Care of Patients with Substance Abuse Disorders

Objectives

1. Summarize the significance of substance use disorders in the general adult population.

2. List the diagnostic criteria included in the medical diagnosis of substance abuse disorder.

3. Identify the physical, behavioral, and psychological indicators of substance use disorder.

4. Discuss the significance of denial and rationalization in substance use disorder.

5. Analyze the effects of substance use disorders on family and friends.

6. Discuss symptoms and complications of withdrawal from alcohol.

7. Identify at least six nursing interventions appropriate for a patient with a substance use disorder.

Key Terms

abuse (ăb-ūz, p. 1066)

addiction (ă-DĬK-shŭn, p. 1066)

co-dependency (KŌ-dĭ-PĔN-dĕn-sē, p. 1067)

confabulation (kŏn-făb-ū-LĀ-shŭn, p. 1071)

denial (dĕ-NĪ-ăl, p. 1066)

dependency (dĭ-PĔN-dĕn-sē, p. 1066)

detoxification (dĕ-tŏk-sĭ-fĭ-KĀ-shŭn, p. 1069)

dual diagnosis (p. 1066)

enabling (ĕn-Ā-blĭng, p. 1067)

Korsakoff’s syndrome (SĬN-drōm, p. 1071)

psychoactive substances (sī-kō-ĂK-tĭv SŬBZ -tăn-sĕz, p. 1066)

rationalization (ră-shŭn-ăl-ī-ZĀ-shŭn, p. 1066)

substance abuse (SŬBZ-tănz ăb-ŪZ, p. 1065)

substance use disorder (SŬBZ -tănz ūz dĭs-ŎR-dĕr, p. 1065)

tolerance (TŎL-ŭr-ŭns, p. 1066)

Wernicke’s encephalopathy (ĕn-sĕf-ă-LŎP-ă-thē, p. 1071)

withdrawal (p. 1068)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Substance and alcohol abuse

Substance abuse (excessive use of drugs or alcohol that creates problems) has the potential for causing medical problems and death for the patient, and also causes many emotional and physical problems for family, coworkers, and friends. There are many theories about the cause of substance and alcohol abuse. In 1956 alcoholism was recognized by the American Medical Association as a medical disease rather than a moral weakness. However, change in attitude takes time, and there are still many stigmas associated with alcoholism and the abuse of other substances. Research conducted in the mid-1980s identified a genetic predisposition to alcoholism. Neurobiologic theories suggest that some people are born deficient of endorphins (the brain’s own morphine-like substances) or that other people have hormonal influences that make them more susceptible to peer pressure, and so are more likely to abuse substances. Social and psychological theories suggest that users are trying to avoid adult responsibilities and use substances as a dysfunctional coping method. Ongoing research suggests that a variety of factors and circumstances increase the risk for substance abuse: aging (Matthews, 2009), personality disorders (Bates, 2009), male gender (Back et al., 2010), post-traumatic stress disorder (Calhoun et al., 2010), and discrimination against those with lesbian, gay, or bisexual preference (McCabe et al., 2010).

A substance use disorder is diagnosed when individuals have problems with alcoholism or substance abuse. This term implies that there is a recognizable set of signs and symptoms related to the ingestion of a psychoactive substance. Psychoactive substances are any mind-altering agents capable of changing a person’s mood, behavior, cognition, level of consciousness, or perceptions. Abuse of substances is considered maladaptive and nontherapeutic, and manifestation of psychological or physical symptoms implies a dependency on substances. Box 47-1 lists common terms associated with substance use. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) outlines diagnostic criteria. The current definition suggests a substance abuse disorder if, within a 12-month period, the individual repeatedly demonstrates failure to meet usual obligations, creates danger to self or others, has legal problems, or has poor interpersonal relationships because of substance use. As the science of psychiatric diagnosis evolves it is possible that terms such as abuse and dependency will be combined in the general treatment approach of substance use disorder (Bates, 2010). Dual diagnosis indicates that a patient has been diagnosed with a substance abuse problem and with a mental health disorder.

This chapter addresses some of the more commonly abused substances: alcohol, narcotic analgesics, opiates (e.g., heroin) cocaine, amphetamines (includes methamphetamines), nicotine, cannabis (marijuana), hallucinogens (e.g., lysergic acid diethylamide [LSD]), and inhalants.

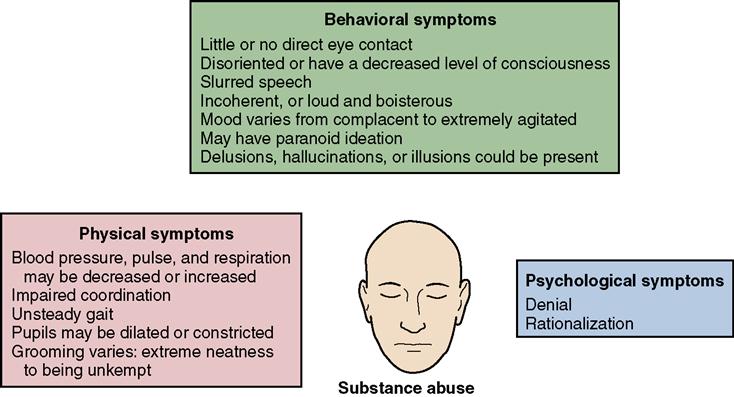

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of substance abuse vary greatly, depending on the substance and on the duration of use and the tolerance that has developed. The patient should be observed for physical, behavioral, and psychological signs (Figure 47-1). Problems with fine motor control may be observed when the individual is trying to perform simple tasks such as walking or eating. Observe the skin for needle tracks, bruises, excessive perspiration, excoriation, or poor condition that suggests malnutrition. Behavioral symptoms (see Figure 47-1) should be compared to baseline; other conditions such as dementia, delirium, and metabolic or psychiatric disorders must be considered if behavioral changes are noted. For psychological symptoms, denial and rationalization are the most common defense mechanisms used by substance abusers. A typical example of denial would be: “I drink a few on the weekend.” A classic example of rationalization is, “I just have a few drinks to relax.” To be effective in treating these patients, you must remember that substance abusers usually do not seek help voluntarily. Denial and rationalization become entrenched behaviors and are difficult to eradicate. A review of defense mechanisms is presented in Table 47-1.

Table 47-1

Table 47-1

| Defense Mechanisms | Characteristics | Example |

| Denial | A simple and primitive defense mechanism. Person ignores reality and absolutely refuses to be swayed by evidence. | An alcoholic states, “I do not have a problem with alcohol. I never drink before 5 P.M.” |

| Rationalization | Justifying a behavior or action by making an excuse or an explanation. | A student states, “I failed the class because the teacher didn’t like me.” |

| Displacement | Discharging intense feelings for one person onto another object or person who is less threatening. | A woman has an argument with her coworker and goes home and kicks the dog. |

| Identification | Modeling behavior after someone else. | A student starts dressing and talking like a popular schoolmate. |

| Intellectualization | Excessive reasoning and logic to counter emotional distress. | A nursing student is upset by the death of a patient, but talks at length about the equipment on the code cart. |

| Reaction-formation | An intense feeling that is unknowingly acted out in an opposite manner. | You treat someone whom you unconsciously dislike in an overly friendly manner. |

| Regression | Returning to an earlier level of behavior when severely threatened. | A 7-year-old child resumes bed-wetting and thumb sucking during the first few days of hospitalization. |

| Repression | Unconsciously blocking an unwanted thought or memory from open expression. | A student truly does not remember cheating on an important test. |

| Splitting | Viewing people or situations as all good or all bad. | A patient praises a nurse one day and then hates and scorns her the next day. |

| Sublimation | Rechanneling an impulse into a more socially desirable acceptable activity. | A student has generalized angry feelings about school so she takes up kickboxing as an after-school sport. |

Effects of Substance Abuse on Family and Friends

Anyone living in proximity to a substance-dependent person will be affected. People who are abusing substances are unavailable for emotional intimacy because life becomes centered on the substance of choice rather than on relationships or responsibilities. Family members experience a multitude of feelings, including anger, rage, embarrassment, guilt, shame, and hopelessness. The family also uses denial and rationalization to cope.

Two terms commonly associated with the family and friends of a substance abuser are enabling and co-dependency. Enabling is “helping” a person so that consequences from unhealthy behavior are less severe; thus, enabling “helps” the unhealthy behavior to continue.

In maintaining their own denial about the situation, enablers cover up for their troubled loved one and attempt to maintain a status quo. Calling in sick for the abuser is one common example of enabling behavior. Enabling keeps the substance-dependent person from facing consequences, and enabling ultimately supports continued denial. Enablers often have a difficult time understanding that their behavior is counterproductive to the health and well-being of the substance abuser and the abuser’s family. Self-righteousness is a typical attitude observed in enablers, and it is difficult to confront.

Co-dependency is another behavior that occurs in circumstances of substance abuse. The co-dependent is any family member or friend who overcompensates and tries to “fix the situation” or to control the substance abuser. For example, a teenage son may repeatedly go to the bar and retrieve his drunk mother when she binges and then assume all household and child care duties until she can function. Because overcompensating does not work, co-dependents feel powerless, and attempt to control even more. A vicious, self-destructive cycle is established that is difficult to break. The overcompensating also keeps the substance abuser from facing reality objectively.

Disorders associated with substance abuse

Alcohol Abuse

Alcohol is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant and is the most commonly abused substance. It is widely available, legally sanctioned, and relatively inexpensive, and abuse of this substance is found at all socioeconomic levels.

Alcoholism is a major health problem and is a factor in many other instances of death and morbidity. Some of the medical conditions include cirrhosis (liver damage), cardiomyopathy, gastrointestinal bleeding, pancreatitis, hypertension, stroke, sleep disturbances, malnutrition, peripheral neuropathies, cognitive impairment, leukopenia (decreased white blood cells), thrombocytopenia (decreased platelets), and chronic infection. Alcohol is also frequently associated with traffic accidents, murder, spousal abuse, child abuse, rape, and suicide. Concurrent abuse of other substances (polysubstance abuse) is frequent. Until alcoholism reaches advanced stages, it is often easy to conceal the problem from the general community. Beginning in early 2010, the Joint Commission conducted a pilot phase to develop and refine Core Measures for the assessment and treatment of alcohol use (see Online Resources).

Symptoms of Intoxication and Withdrawal

A 12-oz bottle of beer, a 6-oz glass of wine, and a 1.5-oz single shot of whiskey contain the same amount of alcohol. It takes approximately 1 hour for the body to metabolize one standard drink. A person is intoxicated when the amount of alcohol ingested creates physical or mental impairment. A number of factors can affect intoxication, such as the quantity and speed of alcohol ingestion; the history of alcohol use (e.g., heavy drinker, novice drinker, social drinker); general health status; and concurrent use of other drugs or substances that depress the central nervous system. Familiar early symptoms that you may have experienced or observed include: drowsiness, slurred speech, loss of coordination, loss of inhibition, euphoria, and mild impairment of judgment. If drinking continues, motor function worsens, confusion progresses, and increasingly stronger stimuli are required to arouse the drinker. The late signs of excessive ingestion include urinary incontinence, coma, low blood pressure, respiratory depression and possibly death (Cohen, 2011).

Withdrawal occurs when a person who has a physical dependence on alcohol stops drinking. Early symptoms of withdrawal may manifest within 6 to 12 hours after the last drink; these include anxiety, irritability, and agitation. Progressive symptoms include increased blood pressure and pulse, tremors, nausea and vomiting, diaphoresis, delirium tremens (“DTs”), hallucinations, and seizures. Major withdrawal symptoms can occur 2 to 3 days after the last drink and may last 3 to 5 days.

Diagnosis

To establish a diagnosis of alcohol dependence, the following criteria must be met: presence of withdrawal, significant impairment in family relationships and occupational productivity, blackouts (a temporary loss of recent memory that occurs while drinking), drinking in spite of serious consequences to health or occupation, and evidence of tolerance.

Making the diagnosis of alcohol dependence is not necessarily difficult. The difficulty lies in getting the patient to admit that there is a problem. Unless there is self-diagnosis (“I am an alcoholic”), treatment will be for the benefit of the treatment team and the family, but will not foster long-term recovery for the patient.

Treatment

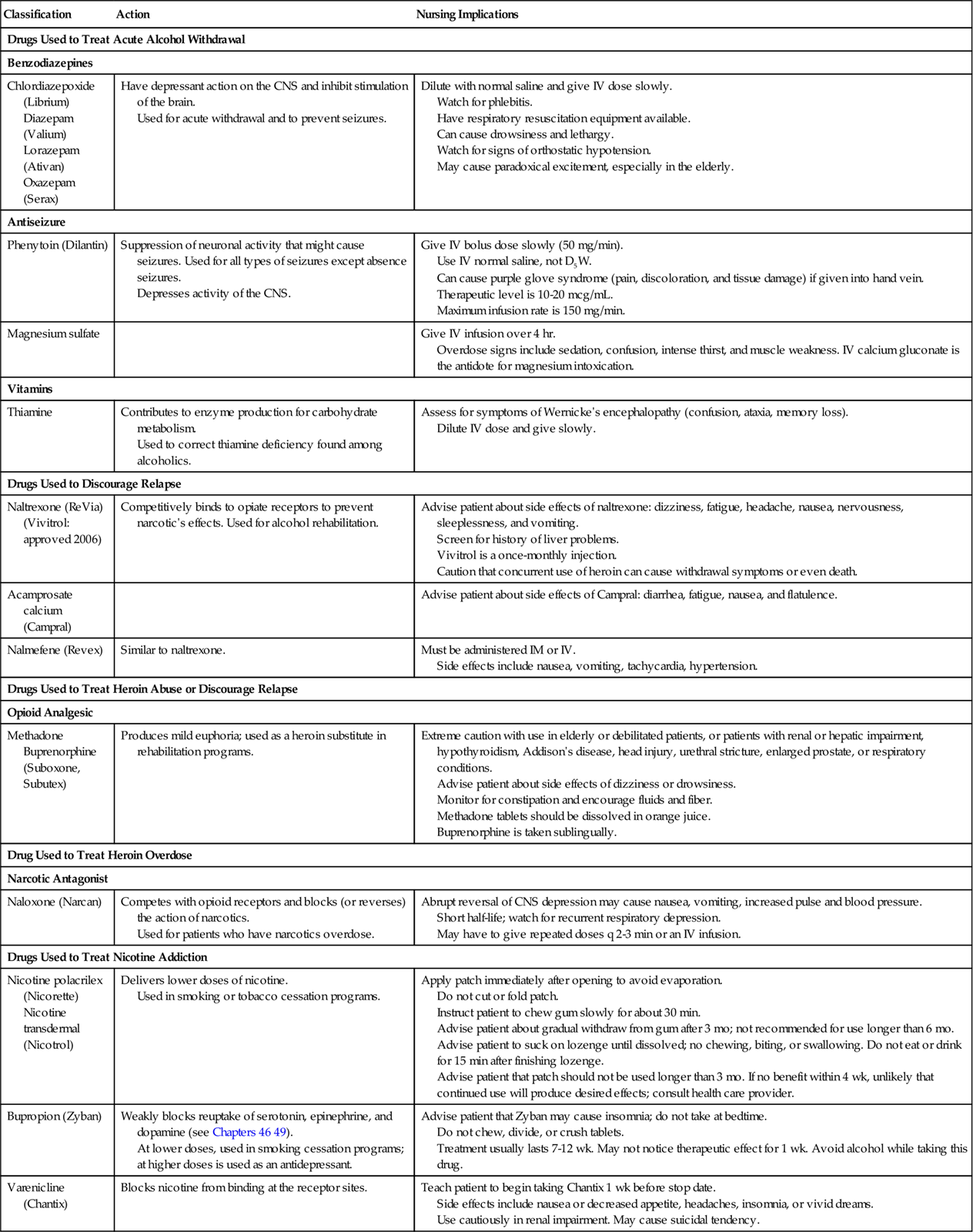

At one time it was thought that allowing alcoholics to experience a painful withdrawal would frighten them so much they would never drink again. Today we know that withdrawal can be life threatening, especially withdrawal from alcohol and certain anxiolytics, such as benzodiazepines. Withdrawal treatment consists of two phases. Initial priorities focus on detoxifying and stabilizing the patient. Detoxification refers to the process of ridding the body of the abused substance, without causing harmful ill effects. Treatment decisions may be based on assessment scales such as the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Scale for Alcohol Revised (CIWA-Ar)  (Clin-eguide, 2009a). CIWA-Ar indicates the severity of the withdrawal and suggests whether admission to the hospital is warranted, or if outpatient treatment is adequate. Chlordiazepoxide (Librium), diazepam (Valium), or oxazepam (Serax) is given in titrated doses. Phenytoin (Dilantin) and magnesium sulfate (if magnesium levels are low) may be given to prevent seizures. Promethazine (Phenergan), prochlorperazine (Compazine), ibuprofen (Motrin), or dicyclomine (Bentyl) may be given for the symptoms of nausea, vomiting, pain, or cramps. Intravenous fluids are used to correct dehydration, and a “banana bag,” which includes normal saline, magnesium sulfate, folic acid, and multivitamins, may be ordered (Tierney, 2009). Table 47-2 lists the medications used to treat substance abuse.

(Clin-eguide, 2009a). CIWA-Ar indicates the severity of the withdrawal and suggests whether admission to the hospital is warranted, or if outpatient treatment is adequate. Chlordiazepoxide (Librium), diazepam (Valium), or oxazepam (Serax) is given in titrated doses. Phenytoin (Dilantin) and magnesium sulfate (if magnesium levels are low) may be given to prevent seizures. Promethazine (Phenergan), prochlorperazine (Compazine), ibuprofen (Motrin), or dicyclomine (Bentyl) may be given for the symptoms of nausea, vomiting, pain, or cramps. Intravenous fluids are used to correct dehydration, and a “banana bag,” which includes normal saline, magnesium sulfate, folic acid, and multivitamins, may be ordered (Tierney, 2009). Table 47-2 lists the medications used to treat substance abuse.

Table 47-2

Table 47-2

Drugs Used to Treat Substance Abuse

| Classification | Action | Nursing Implications |

| Drugs Used to Treat Acute Alcohol Withdrawal | ||

| Benzodiazepines | ||

| Chlordiazepoxide (Librium) Diazepam (Valium) Lorazepam (Ativan) Oxazepam (Serax) | Have depressant action on the CNS and inhibit stimulation of the brain. Used for acute withdrawal and to prevent seizures. | Dilute with normal saline and give IV dose slowly. Watch for phlebitis. Have respiratory resuscitation equipment available. Can cause drowsiness and lethargy. Watch for signs of orthostatic hypotension. May cause paradoxical excitement, especially in the elderly. |

| Antiseizure | ||

| Phenytoin (Dilantin) | Suppression of neuronal activity that might cause seizures. Used for all types of seizures except absence seizures. Depresses activity of the CNS. | Give IV bolus dose slowly (50 mg/min). Use IV normal saline, not D5W. Can cause purple glove syndrome (pain, discoloration, and tissue damage) if given into hand vein. Therapeutic level is 10-20 mcg/mL. Maximum infusion rate is 150 mg/min. |

| Magnesium sulfate | Give IV infusion over 4 hr. Overdose signs include sedation, confusion, intense thirst, and muscle weakness. IV calcium gluconate is the antidote for magnesium intoxication. | |

| Vitamins | ||

| Thiamine | Contributes to enzyme production for carbohydrate metabolism. Used to correct thiamine deficiency found among alcoholics. | Assess for symptoms of Wernicke’s encephalopathy (confusion, ataxia, memory loss). Dilute IV dose and give slowly. |

| Drugs Used to Discourage Relapse | ||

| Naltrexone (ReVia) (Vivitrol: approved 2006) | Competitively binds to opiate receptors to prevent narcotic’s effects. Used for alcohol rehabilitation. | Advise patient about side effects of naltrexone: dizziness, fatigue, headache, nausea, nervousness, sleeplessness, and vomiting. Screen for history of liver problems. Vivitrol is a once-monthly injection. Caution that concurrent use of heroin can cause withdrawal symptoms or even death. |

| Acamprosate calcium (Campral) | Advise patient about side effects of Campral: diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, and flatulence. | |

| Nalmefene (Revex) | Similar to naltrexone. | Must be administered IM or IV. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, hypertension. |

| Drugs Used to Treat Heroin Abuse or Discourage Relapse | ||

| Opioid Analgesic | ||

| Methadone Buprenorphine (Suboxone, Subutex) | Produces mild euphoria; used as a heroin substitute in rehabilitation programs. | Extreme caution with use in elderly or debilitated patients, or patients with renal or hepatic impairment, hypothyroidism, Addison’s disease, head injury, urethral stricture, enlarged prostate, or respiratory conditions. Advise patient about side effects of dizziness or drowsiness. Monitor for constipation and encourage fluids and fiber. Methadone tablets should be dissolved in orange juice. Buprenorphine is taken sublingually. |

| Drug Used to Treat Heroin Overdose | ||

| Narcotic Antagonist | ||

| Naloxone (Narcan) | Competes with opioid receptors and blocks (or reverses) the action of narcotics. Used for patients who have narcotics overdose. | Abrupt reversal of CNS depression may cause nausea, vomiting, increased pulse and blood pressure. Short half-life; watch for recurrent respiratory depression. May have to give repeated doses q 2-3 min or an IV infusion. |

| Drugs Used to Treat Nicotine Addiction | ||

| Nicotine polacrilex (Nicorette) Nicotine transdermal (Nicotrol) | Delivers lower doses of nicotine. Used in smoking or tobacco cessation programs. | Apply patch immediately after opening to avoid evaporation. Do not cut or fold patch. Instruct patient to chew gum slowly for about 30 min. Advise patient about gradual withdraw from gum after 3 mo; not recommended for use longer than 6 mo. Advise patient to suck on lozenge until dissolved; no chewing, biting, or swallowing. Do not eat or drink for 15 min after finishing lozenge. Advise patient that patch should not be used longer than 3 mo. If no benefit within 4 wk, unlikely that continued use will produce desired effects; consult health care provider. |

| Bupropion (Zyban) | Weakly blocks reuptake of serotonin, epinephrine, and dopamine (see Chapters 46 49). At lower doses, used in smoking cessation programs; at higher doses is used as an antidepressant. | Advise patient that Zyban may cause insomnia; do not take at bedtime. Do not chew, divide, or crush tablets. Treatment usually lasts 7-12 wk. May not notice therapeutic effect for 1 wk. Avoid alcohol while taking this drug. |

| Varenicline (Chantix) | Blocks nicotine from binding at the receptor sites. | Teach patient to begin taking Chantix 1 wk before stop date. Side effects include nausea or decreased appetite, headaches, insomnia, or vivid dreams. Use cautiously in renal impairment. May cause suicidal tendency. |

CNS, central nervous system; D5W, 5% dextrose in water; IV, intravenous.

IM, intramuscular.

Once the patient is stable and able to participate in a treatment program, therapy consists of confronting the patient’s denial and encouraging self-diagnosis. Disulfiram (Antabuse) is a drug that causes unpleasant reactions if the patient decides to return to drinking anytime after starting the drug and including 14 days after stopping it. Even small quantities of alcohol that might be inhaled from shaving lotion could trigger serious reactions such as chest pain, nausea and vomiting, hypotension, weakness, blurred vision, and confusion. Naltrexone (ReVia) can be used to block the craving for alcohol and to prevent relapse in the recovery phase; nalmefene (Revex) is similar to naltrexone, but lasts longer and is more potent. An oral form of Revex has been used in research studies, but it is currently only available in parenteral form. Acamprosate (Campral) has been used successfully in Europe and has been approved for use in the United States; patients show significantly higher rates of completing therapy programs on this drug. Vivitrol is a once-monthly injectable form of naltrexone that was approved in 2006.

Group therapy helps break through denial and also gives the patient a new sense of belonging and identity. Behavioral therapy helps with self-discipline and discourages impulsive behavior. Limit setting is one of the hallmarks of behavioral therapy, and it is essential that all members of the behavioral team participate and completely agree about the limits. Brief intervention therapy at 1-year follow-up has been shown to significantly reduce weekly alcohol intake (McQueen  et al., 2009). The acronym FRAMES defines the brief approach: Feedback about personal status, Responsibility to change, Advice for change, Menu for options, Empathy in counseling, and Self-efficacy for changes (Durkin & O’Connor, 2009). In accordance with Healthy People 2020 the use of evidence-based screening in level 1 and 2 trauma centers is essential and brief intervention therapy should be initiated.

et al., 2009). The acronym FRAMES defines the brief approach: Feedback about personal status, Responsibility to change, Advice for change, Menu for options, Empathy in counseling, and Self-efficacy for changes (Durkin & O’Connor, 2009). In accordance with Healthy People 2020 the use of evidence-based screening in level 1 and 2 trauma centers is essential and brief intervention therapy should be initiated.

Referral to a 12-step program, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (A.A.), is also integral to most treatment plans. A.A. has been in existence for over 50 years and is the dominant approach to alcoholism rehabilitation in the United States; although there is no “cure” for alcoholism, there is hope for ongoing recovery. Evidence-based practice shows that active participation in A.A. results in decreased alcohol consumption. Physicians and nurses can assist by helping the patient to make the first call for A.A. information, locating local sites, and asking about the meetings  (Clin-eguide, 2009a). Box 47-2 lists the 12 steps of A.A.

(Clin-eguide, 2009a). Box 47-2 lists the 12 steps of A.A.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Schub, 2009).

Schub, 2009).

2008).

2008).