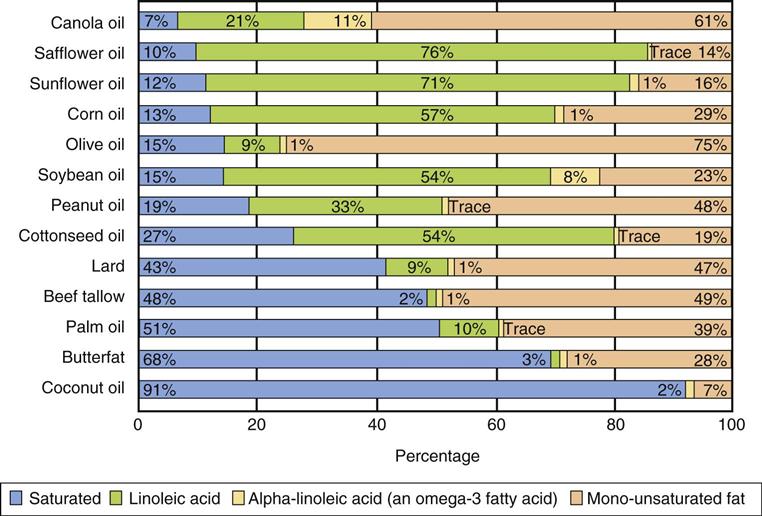

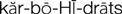

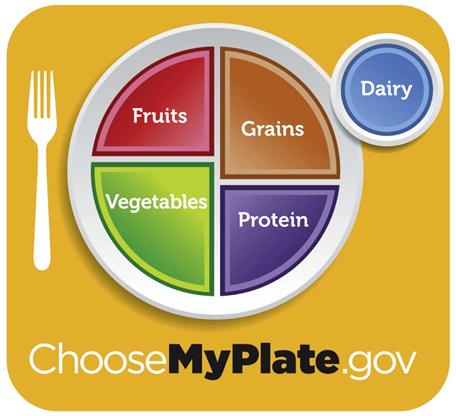

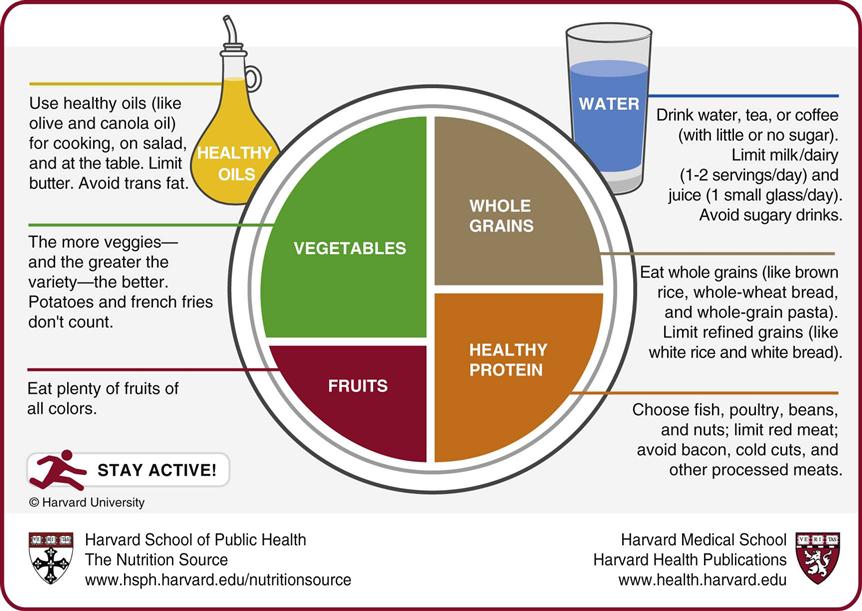

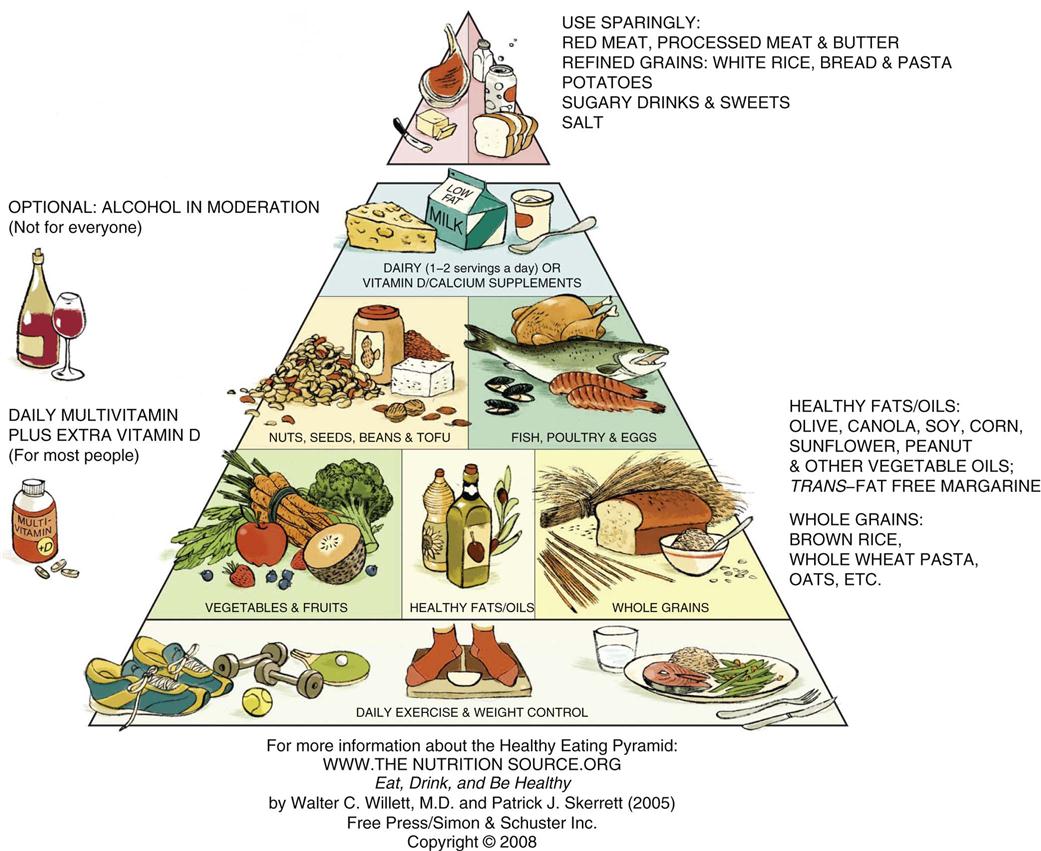

1 Identify the function of macronutrients in the body. 3 Differentiate between fat-soluble and water-soluble vitamins. 4 Discuss the functions of minerals in the body. macronutrients ( Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) ( Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) ( Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) ( Adequate Intake (AI) ( Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) ( kilocalories ( Estimated Energy Requirement (EER) ( carbohydrates ( monosaccharides ( disaccharides ( polysaccharides ( fiber ( lipids ( essential fatty acids ( gluconeogenesis ( vitamins ( minerals ( physical exercise ( marasmus ( kwashiorkor ( mixed kwashiorkor-marasmus (p. 800) enteral nutrition ( tube feedings (p. 800) parenteral nutrition ( total parenteral nutrition (TPN) ( peripheral parenteral nutrition (PPN) ( central parenteral nutrition (CPN) ( It is no coincidence that eating is one of life’s greatest pleasures. The body needs a regular source of energy to sustain its various functions, including respiration, nerve transmission, circulation, physical work, and maintenance of core temperature. There are many environmental, cultural, and behavioral reasons for what and how people eat, but the most basic is to sustain life. Because the body cannot make most of the needed nutrients, these chemicals must be supplied from external sources. For the most part, they are supplied from the food people eat. Other chemicals are supplied by air, such as oxygen, by water, and by sunlight, which helps the body manufacture vitamin D. The energy derived from external sources is converted to chemical energy by the body, which sustains the body’s functions. The heat produced during these chemical reactions maintains body temperature. Energy sources required for balanced metabolism are the macronutrients—fats, carbohydrates, fiber, and proteins—which are measured in calories (see Macronutrients, pp. 795-796). Other essential nutrients include vitamins, minerals, and water. Imbalances between energy intake (food) and energy expenditure result in gain or loss of body composition, primarily in the form of fat, which determines changes in weight. Nutritional requirements vary based on level of activity, age of the individual (e.g., infant, preschool child, adolescent, adult, and older adult), and gender. For example, there are differences in nutritional requirements for a pregnant teenager, an adult woman, and a lactating mother. The presence of disease, wound healing, and the degree of catabolism also can influence nutritional needs. Therefore, the reader should consult a reliable nutritional textbook for current detailed information. No one food source can meet all of the body’s basic nutritional requirements. Foods from a variety of groups are required to provide an optimal nutrient balance and to minimize naturally occurring toxic substances from a single food source. Two federal agencies, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, collaborate to publish Dietary Guidelines for Americans every 5 years. The latest edition is Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, released January 2011. These guidelines are based on research of nutrients in foods and recommend how to make the best food choices to promote good health. There is controversy, however, about the use of the latest scientific evidence and of the selection of committee members who make the final recommendations. There is intense lobbying by the agriculture industry and other special interest groups for committee appointments. The overarching concepts in the 2010 guidelines are (1) maintaining caloric balance over time to achieve and sustain a healthy weight and (2) consuming nutrient-dense foods and beverages (Figure 47-1 and Box 47-1). The new guidelines also encourage a healthy eating pattern described in the USDA Food Patterns (with vegetarian adaptations) and the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) Eating Plan. Also, MyPlate (Figure 47-2) now replaces MyPyramid, which supported the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005. The USDA’s website www.choosemyplate.gov contains a wealth of information on how citizens can become more calorie conscious and plan nutrient rich meals. With obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus reaching epidemic proportions over the past decade in the United States and recent research findings raising concerns, the Dietary Guidelines have undergone substantial scrutiny. The current version has been revised and updated extensively to address issues and trends related to nutrition and overall health. In retrospect, the 2005 guidelines overemphasized the intake of carbohydrates such as bread, pasta, cereal, potatoes, and rice, and did not address the issue that the American public is consuming too many refined carbohydrates (i.e., those grains that have been milled [leaving “white flour”] to eliminate the outer bran shell, which contains vitamins, minerals, and fiber). The 2010 guidelines encourage the intake of whole grains and suggest that people limit sugar intake. Another concern in the average American diet is the consumption of trans fatty acids (also called hydrogenated fats) and saturated fats, which have no known nutritional benefit but increase cholesterol levels and the frequency of heart disease. The guidelines now emphasize that intake of trans fats should be as low as possible. As of January 2006, food labels are required to list trans fat content to help consumers become aware of and reduce their intake. The primary sources of trans fats are commercially fried foods, stick margarine, processed and ready-to-eat foods, and snack foods. Research indicates that monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats have some health benefits, so the guidelines also recommend obtaining between 20% and 35% of daily calories from these types of fats. Saturated fats should continue to be limited. Primary sources of saturated fats are red meats, butter, and high-fat dairy products (e.g., whole milk) (Box 47-2 and see Figure 47-2). The guidelines recommend drinking three glasses of low-fat milk or eating three servings of other low- or non-fat dairy products each day to prevent osteoporosis, but research has not demonstrated that this is effective. Consumption of dairy products adds approximately 300 calories daily to the diet, and calcium supplements have been shown to reduce the incidence of osteoporosis without adding calories. Nutrition experts at the Harvard University School of Public Health have proposed the Healthy Eating Plate (Figure 47-3), which they claim “offers more specific and more accurate recommendations for following a healthy diet than MyPlate … and is based on the most up-to-date nutrition research … not influenced by the food industry or agriculture policy” (The Nutrition Source, 2012), and The Healthy Eating Pyramid (Figure 47-4). Some highlights of these two resources are as follows: • Daily activity and weight control serve as the foundation for the pyramid. • Whole-grain foods, fruits, and vegetables (sources of fiber, vitamins, and minerals) are emphasized. • A daily multivitamin is recommended for most people. • Moderate daily alcohol may be a healthy option unless contraindicated for specific people. A good balance for men is one or two drinks daily. Women should limit alcohol consumption to no more than one drink per day. See http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/quickstats/general_info.htm. Knowing daily calorie needs may be useful for determining whether the number consumed is appropriate in relation to the number needed each day. The best way to assess the appropriate number of calories is to monitor body weight and adjust calorie intake and participation in physical activity based on changes in weight over time. A calorie reduction of 500 calories or more per day is a common initial goal for weight loss for adults. However, maintaining a smaller deficit can have a meaningful influence on body weight over time. The effect of a calorie reduction on weight does not depend on how the reduction is produced—by reducing calorie intake, increasing caloric expenditure (more exercise), or both—yet, in research studies, a greater proportion of the calorie reduction is often due to decreasing calorie intake with a relatively smaller fraction due to increased physical activity. The National Academy of Sciences collects data and publishes a series of tables known as Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs), which provide quantitative estimates of nutrient intakes for planning and assessing diets for healthy people. The DRIs replace the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) last updated in 1989. The DRIs are actually a set of four reference values: Estimated Average Requirement, Recommended Dietary Allowances, Adequate Intake, and Tolerable Upper Intake Level. Links to the Dietary Reference Intakes updated in September, 2011, may be retrieved at www.iom.edu/Activities/Nutrition/SummaryDRIs/DRI-Tables.aspx. The Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) is a nutrient intake value that is estimated to meet the requirement of half of the healthy individuals in a group. The most widely known component of the DRIs is the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) table. It lists the average daily dietary intake level that is sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of almost all (97% to 98%) healthy individuals in a group. (Groups are based on gender, age and, if applicable, pregnancy or lactation.) Recommended dietary allowances are goals in meeting nutritional needs. RDAs do not meet the nutritional needs of ill patients and do not account for nutritional value that may be lost in cooking. The RDA is based on the EAR plus twice the standard deviation: the RDA for a nutrient is a value to be used as a goal for dietary intake by healthy individuals. There is no established benefit for healthy persons if they consume nutrient intakes greater than the RDA or Adequate Intake. Adequate Intake (AI) is a value based on observed or experimentally determined approximations of nutrient intake by a group of healthy people. The AI is used when the RDA cannot be determined. Another category in the DRI tables is the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL). This level is defined as the highest level of daily nutrient intake that is likely to pose no risk of adverse health effects to almost all those in the general population. As intake increases above the UL, the risk of adverse effects increases. The UL is not intended to be a recommended level of intake. For many nutrients, there are insufficient data on which to develop a UL. This does not mean that there is no potential for adverse effects resulting from high intake. Over time, these data will help establish the value of megadoses of vitamins and nutrients and provide information about whether there are therapeutic and toxic effects to ingestion of large doses of these chemicals. The metabolism of the macronutrients, carbohydrates, fiber, fats, and proteins provides energy for the body to maintain life (respiration, circulation, physical work, nerve transmission, core body temperature) and to repair damage induced by illness or injury. Energy is measured in kilocalories (kcal). The heat generated during these processes is reflected as body temperature. Energy balance in an individual depends on dietary energy intake and energy expenditure. An excess of energy (food) intake over that which is burned results in weight gain. Body weight is lost through burning more kilocalories than are consumed. A pound of body weight is approximately 3500 kcal. The Estimated Energy Requirement (EER) is defined as the average dietary energy intake that is predicted to maintain energy balance in a healthy adult of a defined age, gender, weight, height, and level of physical activity consistent with good health (Table 47-1). Table 47-1 Calculation of Estimated Energy Requirements (EERs)* Women ages 19 years and older: EER = 354 − (6.91 × age [yr]) + PA × (9.36 × weight [kg] + 726 × height [m]) *Men ages 19 years and older: EER = 662 − (9.53 × age [yr]) + PA × (15.91 × weight [kg] + 539.6 × height [m]) Data from Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board: Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids, Washington DC, 2005, National Academies Press, p. 185. Available at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=10490. The National Academy of Sciences published the Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein and Amino Acids in 2005. This report on macronutrients was sponsored for both the United States and Canada by several governmental agencies, including Health Canada, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USDA, and private sources. These guidelines are based on research of nutrients in foods and how the body uses energy from foods. The report recommends that to meet the body’s energy and nutritional needs while minimizing risk for chronic disease, adults should obtain 45% to 65% of their calories from carbohydrates, 20% to 35% from fat, and 10% to 35% from protein. (See Chapter 36 for the American Diabetes Association recommendations for intake of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins for a patient with diabetes mellitus.) Carbohydrates, often referred to as “sugars” because many of them taste sweet, are the major source of energy for body activities and metabolism. They occur in nature as simple and complex molecules and are water-soluble. The simple carbohydrates are also known as monosaccharides and disaccharides. Monosaccharides such as glucose (also known as dextrose), fructose, and galactose are the only sugars that can be absorbed directly from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract into the blood. They are the most rapidly available sources of energy and are the only sugars capable of being used directly to produce energy for the body. Disaccharides such as sucrose (common table sugar), maltose, and lactose are the most common sugars in foods, but they must be metabolized to monosaccharides before being absorbed into the bloodstream. For example, a molecule of lactose is metabolized by the enzyme lactase into a molecule each of glucose and galactose, which are then absorbed through the gut wall into the blood. Complex carbohydrates such as starch, dextrin, and fiber are also known as polysaccharides. Complex carbohydrates must also be metabolized into simple sugars in the intestine before being absorbed. The carbohydrates provide about 4 kcal of energy per gram. Daily caloric needs from carbohydrates range from 3 to 5.5 g/kg/day, depending on energy requirements for daily living, stress, and wound healing. Fruits, grains, and vegetables are excellent sources of carbohydrates. Candies and carbonated beverages are commonly used sources of calories but contain no other nutrients. End products of carbohydrate metabolism are carbon dioxide (excreted primarily through the lungs) and water. A by-product of some complex carbohydrate metabolism is fiber. Until recently, fiber was thought to be only a by-product of carbohydrate metabolism that needed to be eliminated from the body. It is recognized now as a macronutrient, a separate factor necessary for complete nutrition and wellness. Dietary fiber is derived from plant sources and consists of undigestible carbohydrates and lignin and digestible macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins) such as cereal brans, sweet potatoes, and legumes that contribute to overall nutrition. Another category of fiber is functional fiber, which consists of undigestible carbohydrates that have a beneficial physiologic effect on humans. An excellent example of a functional fiber is psyllium, an undigestible fiber that adds bulk to fecal content, which helps timely passage of fecal contents in the GI tract, preventing constipation. Functional fiber content may delay gastric emptying, giving a sense of fullness, which may contribute to weight control. Delayed gastric emptying may also reduce postprandial blood glucose concentrations, potentially preventing excessive insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity. Fibers can reduce the absorption of dietary fat and cholesterol as well as enterohepatic recirculation of cholesterol and bile acids, which may also reduce blood cholesterol concentrations. Total fiber is the sum of dietary fiber and functional fiber. Fats, also known as lipids, serve as the body’s major form of stored energy and are key components of membranes, prostaglandins, and many hormones. They are not water-soluble. Examples of lipids are cholesterol, fatty acids, triglycerides, and phospholipids. Excess dietary carbohydrates and proteins are converted to fat for storage. When used as an energy source, fats generate 9 kcal of energy per gram. Fat intake usually constitutes 25% to 40% of total caloric intake, although the DRIs recommend limits of 20% to 35% from fat. Healthy adults require 1 to 1.5 g/kg/day. Even when patients severely restrict intake for dieting purposes, 4% to 10% of total calories must be supplied in the form of fats to prevent essential fatty acid deficiency. Essential fatty acids (EFAs) are not produced by the body and must be obtained from dietary sources. The most prominent EFAs are omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. They are polyunsaturated fatty acids also known as alpha-linolenic and linoleic acids, respectively. Both fatty acids are required for eicosanoid and prostaglandin production and cell membrane structure. Dietary fats can be subdivided into four categories: monounsaturated, polyunsaturated, saturated, and trans fats (see Box 47-2 for sources of dietary fats). Monounsaturated fats decrease low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) and increase high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) and are considered to be cardioprotective. Polyunsaturated fats also lower LDL and raise HDL levels. Saturated fats raise both LDL and HDL and are thought to increase atherosclerotic plaque formation in the arteries. Only recently has it been recognized that trans fats may induce more heart disease than saturated fats because, in addition to raising LDL cholesterol, trans fats decrease HDL cholesterol and increase triglycerides as well as another undesirable blood fat, lipoprotein(a). Saturated fats and trans fats have no known beneficial nutritional effect and should be eliminated as much as possible from the diet. Note in Figure 47-2 how all plant oils used in food preparation contain saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids. It is recommended that we minimize the use of those oils higher in saturated fatty acids. (See also Chapter 22, p. 344, for further discussion of lipoproteins and cholesterol.) End products of fat metabolism are water and carbon dioxide and insoluble substances excreted in sweat, bile, and feces. Proteins are complex molecules composed of amino acid chains. Amino acids can be subclassified as essential and nonessential. The essential amino acids must be provided from external sources to sustain life; nonessential amino acids can be synthesized to meet metabolic requirements. Before absorption, proteins must be metabolized in the gut to the individual amino acids. Once absorbed, the amino acids are used to build new proteins, such as muscle and other vital tissues, or are used as an energy source if other energy sources are depleted. Amino acids generate 4 kcal of energy per gram, similar to carbohydrates. Sources of highest protein value are dairy products (e.g., milk, eggs, cheese), fish, and meat. Grains and beans have less protein value. End products of amino acid metabolism are nitrogenous products such as urea, uric acid and ammonium, carbon dioxide, and water. Protein requirements for healthy people are 0.5 to 1 g/kg/day. Depending on the amount of stress that the patient is experiencing and the amount of tissue building and wound healing required, protein requirements may range from 1.5 to 2.5 g/kg/day. Calories from proteins generally constitute 12% to 20% of total calorie intake, but the Academy of Sciences recommends 10% to 35% for healthy nutrition. It is crucial that calorie intake be balanced among carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. If there is an inadequate amount of carbohydrates to provide energy to break down the proteins and carbohydrates, the body will actually metabolize body proteins and fats through a process called gluconeogenesis to provide glucose energy to use the incoming proteins and fats. Even though patients are receiving adequate total calories, they may develop a protein-wasting condition. Vitamins, whose name derives from the term vital amines, are a specific set of chemical molecules that regulate human metabolism necessary to maintain health. To be classified as a vitamin, a chemical must be ingested, because the human body does not make sufficient quantities to maintain health, and the lack of a vitamin in the diet produces a specific vitamin deficiency disease (e.g., beriberi is a thiamine deficiency, and scurvy is an ascorbic acid deficiency). To date, 13 compounds have been identified as vitamins, 9 of which are classified as water-soluble and 4 as fat-soluble (Table 47-2). Vitamins were originally named according to letters of the alphabet, but as a result of the diversity of actions of different vitamins, they are commonly referred to by their generic names (e.g., phytonadione is vitamin K, and thiamine is vitamin B1). Table 47-2

Nutrition

Objectives

Key Terms

) (p. 790)

) (p. 790)

) (p. 795)

) (p. 795)

) (p. 795)

) (p. 795)

) (p. 795)

) (p. 795)

) (p. 795)

) (p. 795)

) (p. 795)

) (p. 795)

) (p. 795)

) (p. 795)

) (p. 796)

) (p. 796)

) (p. 796)

) (p. 796)

) (p. 796)

) (p. 796)

) (p. 796)

) (p. 796)

) (p. 796)

) (p. 796)

) (p. 796)

) (p. 796)

) (p. 797)

) (p. 797)

) (p. 797)

) (p. 797)

) (p. 797)

) (p. 797)

) (p. 797)

) (p. 797)

) (p. 797)

) (p. 797)

) (p. 799)

) (p. 799)

) (p. 800)

) (p. 800)

) (p. 800)

) (p. 800)

) (p. 800)

) (p. 800)

) (p. 800)

) (p. 800)

) (p. 801)

) (p. 801)

) (p. 801)

) (p. 801)

) (p. 801)

) (p. 801)

Principles of Nutrition

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

Methods for Assessing Nutrition

Governmental Guidelines

Alternatives to Governmental Guidelines

Counting Calories

Dietary Reference Intakes

Macronutrients

LIFESTYLE

MEN

WOMEN

Sedentary

1.00

1.00

Low active

1.11

1.12

Active

1.25

1.27

Very active

1.48

1.45

PA, Physical activity coefficient.

Vitamins

TYPE OF VITAMIN

ACTIONS

SOURCES

Fat-Soluble Vitamins

Vitamin A (retinol)

Essential for proper vision, growth, cellular differentiation, healthy skin and mucous membranes, reproduction, and immune system integrity; needed to maintain healthy skin and mucous membranes

Deficiency: Night blindness, conjunctival xerosis

Liver, fish liver oils, eggs, whole milk, sweet potatoes, cantaloupe, carrots, spinach, broccoli, raw apricots

Vitamin D (ergocalciferol, D2; cholecalciferol, D3)

Regulates calcium and phosphorus metabolism

Deficiency: Rickets

Liver, cod liver oil, egg yolks, butter and oily fish; produced in skin by exposure to sunlight

Vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol)

Acts as antioxidant; protects essential cellular components from oxidation

Wheat germ oil, sunflower oil, cottonseed oil, safflower oil, corn oil, soybean oil, almonds, peanuts, green leafy vegetables

Vitamin K (phytonadione)

Used for synthesis of prothrombin and factors VII, IX, and X needed for blood coagulation

Needs bile salts to be adequately absorbed in the intestines; malabsorptive disease processes can lead to decreased vitamin K absorption; vitamin K synthesized by intestinal flora; severe diarrhea or use of antibiotics that kill intestinal flora may result in deficiency; deficiency exists in newborn infants

Water-Soluble Vitamins

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid)

Antioxidant; aids in formation and maintenance of intracellular cement substances

Deficiency: Scurvy

Citrus fruits and juices, fruits, and vegetables such as broccoli, cabbage

Niacin (nicotinic acid, vitamin B3)

Used to decrease cholesterol levels; regulates energy metabolism; helps maintain health of skin, tongue, and digestive system

Deficiency: Pellagra

Organ meats, poultry, fish, meats, yeast, bran cereal, peanuts, brewer’s yeast

Riboflavin (vitamin B2)

Affects fetal growth and development; coenzyme for production of mitochondrial energy

Green leafy vegetables, fruit, eggs and dairy products, enriched cereal products, organ meats, peanuts and peanut butter

Thiamine (vitamin B1)

Coenzyme for carbohydrate metabolism; used for nerve conduction and energy production

Deficiency: Beriberi

Pork products, whole grains, wheat germ, meats, peas, cereal, dry beans, peanuts

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6)

Metabolism of amino acids and proteins; may be important in red blood cell regeneration and normal nervous system functioning

Deficiency: Anemia, spotty hair loss, paresthesias

Milk, meats, whole-grain cereals, fish, vegetables

Cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12)

Needed as coenzyme for red blood cell synthesis

Deficiency: Megaloblastic anemia

Seafood, egg yolks, organ meats, milk, most cheeses

Folic acid (folacin)

Essential for cell growth and reproduction, synthesis of DNA in red blood cells

Deficiency: Impaired development of central nervous system; anencephaly, spina bifida

Liver, beans, green vegetables, yeast, nuts, fruit

Biotin

Essential for gluconeogenesis, fatty acid synthesis, metabolism of branched-chain amino acids

Soy flour, cereals, egg yolk, liver; also synthesized in lower gastrointestinal tract by bacteria and fungi

Pantothenic acid (vitamin B5)

Essential for fat, carbohydrate, protein metabolism

Organ meats, beef, and egg yolk ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree