Care of Patients with Anxiety, Mood, and Eating Disorders

Objectives

1. Analyze the significance of anxiety in the general adult population.

2. Compare and contrast normal anxiety and anxiety disorders.

3. Describe the signs and symptoms and treatment for anxiety disorders.

5. Discuss the variances of normal mood and discuss mood alterations that become debilitating.

7. Summarize factors that are essential when assessing a suicidal patient.

8. Analyze the impact of family, peer, and media pressure on patients with eating disorders.

9. Discuss assessment, nursing diagnoses, and nursing interventions for patients with eating disorders.

Key Terms

affect (ĂF-ĕkt, p. 1052)

anorexia nervosa (ăn-ŏ-RĔK-sē-ă nĕr-VŌ-să, p. 1060)

bipolar disorder (bī-PŌ-lăr dĭs-ŎR-dĕr, p. 1051)

bulimia nervosa (bū-LĒ-mē-ă nĕr-VŌ-să, p. 1060)

dual diagnosis (dū-ăl dī-ăg-NŌ-sĭs, p. 1055)

dysthymia (dĭs-THĪ-mē-ă, p. 1051)

electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (ĕ-LĔK-trō-kŏn-VŪL-sĭv THĔR-ă-pē, p. 1057)

flight of ideas (p. 1051)

generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (jĕn-ĕr-ăl-ĪZD ăng-ZĪ-ĭ-tē dĭs-ŎR-dĕr, p. 1046)

hypersomnia (hī-pĕr-SŎM-nē-ă, p. 1052)

hypomania (hī-pō-MĂN-ē-ă, p. 1051)

insomnia (ĭn-SŎM-nē-ă, p. 1052)

lanugo (lă-NŪ-gō, p. 1061)

major depressive disorder (MĀ-jŏr dĕ-PRĔ-sĭv dĭs-ŎR-dĕr, p. 1055)

mania (MĀ-nē-ă, p. 1051)

obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (ŏb-SĔS-ĭv cŏm-PŬL-sĭv dĭs-ŎR-dĕr, p. 1047)

phobic disorder (FŌ-bĭk dĭs-ŎR-dĕr, p. 1047)

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (pōst-trăw-MĂT-ĭk strĕs dĭs-ŎR-dĕr, p. 1047)

pressured speech (p. 1051)

psychomotor retardation (sĭ-kō-MŌ-tĕr rē-tăr-DĀ-shŭn, p. 1055)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety is considered normal and healthy unless it becomes debilitating and prevents a person from functioning in everyday life. Abnormal or debilitating anxiety is intense and feels life threatening to the individual. One of four people will experience symptoms of an anxiety disorder during his or her lifetime. Elderly people are at high risk for anxiety disorders because of physical illness, psychosocial stress, depression, cognitive impairment, and personal factors related to female gender, lower education, or substance abuse.

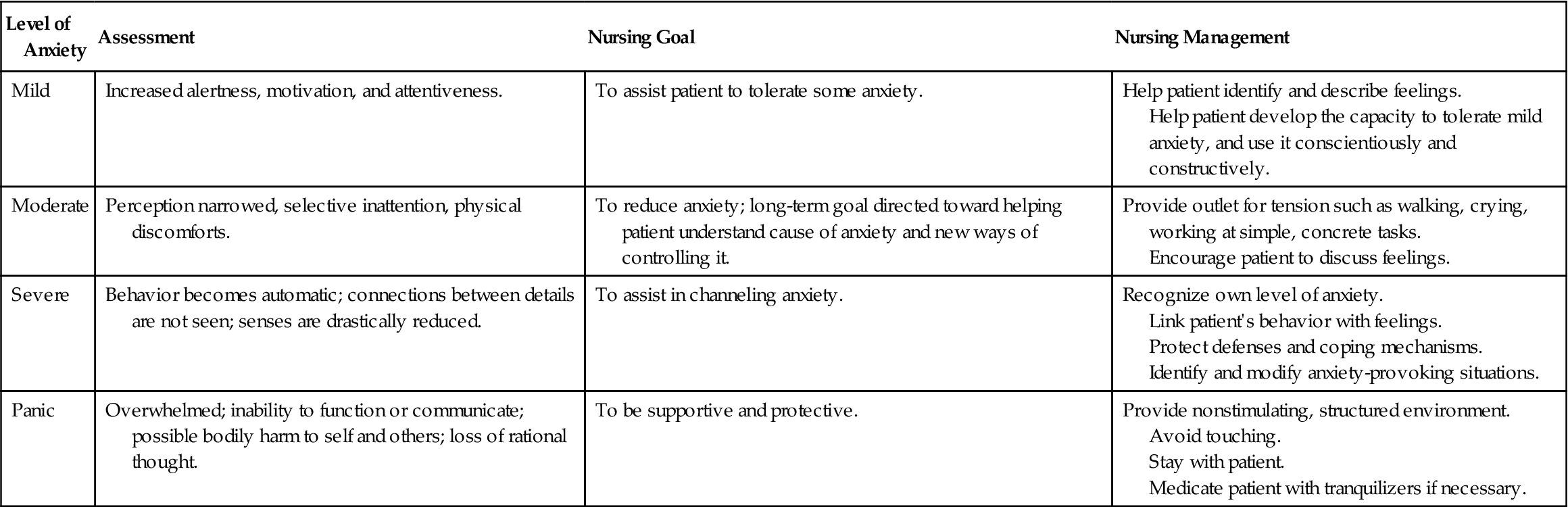

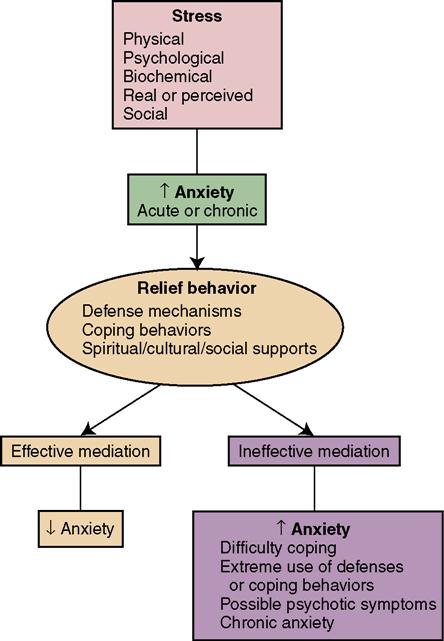

Anxiety is often self-limiting and alleviated without specific medical or nursing intervention. However, intervention may be necessary to prevent potential harm toward self or aggression toward others. Nurses can be instrumental in helping a patient recover from a panic level of anxiety. Table 46-1 describes the various levels of anxiety and their nursing management, and Figure 46-1 depicts the relationship among stress, anxiety, and related behaviors. By remaining calm and supportive, the nurse provides a safety net for the patient. Anticipate that panic-level anxiety is challenging and will often require medication. Patients with anxiety need teaching about how to prevent further attacks. They need to be taught how to relax and should attempt to determine the underlying cause of their anxiety. Anxiety can recur at a greater level of severity; therefore early intervention is important.

Table 46-1

Nursing Management for Levels of Anxiety

| Level of Anxiety | Assessment | Nursing Goal | Nursing Management |

| Mild | Increased alertness, motivation, and attentiveness. | To assist patient to tolerate some anxiety. | Help patient identify and describe feelings. Help patient develop the capacity to tolerate mild anxiety, and use it conscientiously and constructively. |

| Moderate | Perception narrowed, selective inattention, physical discomforts. | To reduce anxiety; long-term goal directed toward helping patient understand cause of anxiety and new ways of controlling it. | Provide outlet for tension such as walking, crying, working at simple, concrete tasks. Encourage patient to discuss feelings. |

| Severe | Behavior becomes automatic; connections between details are not seen; senses are drastically reduced. | To assist in channeling anxiety. | Recognize own level of anxiety. Link patient’s behavior with feelings. Protect defenses and coping mechanisms. Identify and modify anxiety-provoking situations. |

| Panic | Overwhelmed; inability to function or communicate; possible bodily harm to self and others; loss of rational thought. | To be supportive and protective. | Provide nonstimulating, structured environment. Avoid touching. Stay with patient. Medicate patient with tranquilizers if necessary. |

Adapted from Zerwekh, J., & Claborn, J. (2003). NCLEX-PN: A Study Guide for Practical Nursing. Dallas: Nursing Education Consultants (p. 112).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

A person who experiences persistent, unrealistic, or excessive worry about two or more life circumstances for 6 months or longer is exhibiting symptoms associated with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). GAD usually develops slowly and is chronic in nature. As a case study, let us consider John Evans. John Evans has GAD. He worries about his work performance, despite good evaluations. John worries that his children are not happy, smart, popular, or excelling, and he worries constantly about their future. John worries about paying the bills, and he worries about the well-being of his elderly parents. There are currently no actual problems, yet despite his wife’s support and reassurance, John cannot stop worrying. He experiences the signs and symptoms of excessive physiologic response such as tachycardia, restlessness, sweating, fatigue, muscular tension, and shortness of breath. His cognitive symptoms include difficulty with problem solving and poor concentration. John also demonstrates limited coping skills.

Phobic Disorder

A person with a phobic disorder experiences excessive fear of a situation or object. This fear can lead to avoidance or extreme anxiety that interferes with normal responsibilities and routines. As another case study, let us consider Max Payne. Max has a specific type of phobia known as social anxiety disorder. Max is chronically unable to hold a job; he fears scrutiny of his abilities and is afraid of being embarrassed by coworkers or supervisors. Work settings cause him to feel pressured, overwhelmed, and distressed and he experiences physical symptoms such as trembling, blushing, and nausea. He avoids opportunities by creating a variety of excuses not to pursue them, and this further lowers his self-esteem. He acknowledges that his fears are unreasonable, but he continues to make excuses to avoid professional challenges or situations of occupational risk taking.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

When a person has an obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), she experiences an obsession, recurrent or intrusive thoughts that she cannot stop thinking about, and these thoughts create anxiety. A compulsive act is an act that the person feels compelled to perform. For example, a person may experience anxiety and so performs repetitive handwashing in an attempt to reduce that anxiety. Time spent in these thoughts and rituals can become overwhelming to the point of interfering with normal life. Consider the case study of Jane Forman, who is constantly thinking about the boyfriend who left her. Jane does not want to think about him; however, she ruminates (repeatedly talks or thinks about the same topic) on their relationship. She scrubs and cleans everything that he might have touched. Jane begins to miss work and stops socializing with friends because she cannot stop cleaning. Her compulsive thoughts have led to obsessive behavior, and Jane Forman has an obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have endured one or more extreme life-threatening events, and the remembrance of these events now produces feelings of intense horror, with recurrent symptoms of anxiety and nightmares or flashbacks.

As a case study, consider Holly Harris, who was a rape victim 2 months ago. In her consciousness Holly frequently relives the traumatic experience, although she tries to avoid thinking or talking about what happened. She feels detached from others and disinterested in her normal activities. She fears she may not ever be able to have loving feelings toward a man and feels bleak about the future in general. She is irritable and has difficulty sleeping and concentrating. She is hypervigilant, yet she startles very easily.

Diagnosis of Anxiety Disorders

To help clinicians define and diagnose behavioral disorders more consistently, the American Psychiatric Association publishes a regularly updated manual that establishes guidelines for how diagnoses are made. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) provides a set of diagnostic criteria (specific behaviors) and a specific time frame for each mental health disorder. For example, a patient might feel mildly anxious for 1 or 2 days before surgery, but mild anxiety for a short period before such an event would be considered normal; therefore that patient would not meet the criteria for any of the anxiety disorders. In contrast, a person such as John Evans (described previously) is dysfunctional because of continuous worry for at least 6 months and his behavior would meet the criteria for GAD.

The DSM-IV-TR also uses a multiaxial approach that further describes health in physical, social, and functional areas:

• Axis I: Major mental health disorder (e.g., major depression)

• Axis II: Personality disorders or mental retardation (e.g., dependent personality)

• Axis III: Physical health disorders (e.g., diabetes mellitus)

• Axis IV: Psychosocial or environmental factors (e.g., death in the family)

Scores on Axis V (the GAF) range from 1 to 100 for functioning in daily life. For example, many nursing students would score between 81 and 90 because of mild anxiety before tests, but general satisfaction with life; whereas many people in jail would score below 50 because of a prolonged inability to hold a job, with history of legal problems and social dysfunction.

Treatment of Anxiety Disorders

People with anxiety disorders can be treated with supportive therapy and anxiolytic (antianxiety) medications. Supportive therapy may include individual therapy and education about relaxation techniques and stress management. Patients who are anxious need much reassurance, and a nurse who is nonjudgmental will be a good listener. Evidence-based practice indicates that for elderly patients with GAD, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the first-line psychotherapy (Box 46-1).

A relatively new short-term therapy for PTSD is eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR). In EMDR, while the patient thinks about the distressing event, she shifts her gaze from one side to the other. As unpleasant feelings are uncovered, the therapist redirects the eye movements and this helps the patient to release the emotions. In another new therapy for PTSD, the patient wears a headset and is exposed to a virtual reality environment. The clinician controls what the patient hears, sees, and smells, and the patient learns to tolerate anxiety (Helwick, 2010).

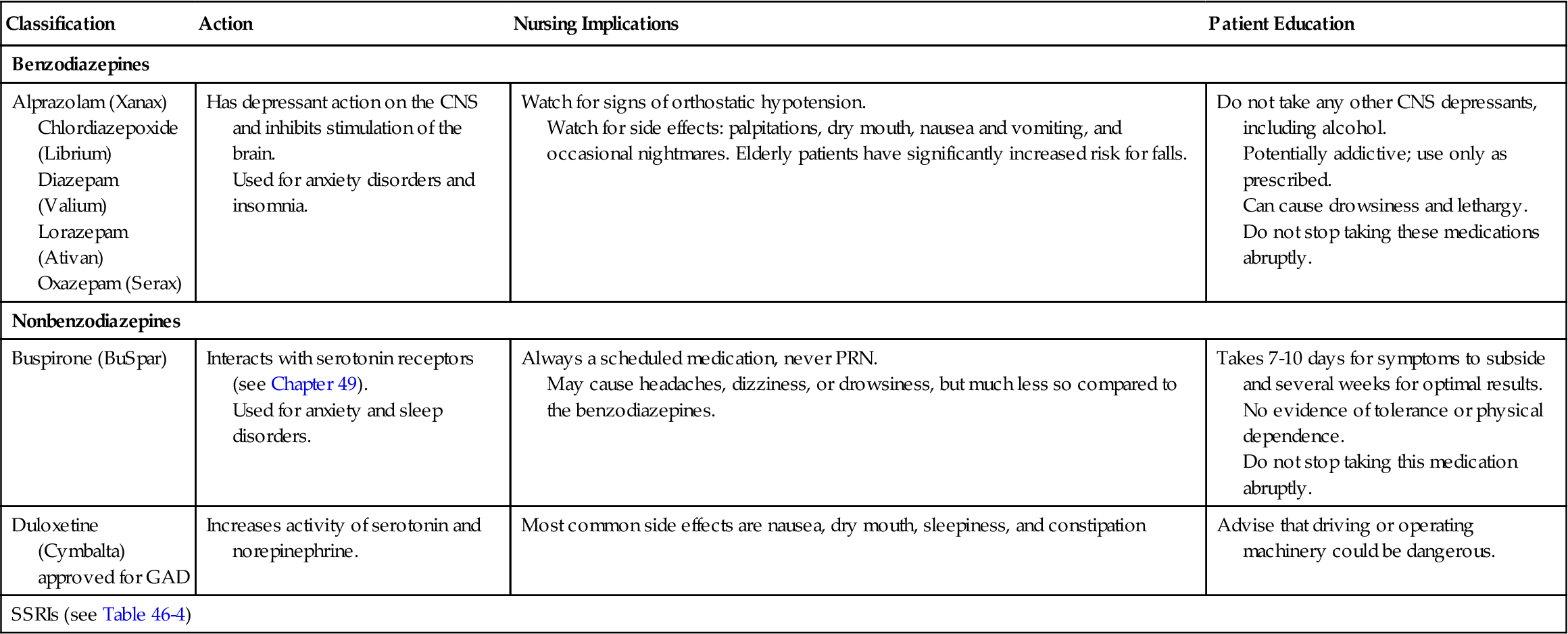

Benzodiazepines are commonly prescribed for anxiety disorders. Drugs from this category are alprazolam (Xanax), chlordiazepoxide (Librium), oxazepam (Serax), lorazepam (Ativan), and diazepam (Valium). Patients taking these drugs must be advised to use medications with caution because tolerance (the need for an increased dosage to achieve the desired effect) and physical and psychological dependency can occur.

Buspirone (BuSpar), in a class by itself, takes 3 to 4 weeks to reach therapeutic efficacy. The advantage of BuSpar is less sedation with a decreased risk of dependency. Another class of drugs, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), are becoming first-line drugs for anxiety because they have fewer adverse effects. Examples from the SSRI category include citalopram (Celexa) and sertraline (Zoloft). Table 46-2 presents a list of common medications used to treat anxiety.

Table 46-2

Table 46-2

Medications Used to Treat Anxiety

| Classification | Action | Nursing Implications | Patient Education |

| Benzodiazepines | |||

| Alprazolam (Xanax) Chlordiazepoxide (Librium) Diazepam (Valium) Lorazepam (Ativan) Oxazepam (Serax) | Has depressant action on the CNS and inhibits stimulation of the brain. Used for anxiety disorders and insomnia. | Watch for signs of orthostatic hypotension. Watch for side effects: palpitations, dry mouth, nausea and vomiting, and occasional nightmares. Elderly patients have significantly increased risk for falls. | Do not take any other CNS depressants, including alcohol. Potentially addictive; use only as prescribed. Can cause drowsiness and lethargy. Do not stop taking these medications abruptly. |

| Nonbenzodiazepines | |||

| Buspirone (BuSpar) | Interacts with serotonin receptors (see Chapter 49). Used for anxiety and sleep disorders. | Always a scheduled medication, never PRN. May cause headaches, dizziness, or drowsiness, but much less so compared to the benzodiazepines. | Takes 7-10 days for symptoms to subside and several weeks for optimal results. No evidence of tolerance or physical dependence. Do not stop taking this medication abruptly. |

| Duloxetine (Cymbalta) approved for GAD | Increases activity of serotonin and norepinephrine. | Most common side effects are nausea, dry mouth, sleepiness, and constipation | Advise that driving or operating machinery could be dangerous. |

| SSRIs (see Table 46-4) | |||

In a new experimental therapy for anxiety disorders, propranolol was used to decrease the fear associated with a frightening memory. Researchers found that the timing of the drug in relation to the threatening event was the essential element. Other studies suggested that well-timed psychotherapy could potentially be used instead of the drug to accomplish the manipulation of the memory and fear response (Harvard Medical School, 2009).

Nursing Management

Assessment (Data Collection)

You should assess the anxiety-prone patient for subjective feelings of fear, apprehension, isolation, or the need for increased space. Assess the patient’s ability to concentrate and make rational judgments, and explore the sources of preoccupation and worries. Physical symptoms may include trembling, feeling shaky, increased muscle tension, muscle soreness, easy fatigability, and restlessness. Patients may be hypervigilant, have difficulty sleeping, and be very irritable. In addition, an autonomic nervous system response can cause an increase in blood pressure, dyspnea, palpitations, dry mouth, dizziness, and nausea.

Evidenced-based guidelines suggest that screening tools can be used by any health care worker if an elderly patient is showing signs of an anxiety disorder. These assessment tools include the Mini-Mental State Examination (see Chapter 48), Geriatric Anxiety Inventory, Short Anxiety Screening Test, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and Rating Anxiety in Dementia Scale (Smith & Brighton, 2009).  After initial screening, the physician is notified, to determine the diagnosis.

After initial screening, the physician is notified, to determine the diagnosis.

Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing diagnoses for anxiety include:

• Anxiety related to threat to self-concept

• Fear related to threat in the environment

• Impaired social interaction related to extreme anxiety in social situations

• Ineffective coping related to panic attack

• Ineffective role performance related to perceived inability to complete work responsibilities

• Powerlessness related to loss of control when facing a specific phobic object (e.g., a spider)

• Complicated grieving related to multiple loss of fellow soldiers (i.e., war trauma)

• Post-trauma syndrome related to an overwhelming, life-threatening event (e.g., rape)

Planning

Expected outcomes are written for the specific individual nursing diagnoses chosen to resolve the patient’s problems. For the nursing diagnoses above, example outcomes might include:

• Patient will demonstrate decreased symptoms of anxiety (e.g., pacing, crying) within 3 days.

• Patient will verbalize feelings of safety before discharge.

• Patient will attend group meeting today accompanied by primary nurse.

• Patient will practice three coping strategies to use during a panic attack before discharge.

• Patient will identify three tasks at which she excels at work, during this shift.

• Patient will verbalize increased feelings of control when encountering phobic object within 1 month.

• Patient will express grief and loss related to multiple losses before discharge.

• Patient will experience fewer nightmares related to traumatic event within 3 months.

Planning care for a patient with an anxiety disorder involves promoting a physically and psychologically safe environment. For example, provide a quiet, clean, and noncluttered environment and verbal reassurance (“Mrs. Smith, you are safe here. The staff is here to help you.”). Methods to reduce the symptoms of anxiety include therapeutic communication, such as active listening, being physically present, offering emotional reassurance, giving clear and concise instructions, and using pharmacologic methods.

As the acute anxiety passes, the focus of care is to help the patient recognize that certain behaviors (such as avoidance) are being overused. The patient is then assisted to develop new methods of coping and to resume participation in family, social, and occupational roles.

Implementation

When intervening with a patient who is experiencing extreme levels of anxiety, you must maintain a calm and reassuring attitude. Stay with the patient and attend to physical needs as necessary. Attempt to make the immediate surrounding environment less stimulating. For example, dim the lights, turn off the television or radio, and limit the number of people in the area. Be sure to use clear, simple statements, and repeat them as necessary. When extreme levels of anxiety resolve, use additional interventions to help the patient learn to control her anxiety (see Table 46-1).

When the anxiety is under control, you can assist in helping the patient to use problem-solving strategies. The long process of determining root causes of the anxiety can take years of therapy, but you can make referrals as needed, and provide support.

Evaluation

Ongoing evaluation of patients with anxiety is necessary. Evaluation includes the status of the patient before discharge from the hospital, clinic, or emergency department. Carefully document that outcome criteria were met and symptoms were relieved. If symptoms are not totally resolved, you should clearly document that the patient’s level of anxiety is not a threat to self or others at the time of discharge. Also include the plan for follow-up care and a plan to obtain emergency care if needed.

Mood Disorders

The incidence of mood disorders is very high. Unfortunately, these disorders are often inaccurately diagnosed and treated. Dysthymia refers to a disturbance in mood that may manifest in either depression or elation (mania). An individual experiencing clinical depression is more than just sad. Depressed or dysthymic individuals feel a sense of hopelessness and despair that cannot be alleviated by usual means. This hopelessness can lead to thoughts of suicide.

Mania is an elevation in mood that includes increased grandiosity or irritability that is present for at least 1 week. A manic person may exhibit pressured speech, which is talking that is loud and rapid and difficult to interrupt; or flight of ideas, where the speaker goes from topic to topic with little or no connection. There is an inability to concentrate, a decreased need for sleep or nutrients, and an increase in goal-directed activity, impulsive spending, and hypersexuality. Unstable and frequently changing, or labile, behavior is often seen in manic patients; a mood of frivolity and joking can rapidly change to agitation and extreme paranoia. The agitation and irritability seen in manic patients can often lead to aggressive behavior. Manic individuals may require hospitalization for an inability to eat or sleep for days that leads to complete physical and mental exhaustion and aggressive behavior. Sometimes individuals will rapidly switch from being extremely depressed to being euphoric and manic. This condition is called bipolar disorder and occurs equally in men and women. It often is initially diagnosed in young adults, but it may be diagnosed at any time during the life span.

Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is suspected when a patient experiences episodes of extreme sadness, hopelessness, and helplessness interspersed with periods of extreme elation and hyperactivity. According to the DSM-IV-TR, two types of bipolar disorder are recognized. Bipolar I disorder is characterized by episodes of major depression with at least one episode of manic or hypomanic behavior. Bipolar II disorder is characterized by one or more depressive episodes with at least one episode of hypomania. Hypomania is an inflated or irritable mood for at least 4 days. Patients may display loud, rapid speech, and flight of ideas, decreased need for sleep, distractibility, and an increase in goal-directed activity, but hospitalization is not indicated because it does not involve psychotic behavior.

Treatment

Lithium carbonate is the drug of choice used to stabilize manic behavior. Lithium has a narrow therapeutic range, so serum lithium levels must be determined 8 to 12 hours after the first dose, then two or three times per week for the first month, and then weekly to monthly. See Table 46-3 for nursing implications for lithium. Because it may take 2 to 3 weeks for lithium to become effective, antipsychotics such as chlorpromazine (Thorazine) or haloperidol (Haldol) are given to decrease the initial level of hyperactivity. Anticonvulsant drugs such as divalproex sodium (Depakote) and carbamazepine (Tegretol) are effective in the treatment of mania and quetiapine (Seroquel), which is an atypical antipsychotic (see Box 49-1 and Table 49-2), is also used for mania. Lamotrigine (Lamictal) is effective for the depressive episodes. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved risperidone (Risperdal Consta) (2008) and ziprasidone HCl (Geodon) (2009) for treatment of bipolar disorder. All of these can be used safely in combination with lithium. In addition to stabilizing the patient with medication, it is sometimes necessary to hospitalize patients with manic symptoms, particularly if they are a danger to themselves or others, or are suffering from exhaustion caused by extreme hyperactivity. Recently, Diazgranados and colleagues (2010) used one dose of intravenous ketamine (Ketalar) with treatment-resistant bipolar depression, and subjects showed improvement in 40 minutes.

Table 46-3

Table 46-3

Nursing Implications for Patients on Lithium

| Classification | Action | Nursing Implications | Patient Teaching |

| Antimanic | Alters the release, synthesis, and reuptake of neurotransmitters in the brain (i.e., dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin) (see Chapter 49). Does not cure bipolar disorder, but helps to decrease the manic behavior. | Takes 7-14 days to reach therapeutic level (1.0-1.5 mEq/L). Blood levels should be drawn 8-12 hr after the first dose, then two or three times/wk for the first mo and then weekly to monthly until a maintenance level is reached. Sodium depletion or dehydration could cause toxicity; therefore monitor fluid intake and dietary sodium. Diuretics should be avoided. Monitor renal and thyroid function periodically. | Normal salt intake. Drink 2500-3000 mL of fluids per day. Take with meals to decrease gastric distress. Avoid caffeinated drinks because of diuretic effects. Immediately report diarrhea, vomiting, tremors, or lack of coordination. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree