Faith Community Nursing

Beverly Cook Siegrist

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Understand the potential role of faith communities in improving the health of Americans.

2. Describe the philosophy and historical basis of faith community nursing.

3. Define the roles, functions, and education of the faith community nurse.

4. Discuss faith communities as clients of the community health nurse.

7. Apply the nursing process to a case study related to a faith community practice.

Key terms

CIRCLE Model of Spiritual Care

coordinator of volunteers

developer of support groups

facilitator

faith community

Granger Westberg

health advocate

health educator

integrator of health and healing

personal health counselor

referral agent

spiritual distress

spirituality

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

Nurses seem to have one foot in the sciences and one in the humanities; one foot in the spiritual world and one in the physical one.…they [nurses] have insight into the human condition. (Maginnis and Associates, 1993, p. 1)

The purpose of this chapter is to present an overview of faith community nursing and to explore the challenges of providing nursing care to faith communities. On the basis of centuries-old philosophies from churches and religious groups, nurses are applying the science of nursing and caring to address the biopsychosocial health needs of individuals and groups in church congregations and faith communities across the country. The following scenarios illustrate models of faith community nursing found in the United States and suggest the unique ways that parish nurses provide nursing care.

The three clinical examples illustrate how faith nursing is evolving in the United States. From beginning as fewer than a dozen nurses in Chicago, the practice now includes thousands of nurses in more than twenty-three countries (International Parish Nurse Resource Center [IPNRC], 2009b). The growing number of registered nurses (RNs) in parish nursing documents this practice as a significant role for the community health nurse. Community health nursing has evolved from early church efforts to provide care for the sick and disenfranchised. Modern parish nursing focuses on the global health and wellness issues of all people and has its roots in more recent efforts to encourage the reemergence and blending of health care roles into the healing ministry of faith communities (Patterson, 2004; Solari-Twadell and McDermott, 1999).

Faith communities: role in health and wellness

Former President Jimmy Carter, faculty and founding member of Strong Partners Interfaith Health Program at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, understands the importance of faith communities for Americans. President Carter is quoted on the Interfaith Health Program website (http://www.ihpnet.org):

What if churches, mosques, and temples worked together to improve the health of their communities? If faith groups adopted one small area and made sure that every single child were immunized…that every person had a basic medical exam…that every woman who became pregnant would get prenatal care? Are these possible? We believe the answer is yes. (Interfaith Health Program, 2005)

Throughout history, church communities have provided care for the indigent and disenfranchised, meeting basic human needs of food and clothing and basic health care. The majority of the world’s populations belong to organized faith communities. Approximately one third of the people in the world identify themselves as Christians (2 billion), followed by Muslims (1.5 billion), Hindus (900 million), and Buddhists (380 million) (IPNRC, 2009b). All of these religions have traditions and rituals related to health and healing, including specific prayers and practices. Some of the religions give specific guidelines for ministering to the ill, homebound, or dying members. All of the major religions describe the relationship between health, healing, and wholeness. The Old Testament discusses Shalom, or God’s desire for health and wholeness for the earth and its people. The New Testament documents the healing activities of Jesus, restoring health to people. The Talmud describes the importance of maintaining physical health and vigor so that Jewish people will understand God’s will in their lives. Followers of Buddhism believe that healing and recovery are promoted by awakening to the teachings of Buddha (IPNRC, 2009b).

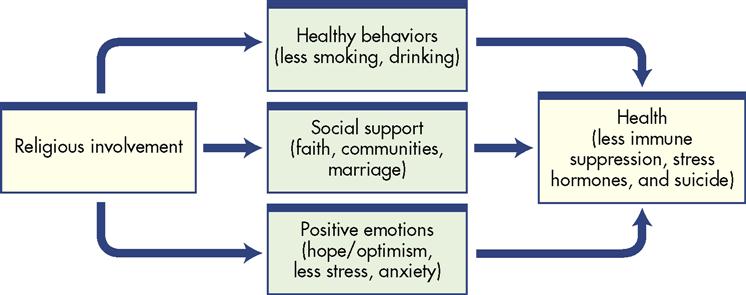

Williams and Sternthal (2007) completed a meta-analysis of studies related to spirituality, religion, and health. In 17 studies, individuals who reported intrinsic religion (internalized or regularly practiced) and regular attendance at a religious service reported decreased stress. In 147 studies, it was found that there was an inverse relationship between religiosity and depression. The authors found evidence in another 49 studies that indicated people who practiced religious coping had lower levels of anxiety, depression, and stress and coped more positively with many chronic diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hypertension, and cancer. One reason for this variance may be that the people who reported the highest level of religious involvement also reported practicing healthier lifestyles, including exercising more and smoking less (Tsuang, Williams, and Lyons, 2002; Myers, 2004). Eckersley (2007) suggests that “religion provides things that are good for health and wellbeing, including social support, existential meaning, a sense of purpose, a coherent belief system and a clear moral code” (p. S54). Myers (2004) and Koenig and George (2004) suggest that faith communities contribute to the well-being of their members through support, prayer, and providing a sense of hope. The importance of stress management in health promotion and disease management is well documented. The interaction and possible explanation for the positive correlation between religious involvement and health is visualized in Figure 32-1.

Organized religions are attempting to meet the needs of members in many nontraditional ways including exploring Internet church services, developing support groups, and including modern music and drama in traditional worship services to improve intergenerational communication. FCNs, because of their educational preparation and goals, are ideal health professionals to ensure that the health information provided in congregations is accurate and accessible. Parish nurses also understand the importance of spirituality in health and healing. The role of the FCN therefore complements the ministry of health found in faith communities.

Foundations of faith community nursing

Reverend Granger Westberg, a Lutheran minister, is considered the founder of the modern FCN movement. Westberg, educated as a chaplain and minister, worked with nurses in hospitals, medical schools, and church communities. Impressed with the nurse’s perspective of health and wholeness in viewing the physical, emotional, and spiritual challenges of human illness, he described parish nursing as the culmination of his lifelong work in relating theology and health care. In 1984, he first proposed a parish nurse program to Lutheran General Hospital (LGH) in Chicago, Illinois. Westberg envisioned a partnership between the hospital and all church congregations in the hospital’s community. He proposed that participating churches would make contributions to fund a nurse’s salary and identified seven roles the nurse could use to provide services to faith communities (Hickman, 2007; O’Brien, 2003; Patterson, 2004).

In 1985, six FCNs were hired in the Chicago area. Initially, LGH and the participating churches’ contributions primarily funded the nurses’ salaries. The churches assumed increasing responsibility for the nurses’ salaries over a 4-year period. Westberg supported the development of an FCN training program and required the nurses to participate in a weekly educational session. Teaching chaplains, nurse educators, and physicians led the sessions, which were aimed at enhancing nurses’ skills in counseling, education, spiritual assessment, and related nursing interventions. The meetings evolved into an ongoing support group for the nurses as they developed the faith community programs and identified self-care needs. LGH continued to provide FCN leadership through the IPNRC. Located in Park Ridge, Illinois, the center offered education, development guidance, and contact with parish nurses nationally and internationally. In 2001, ownership of the IPNRC moved from the Lutheran-rooted Advocate Health Care System to the Deaconess Foundation of St. Louis, Missouri. The Deaconess ministries in the United States have their roots in the Deaconess service movement founded in Germany in the mid-1800s. Deaconess has been involved in faith community nursing since the late 1980s and, as the Deaconess Parish Nurse Ministry, is a leader in the specialty in the United States. The Deaconess Parish Nurse Ministries is the current parent organization of the IPNRC (IPNRC, 2009a; Westberg, 2007).

In 1998, the American Nurses Association (ANA), in collaboration with the newly formed Health Ministries Association, Parish Nurse Division, published the first Scope and Standards of Parish Nurse Practice. This was a landmark publication for parish nurses, officially recognizing the practice as a nursing specialty. ANA revised the standards in 2005, providing a clearer definition of the practice including advanced nursing practice and changing the name of the specialty from parish nurse to FNC. While acknowledging the importance of the Judeo-Christian basis of the practice, the authors believed the change better reflected the diversity now found in the specialty. The IPNRC (2009b) reports that faith community nursing is now practiced in more than 23 countries including Australia, Bahamas, Canada, England, Ghana, Kenya, Korea, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, New Zealand, Nigeria, Pakistan, Palestine, Scotland, Singapore, South Africa, Swaziland, Ukraine, United States, Wales, Zambia, and Zimbabwe serving Muslim, Jewish, and Christian faith communities. Many FCNs continue to identify themselves as parish nurses in deference to Dr. Westberg and the origins of the practice. For this reason, the terms are used interchangeably in the literature and at conferences. Other FCNs may be known as congregational nurses or church nurses, choosing to identify themselves in a manner most accepted by the individual faith communities.

Solari-Twadell and McDermott (1999) and Westberg (1990) described the philosophical basis of parish nursing as encompassing the following five key elements:

1. The spiritual dimension is central to the practice.

2. The role balances nursing science and technology with service and spiritual care.

These beliefs direct the parish nurse in planning nursing care and defining health not only as wellness but also as wholeness of body and spirit. They also emphasize spiritual health as a motivating factor in seeking wellness care, participating in education, and enhancing self-care capabilities (Hickman, 2007; Patterson, 2004; Smith, 2003). The IPNRC (2009a) identifies a vision that “every faith community in the future will have access to a FNC.”

A review of the historical foundations of community health nursing practice describes the significance of the church in early health care. In the Bible, the book of Romans (16:1-2) describes the early works of Phoebe, who is considered to be the first visiting nurse. In his 1786 sermon “On Visiting the Sick,” John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist church, directed his believers to visit the sick to convey God’s grace to others (Wesley, 1986). These selected examples illustrate the significance of the church as an influence on health and healing. The histories of all religions provide similar examples. The reemergence of these basic beliefs in health, healing, and spirituality are moving the church toward assisting members in wholeness; this is evidenced by the growing number of health ministries and FCN programs found in churches throughout the nation (Hickman, 2007; Patterson, 2004). The defining characteristics and roles of the FCN in any setting come from these philosophical foundations.

The current mission statement for parish nurses was developed and approved in 2000 by more than 600 attendees at the fourteenth annual Westberg Symposium.

Parish nursing is the intentional integration of the practice of faith with the practice of nursing so that people can achieve wholeness in, with, and through communities of faith in which the parish nurse serves. Parish nurses educate, advocate, and activate people to take positive action regarding wellness, prevention, appropriate treatment of illness, and social and spiritual connections with God, members of their congregations, and their wider community. (Patterson, 2004, p. 32)

Roles of the faith community nurse

The FCN practice focuses on health promotion and wellness. It is based on a holistic nursing practice that holds the spiritual dimension central to health and healing within the context of the faith community. In the nursing process, the FCN improves the health of a faith community by implementing interrelated roles including those of health educator, personal health counselor, referral agent, health advocate, coordinator of volunteers, developer of support groups, and integrator of health and healing (Hickman, 2007 IPNRC, 2009a).

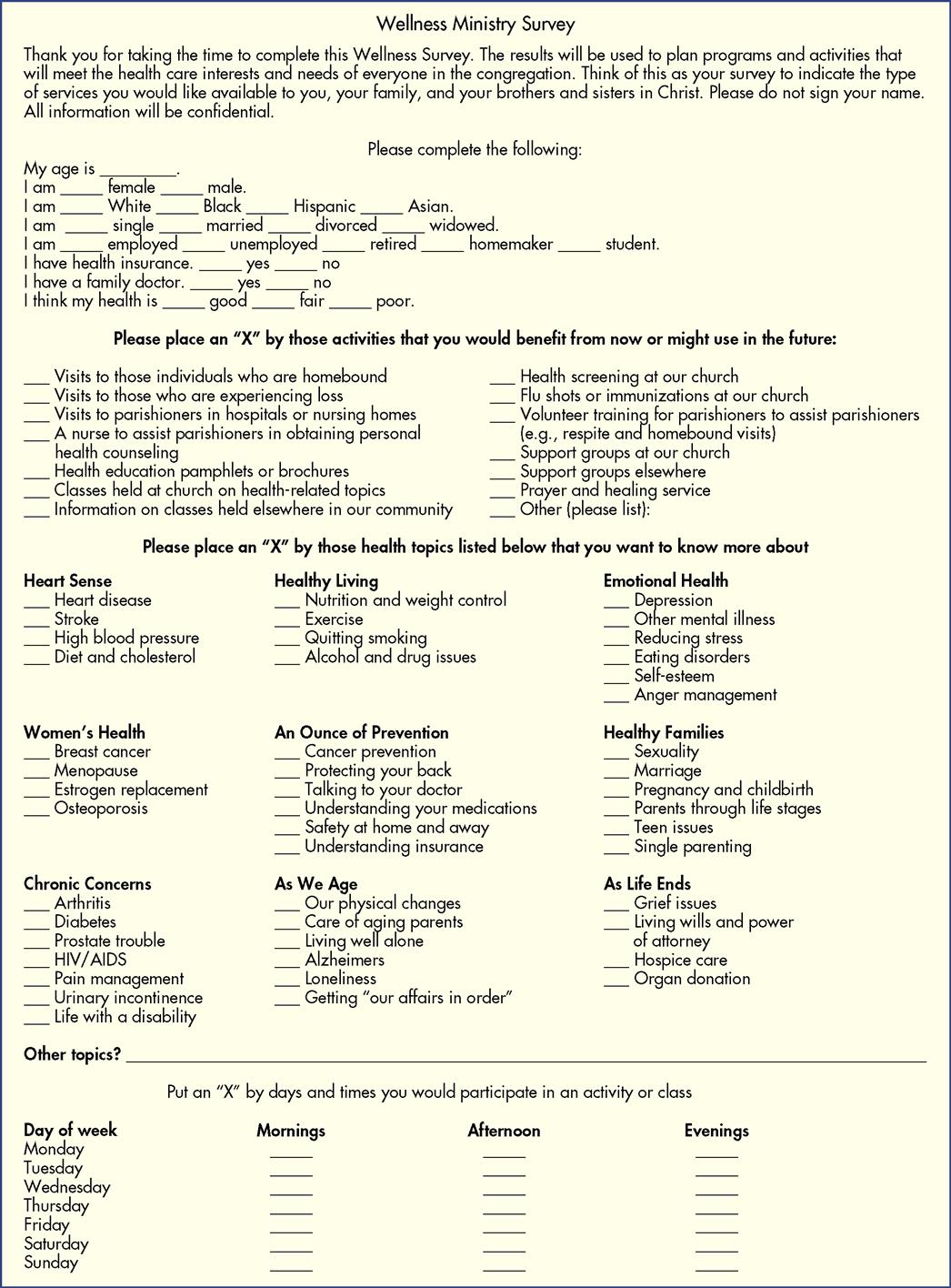

As a health educator, the FCN provides or coordinates educational offerings for people of all ages and developmental stages. The educational efforts may target lifestyles, values, and wellness and incorporate the spiritual aspects of individual and community well-being. The educator role includes educating the church leaders and members about the roles and purposes of a parish nurse. Educational efforts are planned based on the church community’s priorities and Healthy People 2020 (USDHHS, 2009). Because the faith community membership includes people across the life span, church-based educational programs can address all ten major health indicators (IPNRC, 2009a; King and Tessaro, 2009). Early in the development of a parish nurse program, and periodically thereafter, the parish nurse should assess the health status and needs of the congregation members to determine educational priorities. Figure 32-2 presents an example of an adult congregational health and wellness survey. The FCN should complete an assessment on each population group served by the congregation and include children grouped by developmental stages. Examples of educational efforts are teaching cardiopulmonary resuscitation to new mothers; teaching signs and symptoms of hypertension and stroke to adults in the congregation; educating lay church ministers in the signs and symptoms of acute illness when visiting homebound individuals; and teaching basic health and safety to school-aged children. With increasing frequency, FCNs are implementing comprehensive wellness programs. One such program is “Get My People Going” developed by the IPNRC. It provides an 8-week healthy lifestyle program based on the Exodus story that includes exercise, nutrition, and community support (IPNRC, 2008).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Healthy People 2020

Healthy People 2020