.

This chapter provides an overview of health planning and evaluation from a nursing perspective. It also describes a model for student involvement in health planning projects and a review of significant health planning legislation.

Overview of health planning

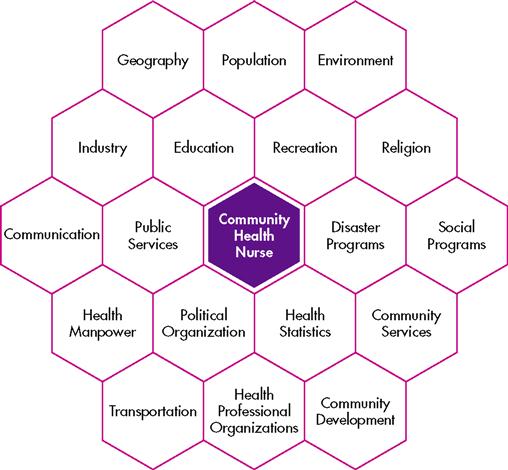

One of the major criticisms of community health nursing practice involves the shift in focus from the community and larger aggregate to family caseload management or agency responsibilities. When focusing on the individual or family, nurses must remember that these clients are members of a larger population group or community, and environmental factors influence them. Nurses can identify these factors and plan health interventions by implementing an assessment of the entire aggregate or community. Figure 7-1 illustrates this process.

The concept of “community as client” is not new. Lillian Wald’s work at New York City’s Henry Street settlement in the late 1800s exemplifies this concept. At the Henry Street settlement, Miss Wald, Mary Brewster, and other public health nurses worked with extremely poor immigrants.

The “case” element in Wald’s early reports received less and less emphasis; she instinctively went beyond the symptoms to appraise the whole individual. She observed that one could not understand the individual without understanding the family and saw that the family was in the grip of larger social and economic forces, which it could not control (Duffus, 1938).

The early beginnings of public health nursing incorporated visits to the homebound ill and applied the nursing process to larger aggregates and communities to improve health for the greatest number of people. Wald’s goals, and those of other public health nurses, were health promotion and disease prevention for the entire community (Silverstein, 1985). Health planning at the aggregate or community level is necessary to accomplish these goals.

Through the 1950s, public health nursing adopted Wald’s nursing concepts, which focused on mobilizing communities to solve local problems, treat the poor, and improve the environmental conditions that fostered disease. During the 1950s, social changes such as suburbanization, increased family mobility, and enhanced government health expenditures updated nursing roles. Since the mid-1960s, there has been a shift from public health nursing, which emphasizes community care, to community health nursing, which includes all nonhospital nursing activities. New trends constantly emerge through health care reform debates. It has become more important to use nurses as primary care providers in the health care system. A continued shift into the community requires that community health nurses become increasingly visible and vocal leaders of health care reform.

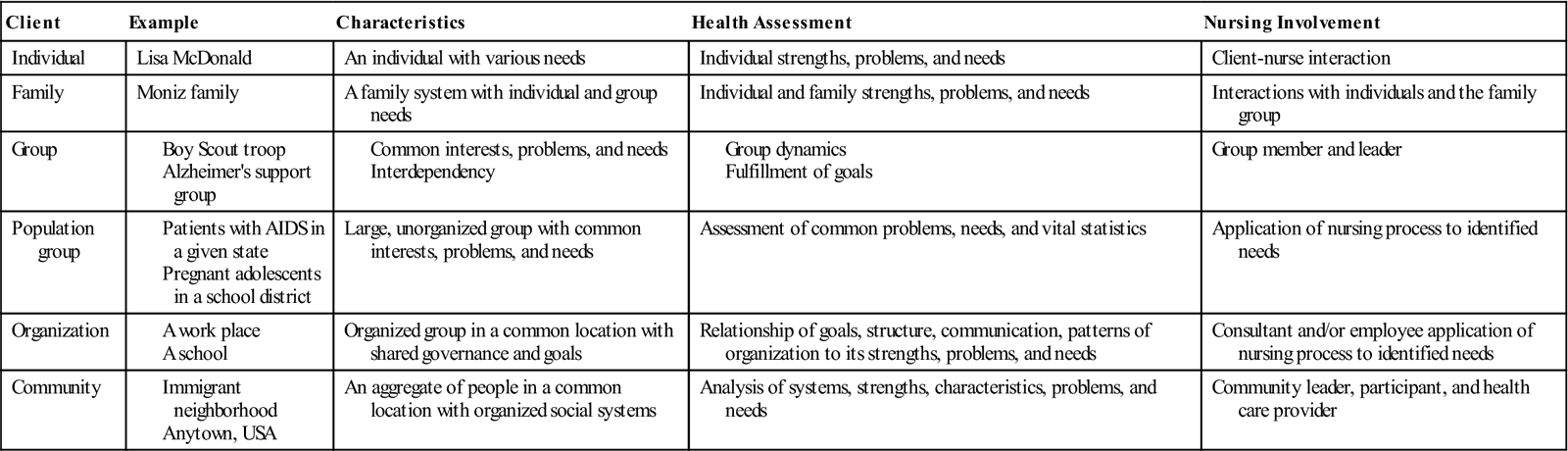

The increased focus on community-based nursing practice yields a greater emphasis on the aggregate becoming the client or care unit. However, the community health nurse should not neglect nursing care at the individual and family levels by focusing on health care only at the aggregate level. Rather, the nurse can use this community information to help understand individual and family health problems and improve their health status. Table 7-1 illustrates the differences in community health nursing practice at the individual, family, and community levels.

TABLE 7-1

Levels of Community Health Nursing Practice

However, before nurses can participate in health care planning, they must be knowledgeable about the process and comfortable with the concept of community as client or care focus. It is essential that undergraduate and graduate nursing programs integrate these concepts into the curricula. If basic and advanced nursing education includes health planning, the student becomes aware of the process and the professional involvement opportunities.

Early efforts to provide students with learning experiences in community health investigation included Hegge’s (1973) use of learning packets for independent study and Ruybal’s opportunities for students to apply epidemiological concepts in community program planning and evaluation (Ruybal, Bauwens, and Fasla, 1975). However, neither of these approaches presented a complete model that incorporated the nursing process into a health planning framework. Several other authors, including Budgen and Cameron (2003) and Shuster and Goeppinger (2008), described the community health planning process. However, none of these models uses practical examples for actual student implementation throughout the entire process.

Health planning model

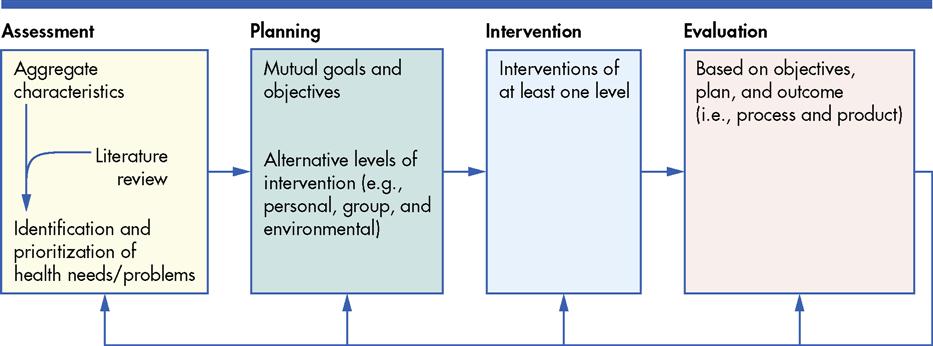

A model based on Hogue’s (1985) group intervention model was developed in response to this need for population focus. The Health Planning Model aims to improve aggregate health and applies the nursing process to the larger aggregate within a systems framework. Figure 7-2 depicts this model. Incorporated into a health planning project, the model can help students view larger client aggregates and gain knowledge and experience in the health planning process. Nurses must carefully consider each step in the process, using this model. Box 7-1 outlines these steps. In addition, Box 7-2 provides the systems framework premises that nurses should incorporate.

Several considerations affect how nurses choose a specific aggregate for study. The community may have extensive or limited opportunities appropriate for nursing involvement. Additionally, each community offers different possibilities for health intervention. For example, an urban area might have a variety of industrial and business settings that need assistance, whereas a suburban community may offer a choice of family-oriented organizations such as boys and girls clubs and parent-teacher associations that would benefit from intervention.

A nurse should also consider personal interests and strengths in selecting an aggregate for intervention. For example, the nurse should consider whether he or she has an interest in teaching health promotion and preventive health or in planning for organizational change, whether his or her communication skills are better suited to large or small groups, and whether he or she has a preference for working with the elderly or with children. Thoughtful consideration of these and other variables will facilitate assessment and planning.

Assessment

To establish a professional relationship with the chosen aggregate, a community health nurse must first gain entry into the group. Good communication skills are essential to make a positive first impression. The nurse should make an appointment with the group leaders to set up the first meeting.

The nurse must initially clarify his or her position, organizational affiliation, knowledge, and skills. The nurse should also clarify mutual expectations and available times. Once entry is established, the nurse continues negotiation to maintain a mutually beneficial relationship.

Meeting with the aggregate on a regular basis will allow the nurse to make an in-depth assessment. Determining sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., distribution of age, sex, and race) may help the nurse ascertain health needs and develop appropriate intervention methods. For example, adolescents need information regarding nutrition, abuse of drugs and alcohol, and relationships with the opposite sex. They usually do not enjoy lectures in a classroom environment, but the nurse must possess skills to initiate small-group involvement and participation. An adult group’s average educational level will affect the group’s knowledge base and its comfort with formal versus informal learning settings. The nurse may find it more difficult to coordinate time and energy commitments if an organization is the focus group, because the aggregate members may be more diverse.

The nurse may gather information about sociodemographic characteristics from a variety of sources. These sources include observing the aggregate, consulting with other aggregate workers (e.g., the factory or school nurse, a Head Start teacher, or the resident manager of a high-rise senior-citizen apartment building), reviewing available records or charts, interviewing members of the aggregate (i.e., verbally or via a short questionnaire), and interviewing a key informant. A key informant is a formal or informal leader in the community who provides data that is informed by his or her personal knowledge and experience with the community.

In assessing the aggregate’s health status, the nurse must consider both the positive and negative factors. Unemployment or the presence of disease may suggest specific health problems, but low rates of absenteeism at work or school may suggest a need to focus more on preventive interventions. The specific aggregate determines the appropriate health status measures. Immunization levels are an important index for children, but nurses rarely collect this information for adults. However, the nurse should consider the need for influenza and/or pneumonia vaccines with the elderly. Similarly, the nurse would expect a lower incidence of chronic disease among children, whereas the elderly have higher rates of long-term morbidity and mortality.

The aggregate’s suprasystem may facilitate or impede health status. Different organizations and communities provide various resources and services to their members. Some are obviously health related, such as the presence or absence of hospitals, clinics, private practitioners, emergency facilities, health centers, home health agencies, and health departments. Support services and facilities such as group meal sites or Meals on Wheels (MOW) for the elderly and recreational facilities and programs for children, adolescents, and adults are also important. Transportation availability, reimbursement mechanisms or sliding-scale fees, and community-based volunteer groups may determine the use of services. An assessment of these factors requires researching public records (e.g., town halls, telephone directories, and community services directories) and interviewing health professionals, volunteers, and key informants (i.e., someone who is familiar with the community) in the community. The nurse should augment existing resources or create a new service rather than duplicating what is already available to the aggregate.

A literature review is an important means of comparing the aggregate with the norm. For example, children in a Head Start setting, day care center, or elementary school may exhibit a high rate of upper respiratory tract infections during the winter. The nurse should review the pediatric literature and determine the normal incidence for this age range in group environments. Further, the nurse should research potential problems in an especially healthy aggregate (e.g., developmental stresses for adolescents or work or family stresses for adults) or determine whether a factory’s experience with work-related injury is within an average range. Comparing the foregoing assessment with research reports, statistics, and health information will help determine and prioritize the aggregate’s health problems and needs.

The last phase of the initial assessment is identifying and prioritizing the specific aggregate’s health problems and needs. This phase should relate directly to the assessment and the literature review and should include a comparative analysis of the two. Most important, this step should reflect the aggregate’s perceptions of need. Depending on the aggregate, the nurse may consult the aggregate members directly or interview others who work with the aggregate (e.g., a Head Start teacher). Interventions are seldom successful if the nurse omits or ignores the clients’ input.

During the needs assessment, four types of needs should be assessed. The first is the expressed need or the need expressed by the behavior. This is seen as the demand for services and the market behavior of the targeted population. The second need is normative, which is the lack, deficit, or inadequacy as determined by expert health professionals. The third type of need is the perceived need expressed by the audience. Perceived needs include the population’s wants and preferences. The final need is the relative need, which is the gap showing health disparities between the advantaged and disadvantaged populations (Issel, 2009).

Finally, the nurse must prioritize the identified problems and needs to create an effective plan. The nurse should consider the following factors when determining priorities:

• Number of individuals in the aggregate affected by the health problem

• Severity of the health need or problem

• Availability of potential solutions to the problem

• Practical considerations such as individual skills, time limitations, and available resources

In addition, the nurse may further refine the priorities by applying a framework such as Maslow’s (1968) hierarchy of needs (i.e., lower-level needs have priority over higher-level needs) or Leavell and Clark’s (1965) levels of prevention (i.e., primary prevention may take priority for children, whereas tertiary prevention may take higher priority for the elderly).

Assessment and data collection are ongoing throughout the nurse’s relationship with the aggregate. However, the nurse should proceed to the planning stage once the initial assessment is complete. It is particularly important to link the assessment stage with other stages at this step in the process. Planning should stem directly and logically from the assessment, and implementation should be realistic.

An essential component of health planning is to have a strong level of community involvement. The nurse is responsible for advocating for client empowerment throughout the assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation phase of this process. Community organization reinforces one of the field’s underlying premises as outlined by Nyswander (1956): “Start where the people are.” Moreover, Labonte (1994) stated that the community is the engine of health promotion and a vehicle of empowerment. He describes five spheres of an empowerment model, that focus on the following levels of social organization: interpersonal (personal empowerment), intragroup (small-group development), intergroup (community collaboration), interorganizational (coalition building), and political action. Attention to collective efforts and support of community involvement and empowerment, rather than focusing on individual efforts, will help ensure that the outcomes reflect the needs of the community and truly make a difference in people’s lives.

Labonte’s (1994) multilevel empowerment model allows us to consider both macro-level and micro-level forces that combine to create both health and disease. Therefore, it seems that both micro and macro viewpoints on health education provide nurses with multiple opportunities for intervention across a broad continuum. In summary, health education activities that have an “upstream” focus examine the underlying causes of health inequalities through multilevel education and research. This allows nurses to be informed by critical perspectives from education, anthropology, and public health (Israel et al., 2005).

Successful health programs rely on empowering citizens to make decisions about individual and community health. Empowering citizens causes power to shift from health providers to community members in addressing health priorities. Collaboration and cooperation among community members, academicians, clinicians, health agencies, and businesses help ensure that scientific advances, community needs, sociopolitical needs, and environmental needs converge in a humanistic manner.

Planning

Again, the nurse should determine which problems or needs require intervention in conjunction with the aggregate’s perception of its health problems and needs, and based on the outcomes of prioritization. Then the nurse must identify the desired outcome or ultimate goal of the intervention. For example, the nurse should determine whether to increase the aggregate’s knowledge level and whether an intervention will cause a change in health behavior. It is important to have specific and measurable goals and desired outcomes. This will facilitate planning the nursing interventions and determining the evaluation process.

Planning interventions is a multistep process. First, the nurse must determine the intervention levels (e.g., subsystem, aggregate system, and/or suprasystem). A system is a set of interacting and interdependent parts (subsystems), organized as a whole with a specific purpose. Just as the human body can be viewed as a set of interacting subsystems (e.g., circulatory, neurological, integumentary), a family, a worksite, or a senior high-rise can also be viewed as a system. Each system then interacts with, and is further influenced by, its physical and social environment, or suprasystem (for example, the larger community).

Second, the nurse should plan interventions for each system level, which may center on the primary, secondary, or tertiary levels of prevention. These levels apply to aggregates, communities, and individuals. Primary prevention consists of health promotion and activities that protect the client from illness or dysfunction. Secondary prevention includes early diagnosis and treatment to reduce the duration and severity of disease or dysfunction. Tertiary prevention applies to irreversible disability or damage and aims to rehabilitate and restore an optimal level of functioning. Plans should include goals and activities that reflect the identified problem’s prevention level.

Third, the nurse should validate the practicality of the planned interventions according to available personal as well as aggregate and suprasystem resources. Although teaching is often a major component of community health nursing, the nurse should consider other potential forms of intervention (e.g., personal counseling, policy change, or community service development). Input from other disciplines or community agencies may also be helpful. Finally, the nurse should coordinate the planned interventions with the aggregate’s input to maximize participation.

Goals and Objectives

Development of goals and objectives is essential. The goal is generally where the nurse wants to be, and the objectives are the steps needed to get there. Measurable objectives are the specific measures used to determine whether or not the nurse is successful in achieving the goal. The objectives are instructions about what the nurse wants the population to be able to do. In writing the objectives, the nurse should use verbs and include specific conditions (how well or how many) that describe to what degree the population will be able to demonstrate mastery of the task.

The objectives may be used to later measure learning outcomes, but the objectives need to be measurable. Objectives may also be referred to as behavioral objectives or outcomes because they describe observable behavior rather than knowledge. An example of the goals and measurable objectives for a city with a high rate of childhood obesity is shown in Box 7-3.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree