Care of Patients with Cognitive Disorders

Objectives

1. Discuss the incidence and significance of cognitive disorders in the elderly population.

4. Choose appropriate nursing interventions for the care of patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

5. Identify the assessment skills that are necessary to accurately monitor a cognitive disorder.

1. Devise a care plan with at least six interventions for a patient who is confused and disoriented.

Key Terms

Alzheimer’s disease (ĂWLTZ-hī-mĕrz dĭ-ZĒZ, p. 1085)

biomarker (p. 1088)

cognition (kŏg-NĬ-shŭn, p. 1085)

confabulation (kŏn-fă-bū-LĀ-shŭn, p. 1086)

delirium (dĕ-LĬR-ē-ŭm, p. 1085)

delusion (dĕ-LŪ-shŭn, p. 1086)

dementia (dē-MĔN-shē-ă, p. 1085)

global amnesia (GLŌ-băl ăm-NĒ-zhē-ă, p. 1097)

hallucinations (hă-lū-sĭ-NĀ-shŭnz, p. 1086)

illusions (ĭ-LŪ-shŭnz, p. 1086)

sundowning (SŬN-doun-ĭng, p. 1094)

vascular dementia (VĂS-kū-lăr dē-MĔN-shē-ă, p. 1085)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Overview of cognitive disorders

Cognition refers to mental processes of perception, memory, judgment, and reasoning. It includes the ability to perceive and process information. A cognitive disorder is diagnosed when there is a significant change in cognition from a previous level of functioning. Cognitive disorders greatly affect the quality of life for affected individuals, families, and friends. Although cognitive disorders do occur across the life span, they are often linked to the neurobiologic changes that accompany aging. Cognitive disorders have become increasingly common with the aging of the population. Disorders of cognition include delirium and dementia.

Delirium (acute confusion) is characterized by a change in overall cognition and level of consciousness over a short time. Dementia, on the other hand, is characterized by several cognitive deficits, memory in particular, and tends to be more chronic. Both conditions are classified according to etiology (cause or origin of disease). Examples of etiologies for delirium are ingestion of a toxic substance or a serious infection. An example of etiology for dementia is multiple small blood clots that cause brain tissue damage (known as vascular dementia). Alzheimer’s disease (a degenerative disease of the brain) is another example of dementia, although the exact cause is unknown. The difference between the two conditions is that delirium is an acute condition that requires immediate treatment and dementia is a chronic condition. Reversing the symptoms of delirium depends on timely diagnosis and treatment. It also is important to note that delirium can coexist with dementia. If delirium is recognized and promptly treated, the patient with preexisting dementia should be restored to a previous level of functioning.

Delirium

Many conditions or physiologic alterations can cause delirium. Some examples are cerebrovascular accident; drug overdose, toxicity, or withdrawal; tumors; systemic infections; fluid and electrolyte imbalances; and malnutrition. The onset of acute delirium is sudden. The patient may be alert or lethargic, depending on the cause of the delirium, or may appear very confused. The attention span changes and overall awareness of the environment is decreased. Orientation is impaired, as are recent and immediate memory. Speech may be incoherent, and overall thinking can be disorganized and distorted. The patient will not be able to communicate her thoughts to you in a meaningful way. In delirium, a patient may experience illusions (misinterpretations of reality). For example, a pen appears to be a knife, or a shadow on the floor appears to be a menacing monster. If your patient appears to be talking to someone who is not there, it is likely that she is experiencing hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that are not there). If she insists that you are an angel of death and destruction, this is an example of a delusion (belief in a false idea).

Problem-solving ability and judgment may be diminished, but not completely absent. Consequently, the patient may not make good decisions, or may become combative or hostile if the nurse or family member attempts to intervene. The general features of delirium are the same for all the causes, and nursing care is basically the same; the main difference is in diagnosis and treatment of the underlying cause.

Substance-Induced Delirium

Substance-induced delirium can be caused by withdrawal from a substance, intoxication with a substance, or side effects from a medication (see Chapter 47). Many classes of medications can produce symptoms of delirium. Some common examples are anesthetics, analgesics, sedative-hypnotics, any products with anticholinergic activity (tricyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, theophylline derivatives, and antipsychotics), and histamine (H2)-receptor blockers (e.g., famotidine, cimetidine, and ranitidine). Commonly prescribed beta blockers and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can also cause symptoms of delirium.

Diagnosis and treatment depend on taking a thorough history. If the patient is unable to give you a history, elicit help from the family. It is not unusual for a person to be taking large amounts of over-the-counter medications and forget to mention them because the medications were not prescribed by a physician. Pay attention to drug interactions and incompatibilities, and consult with the pharmacist as needed. Early recognition can facilitate a faster recovery. If the medication accumulates over several days, elimination of the substance from the body takes much longer and places the patient in even greater danger.

Dementia

There are several different types of dementia, and these conditions are also classified according to the underlying cause. Examples include Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal lobe dementia, Huntington’s disease, Korsakoff’s syndrome, vascular dementia, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) dementia complex, and Parkinson’s disease. The onset for dementia is slow, and the condition may progress over months to years. The patient is generally alert. Orientation to person, place, and time and recent memory may be impaired. In later stages of dementia, patients lose remote memory as well. You would observe that the patient has difficulty with abstracting thoughts and a poverty of thoughts. Confabulation (making up experiences to fill conversational gaps) and impaired judgment are common. Often, there is a noticeable change in personality. Hallucinations, delusions, and illusions usually are not present. These patients experience fragmented sleep rather than a reversed cycle.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common degenerative disease of the brain. Approximately 5.4 million Americans have AD (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011), and there is no known cause or cure. AD typically affects people over 65 years of age, but can also strike younger people. The 85+ age-group is currently the fastest growing age group in the United States. It is estimated that 50% of this age group have AD.

In AD, there is a loss of neurons in the frontal and temporal lobes. The atrophy in these areas accounts for the patient’s inability to process and integrate new information and to retrieve memories. Brain biopsies of AD patients have revealed nerve cells that are tangled and twisted and an abnormal buildup of proteins. Production of neurotransmitters (e.g., acetylcholine, serotonin) is relatively decreased for these patients (see Chapter 49). Risk factors for developing Alzheimer’s include lack of exercise, lower educational level, depression, chronic kidney disease, obesity in midlife, disadvantaged childhood environment, exposure to metals or toxins, and a previous head injury (Bassil & Grossberg, 2009a).

Signs and Symptoms

AD has a slow onset and variable rate of progression. Eventually, it is fatal. According to the Alzheimer’s Association (2011), behavioral patterns and symptoms are divided into seven stages: (1) no impairment, (2) very mild cognitive decline, (3) mild cognitive decline, (4) moderate cognitive decline, (5) moderately severe cognitive decline, (6) severe cognitive decline, and (7) very severe cognitive decline. During the first two stages, there will be no symptoms or there will be changes that appear to be due to normal aging. The early signs and symptoms of beginning mental deterioration include forgetfulness, recent memory loss, difficulty learning and remembering, inability to concentrate, and a decline in personal hygiene, appearance, and inhibitions. Later the patient becomes quite confused and unable to make judgments, has difficulty communicating, suffers losses in motor function, and becomes dependent on others. Behavioral manifestations can also be categorized in three stages, mild, moderate and severe (Rohl, 2006 & Hussey, 2011) (Box 48-1).

Patients have a progressive loss of common cognitive functions. You observe that the patient has trouble remembering words (anomia) or verbally expressing himself (aphasia), and he is unable to write down his thoughts (agraphia) or understand written language (alexia). If he holds a common object such as a spoon, he does not seem to recognize it (agnosia), and he cannot put on his shirt, although he has the strength and motor movement to dress himself (apraxia: inability to perform an activity despite motor function). He has difficulty planning ahead and he attends fewer social functions. He also displays some problems with balance and gait. For example, an 85-year-old retired attorney displays the criteria for dementia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR).

Diagnosis

In 2011, new criteria and guidelines for the diagnosis of AD were presented as the result of an international collaboration to review the original 1984 criteria and incorporate research findings to improve the diagnostic process. The new guidelines propose three stages: (1) preclinical AD, (2) very mild cognitive impairment (MCI) caused by AD, and (3) dementia caused by AD.

Currently there are no criteria for physicians to use in making the diagnosis of preclinical AD. Future research on preclinical AD is based on the assumption that there are biologic processes that are occurring before the onset of actual symptoms. The proposed research goals for the preclinical stage are to identify biomarkers that will confirm a diagnosis of AD. (A biomarker is an objective measure that indicates the presence of disease.)

In making the diagnosis, the physician uses a detailed medical and family history and conducts a thorough physical, neurologic, and functional assessment. The benefits of early diagnosis include being able to include the patient in the planning, to proactively ensure safety, to reduce the family’s blaming the patient for behaviors that are part of the disease process, and to counter patient and family denial (Bennett, 2009). Your patient may undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to rule out pathologic lesions. The diagnostic use of positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) are controversial, but are being considered. Apolipoprotein E4 genotyping is used to confirm the diagnosis of late-onset AD. Research for new diagnostic tests for AD will continue. Three new clinical criteria may be predictors for early AD: amyloid protein in the spinal fluid, plus a biomarker with slight cognitive changes, or brain atrophy on imaging (Sullivan, 2010). The DSM-IV-TR provides behavioral criteria for AD.

Treatment

Current medications do not cure AD, but may improve intellectual functioning and slow the progression of the disease (McGuinness et al.,  2009) The evidence indicates that the benefit of these drugs is modest (Qaseem et al.,

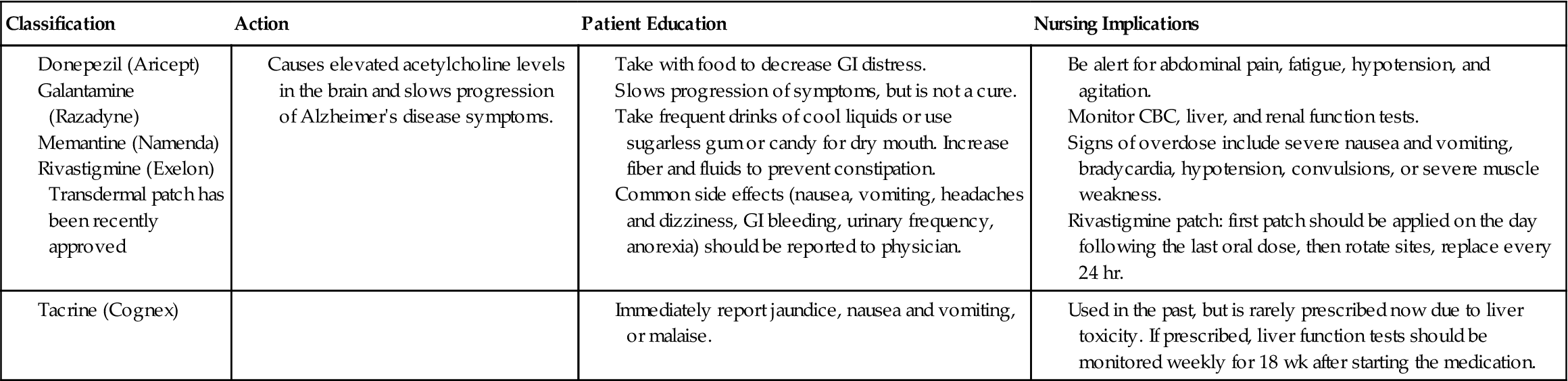

2009) The evidence indicates that the benefit of these drugs is modest (Qaseem et al.,  2008). Research is being done on immunotherapies that target the protein that contributes to the formation of the neurofiber tangles (Alzheimer’s Association International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease, 2010). Table 48-1 describes medications used to treat cognitive disorders and their nursing implications. Behavioral interventions such as the three Rs (repeat, reassure, redirect) or the ABCs (antecedents, behaviors, consequences) can be adapted to match the patient’s current level of function (Kalapatapu & Neugroschi, 2009). In a recent study (Ancoli-Israel, et al., 2008), patients with AD and obstructive sleep apnea showed improvement in cognition after 6 weeks of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy.

2008). Research is being done on immunotherapies that target the protein that contributes to the formation of the neurofiber tangles (Alzheimer’s Association International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease, 2010). Table 48-1 describes medications used to treat cognitive disorders and their nursing implications. Behavioral interventions such as the three Rs (repeat, reassure, redirect) or the ABCs (antecedents, behaviors, consequences) can be adapted to match the patient’s current level of function (Kalapatapu & Neugroschi, 2009). In a recent study (Ancoli-Israel, et al., 2008), patients with AD and obstructive sleep apnea showed improvement in cognition after 6 weeks of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy.

Table 48-1

Table 48-1

Drugs Used to Treat Cognitive Disorders

| Classification | Action | Patient Education | Nursing Implications |

Nursing management

Assessment (Data Collection)

You may be the first health care professional who encounters a patient who is in the early stages of AD. Know and be vigilant for the 10 warning signs of AD (Alzheimer’s Association, 2010) (Box 48-2). For example, the family may tell you, “We think Dad is having problems with his memory and in completing daily tasks, and we also think he is attempting to hide his forgetfulness because he keeps misplacing things and can’t seem to solve ordinary problems. He insists on driving, but we are beginning to question his judgment. He often acts like he is searching for the right word. We can’t seem to teach him how to position a can to use a can opener. He is even confused about times when we have recently visited him, and he is moody and withdrawn during our regular visits. ” Ask the patient and the family questions about memory, ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), and any subtle changes in personality. Give specific common examples (e.g., “Does he forget to turn off the stove or to lock the doors?”). Refer this type of patient to the RN or physician because he needs an in-depth assessment and an extensive physical examination. Assessment should include the necessary data to plan measures to protect the patient.

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

Nursing diagnoses are identified to maximize safety and to minimize complications due to loss of cognitive function. For example, Risk for injury, Wandering, Confusion, Self-care deficits, and Caregiver role strain are some of the diagnoses that are used for patients with AD. Planning care for a patient with AD is based on the stage of the disease, and the family should be encouraged from the beginning to participate in developing the long-term goals (Nursing Care Plan 48-1). As the disease progresses, the patient will sustain losses in every area of function.

(Qaseem et al., 2008).

(Qaseem et al., 2008).

, 2009a).

, 2009a).

2009b).

2009b).

Nursing Care Plan 48-1

Nursing Care Plan 48-1