Community Assessment

Holly Cassells

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Discuss the major dimensions of a community.

2. Identify sources of information about a community’s health.

3. Describe the process of conducting a community assessment.

4. Formulate community and aggregate diagnoses.

5. Identify uses for epidemiological data at each step of the nursing process.

Key terms

aggregate

census tracts

community diagnosis

community of solution

Healthy Communities

metropolitan statistical areas

needs assessment

social system

vital statistics

windshield survey

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

The primary concern of community health nurses is to improve the health of the community. To address this concern, community health nurses use all the principles and skills of nursing and public health practice. This involves using demographic and epidemiological methods to assess the community’s health and diagnose its health needs.

Before beginning this process, the community health nurse must define the community. The nurse may wonder how he or she can provide services to such a large and nontraditional “client,” but there are smaller and more circumscribed entities that comprise a community than towns and cities. A major aspect of public health practice is the application of approaches and solutions to health problems that ensure the majority of people receive the maximum benefit. To this end, the nurse works to use time and resources efficiently.

Despite the desire to provide services to each individual in a community, the community health nurse recognizes the impracticality of this task. An alternative approach considers the community itself to be the unit of service and works collaboratively with the community using the steps of the nursing process. Therefore, the community is not only the context or place where community health nursing occurs; it is the focus of community health nursing care. The nurse partners with community members to identify community problems and develop solutions to ultimately improve the community’s health.

Another central goal of public health practitioners is primary prevention, which protects the public’s health and prevents disease development. Chapter 3 discussed how these “upstream efforts” are intended to reduce the pain, suffering, and huge expenditures that occur when significant segments of the population essentially “fall into the river” and require downstream resources to resolve their health problems. In a society greatly concerned about increasingly high health care costs, the need to prevent health problems becomes dire. In addition to reducing the occurrence of disease in individuals, community health nurses must examine the larger aggregate—its structures, environments, and shared health risks—to develop improved upstream prevention programs.

This chapter addresses the first steps in adopting a community- or population-oriented practice. A community health nurse must define a community and describe its characteristics before applying the nursing process. Then, the nurse can launch the assessment and diagnosis phase of the nursing process at the aggregate level and incorporate epidemiological approaches. Comprehensive assessment data are essential to directing effective primary prevention interventions within a community.

Gathering these data is one of the core public health functions identified in the Institute of Medicine’s (1988) original report on the future of public health. The community health nurse participates in assessing the community’s health and its ability to deal with health needs. With sound data, the nurse makes a valuable contribution to health policy development (Wold et al., 2008).

The nature of community

Many dimensions describe the nature of community. These include an aggregate of people, a location in space and time, and a social system (Box 6-1).

Aggregate of People

An aggregate is a community composed of people who share common characteristics. For example, members of a community may share residence in the same city, membership in the same religious organization, or similar demographic characteristics such as age or ethnic background. The aggregate of senior citizens, for example, comprises primarily retirees who frequently share common ages, economic pressures, life experiences, interests, and concerns. This group lived through the many societal changes of the past 50 years; therefore, they may possess similar perspectives on current issues and trends. Many elderly people share concern for the maintenance of good health, the pursuit of an active lifestyle, and the security of needed services to support a quality life. These shared interests translate into common goals and activities, which also are defining attributes of a common interest community. Communities also may consist of overlapping aggregates, in which case some community members belong to multiple aggregates.

Many human factors help delineate a community. Health-related traits, or risk factors, are one aspect of “people factors” to be considered. People who have impaired health or a shared predisposition to disease may join together in a group, or community, to learn from and support each other. Parents of disabled infants, people with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), or those at risk for a second myocardial infarction may consider themselves a community. Even when these individuals are not organized, the nurse may recognize that their unique needs constitute a form of community, or aggregate.

A community of solution may form when a common problem unites individuals. Although people may have little else in common with each other, their desire to redress problems brings them together. Such problems may include a shared hazard from environmental contamination, a shared health problem arising from a soaring rate of teenage suicide, or a shared political concern about an upcoming city council election. The community of solution often disbands after problem resolution, but it may subsequently identify other common issues.

Each of these shared features may exist among people who are geographically dispersed or in close proximity to each other. However, in many situations, proximity facilitates the recognition of commonality and the development of cohesion among members. This active sharing of features fosters a sense of community among individuals.

Location in Space and Time

Regardless of shared features, geographic or physical location may define communities of people. Traditionally, community is an entity delineated by geopolitical boundaries; this view best exemplifies the dimension of location. These boundaries demarcate the periphery of cities, counties, states, and nations. Voting precincts, school districts, water districts, and fire and police protection precincts set less visible boundary lines.

Census tracts subdivide larger communities. The U.S. Census Bureau uses them for data collection and population assessment. Census tracts facilitate the organization of resident information in specific community geographic locales. In densely populated urban areas, the size of tracts tends to be small; therefore, data for one or more census tracts frequently describe neighborhood residents. Although residents may not be aware of their census tract’s boundaries, census tract data help define and describe neighborhood communities.

A geographic community can encompass less formalized areas that lack official geopolitical boundaries. A geographic landmark may define neighborhoods (e.g., the East Lake section of town or the North Shore area). A particular building style or a common development era also may identify community neighborhoods. Similarly, a dormitory, a communal home, or a summer camp may be a community because each facility shares a close geographic proximity. Geographic location, including the urban or rural nature of a community, strongly influences the nature of the health problems a community health nurse might find there. Public health is increasingly recognizing that the interaction of humans with the natural environment and with constructed environments, consisting of buildings and spaces for example, is critical to healthy behavior and quality of life. The spatial location of health problems in a geographic area can be mapped with the use of Geographic Information System software, assisting the nurse to identify vulnerable populations and for public health departments to develop programs specific to geographic communities.

Location and the dimension of time define communities. The community’s character and health problems evolve over time. Although some communities are very stable, most tend to change with the members’ health status and demographics and the larger community’s development or decline. For example, the presence of an emerging young workforce may attract new industry, which can alter a neighborhood’s health and environment. A community’s history illustrates its ability to change and how well it addresses health problems over time.

Social System

The third major feature of a community is the relationships that community members form with each other. Community members fulfill the essential functions of community by interacting in groups. These functions provide socialization, role fulfillment, goal achievement, and member support. Therefore, a community is a complex social system, and its interacting members comprise various subsystems within the community. These subsystems are interrelated and interdependent (i.e., the subsystems affect each other and affect various internal and external stimuli). These stimuli consist of a broad range of events, values, conditions, and needs.

A health care system is an example of a complex system that consists of smaller, interrelated subsystems. A health care system can also be a subsystem because it interacts with and depends on larger systems such as the city government. Changes in the larger system can cause repercussions in many subsystems. For example, when local economic pressures cause a health department to scale back its operations, this affects many subsystems. The health department may eliminate or reduce programs, limit service to other health care providers, reduce access to groups that normally use the system, and deny needed care to families who constitute subsystems in society. Almost every subsystem in the community must react and readjust to such a financial constraint.

Healthy communities

Complex community systems receive many varied stimuli. The community’s ability to respond effectively to changing dynamics and meet the needs of its members indicates productive functioning. Examining the community’s functions and subsystems provides clues to existing and potential health problems. Examples of a community’s functions include the provision of accessible and acceptable health services, educational opportunities, and safe, crime-free environments.

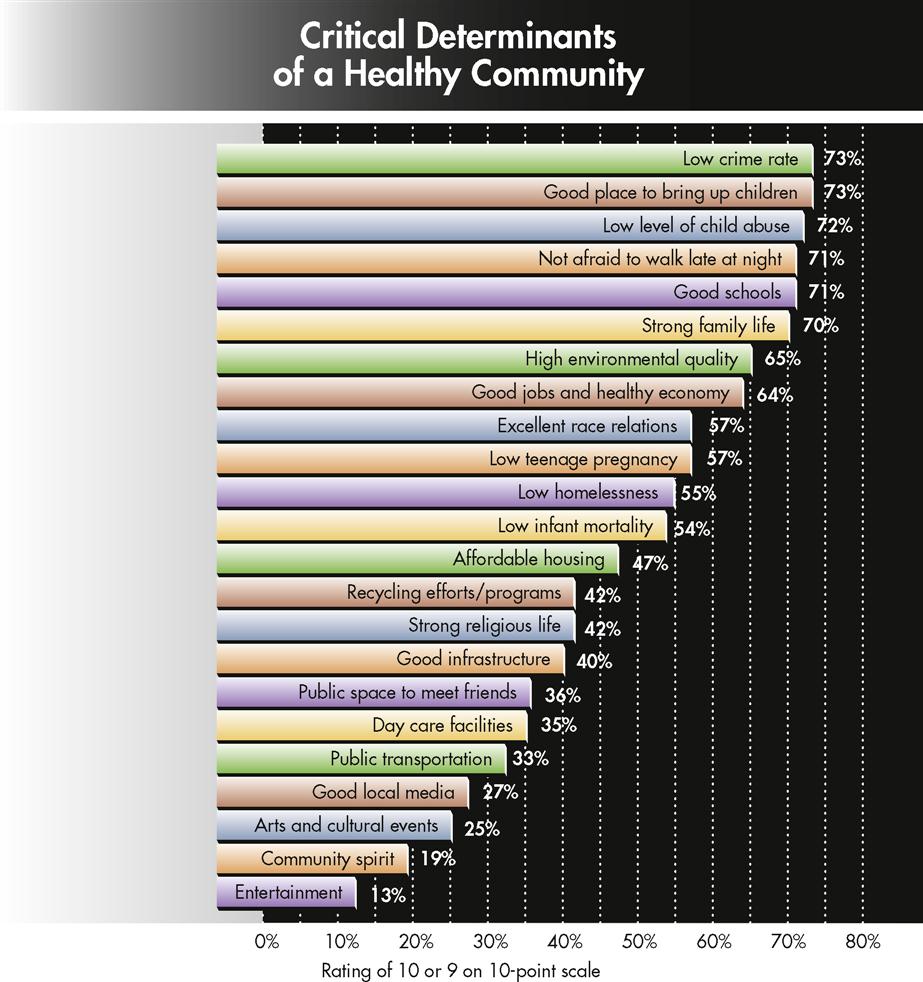

The model in Figure 6-1 suggests assessment dimensions that can help a nurse develop a more complete list of critical community functions. The community health nurse can then prioritize these functions from a particular community’s perspective. For example, a study of Americans’ views on health and healthy communities suggested that the public is more concerned with quality-of-life issues than the absence of disease. Figure 6-2 indicates that the most important determinants of a healthy community are low crime rates and a child-friendly neighborhood environment (Healthcare Forum, 1994).

The movement called Healthy Communities helps community members bring about positive health changes. Involving more than 1400 cities worldwide, the model stresses that interconnectedness among people and among public and private sectors is essential for local communities to address the causes of poor health (Healthy Communties Institute, 2009). Urban communities are encouraged to consider the health consequences of new policies and programs they introduce by conducting Health Impact Assessments (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2010). These assessments of projects such as the potential impact of transit systems and sick leave policies, serve an important function of bringing a public health perspective to urban and civic initiatives. Each community and aggregate presumably will have a unique perspective on critical health qualities. Indeed, a community or aggregate may have divergent definitions of health, differing even from that of the community health nurse (Aronson, Norton, and Kegler, 2007). Nevertheless, nurses and health professionals work with communities in developing effective solutions that are acceptable to residents. Building a community’s capacity to address future problems is often referred to as developing community competence. The nurse assesses the community’s commitment to a healthy future, the ability to foster open communication and to elicit broad participation in problem identification and resolution, the active involvement of structures such as a health department that can assist a community with health issues, and the extent to which members have successfully worked together on past problems. This information provides the nurse with an indication of the community’s strengths and potential for developing long-term solutions to identified problems.

Assessing the community: sources of data

The community health nurse becomes familiar with the community and begins to understand its nature by traveling through the area. The nurse begins to establish certain hunches or hypotheses about the community’s health, strengths, and potential health problems through this down-to-earth approach, called “shoe leather epidemiology.” The community health nurse must substantiate these initial assessments and impressions with more concrete or defined data before he or she can formulate a community diagnosis and plan.

Community health nurses often perform a community windshield survey by driving or walking through an area and making organized observations. The nurse can gain an understanding of the environmental layout, including geographic features and the location of agencies, services, businesses, and industries, and can locate possible areas of environmental concern through “sight, sense, and sound.” The windshield survey offers the nurse an opportunity to observe people and their role in the community. Box 6-2 provides examples of questions to guide a windshield survey assessment. See illustrations depicting an actual “windshield survey” on p. 95.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree