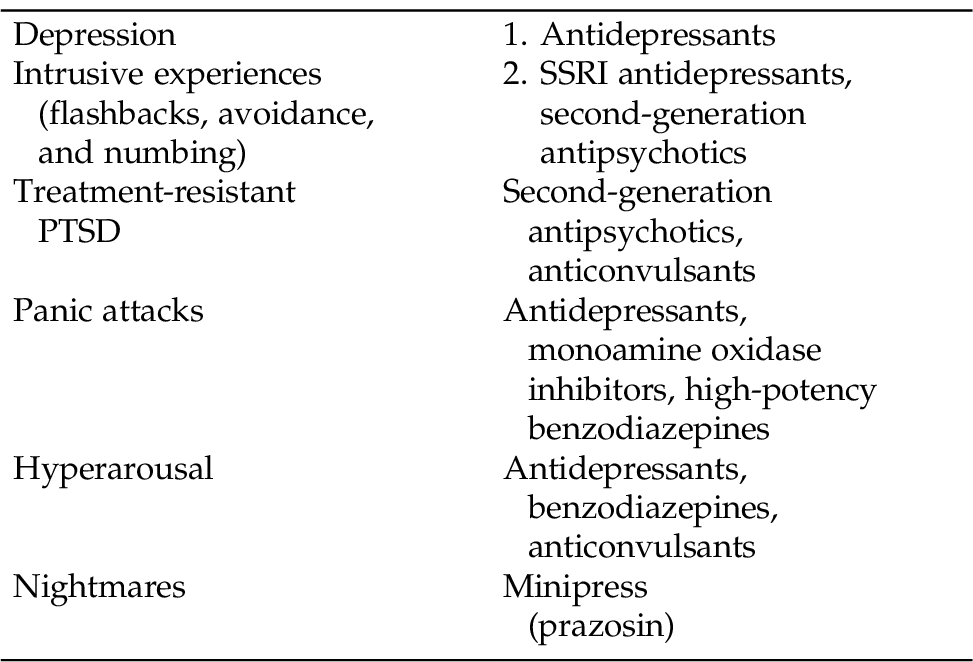

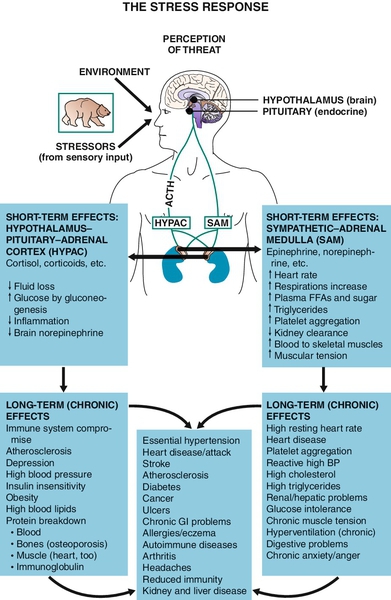

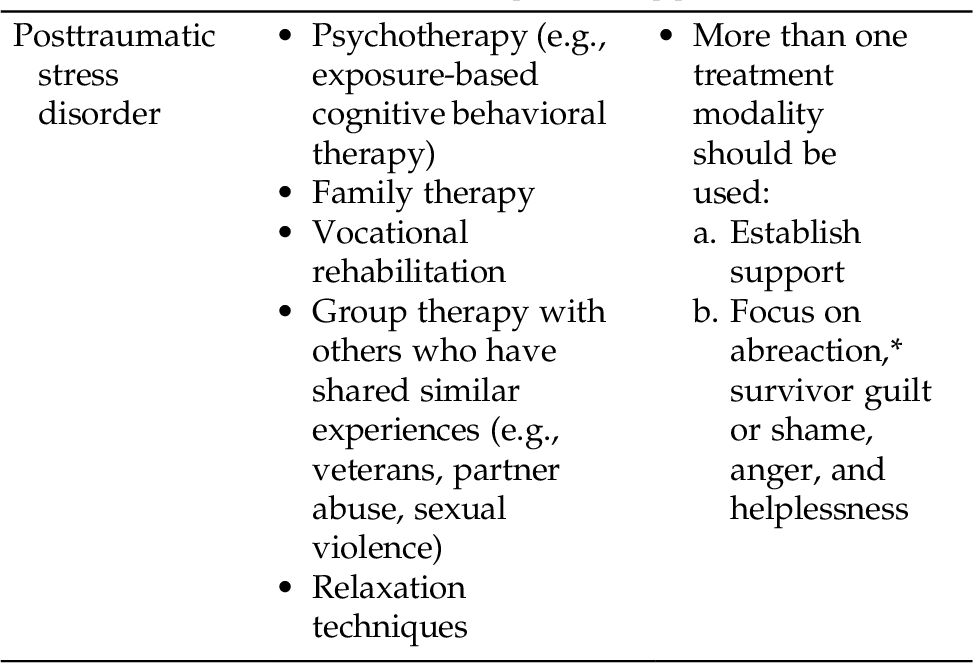

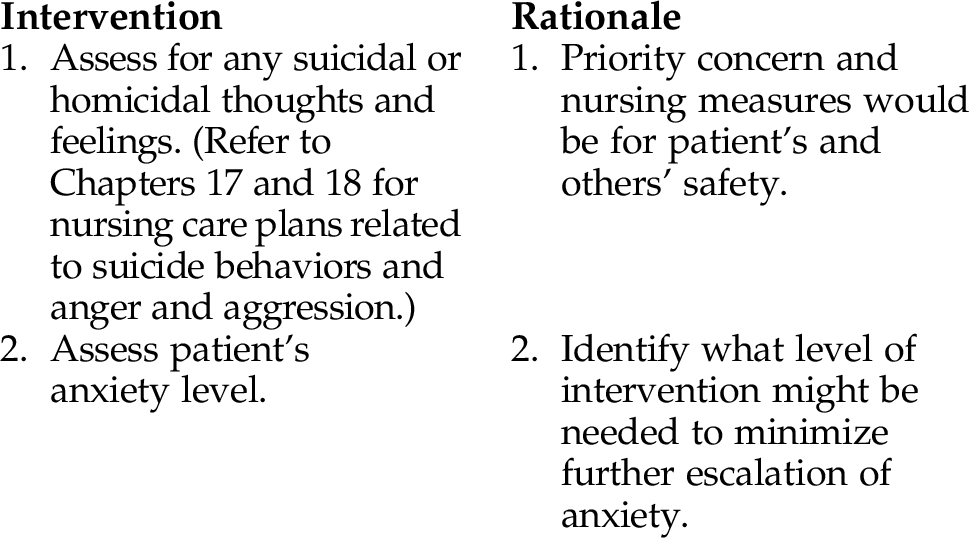

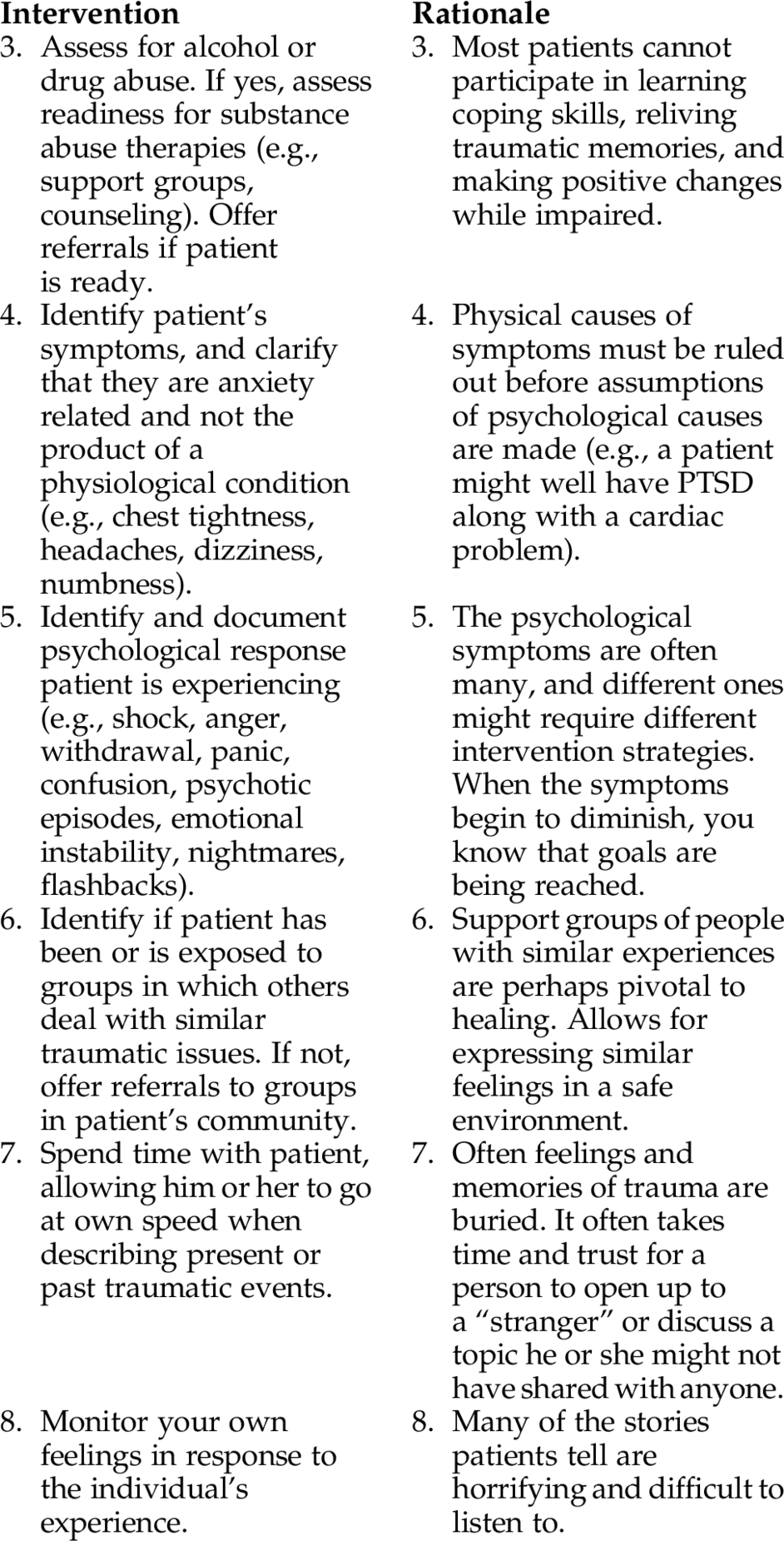

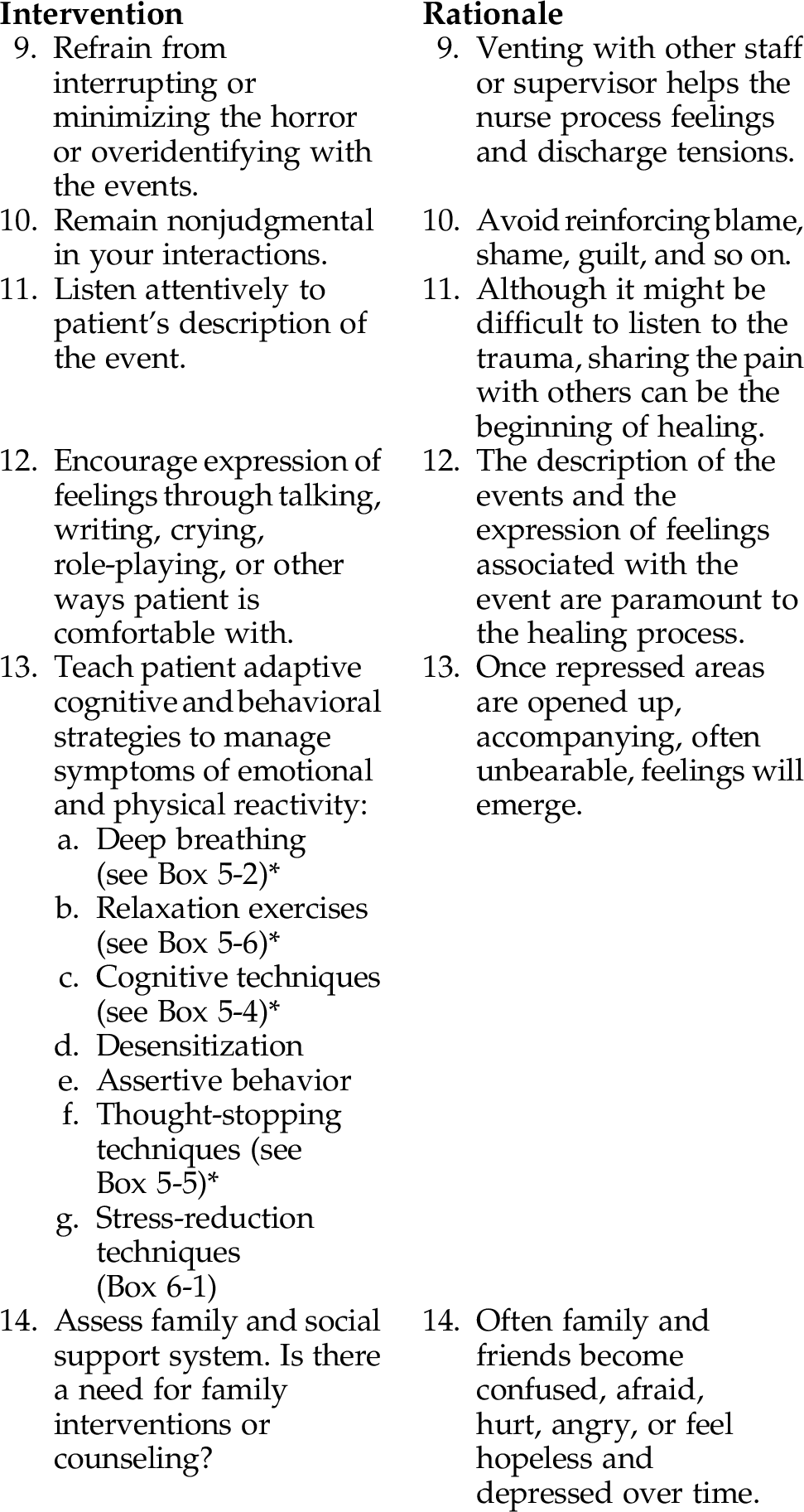

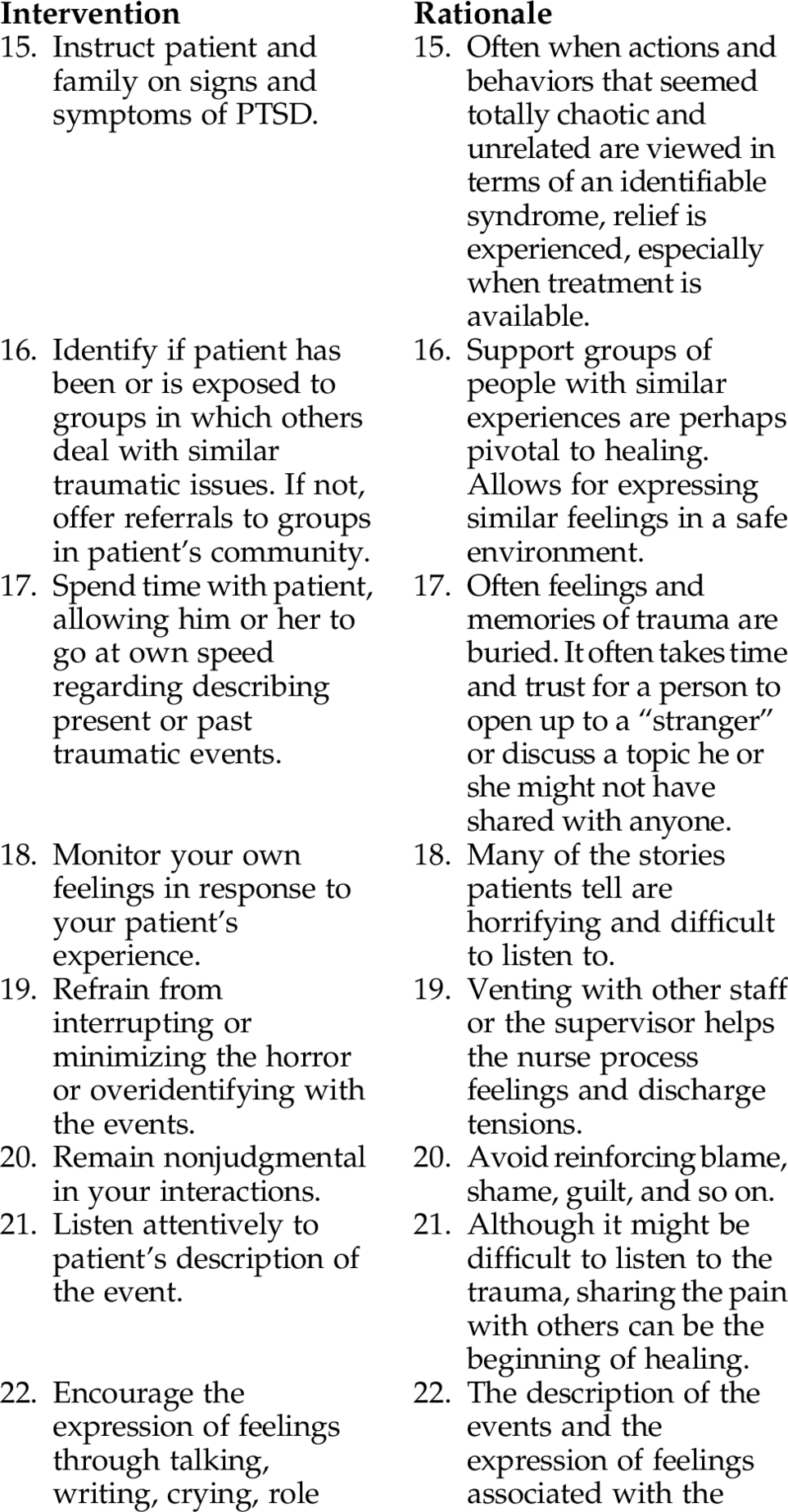

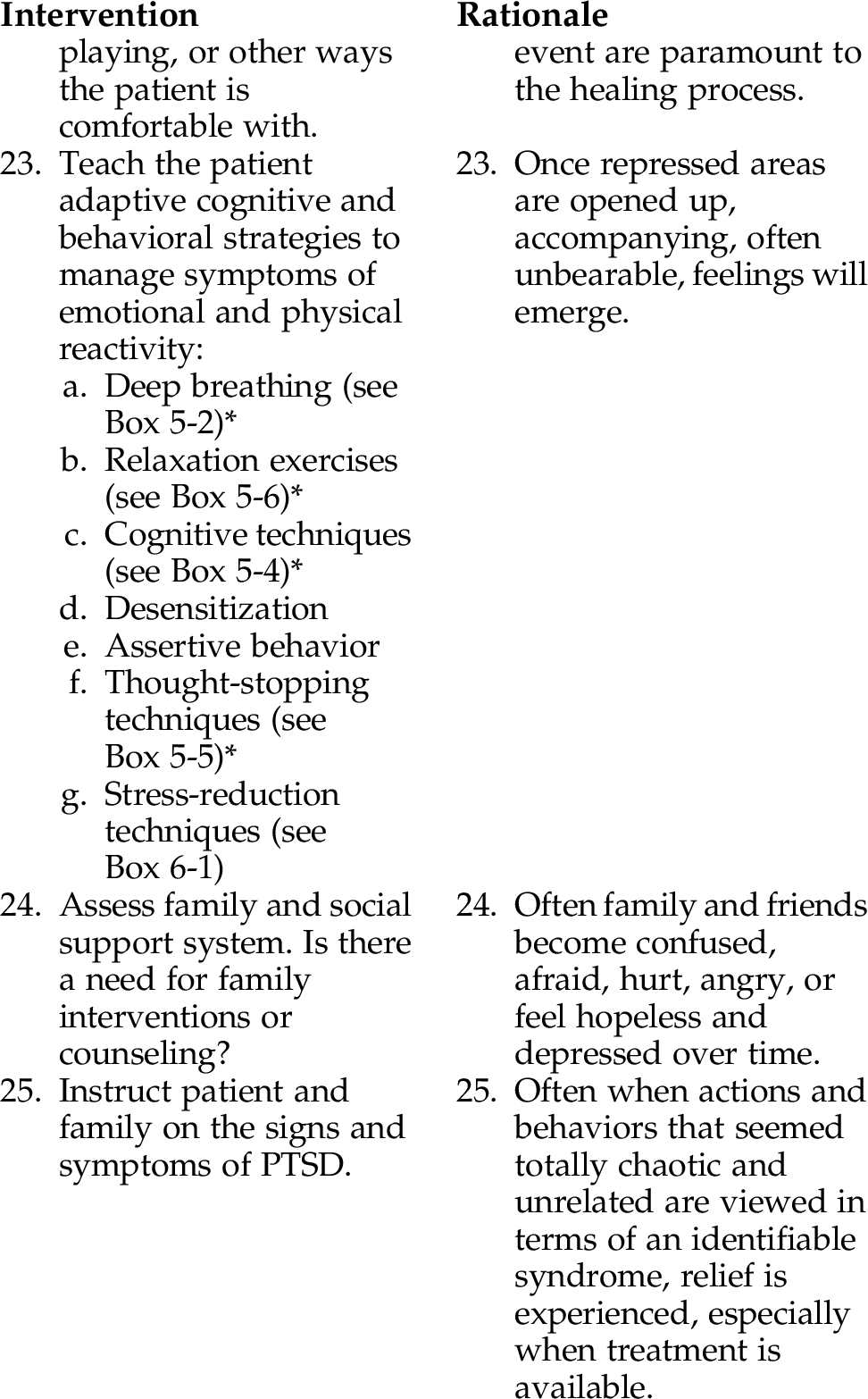

CHAPTER 6 We are all familiar with stress. Some stress is termed “good” stress, or eustress. Eustress is beneficial stress; it motivates people to develop the skills they need to solve problems and meet personal goals. However, it is the distress that causes problems. Distress is a negative experience that can drain our energy. Increased stress and anxiety can trigger depression, cause confusion, and instill helplessness/hopelessness, causing fatigue. When we are faced with the stressful response, our brain responds, signaling all areas of our body. The stress response is also referred to as the “fight or flight response.” The fight or flight response is a survival mechanism by which our body and mind become immediately ready to meet a threat or stressor. A stressor—that which triggers stress—can be real or perceived. Stress can be psychological (e.g., ethnic and religious conflicts occurring globally, terrorism, anxiety, guilt, or joy), or physical (e.g., stressful environment, starvation, loud noises, extreme heat or cold, or other disturbing physical condition). Stress can be psychosocial (e.g., threat to self-esteem, acceptance in a group, social status, and respect). Stress can also be spiritual (such as an existential crisis). When individuals feel “stressed out,” they may have trouble sleeping or eating, experience headaches or back pain, lose interest in favorite activities, feel tense and become irritable, and often feel powerless. When stress is prolonged or people are not able to de-stress, they remain in chronic low levels of stress. The body stays alert for a prolonged period of time. The chemicals produced by the stress response (cortisol, adrenaline, and other catecholamines) can have damaging effects on the body, causing physical diseases including a substantial negative effect on the immune system, leaving individuals vulnerable to autoimmune diseases. Prolonged chronic stress contributes to psychological disorders as well. Repeated trauma or stress not only alters the release of neurotransmitters but also changes the anatomy of the brain. Long-term chronic stress can cause us physiological harm and emotional difficulties. Refer to Figure 6-1. Figure 6-1 The Stress Response. (Redrawn from Brigham, D. D. [1994]. Imagery for getting well: clinical applications of behavioral medicine. New York, Norton. In Varcarolis, E. [2013]. Essentials of psychiatric mental health nursing, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Saunders.) The two stress disorders identified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) are posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and acute stress disorder (ASD). Both disorders follow exposure to an extremely traumatic event, usually outside the range of normal experience (e.g., natural disasters, crime-related events, acts of terrorism, bombings, car or train wrecks, torture/kidnap, military combat, sexual assault, witnessing a violent death or mutilation, diagnosis of a life-threatening disease). Patients not only feel fear, but a sense of hopelessness and horror. The common element in all of these experiences is the individual’s extraordinary helplessness or powerlessness in the face of such stressors. Although the prevalence of PSTD is about 7% in the general population (Black & Andreasen, 2011), the incidence of PTSD in Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans is 19% to 20% (RAND Corporation, 2008). War veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan who screened positive for PTSD were four times more likely to endorse suicidal ideation then non-PTSD veterans (Jakupcak, 2009) and have dangerous levels of alcohol use (Tull, 2010). Major depression frequently co-occurs with PTSD. Studies have found that when PTSD and major depressive disorder (MDD) go untreated or undertreated, there are many painful repercussions, such as marital problems, unemployment, heavy substance abuse, aggressive behaviors, and suicide (RAND Corporation, 2008; Glantz, 2010). Table 6-1 identifies some effective therapeutic approaches used in the treatment of PTSD, and Table 6-2 for pharmacology that might help alleviate some of the symptoms often associated with individuals with PTSD (see end of chapter). Table 6-1 Most Effective Therapeutic Approaches * Abreaction is the release of tension by recalling, talking about, or reliving traumatic events. The main difference between PTSD and ASD is one of time. ASD lasts from 2 days to 4 weeks and occurs within 4 weeks of the traumatic event. PTSD can last for years if early treatment is not sought. Assessment Findings/Diagnostic Cues: • Maintains self-control without supervision • Satisfaction with coping ability • Satisfaction with close relationships • Use of available social supports • Increased psychological comfort Patient will: • Use three new effective relaxation strategies to help reduce tension and anxiety by (date) • Talk about a traumatic event, fears, terrors, and experiences and demonstrate congruent feelings by (date) • Participate in social skills training targeting specific previously identified behaviors • Demonstrate a new sense of control over certain situations or events by (date) • Agree to continue with treatment goals and management strategies by (date) Patient will: • Identify three coping skills he or she believes would improve his or her sense of well-being and functioning and agree to work on them with (nurse/staff/clinician) within 1 week • Identify two problems that, if addressed, would improve patient’s quality of life and those of family/friends/coworkers/boss (e.g., impulse control, assertiveness, social skills) There are no medications that can “treat” PTSD; the most successful treatment is a multimodal approach (Table 6-1). There are medications available, however, that might help with some of the symptoms that accompany PTSD Refer to (Table 6-2). * Refer to Chapter 5 for these techniques. * Please refer to Chapter 5 for these techniques.

Stress and Stress-Related Disorders

OVERVIEW

Stress Disorders

Some Related Factors (Related To)

Events outside the range of usual human experience (e.g., adventitious crisis)

Events outside the range of usual human experience (e.g., adventitious crisis)

Physical and psychological abuse

Physical and psychological abuse

Witnessing violent death or mutilations

Witnessing violent death or mutilations

Motor vehicle and industrial accidents

Motor vehicle and industrial accidents

Natural disasters and man-made disasters

Natural disasters and man-made disasters

Some Defining Characteristics (As Evidenced By)

Outcome Criteria

Long-Term Goals

Short-Term Goals

INTERVENTIONS AND RATIONALES

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree