Theory in Research

Key terms

Concept

Construct

Hypothesis

Levels of abstraction

Operationalize

Proposition

Theory

Theory-generating

Theory testing

Think of a particular field of inquiry or a particular research question or query of interest to you, and ask yourself the following two questions:

What do we know about this phenomenon?

What do we know about this phenomenon?

What theories have been developed to explain or understand the phenomenon?

What theories have been developed to explain or understand the phenomenon?

You will want to keep asking these basic questions as you engage in the research process and explore different problems of interest. For each research question or query that you pose, the way in which you answer these basic questions will largely determine the type of research actions (e.g., design strategy, analysis, and reporting) that you will implement. As discussed in previous chapters, the level of knowledge and theory development in a particular field shapes how a research question or query is framed and a design strategy is implemented. Theory has a critical role in both experimental-type and naturalistic research as well as in integrated methodologies.

Why is theory important?

When people hear the word “theory,” they often feel overwhelmed and assume that the term is not relevant to their daily lives or is too abstract and complicated to understand. However, think about how difficult life would be without theory. Theory informs us each day in many aspects of our lives, from knowing how to prepare for the weather to guiding our professional practice. For example, predicting the weather is based on existing theory. The meteorologist looks at present weather conditions and past weather patterns and makes a prediction in the form of a forecast.

In health and human service delivery, you make a decision about which intervention to use with a patient or client on the basis of theory. You use a theory to guide your decisions, even though you may not be fully cognizant that you are actually doing so.

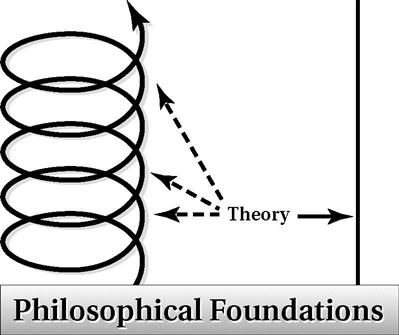

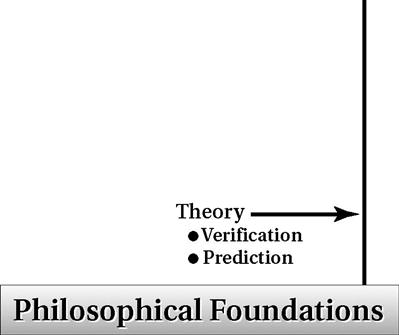

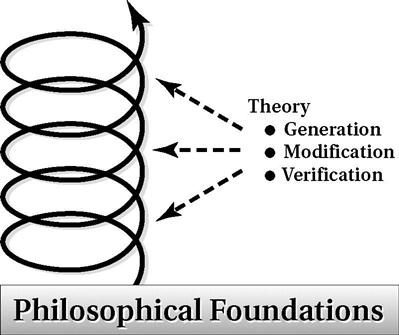

As discussed in Chapter 1, a primary purpose of research is directly linked to theory. In experimental-type designs, one primary purpose of research is to test theory using deductive processes. In naturalistic inquiry, the purpose is usually to generate theory using induction or abduction. This chapter introduces another important aspect in the relationship between research and theory: that is, you must have a theoretical framework to conduct adequate research. This is the primary point of this chapter.

As discussed throughout this text, thinking and action processes are equally important parts of research. Critical to the thinking processes are the set of human ideas that can be organized to understand human experience and phenomena. As described later in this chapter, these ideas are theories or parts of theories. Even though we may not realize it, theory frames how we ask, look at, and answer questions. Theory provides conceptual clarity and the capacity to connect the new knowledge obtained through data collection action processes to the vast body of knowledge to which it is relevant. Without theory, we do not have conceptual direction. Data that are derived without being conceptually embedded in theoretical contexts do not advance our understanding of human experience and ultimately are not useful. Remember, “usefulness” is an important component of our definition of research. Of importance is that theory helps a researcher see the forest instead of just a tree. That is, it helps the researcher make sense of details and place them within a larger context. If we only focus on a single tree or detail, we lose sense of the whole and how that one detail or observation functions or relates to the larger context.

Let us examine more closely why theory must inform or shape research actions by considering the meaning and use of common terms such as “race” and “ethnicity.”

What is theory?

By now you might be asking, “So what is theory?” Definitions range from traditional views of theory as systems to organize, describe, and predict a single reality; to abstract systems of language symbols that provide multiple interpretations and ideas of phenomena; to ideological foundations for social action.3

We draw on Kerlinger’s classic definition of theory because we believe it is the most comprehensive and useful for investigators and students of research. Kerlinger defines theory as “a set of interrelated constructs, definitions, and propositions that present a systematic view of phenomena by specifying relations among variables, with the purpose of explaining or predicting phenomena.”4 In this definition, theory is a set of related ideas that has the potential to explain or predict human experience in an orderly fashion, and it is based on data. The theorist develops a structural map of what is observed and experienced in an effort to promote understanding and facilitate the ability to predict outcomes under specific conditions. Through deductive research approaches or empirical investigations, theories are either supported and verified or refuted and falsified. Through inductive approaches, theories are incrementally developed to explain and give order to observations of human experience.

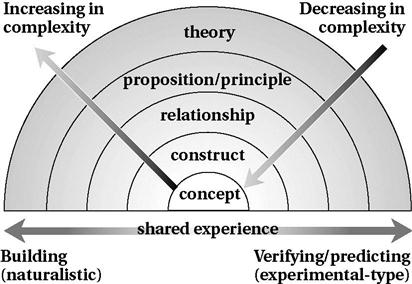

As implied in Kerlinger’s definition, four interrelated structural components are subsumed under theory and range in degree, or level, of abstraction. Although numerous taxonomies for the parts of a theory have been proposed,5 we suggest that the four basic structures of theory are concepts, constructs, relationships, and propositions or principles. Let us first examine the meaning of abstraction and then discuss each level.

Levels of Abstraction

Abstraction often conjures up a vision of the ethereal, the “not real.” In this book, however, we use the term “abstraction” as it relates to theory development, to depict a symbolic representation of shared experience. For example, if we all see a form that has fur, a tail, four legs, and barks, we name that observation a “dog.” We have shared in the visual experience and have created a symbol (the word “dog”) to name our sensory experience.

All words are merely symbols to describe and communicate experience. Words are only one form of abstraction; different words represent different levels of abstraction, and a single word can represent multiple levels of abstraction.

Figure 6-1 displays the four levels of abstraction within theory and their interrelationships. Shared experience is the foundation on which abstraction is built. It is important to recognize that we do not use the term “reality” as the foundation. Reality implies that there is only one viewpoint from which to build the basic elements of a theory. In contrast, this text is based on the premise that humans experience multiple realities and multiple perspectives about the nature of reality. As such, levels of abstraction must be built on shared experience, defined as the consensus of what we obtain through our senses. For experimental-type researchers who work deductively, shared experience is usually thought of as sense data, or that which can be reduced to observation and measurement. For researchers working inductively and abductively in the naturalistic tradition, shared experience may include meanings and interpretations of human experience.

Let us use the example of the “furry being with four legs and a tail that barks” to illustrate the multiple meanings that can be attributed to shared experience. Shared experience tells each of us that this is a dog, but the word “dog” may also carry with it diverse meanings, such as fear or happiness.

Each type of experience is equally important to acknowledge, as are the different meanings attributed to a single word.

Concepts

As depicted in Figure 6-1, a concept is the first level of abstraction and is defined as a single, first-order symbolic representation of an observable or experienced referent.6 By first order, we mean that there is no abstract level between shared experience and concept. Concept is directly inferred from observations and other sense data. Concepts are the basic building blocks of communication because they provide us with the means to tell our experiences and ideas to one another. Without concepts, we would not have language.6 In the case of the “furry being,” the word “dog” can function as a concept. At this basic level of abstraction, the term “dog” describes an observation shared by many. The words “furry,” “tail,” “four legs,” and “bark” are also concepts because they are directly sensed.

In experimental-type research, concepts are selected before a study is started and are defined to permit direct measurement or observation. In naturalistic research, concepts are derived primarily through direct observations and continual engagement with the phenomenon of interest in the context in which it occurs.

Constructs

A construct, the next level of abstraction, does not have an observable or a directly experienced referent in shared experience. Meanings become important to consider at this level of abstraction, because two individuals who articulate the same construct may attribute disparate meanings to it. If we look again at the term dog as a construct rather than a concept, the word may mean “fear” to some and “happiness” to others. Although we stated earlier that dog is a concept, in this case, “dog” functions as a construct because what is observable is not the communicated meaning. Rather, the meaning of the term takes on the feelings evoked by “dog,” such as fear or happiness.

Fear and happiness are also examples of constructs. What may be observed are the behaviors associated with fear or happiness, that is, someone who sweats, shakes, and turns pale at the site of a dog or someone who smiles, approaches, and pets the dog, respectively. These observations of both feelings are synthesized into the constructs of fear and happiness. Thus, fear and happiness are not directly “observed” but are surmised by observations of human behavior and are based on a constellation of behavioral concepts.

Categories provide additional examples of constructs. The category of “mammal” or “canine” is an example of a construct. Although each category or construct is not directly observable, it is composed of a set of concepts that can be observed.

Other examples of constructs relevant to health and human service inquiry include quality of life, health, wellness, life roles, rehabilitation, poverty, illness, disability, functional status, and psychological well-being. Although not directly observable, each is made up of parts or components that can be observed or submitted to measurement. Think about the construct of “quality of life”; which concepts is this construct composed of? Examples of concepts that compose quality of life can include health status, self-efficacy, or positive mood. If you consider that even this relatively low level of abstraction is multifaceted, you can begin to understand why health and human service research is so complex.

Relationships

So far, we have been discussing single-word symbols or units of abstraction. At the next level of abstraction, single units are connected to form a relationship. A relationship is defined as an association of two or more constructs or concepts. For example, we may suggest that the size of a dog is related to the level of fear that a person experiences. This relationship has two constructs, “size” and “fear,” and one concept, “dog.” Think about the construct of “quality of life” and consider the concepts it is composed of and their relationship as it is relevant for a specific population you work with or have an interest in (e.g., elderly, children with mobility impairments, individuals with spinal cord injury, prisoners). For example, research suggests that quality of life in older adults is related to the extent to which functional limitations curtail activity participation. Thus, the relationship between two concepts, disability and activity restriction, is critical to the construct of quality of life as it pertains to older adults living at home.

Propositions (Principles)

A proposition is the next level of abstraction. A proposition, or principle, is a statement that governs a set of relationships and gives them a structure. For example, a proposition suggests that fear of large dogs is caused by negative childhood experiences with large dogs. This proposition describes the structure of two sets of relationships: (1) the relationship between the size of a dog and fear and (2) the relationship between childhood experiences and the size of dogs. It also suggests the direction of the relationship and the influence of each construct on the other. Let’s revisit the construct of quality of life. Can you develop a proposition based on the relationship between functional difficulty and activity limitation? One proposition may be that quality of life is affected by the extent to which having a functional difficulty limits participation in valued activities. That is, having a functional difficulty leads to poor quality of life to the extent that activities one wants to participate in are affected or curtailed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Assume you are a health or human service professional working in a psychiatric hospital. A new member comes to your group therapy session with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Theoretically, you know that this diagnosis is associated with a set of symptoms and behaviors, particularly self-degradation, faulty thinking, and melancholia. On the basis of this cognitive-behavioral theoretical understanding of the symptoms, as well as the prediction of the individual’s behavioral outcomes, you approach this client with support and engage him or her in a cognitive-behavioral program in which self-degrading ideation is incrementally decreased. Consider the role of theory in your clinical decision making. Without the theory, you would not have known how to work skillfully with this client.

Assume you are a health or human service professional working in a psychiatric hospital. A new member comes to your group therapy session with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Theoretically, you know that this diagnosis is associated with a set of symptoms and behaviors, particularly self-degradation, faulty thinking, and melancholia. On the basis of this cognitive-behavioral theoretical understanding of the symptoms, as well as the prediction of the individual’s behavioral outcomes, you approach this client with support and engage him or her in a cognitive-behavioral program in which self-degrading ideation is incrementally decreased. Consider the role of theory in your clinical decision making. Without the theory, you would not have known how to work skillfully with this client. Every 10 years, the U.S. government conducts a national census in which characteristics of individuals, families, and neighborhoods are ascertained by collecting information. Since the 1970s, there has been a significant debate about the need and rationale for recording race and ethnicity.

Every 10 years, the U.S. government conducts a national census in which characteristics of individuals, families, and neighborhoods are ascertained by collecting information. Since the 1970s, there has been a significant debate about the need and rationale for recording race and ethnicity. A theory related to the “furry being” may be that “fear of large dogs derives from childhood experiences.” Therefore the fear can be cured by psychoanalysis that aims to reverse the negative effects of childhood experiences. This theory explains the phenomenon “fear of dogs”; it is verifiable and can lead to prediction. If, through research, we can support a positive relationship between childhood experiences and fear of dogs and the effectiveness of psychoanalysis in reducing that fear, we can predict this relationship in the future and control its outcome.

A theory related to the “furry being” may be that “fear of large dogs derives from childhood experiences.” Therefore the fear can be cured by psychoanalysis that aims to reverse the negative effects of childhood experiences. This theory explains the phenomenon “fear of dogs”; it is verifiable and can lead to prediction. If, through research, we can support a positive relationship between childhood experiences and fear of dogs and the effectiveness of psychoanalysis in reducing that fear, we can predict this relationship in the future and control its outcome.