CHAPTER 4 One in five children and adolescents of any age in the United States (20%) suffers from a major psychiatric disorder that causes significant impairments at home, school, and with peers (Black and Andreasen, 2011). If left untreated, all areas of the child or adolescent’s life will be tragically impeded, leaving young people socially isolated, stigmatized, and unable to live up to their potential and/or contribute to society. The risk factors for mental disorders in childhood or adolescence are many. Genetic, biochemical, prenatal, and postnatal influences; individual temperament; personal psychosocial development, and personal resiliency are all potential risk factors. The vulnerability to risk factors is the result of a complex interaction among many factors (e.g., constitutional endowment, trauma, disease, and interpersonal experiences). Vulnerability changes over time as children/adolescents grow and the emotional and physical environment changes. As children and adolescents mature, they develop competencies that enable them to communicate, remember, test reality, solve problems, make decisions, control drives and impulses, modulate affect, tolerate frustration, delay gratification, adjust to change, establish satisfying interpersonal relationships, and develop healthy self-concepts. These competencies reduce the risk for developing emotional, mental, or health problems. Although it is true that the majority of mental suffering experienced by children and adolescents is related to situational stresses that respond to psychological treatment, it is also true that many mental illnesses begin in childhood. The following disorders, most commonly seen in children and adolescents, are discussed in this chapter: (1) attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, (2) disruptive behaviors including conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and (3) autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Anxiety disorders are covered in Chapter 5, and depression and bipolar disorders are addressed in Chapters 7 and 8, respectively. Currently accepted psychopharmacological agents used in the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents are included in Table 4-2. The observation/interaction part of a mental health assessment begins with a semi-structured interview in which the child or adolescent is asked about life at home with parents and siblings and life at school with teachers and peers. Because the interview is not rigidly structured, children are free to describe their current problems and give information about their own developmental history. Play activities, such as games, drawing, puppets, and free play, are used for younger children who cannot respond to a direct approach. An important part of the first interview is observing interactions among the child, caregiver, and siblings (when possible). Nurses working with children and adolescents need to have a good grasp of growth and development. A chart comparing and contrasting the psychosexual stages of development according to Erickson, Freud, and Sullivan is found in Appendix C-1. The developmental assessment (Appendix C-2) provides information about the child’s current maturational level. This can help the nurse identify current lags or deficits. The Mental Status Assessment (Appendix C-3) provides information about the child’s/adolescent’s current mental state. The developmental and mental status assessments have many areas in common, and for this reason any observation and interaction will provide data for both assessments. Families should always be involved in therapy and are given support in parenting skills designed to help them provide nurturance and set consistent limits. They are the key players in carrying out the treatment plan, using behavior modification techniques at home, monitoring the medication’s effects, collaborating with the teacher to foster academic success, and making a home environment that promotes the achievement of normal developmental tasks. When families are abusive, drug dependent, or highly disorganized, the child may benefit from out-of-home placement. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) accounts for 3% to 10% of the cases of mental disorders in children or adolescents, and affects up to 8% to 9% of school-age children (Lehne, 2013). Characteristic symptoms of ADHD are inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. According to Preston and colleagues (2010), most young people with ADHD will outgrow their motor restlessness/hyperactivity, but will retain the core symptoms (impulsivity, impaired attention, and lack of intrinsic motivation) throughout adolescence and into adulthood. ADHD is difficult to diagnose before 4 years of age. ADHD often manifests as excessive gross-motor activity that becomes less pronounced as the child matures. The disorder is most often identified when the child has difficulty adjusting to elementary school—a time when children are expected to control behavior, follow rules, and stay on task in an age-appropriate manner. In any case, symptoms of ADHD must be present prior to adolescence in order to be given this diagnosis. The attention problems and hyperactivity contribute to low tolerance for frustration, temper outbursts, labile moods, poor academic performance, rejection by peers, low self-esteem, and disorganization. In adolescence, disorganization is evidenced by cluttered bedrooms, disorganized lockers, and messy notebooks (Preston et al., 2010). An increased incidence of depression—up to 20%—is diagnosed in children with ADHD. Nocturnal or daytime enuresis, disruptive behavior disorders, and Tourette’s disorder have been associated with ADHD. Symptoms of ADHD include the following: (CDC, 2009: APA, 2013) • Has difficulty paying attention during tasks or play • Does not seem to listen when spoken to, mind seems to wander • Does not, follow through, or finish tasks • Does not pay attention to details, and makes careless mistakes • Is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort • Is easily distracted, loses things, and is forgetful in daily activities • Has difficulty processing information • Struggles to follow instructions • Has difficulty organizing tasks and activities Hyperactivity • Fidgets; is unable to sit still or stay seated in school • Unable to play or engage in leisure activities quietly • Runs and climbs excessively in inappropriate situations • Acts as if “driven by a motor”; constantly “on the go” • Talks excessively • Acts without thinking • Finds it difficult to resist temptations or opportunities (e.g., a child may grab toys off the store shelf or play with dangerous objects; adults may commit to a relationship after only a brief acquaintance, or take a job or enter into a business arrangement without due diligence) • Has trouble sitting still during meals, school, movies and may leave seat in situations when expected to remain seated Impulsivity • Blurts out answer before question is completed • Has difficulty waiting his or her turn • Interrupts, intrudes in others’ conversations and games • Is very impatient There are a number of influences that are thought to contribute to the development or cause ADHD; however, as yet, there is no known definitive cause. Some theories involve low birth weight, history of child abuse or neglect, exposure to toxins or alcohol in utero, or specific genetic and physiological traits. Multiple neuroimaging studies find that structural and functional abnormalities present in many areas of the brain are involved in regulating attention, impulsive behavior, and motor activity (Lehne 2013). The interventions for ADHD are behavior modification and pharmacological agents for the inattention and the hyperactive or impulsive behaviors, special education programs for the academic difficulties, and psychotherapy and play therapy for the emotional problems that develop as a result of the disorder. Psychostimulants are used to treat ADHD, as a sluggish frontal lobe is thought to be causative of the disorder. Methylphenidate (Ritalin) is the most widely used stimulant because of its safety and simplicity of use. It is available orally and as a transdermal patch (Daytrana). Concerta is an extended-release form of Ritalin that allows once-daily dosing. Adderall is another psychostimulant (containing dextroamphetamine and amphetamine) that also calms the patient, and it is available in extended-release form. Approximately 70% to 90% of people with ADHD do fairly well when prescribed stimulants; however, because of side effects or nonresponse, up to 50% of patients may discontinue psychostimulants (Strange, 2008). Research on alternative drugs is ongoing because children who do not respond to stimulants (almost 30% of children with ADHD) are often categorized as an “inattentive type” of ADHD that is thought by some to be a totally different kind of neurological disorder (Preston et al., 2010). Two more recently approved U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) drugs that are α2-agonist nonstimulants seem to be benefiting patients. Clonidine hydrochloride and guanfacine hydrochloride may be used as an alternative or as an adjunct with stimulants. Guanfacine seems to decrease symptoms of aggression and insomnia related to psychostimulant use, and clonidine has shown significantly improved symptoms of ADHD in children 6 to 17 years of age when used in conjunction with psychostimulants. Tricyclic antidepressants or bupropion hydrochloride (i.e., Wellbutrin) may also be used (Black & Andreasen, 2011). Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) is a persistent pattern of negativity, disobedience, defiance, and hostility directed toward authority figures (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2012). Almost all children at some time exhibit symptoms characteristic of ODD, such as having temper tantrums, being argumentative, or refusing to obey or do chores. However, to be diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder, these behaviors need to happen “more persistently and more frequently” than what would be considered within the range of normal behaviors. Children with ODD exhibit persistent angry/irritable mood stubbornness, argumentative/defiant behaviors and/or vindictive behaviors. This behavior is evident at home but may not be present elsewhere. These children and adolescents do not see themselves as defiant; instead, they feel they are responding to unreasonable demands or situations. According to the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2011), WebMed (2009), and APA (2013), symptoms may include: • Frequent temper tantrums, often loses temper • Easily annoyed • Frequent anger and resentment Argumentative/Defiant Behavior • Excessive arguing with adults • Annoys others deliberately • Blames others for his or her mistakes or misbehavior • Defies or refuses to comply with requests from authority figures or with roles Vindictiveness • Spiteful attitude and revenge-seeking behaviors when upset Conduct disorder is a serious behavioral and emotional disorder characterized by a persistent pattern of behavior that typically begins during childhood and adolescence in which the rights of others and societal rules are violated and societal norms and rules are violated The child or adolescent act out these patterns of behaviors in all settings. Conduct disorder is considered a forerunner of antisocial/asocial personality disorder, since children with conduct disorder share the same symptomatology (Mental Health America, 2012; WebMed, 2009; APA, 2013). • Is physically cruel to people and animals • Destructive behavior (e.g., intentional destruction such as arson, vandalism) • Uses weapons that can cause considerable harm to others • Deceitfulness (e.g., conning or manipulating others, lying) to obtain goods or avoid responsibilities • Serious rule violations (e.g., running away from home, truancy before the age of 13, sexual activity at a very young age) • Stays out late at night despite parental prohibitions beginning before the age of 13 • Specify if: b. Callous/lack of empathy c. Unconcerned about performance in school, work, or other important activities d. Does not express feelings or show emotions, affect may describe as shallow, insincere, or superficial Childhood-onset conduct disorder can be in evidence as early as 2 years of age (irritable temperament, poor compliance, inattentiveness, impulsivity), which in later years can lead to conduct disturbance. As these children reach elementary school age, aggressive tendencies with adults and peers continue. They do not follow social mores and lack the ability to resolve psychosocial issues (Bernstein et al., 2011). These children are physically aggressive, have poor peer relationships with little concern for others, and lack feelings of guilt or remorse. To make matters worse, they misperceive the intentions of others as being hostile and believe their aggressive responses are justified. Although they try to project a tough image, they have low self-esteem and low tolerance for frustration, show irritability, and have temper outbursts. As time progresses, behavior includes intense anger and aggression as an emotional overreaction to perceived slights, always blaming others for their own actions, and noncompliance with demands (Bernstein et al., 2011). Early onset often indicates a poorer outcome. Adolescent-onset conduct disorder results in less aggressive behaviors and more normal peer relationships. These individuals are likely to have a better outcome. These pre-adults tend to act out their misconduct with their peer group (e.g., truancy, early-onset sexual behaviors, drinking, substance abuse, and risk-taking behaviors). Males are more apt to fight, steal, vandalize, and have school discipline problems, whereas girls lie, run away, and engage in prostitution. Conduct disorders lead to academic failure, failure to graduate, juvenile delinquency, and the need for the juvenile court system to assume responsibility for youths who cannot be managed by their parents. Unfortunately, interaction with other deviant peers often worsens the behaviors (Bernstein et al., 2011). Other psychiatric disorders frequently coexist with conduct disorders such as anxiety, mood disorders, learning disorders, and ADHD. Overall interventions for oppositional defiant and conduct disorders focus on correcting the child’s or adolescent’s faulty beliefs about self and strengthening his or her ability to control impulses, which involves developing more mature and adaptive coping mechanisms. This is a gradual process not amenable to brief treatment. Conduct disorders may require inpatient hospitalization for crisis intervention, evaluation, and treatment planning, as well as transfer to therapeutic foster care or long-term residential treatment. Youths with oppositional defiant disorder are generally treated as outpatients, with much of the focus on parenting issues. Multisystemic therapy is an evidence-based model that emphasizes the home environment and the empowerment of families through several hours of treatment each week. To control aggressive behaviors, a wide variety of pharmacological agents have been used, including antipsychotics, lithium carbonate, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and β-adrenergic blockers. Cognitive behavioral therapy is used to change the pattern of misconduct by fostering the development of internal controls, both cognitive and emotional. Important components of the treatment program include learning problem-solving techniques, conflict resolution, and empathy. 2. Assess the quality of the relationship between the child and parent/caregiver for evidence of bonding, anxiety, tension, and difficulty of fit between the parents’ and child’s temperament, which can contribute to the development of disruptive behaviors. 3. Assess the parent/caregiver’s understanding of growth and development, parenting skills, and handling of problematic behaviors, because lack of knowledge contributes to the development of these problems. 4. Assess for difficulty in making friends and performing in school. Academic failures and poor peer relationships lead to low self-esteem, depression, and further acting out. 5. Assess for problems with enuresis and encopresis. 1. Identify issues that result in power struggles, when they began, and how they are handled. 2. Assess the severity of the defiant behavior and its impact on the child’s life at home, at school, and with peers. 3. How does the child respond to limits? Being told “no”? Having to wait, share, or end a favorite activity? (protests, tantrums) 2. Assess the child’s levels of anxiety, aggression, anger, and hostility toward others and the ability to control destructive impulses. 3. Assess the child’s moral development for the ability to understand the impact of the hurtful behavior on others, empathize with others, and feel remorse 4. Assess cognitive, psychosocial, and moral development for lags or deficits, because immature developmental competencies result in disruptive behaviors. Children and adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Conduct Disorder, and Oppositional Defiant Disorder all display disruptive behaviors that are impulsive, angry/aggressive, and often dangerous (Risk for Violence). These children and adolescents are often in conflict with parents and authority figures, refuse to comply with requests, do not follow age-appropriate social norms, or have inappropriate ways of getting needs met (Defensive Coping). When their behavior is disruptive or aggressive and hostile, they have difficulty making or keeping friends (Impaired Social Interaction). Their problematic behaviors can impair learning and result in academic failure. Interpersonal and academic problems lead to high levels of anxiety, low self-esteem, and blaming others for one’s troubles (Chronic Low Self-Esteem). Parents/caregivers have difficulty handling disruptive behaviors and being effective parents, so their participation in the therapeutic program is essential (Impaired Parenting). Help the child reach his or her full potential by fostering developmental competencies and coping skills: 2. Provide immediate nonthreatening feedback for unacceptable behaviors. 3. Increase the child’s or adolescent’s ability to trust and use interpersonal skills to maintain satisfying relationships with adults and peers. 4. Provide immediate positive feedback for acceptable behaviors. 5. Increase the child’s or adolescent’s ability to control impulses, tolerate frustration, and modulate the expression of affect. 6. Foster the child’s or adolescent’s identification with positive role models so that positive attitudes and moral values can develop that enable the youth to experience feelings of empathy, remorse, shame, and pride. 7. Use role-play to help the child or adolescent respond in a more acceptable manner when feeling frustrated or aggressive. 8. Foster the development of a realistic self-identity and self-esteem based on achievements and the formation of realistic goals. 9. Provide support, education, and guidance for parents or caregivers. • Control aggressive, impulsive behaviors • Demonstrate respect for the rights of others Child/adolescent will: Child/adolescent will: • Respond to limits on aggressive and cruel behaviors within 2 to 4 weeks • Identify at least three situations that trigger violent behaviors within 1 to 2 months • Channel aggression into constructive activities and appropriate competitive games within 2 to 4 weeks • State the effects of his or her behavior on others within 2 to 4 weeks • Demonstrate the ability to control aggressive impulses and delay gratification within 2 to 8 weeks

Selected Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence

OVERVIEW

Initial Assessment

Assessment Tools

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Disruptive Behavior Disorders (Oppositional Defiant Disorder [ODD])

ASSESSMENT

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

DIAGNOSIS*

Behavioral and Psychotherapeutic Interventions for ADHD

DISRUPTIVE BEHAVIORS

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

CONDUCT DISORDER

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Behavioral and Psychopharmacological Interventions for Oppositional Defiant and Conduct Disorders

ASSESSMENT

Specific Assessment Guidelines

Assessment Guidelines

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

Conduct Disorder

Discussion of Potential Nursing Diagnoses

Overall Guidelines for Nursing Interventions

Attention Deficit, Conduct Disorder, and Oppositional Defiant Disorder

Selected Nursing Diagnoses and Nursing Care Plans

Risk Factors (Risk-Related Behaviors)

Impaired neurological development or dysfunction

Impaired neurological development or dysfunction

Cognitive impairment (e.g., learning disabilities, attention deficit disorder, decreased intellectual functioning)

Cognitive impairment (e.g., learning disabilities, attention deficit disorder, decreased intellectual functioning)

History of childhood abuse or witnessing family violence

History of childhood abuse or witnessing family violence

History of violent antisocial behavior (e.g., stealing, insistent borrowing, insistent demands for privileges, insistent interruptions of meetings, refusal to eat, refers and take medication, ignoring instructions)

History of violent antisocial behavior (e.g., stealing, insistent borrowing, insistent demands for privileges, insistent interruptions of meetings, refusal to eat, refers and take medication, ignoring instructions)

History of other related violence (e.g., hitting, kicking, scratching, throwing objects at someone, biting someone, attempted sexual assault, molestation, urinating/defecating on a person)

History of other related violence (e.g., hitting, kicking, scratching, throwing objects at someone, biting someone, attempted sexual assault, molestation, urinating/defecating on a person)

Physical cruelty to people and/or animals

Physical cruelty to people and/or animals

History of threats of violence (e.g. verbal threats, against property, verbal threats against person, social threats, sexual threads, threatening communications)

History of threats of violence (e.g. verbal threats, against property, verbal threats against person, social threats, sexual threads, threatening communications)

Psychotic symptomatology (e.g., hallucinations, paranoid delusions, illogical thought process)

Psychotic symptomatology (e.g., hallucinations, paranoid delusions, illogical thought process)

Emotional problems (e.g., hopelessness, despair, increased anxiety, panic, anger, hostility)

Emotional problems (e.g., hopelessness, despair, increased anxiety, panic, anger, hostility)

History of substance abuse; pathological intoxication

History of substance abuse; pathological intoxication

Outcome Criteria

Long-Term Goals

Short-Term Goals

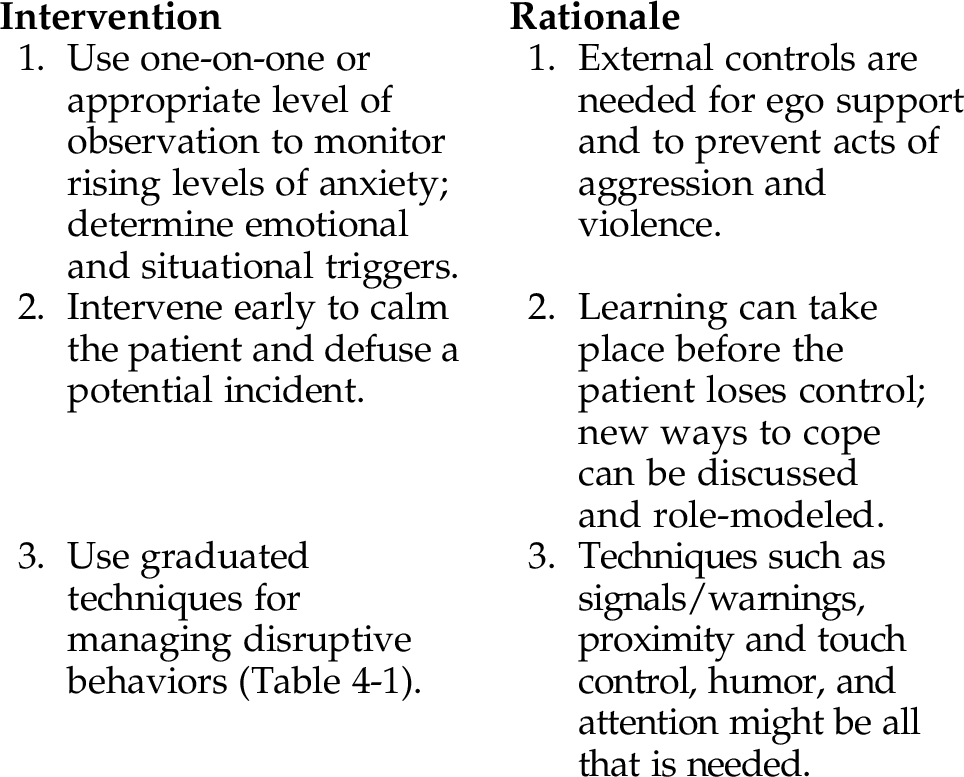

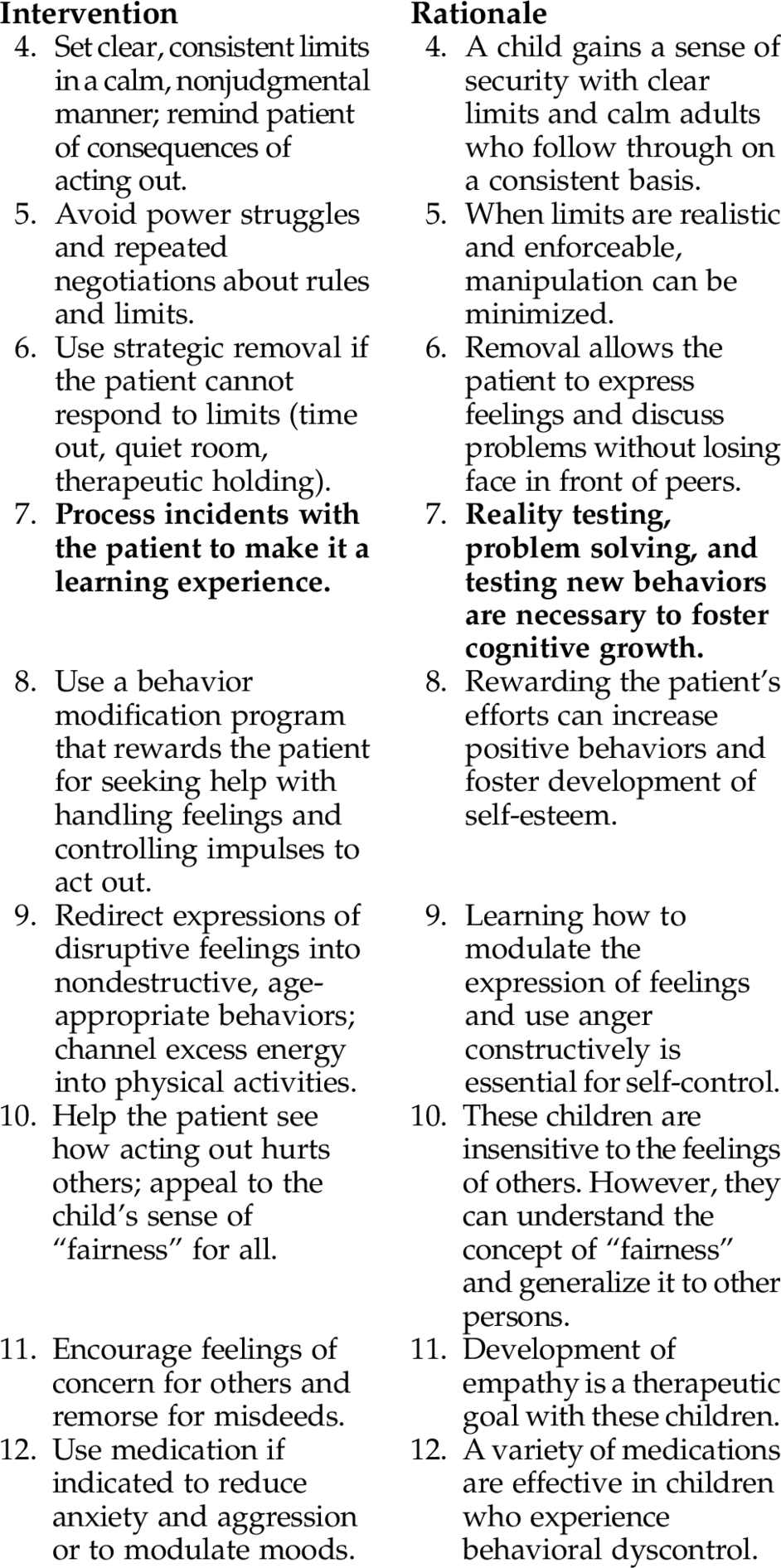

INTERVENTIONS AND RATIONALES

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree