Care of Patients with Trauma or Shock

Objectives

1. List the basic principles of first aid.

3. State the key components of assessing a trauma patient.

4. Discuss prevention of injuries from extremes of heat and cold.

6. Describe emergency care of victims of insect stings, tick bites, and snakebites.

8. Identify signs and symptoms of shock.

9. Compare and contrast the treatment of cardiogenic, hypovolemic, and neurogenic shock.

1. Observe how the triage nurse in the emergency department sets priorities for patient care.

2. Observe how the emergency team works together on a major accident victim.

3. Role play with fellow students, practicing techniques to calm a combative patient.

Key Terms

anaphylaxis (ă-nă-fă-LĂK-sĭs, p. 1031)

angioedema (ăn-jē-Ō-ĕ-DĒ-mă, p. 1036)

automated external defibrillator (AED) (ĂW-tō-mā-tĕd ĕks-tĕr-năl dē-fĭb-rĭ-LĀ-tŏr, p. 1033)

C-A-B (chest compressions, airway, breathing) (p. 1032)

flail chest (p. 1032)

hands-only CPR (p. 1032)

hypovolemia (hī-pō-vō-LĒ-mē-ă, p. 1033)

index of suspicion (p. 1022)

mechanism of injury (p. 1022)

multisystem organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (p. 1038)

perfusion (pĕr-FŪ-zhŭn, p. 1033)

poison control center (p. 1029)

push hard, push fast (p. 1033)

shock (shŏk, p. 1033)

systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (p. 1038)

triage (TRĒ-ăhzh, p. 1022)

vasoactive (vă-zō-ĂK-tĭv, p. 1036)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Prevention of Accidents

Home Safety

According to statistics compiled by the National Safety Council (2010), accidents in the home account for one half of all unintentional injury deaths. People under 5 and over 65 years of age are the principal victims of fatal mishaps occurring in the home. The two most dangerous rooms in the house are the kitchen and the bathroom (Box 45-1).

Highway Safety

Motor vehicle accidents are the leading cause of accidental death in the United States. Improper driving, which is responsible for almost 90% of all accidents, can be caused by the influence of alcohol and/or drugs, fatigue, excessive speed, distractions, or emotional instability. Emphasis on using seatbelts, better enforcement of laws against driving drunk, and discouraging use of cell phones have helped to decrease accidents. Improvements in emergency medical services (EMS) and care of accident victims have significantly decreased vehicular deaths.

Water Safety

Water safety rules include selecting safe swimming areas, ensuring supervision of children and adults who are not strong swimmers, diving where the water is sufficiently deep and is free of rocks or obstacles, never swimming alone, and avoiding swimming distances beyond one’s ability. The victim of a diving injury preferably should not be removed from the water until EMS arrives, because of possible neck and spinal cord injury. The victim is placed on a flat surface and is moved as a unit, taking care to rigidly stabilize the neck. Venema and colleagues (2010) reviewed 29 rescue reports and concluded that bystander intervention makes a critical difference in the survival of drowning victims. First, the rescuer should call for help. If possible, try to reach the victim without going into deep water. After the rescued person is brought out of the water, he must be given cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and rescue breathing if he is not breathing and is pulseless. If he is breathing, he should be placed on his side (Figure 45-1) and his head should be turned to one side to prevent aspiration. Near-drowning victims should be transported to a medical facility. They usually aspirate water, and pulmonary edema may occur. Bacterial or fungal pneumonia may follow aspiration of fresh water. There is danger of delayed cardiac irregularities for any victim who struggled in the water.

First Aid and Good Samaritan Laws

First-aid providers must proceed step-by-step. Deliberate action will help to instill confidence in those you are trying to help. Table 45-1 shows guidelines for first aid. Most states have adopted “Good Samaritan” laws that protect medical personnel from liability when rendering emergency medical care for victims of accidental injury. These laws guard against liability for care, as long as medically trained individuals act in good faith and to the best of their ability. Individuals who offer care are held to the standard of care consistent with their level of training. If a nursing assistant stops to provide emergency care, she will be held to a different standard than the physician who stops at the same accident scene. Both are expected to do the best they can in the circumstances. A bad outcome is not proof of improper care. Even in states in which there are no such protective laws, malpractice suits of this kind very rarely occur.

Table 45-1

General Principles of First Aid

| Action | Reasoning |

| Before attending to the victim or victims of an accident, quickly survey the accident scene to determine whether there are further hazards to yourself and the victims. | Spillage of gasoline after a motor vehicle accident can cause a fire or explosion, or there may be danger to the victim, yourself, and onlookers from oncoming traffic and secondary collisions. In both highway and home accidents, live electrical wires may be in the vicinity. Whenever there is a high risk of death from hazardous conditions in the immediate environment, the victims should be moved at once, regardless of the nature of their injuries. Victims may receive severe burns from lying on a sun-baked street or sidewalk while waiting for the ambulance. Although it may not be safe to move the victim to a shaded area, it is advisable to place clothing, newspaper, or some other protective covering between skin and the hot pavement. |

| If there are several victims of the accident, make a quick check on each one before beginning treatment. | The most serious and life-threatening injuries must be treated first; those victims who do not seem to be in immediate danger can be attended to by someone else who is capable of watching them and reporting any change in their condition. |

| Use a calm tone and short sentences to explain what you are doing. You must sound as if you are in control of yourself and the situation. | Giving reassurance to the victim will decrease anxiety and promote cooperation. Using short, simple explanations facilitates understanding during duress. Forcing yourself to remain calm can increase your own ability to function in an emergency situation. |

| Do not move the victim unless he is in immediate danger or until you have immobilized injured parts. | This is particularly true if spinal injury is suspected. Moving the victim can cause further injury if precautions are not taken. |

| Do not remove an object that has penetrated a part of the body and is still in place. | A knife, piece of metal, or sliver of wood that is protruding from the chest or abdomen should be left as is until it can be removed in a controlled situation by trained professionals. Removal of the object can cause further damage and make bleeding worse. Bandages are applied around the object to stabilize it and control bleeding as necessary. |

| Look for a Medic-Alert bracelet or necklace. | If the victim is wearing one or has some other identification showing specific medical needs, bring this to the attention of the ambulance or hospital personnel. |

| Try to determine the mechanism of injury. | This will give clues about the type of injury sustained and the treatment required. When evaluating the victim, begin at the head and work downward to the toes (see Focused Assessment on p. 1023). |

| Do not try to give anything by mouth to a person who is unconscious or has a decreased level of consciousness. | Aspiration of the material into the air passage may occur, causing breathing difficulty or complete airway obstruction. |

| Give an organized and chronological report to the EMS or physician, including details of incident (if you were a witness), assessment of injuries, and care rendered. | Any details of events leading to incident, mechanism of injury, baseline assessment data, and care rendered will be useful in the emergency care at the hospital. Being brief and organized is important because the EMS personnel must simultaneously intervene and take a history if the victim is in critical condition. |

Emergency Care

The nurse may need to give emergency care in a variety of community, clinic or hospital settings, but emergency nursing is generally associated with care of patients in the emergency department (ED) of a hospital. In a survey of hospital ED directors, 90% said that overcrowding and long wait times are an issue. One of the Healthy People 2020 objectives is to reduce the proportion of patients that wait beyond the recommended time frame to see an emergency physician. A new Joint Commission’ Core Measure holds hospital facilities accountable for the “latest time the patient was receiving care in the ED, under ED services or awaiting transport.” An increased number of uninsured patients and downsizing of hospitals contribute to overcrowding, which leads to decreased patient satisfaction, frustration for health care personnel, and increased risk for poor outcomes. In a study of 4574 patients who were admitted for chest pain, the authors concluded that serious complications were three to five times more likely to occur if they were treated in a crowded ED (Pines et al., 2009). Two problems were identified: more than 43% of ED patients are nonurgent, and there are significant transfer delays for those who need to be admitted to an inpatient bed (Olshaker, 2009); thus all health care professionals must work toward educating patients about appropriate use of emergency services and the entire hospital administration and staff must support the timely transfer of ED patients to inpatient beds.

Emergency nurses need excellent assessment and clinical decision-making skills and the ability to prioritize care under stressful conditions. Frequently emergency nurses follow protocols to initiate diagnostic testing or to start therapy, such as oxygen administration or peripheral intravenous access. Clinical decisions, prioritization, and use of protocols are based on (1) events or incidents that preceded the emergency visit, (2) mechanism of injury, and (3) index of suspicion. For example, two patients arrive at the hospital in an unresponsive state. For the first patient, friends report, “She was drinking and taking a lot of drugs for fun and then we found her passed out with vomit on her mouth.” For the second patient, bystanders report hearing him complain of chest pain and needing his heart medication and finding him unresponsive in the parking lot. Both patients are unresponsive, but preceding events suggest that the first patient is an overdose with possible aspiration, whereas the second is more likely to have an acute cardiac problem.

Mechanism of injury refers to how the injury occurred; an experienced clinician may use this information to predict damage and complications. For example, toddlers frequently sustain dramatic looking “goose eggs” on the forehead by falling against a coffee table, but these incidents are usually more traumatic for the parents than the child. A high index of suspicion is required to detect problems that are not initially obvious. For example, a patient reports being kicked and punched several times in the abdomen. At first the patient appears to be stable with minor abrasions; however, this patient will require serial abdominal assessments to detect slow hemorrhage or internal tissue damage. Maintaining a high index of suspicion is important in a busy emergency setting, because everyone (including the patient) is anxious for discharge or transfer to make room for others in the waiting room.

Triage: Initial Survey

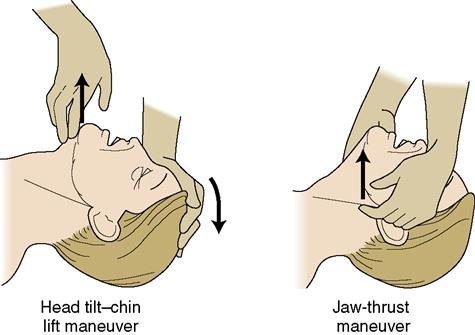

The process of setting priorities for treatment is known as triage. One of the most common methods for triage of patients uses “ABCDE” as a memory trigger for the sequence of assessment. A is airway, B is breathing, and C is circulation. D can mean either the need for defibrillation or, in a trauma setting, assessment of neurologic disability. E is exposed: all areas of the body should be exposed so that injuries are not missed underneath clothing.

Airway and Respiration

A patent airway and oxygenation are priority. A simple way to assess airway is to ask the person to tell you his name and to ask how he is feeling. If the airway is partially obstructed, the voice quality may sound muffled or coarse. With severe shortness of breath, a person cannot complete full sentences. A confused answer suggests possible decreased cerebral perfusion and oxygenation. If the patient is unconscious, look for the rise and fall of the chest.

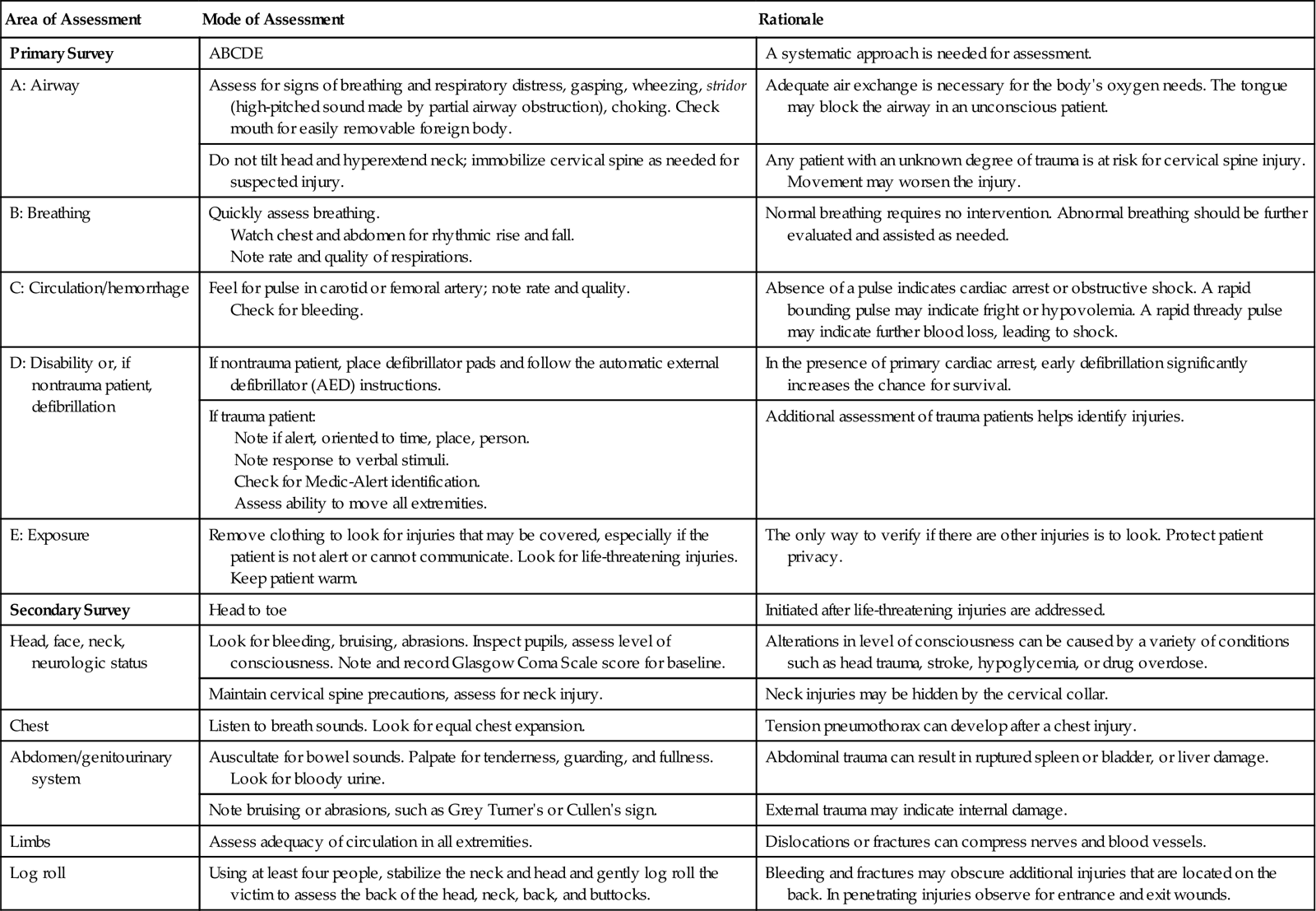

The most common cause of airway obstruction in the unconscious person is the tongue. The head tilt–chin lift maneuver repositions the trachea and tongue and opens the airway. The jaw thrust method should be used if a spinal injury is suspected. For this, position yourself at the head of the victim; place your elbows on either side of the head, and place your thumbs on his lower jaw near the corners of the mouth and pointing toward his feet; place your fingertips around the bone of the lower jaw, and lift (Figure 45-2 on p. 1024). (Note: Jaw thrust is no longer taught to the lay rescuer; however, health care professionals must learn this maneuver.)

After ensuring that the airway is patent, take a pulse oximetry reading and apply oxygen as needed and monitor respiratory rate and effort. Emergency equipment for resuscitation and intubation should be checked every day and use of the equipment should be reviewed periodically.

Control of Bleeding

Severe bleeding can rapidly lead to irreversible hypovolemic shock. Arterial blood is bright red and gushes in spurts at regular intervals. Blood from a severed or punctured vein leaks slowly and steadily and is dark red. Even major bleeding can usually be stopped by applying pressure  directly over the wound. When in a health care work setting, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Occupational Safety and Health Administration requirements mandate use of personal protective equipment that includes barrier devices such as gloves when in contact with body fluids. In a community setting, adapt available material.

directly over the wound. When in a health care work setting, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Occupational Safety and Health Administration requirements mandate use of personal protective equipment that includes barrier devices such as gloves when in contact with body fluids. In a community setting, adapt available material.

The palm of the hand is used, preferably after a clean cloth or sterile dressing has been placed over the open wound. However, if no dressing is available and the blood loss is substantial, contamination of the wound is not as important as controlling the hemorrhage. Once the bleeding has stopped, a compression dressing and bulky bandage are applied and left in place to prevent disturbing clots. If blood soaks through the original dressing, additional dressings are applied over the soaked ones. The wrap should not completely constrict circulation. Elevating and immobilizing the injured part will help to control bleeding.

If bleeding is copious and cannot be stopped with a pressure bandage and immobilization, the artery leading to the wound can be compressed to decrease or even stop the flow of blood. Pressure points for control of arterial bleeding are shown in Figure 16-3. If compression of the pressure point is successful, the distal pulse will be absent and the victim will notice a tingling and numbness in the area. Compression of pressure points on the neck and head should be avoided unless there is no other choice because of interference of the blood supply to the brain.

Neck and Spine Injuries

Presence of neck or spinal injury should be suspected in any situation in which the individual has sustained multiple injuries, a fall, or is unconscious. Examples of accidents which would increase index of suspicion for spinal injury include motor vehicle collisions, diving, biking, or any situation in which the neck receives significant force. In emergency or accident situations, the rescuer may be distracted by severe bleeding or other life-threatening conditions and thus overlook the possibility of a spinal cord injury.

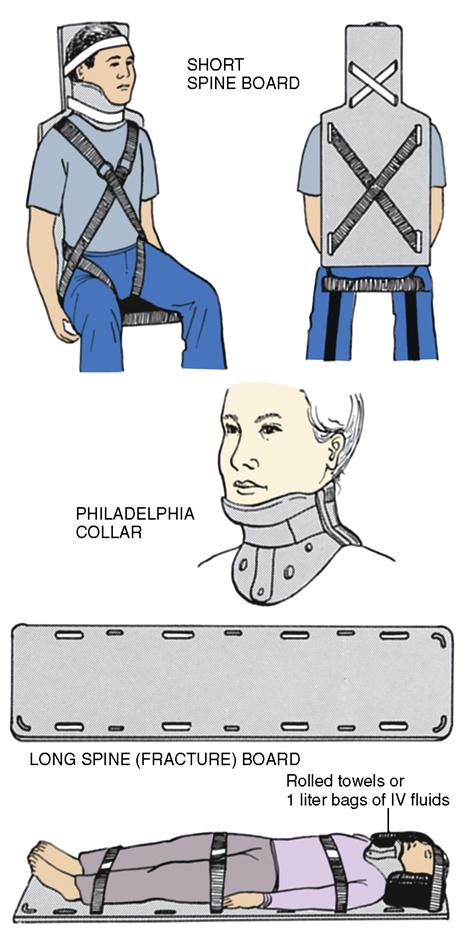

If the victim must be moved to safety before EMS arrives, the neck may be immobilized with a coat, or towel, rolled in the shape of a collar. The purpose is to keep the neck as straight as possible, preventing it from flexing or hyperextending. Applying a cervical collar or other commercial device and maintaining traction on the head requires advanced training (Figure 45-3). A cervical collar is not particularly comfortable for the patient and it partially obscures assessment of the neck, jaw, and upper mid-chest but removal of the collar is strictly at the discretion of the physician (see Chapter 23).

Chest Trauma

Thoracic trauma is a major cause of accidental death, exceeding head and facial injuries. There also can be contusion of the myocardium, rupture of the aorta, and tracheobronchial or tracheoabdominal injuries.

Fractured ribs are very painful, as breathing causes movement at the site of injury. The treatment goal is to decrease pain so that the patient can breathe adequately. Intercostal nerve block with local anesthesia may be used to control pain. Narcotic drug therapy is used cautiously since it can depress respirations. Binding the ribs is no longer recommended.

When three or more ribs are broken in two or more places, the chest wall becomes unstable. This condition is called flail chest, which produces paradoxical respirations. When the patient breathes in, the fractured portion of the chest is drawn inward instead of expanding outward as the rest of the chest does; with exhalation, the flail portion expands outward as the rest of the chest collapses normally. This process interferes with oxygenation, as the lungs cannot expand normally. Emergency treatment consists of turning the patient onto the affected side so that the ground or bed will act as a splint and reduce the pain of breathing. The patient is observed for signs of external and internal bleeding, pneumothorax, and shock.

Once the patient is in an emergency facility, flail chest is treated by intubation and mechanical ventilation while the ribs heal. The patient often has to be given a neuromuscular blocking agent such as pancuronium bromide (Pavulon) to prevent fighting the action of the ventilator. Sedation and pain medication are used to decrease anxiety over being totally paralyzed.

Pneumothorax, Hemothorax, and Tension Pneumothorax

An open, or “sucking,” chest wound is one in which pneumothorax (accumulation of air), or hemothorax (accumulation of blood) results from penetration of the pleural cavity. Symptoms of pneumothorax or hemothorax include labored, shallow respirations, lack of movement on one side of the chest when the person inhales and exhales, and chest pain. In the field, emergency medical personnel will cover a sucking chest wound at the end of a forceful expiration with an occlusive dressing—that is, one made of plastic wrap, aluminum foil, Vaseline-covered gauze, or any other material that seals the wound and prohibits the flow of air into the pleural cavity. One corner of the dressing is left unsealed to allow accumulated air to escape. The patient should be placed in a semi-Fowler’s position if possible. Once the patient is in an emergency facility, treatment includes chest tube insertion with closed system drainage (Chapter 15).

Tension pneumothorax develops when air enters the pleural space on inspiration but remains trapped there rather than being expelled on expiration. It can occur from trauma, mechanical ventilation, or rib fracture during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The air in the pleural space increases with each breath, and the pressure within the chest builds, which gradually collapses the lung. If unrelieved, this increasing pressure will cause a mediastinal shift, resulting in a decrease in cardiac output and blood pressure. Mediastinal shift means that the structures in the mediastinum—the heart, great vessels, trachea, and esophagus—are all shifted to the unaffected side of the chest. The vena cava can become “kinked” and cause cardiac arrest. In this case, a flutter valve needle or Heimlich valve may be used until a chest tube can be placed to remove the air from the pleural cavity.

Abdominal Trauma

Penetrating abdominal trauma is usually the result of a knife or gunshot wound. At the scene, external wounds with evisceration can be temporarily covered with a piece of nonadhering material such as plastic wrap or aluminum foil. This will keep the protruding intestinal contents moist and relatively free of contamination. After the occlusive covering is applied, a clean folded towel or sheet is placed over it to retain body heat in the protruding organs. No attempt should be made to replace the abdominal organs through the wound. The victim is transported to a medical facility as quickly as possible.

Particularly with gunshot injuries, exit and entrance wounds are anticipated, thus all clothing must be removed by the EMS and/or ED staff and the anterior and posterior body surfaces must be examined. The amount of surface bleeding may be misleading because the path of a bullet is not necessarily linear. Information about the weapon or the attack, such as the length of the knife, caliber of the gun, or position of the shooter, is invaluable because it helps to predict the degree of damage (Hussey, 2010).

Blunt trauma is less dramatic, but can result from improperly worn seat belts, or physical assault. Rapid changes in speed, crushing, or shearing actions result in hemorrhage and damage to internal organs. The survival rate for blunt trauma is 90% to 95% (Hussey, 2010), but the victim must be observed closely for symptoms of shock, and serial abdominal assessments must be performed. A bluish tinge around the umbilicus may indicate abdominal hemorrhage (Cullen’s sign). Ecchymosis or bruising along the flank is a sign of retroperitoneal bleeding (Grey Turner’s sign).

Focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST), peritoneal lavage, or computed tomography may be performed to diagnose intra-abdominal bleeding. Additional diagnostic tests include serial hemoglobin and hematocrit, blood chemistries, and urinalysis. Treatment includes two large-bore intravenous (IV) lines, nasogastric tube, Foley catheter, and type and crossmatch for blood.

Multiple Trauma

The most common cause of multiple trauma is motor vehicle accidents. Among the elderly, falls are the most common cause. Head injury, fractures, and chest and abdominal injuries are anticipated. Airway management is always the first priority (see Focused Assessment on p. 1023). In head trauma, ventilation and oxygenation may be compromised due to decreased level of consciousness and C-spine precautions must be observed when performing airway interventions. Threats to breathing may include injuries such as pneumothorax, rib fractures, or open chest wounds. The multiple trauma patient has high risk for hypovolemic shock. Tension pneumothorax and cardiac tamponade (compression) can also compromise circulation and lead to shock.

Metabolic Emergencies

Insulin Reaction or Severe Hypoglycemia

Brain cells needs a constant supply of glucose. If glucose levels drop, level of consciousness is altered and blood vessels dilate. The classic clinical picture of a patient who has received too much insulin includes altered level of consciousness; cold, clammy skin; and hypotension, dizziness, and tachycardia. Most, but not all, patients experiencing hypoglycemia have diabetes.

Treatment

First obtain a glucose reading, if at all possible; if glucose monitoring equipment is not available, but you suspect hypoglycemia, initiate treatment without delay. If the patient is awake, give him a glass of milk. Glucose tablets or hard candy may also be used. Alteration in level of consciousness often results in impaired swallowing. Attempts to give glucose by mouth could result in aspiration. If a patient has a decreased level of consciousness, IV glucose may need to be given. If an IV line is not in place, intramuscular glucagon can be given by medical personnel or trained family members. Mental status should improve within minutes of receiving glucose. The patient should be given a protein meal, such as a meat sandwich, as soon as he is alert enough to eat. Follow-up care includes teaching about prevention of hypoglycemic episodes, recognition of the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia, and emergency treatment.

Other Metabolic Emergencies

Other metabolic emergencies include thyroid storm, addisonian crisis, and diabetic ketoacidosis. See Chapters 37 and 38.

Injuries Caused by Extreme Heat and Cold

Heatstroke

Heatstroke is the result of a serious disturbance of the heat-regulating center in the brain and can be exertional or nonexertional. Exertional heatstroke tends to occur in young, healthy individuals who engage in prolonged physical activity in a hot environment. The very young, very old, chronic invalids, those on medications such as anticholinergics, or those with weight or alcohol problems are at risk for nonexertional heatstroke (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA], 2009). Normally, the body is able to regulate body temperature even with increased activity or changes in environmental temperatures by increasing perspiration and by using other internal mechanisms. In heatstroke, these mechanisms fail to function properly and the patient’s temperature rises, the skin becomes dry and hot, and there may be convulsions and collapse. Alteration in neurologic function is a finding common to both types of heatstroke. Other symptoms include visual disturbances, dizziness, nausea, and a weak, rapid, irregular pulse. The body temperature may go as high as 108° to 110° F (42.2° to 43.3° C). Untreated heatstroke could result in complications or death related to cerebral edema and hemorrhage, dilation of the heart and rupture of the myocardial fibers, disseminated intravascular coagulation, pulmonary edema, and kidney or liver failure (Brege, 2009).

Prevention

In hot weather or if active in warm weather, take precautions. Drink plenty of fluids that are nonalcoholic, noncaffeinated, and low in sugar content (the wrong fluids can increase fluid loss); do not wait until thirsty to drink fluids. Stay indoors and if air conditioning or adequate cooling is not available in the home, go to a public place with air conditioning (NOAA, 2009).

In the heat, wear lightweight, light-colored, loose-fitting clothing. Limit outdoor activities to morning and evening hours, using sun protection such as wide-brimmed hats, sunglasses, and sunscreen. Try to rest often in shaded areas and limit exertion if possible.

Treatment

A person suffering from heatstroke should be placed in the shade and cooled immediately by sprinkling with water and fanning until EMS arrives. Active cooling measures at the hospital include removal of extra clothing or coverings, wiping the skin with cool wet towels or application of ice packs to the groin and axillae, use of a cooling blanket, iced saline lavage, and infusion of cold fluids. Active cooling measures are discontinued when the rectal temperature reaches 102.2° F (39° C); this prevents rebound hypothermia (Brege, 2009).

Hypothermia

People most at risk for hypothermia are the elderly, very young and thin children, the mentally ill, the homeless, and others unable to alter their ambient environment. Hypothermia is a serious lowering of the total body temperature caused by prolonged exposure to cold. The extremities can withstand lower temperatures (20° to 30° F lower). When the core (central) temperature drops even 2° or 3° F, fatal cardiac dysrhythmias or respiratory failure can occur.

Symptoms of hypothermia range from mild shivering and complaints of feeling cold and loss of coordination to eventual loss of consciousness and a deathlike appearance. In severe hypothermia, the body’s protective mechanisms will drastically slow the metabolic processes and require less than half the normal oxygen. Pulse and respiration are barely detected, reflexes are absent, and the person is unconscious.

Prevention

Prevention of hypothermia includes eating high-energy foods, exercising, wearing layers of clothing, and covering the head. From one half to two thirds of the body’s heat is lost through the head. Hypothermia in elderly individuals can easily be misdiagnosed because the symptoms resemble those of so many diseases to which the elderly and weak are most susceptible. Mild hypothermia (90° to 95° F [32° to 35° C] body temperature) is usually tolerated fairly well. Moderate hypothermia (84° to 90° F [29° to 32° C] body temperature) results in a mortality rate of about 21%. Severe hypothermia (core temperature below 82° F [28° C]) has an even higher mortality rate.

Most oral clinical thermometers used in hospitals and clinics do not register temperatures below 94° F (34.5° C). In the ED, rectal, bladder, or esophageal probes will be used to monitor true core temperature throughout the warming process.