Herbal and Dietary Supplement Therapy

Objectives

Key Terms

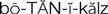

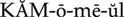

dietary supplements ( ) (p. 811)

) (p. 811)

herbal medicines ( ) (p. 813)

) (p. 813)

botanicals ( ) (p. 813)

) (p. 813)

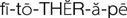

phytomedicine ( ) (p. 813)

) (p. 813)

phytotherapy ( ) (p. 813)

) (p. 813)

Herbal Medicines, Dietary Supplements, and Rational Therapy

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

Over the past two decades, there has been a tremendous resurgence in the popularity of self-care and alternative therapies, including acupuncture, aromatherapy, homeopathy, vitamin and other supplement therapy, and herbal medicine. When herbal preparations are labeled “all natural” these products become attractive to the general public because the general perception is that “all natural” is synonymous with “better” and not harmful.

There also has been a greater emphasis on health, wellness, and disease prevention, which contributes to the perception that herbal preparations are harmless. Some of the more than 250 herbal medicines and hundreds of combinations of other supplements may be beneficial, but unfortunately, the whole field of complementary medicine is fraught with false claims, lack of standardization, and adulteration and misbranding of products.

Regulatory Legislation

In the early 1990s, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) threatened to ban from the U.S. market herbal medicines and other types of supplements that were being touted as good for health until appropriate scientific studies were completed to prove that these products were safe and effective. Such an uproar was created by this threat that Congress passed the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994. Under this act, almost all herbal medicines, vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and other supplemental chemicals used for health were reclassified legally as dietary supplements, a food category. The legislation also allows manufacturers to include information on the label and through advertisements about how these products affect the human body. These labels and advertisements also must contain a statement that the product has not yet been evaluated by the FDA for treating, curing, or preventing any disease. The law does not prevent other people (e.g., nutritionists, health food store clerks, herbalists, strength coaches, or other unlicensed individuals) from making claims (founded or unfounded) about the therapeutic effects of supplement ingredients.

The result of the new law is that dietary supplements are not required to be safe and effective, and unfounded claims of therapeutic benefit abound. Hundreds of herbal medicines and other dietary supplements are marketed in the United States as single- and multiple-ingredient products for an extremely wide variety of uses, all implying that they will improve one’s health.

Independent Product Testing

The vast majority of the popular claims made for herbal medicines and dietary supplements are unproven. The FDA issued good manufacturing practices which became mandatory for the dietary supplement industry as of June 2010 (www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/Manufacturing/ucm090016.htm).

Since 1999, ConsumerLab.com has been testing dietary supplements, and the U.S. Pharmacopeia launched the Dietary Supplement Verification Program in 2001 and began testing products that year. USP is a scientific nonprofit organization that establishes federally recognized standards for the quality of drugs and dietary supplements. It is the only such organization that also offers voluntary verification services to help ensure dietary supplement quality, purity, and potency. USP is the only non-profit standards-setting organization recognized in U.S. federal law that also offers verification services. USP standards for prescription drugs and OTC medicines are FDA-enforceable per the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. In 2003, the National Sanitation Foundation International began testing dietary supplements. Products that pass testing are eligible to bear the mark of approval from the testing agency (Figure 48-1).

It is important to remember that the products are tested for labeled potency, good manufacturing practices, and lack of contamination, but they are not tested for safety and efficacy or for manufacturer’s claims on the label. Dietary supplement therapy, under current legal standards, creates an ethical dilemma for nurses and other health care professionals. Licensed health care professionals have a moral and ethical responsibility to recommend only medicines that are proven to be safe and effective. They should be aware of a medicine’s legal use versus its popular use, its potential for toxicity, and its potential for interactions with other medicines. Box 48-1 lists the factors to consider when discussing dietary supplements.

Studies have shown that 40% to 78% of patients fail to disclose the use of complementary and herbal therapy to their health care provider, resulting in a lack of guidance for these products (Chong, 2006).

It is important for the nurse to inquire about the use of these products when obtaining a history from the patient. The nurse can direct the patient and family toward reliable web resources, such as the National Institutes of Health website, which provide sound scientific data on supplements.

Nursing Implications for Herbal and Diet Supplement Therapy

Nursing Implications for Herbal and Diet Supplement Therapy

Assessment

• Discuss specific dietary supplement products and the patient’s reasons for using these products.

• What cultural or ethnic beliefs does the individual espouse?

History of Symptoms.

Examine data to determine the individual’s understanding of the symptoms or the disease process for which the individual began taking supplements.

Medication History

Cultural and Ethnic Beliefs.

If cultural issues are involved in the use of the supplement products, research the belief system and ways that the nurse can appropriately be involved in supporting the individual.

Implementation

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Expectations of Therapy.

Discuss the expectations of therapy with the patient and why self-treatment needs to be discussed with other members of the health care team. Emphasize to the patient that supplement products can and do interact with other medications.

Fostering Health Maintenance

Written Record.

Enlist the patient’s aid in developing and maintaining a written record of monitoring parameters (e.g., blood pressure, pulse, daily weight, degree of pain relief). (See the Patient Self-Assessment Form: Self-Monitoring Drug Therapy Record in Appendix H on the ![]() Evolve Web site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton). Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form and instruct the patient to take the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions prescribed. The health care team members must understand that simply telling the patient not to take supplements may result in the patient’s hiding the use of these products, creating additional problems.

Evolve Web site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton). Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form and instruct the patient to take the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions prescribed. The health care team members must understand that simply telling the patient not to take supplements may result in the patient’s hiding the use of these products, creating additional problems.

Herbal Therapy

Herbal medicine is perhaps as old as the human race. For thousands of years, civilizations have depended on substances found in nature to treat illnesses. Herbal medicines are defined as natural substances of botanical or plant origin. Other names for herbal medicines are botanicals, phytomedicine, and phytotherapy.

Actions

Two products derived from aloe plant leaves are aloe gel and aloe latex. Aloe gel (commonly known as aloe vera) is a gelatinous extract from the sticky cells lining the inner portion of the leaf. Aloe gel is composed of polysaccharides and lignin, salicylic acid, saponin, sterols, triterpenoids, and a variety of enzymes. Aloe gel may possibly inhibit bradykinin and histamine, reducing pain and itching. Aloe latex (resin), also known as an aloin, contains pharmacologically active anthraquinone derivatives that, when taken orally, act as a laxative by irritating the intestinal lining, increasing peristalsis and fluid and electrolyte secretions.

Uses

Aloe has been used as a medicinal agent for more than 5000 years for a vast array of internal and external illnesses, including arthritis, colitis, the common cold, ulcers, hemorrhoids, seizures, and glaucoma. Aloe gel is the form most commonly used in the cosmetic and health food industries. Most recently, aloe gel has been marketed for topical use to treat pain, inflammation, and itching and as a healing agent for sunburn, skin ulcers, psoriasis, and frostbite. The FDA has reviewed clinical studies of aloe gel and has not found adequate scientific evidence to support these claims. Therefore, aloe gel is not classified as a drug but is allowed to remain on the market as a cosmetic for topical use. It is frequently used as a co-ingredient in skin care products; however, the product labeling should not make therapeutic claims of the aloe gel because none has been substantiated through scientific studies.

Aloe latex contains anthraquinone derivatives that, when taken orally, act as a laxative. There is a concern, however, about carcinogenicity, so aloe latex has been removed from the pharmaceutical market because it is not proven to be safe and effective. Historically, aloe has been known as a fragrant wood used as incense, unrelated to aloe vera.

Nursing Implications for Aloe

Nursing Implications for Aloe

Availability

Aloe gel: Moisturizing lotion, shampoo, hair conditioner, gels, toothpaste, aloe juice for topical application. Capsules and tinctures are also available for oral use. There are no proven therapeutic effects from these products.

Aloe latex: Aloe juice drinks for catharsis; whole leaf aloe vera: juice.

Monitoring

Adverse Effects.

When applied to the skin, no adverse effects have been reported. When taken orally, aloe products may cause diarrhea due to anthraquinone content.

Drug Interactions

Diabetic Therapy.

Monitor blood glucose levels closely because of claims that when taken orally, aloe may have hypoglycemic effects.

Actions

The active ingredients in black cohosh are complex triterpenes and flavonoids. It is thought that these agents have estrogen-like effects by suppressing release of luteinizing hormone and by binding to estrogen receptors in peripheral tissue.

Uses

Black cohosh is used to reduce symptoms of premenstrual syndrome, dysmenorrhea, and menopause. Therapy is not recommended for longer than 6 months. Black cohosh should not be used in the first two trimesters of pregnancy because of its uterine-relaxing effects.

Nursing Implications for Black Cohosh

Nursing Implications for Black Cohosh

Availability

PO: Elixirs, tablets, capsules.

Monitoring

Adverse Effect.

Upset stomach is rare.

Comments

Do not confuse black cohosh with blue cohosh. Blue cohosh is used as an antispasmodic and uterine stimulant to promote menstruation or labor, but it is different and potentially more toxic than black cohosh. Beware of commercial products that contain both black and blue cohosh when only black cohosh is sought.

Actions

Two herbs are known as chamomile: German chamomile and Roman chamomile. The therapeutic effects of chamomile derive from a complex mixture of different compounds. The anti-inflammatory and antispasmodic effects come from a volatile oil containing matricin, bisabolol, bisabolol oxides A and B, and flavonoids such as apigenin and luteolin. Coumarins, herniarin, and umbelliferone exhibit antispasmodic properties. Chamazulene has also been shown to possess anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties.

Uses

Both chamomiles are used in herbalism and medicine; however, German chamomile is the species most commonly used in the United States and Europe, whereas Roman chamomile is favored in Great Britain. Chamomile is used as a digestive aid for bloating, an antispasmodic and anti-inflammatory in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, an antispasmodic for menstrual cramps, an anti-inflammatory for skin irritation, and a mouthwash for minor mouth irritation or gum infections. Plant extracts are used in cosmetic and hygiene products in the form of ointments, lotions, and vapor baths for topical application. For internal use, chamomile is taken in the form of a strong tea.

Nursing Implications for Chamomile

Nursing Implications for Chamomile

Availability

German chamomile is available as ointment and gel in strengths of 3% to 10%. As a bath additive, 50 g is added to 1 L of water. For internal use as a tea, pour 150 mL of boiling water over 3 g of chamomile (1 teaspoon = 1 g of chamomile), cover for 5 to 10 minutes, and then strain.

Monitoring

Adverse Effects.

Rare hypersensitivity reactions may occur in patients who are allergic to ragweed, asters, chrysanthemums, or daisies.

Drug Interactions

No clinically significant drug interactions have been reported with chamomile.

Actions

Echinacea is a nonspecific stimulator of the innate (nonspecific) immune system. It stimulates phagocytosis and effector cell activity. There is an increased release of tumor necrosis factors and interferons from macrophages and T lymphocytes, which increases the body’s resistance to bacterial and viral infection. It may have anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting hyaluronidase, a potent inflammatory agent. Echinacea has no direct bactericidal or bacteriostatic effects.

Uses

As a nonspecific immunostimulant, echinacea may prevent or treat viral respiratory tract infections such as the common cold or flu. Well-designed clinical studies have shown equivocal results. Symptoms of the common cold may be reduced if echinacea is taken during the early, acute phase. Echinacea has also been used to treat urinary tract infections and may be applied externally to difficult-to-heal superficial wounds. Because of its immunomodulating effects, it is recommended that it not be used for more than 8 weeks at a time.

Nursing Implications for Echinacea

Nursing Implications for Echinacea

Availability

PO: Echinacea is available as dried roots, teas, tinctures, and dry powder extracts.

Monitoring

Adverse Effects.

Rare hypersensitivity reactions may occur in patients who are allergic to ragweed, asters, chrysanthemums, or daisies.

Comments

Because echinacea appears to be an immunomodulator, it is not recommended for patients with autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis or lupus erythematosus, or diseases affecting the immune system, such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Action

The active ingredient in ephedra is the alkaloid ephedrine.

Uses

Ephedra was perhaps the first Chinese herbal medicine to be used in Western medicine. It is used as a bronchodilator for asthma, as a nasal decongestant, and as a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant. It is contraindicated in patients with heart conditions, hypertension, diabetes, and thyroid disease.

Nursing Implications for Ephedra

Nursing Implications for Ephedra

Monitoring

Adverse Effects.

Ephedra elevates systolic and diastolic blood pressures and heart rate, causing palpitations. It also causes nervousness, headache, insomnia, and dizziness.

Comments

Actions

There is significant controversy as to which ingredients in feverfew are therapeutic. Several sesquiterpene lactones are smooth muscle relaxants in the walls of the cerebral blood vessels and may be the source of antimigraine activity. Feverfew has also been shown to inhibit the release of arachidonic acid, which serves as a substrate for production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes. Feverfew also inhibits release of serotonin and histamine from platelets and white cells, which helps prevent or control migraine headaches. Parthenolide, long thought to be the primary active ingredient, has been shown by one well-controlled study to be of minimal therapeutic effect. Perhaps additional compounds work synergistically with parthenolide to prevent migraine headaches.

Uses

Feverfew is used to reduce the frequency and severity of migraine headaches. Its anti-inflammatory effects have also been used to treat rheumatoid arthritis.

Nursing Implications for Feverfew

Nursing Implications for Feverfew

Availability

PO: Leaf powder for making tea; tablets.

Monitoring

Adverse Effects.

Fresh feverfew leaves appear to be most effective in reducing the frequency and pain associated with migraine headaches. Ulcerations of the oral mucosa and swelling of the lips and tongue have been reported by 7% to 12% of patients. Feverfew therapy should be discontinued if these lesions develop. Rare hypersensitivity reactions may occur in patients who are allergic to ragweed, asters, chrysanthemums, or daisies.

Comments

The sesquiterpene lactone content is higher in the flowering tops than in the leaves, stalks, and roots. The sesquiterpene lactone content diminishes with time and with exposure to light. Because the active ingredients are not known, there are no standards established for purity. Many products sold in the United States have been found to have low, variable quantities of sesquiterpene lactones.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

)

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

)