Health Promotion and Risk Reduction

Bridgette Crotwell Pullis and Mary A. Nies

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

2. Discuss definitions of health.

3. Demonstrate an understanding of the difference between health promotion and health protection.

4. Define risk.

5. Discuss the relationship of risk to health and health promotion activities.

6. Demonstrate an understanding of stratification of risk factors by age, race, and gender.

7. Discuss the influence of various factors on health.

8. List health behaviors for health promotion and disease prevention.

9. Relate the clinical implications of health promotion activities.

Key terms

determinants of health

health

health promotion

health protection

portion distortion

risk

risk communication

risk reduction

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

Health promotion and community health nursing

Since its inception, nursing has focused on helping individuals, groups, and communities maintain and protect their health. Florence Nightingale and other nursing pioneers recognized the importance of nutrition, rest, and hygiene in maximizing and protecting one’s state of health. Though people are responsible for their health and medical care, they often seek advice from nurses in the community regarding health promotion and to help them make sense of the many, and often competing, recommendations that appear daily on TV, online, in newspapers, and in magazines.

Read the following Clinical Example about Jamie R.:

Green and Kreuter (1991) define health promotion as “any combination of health education and related organizational, economic, and environmental supports for behavior of individuals, groups, or communities conducive to health” (p. 2). Parse (1990) states that health promotion is that which is motivated by the desire to increase well-being and to reach the best possible health potential. Jamie exemplifies this motivation to stay in her best health, at least at first glance. Let’s look further into Jamie’s health history.

When it comes to health practices, Jamie is a study in contradictions. Jamie’s father had a myocardial infarction (MI) at the age of 48 years and died of an MI at the age of 50 years. Many of Jamie’s paternal relatives have died of heart disease. Jamie’s mother and one maternal aunt each had breast cancer diagnosed in their early 50s. Though she has an annual physical by her family doctor and monitors her blood cholesterol and triglycerides, Jamie has never been screened for cardiac disease. Jamie takes the flu vaccine every year but has not had a tetanus-diphtheria vaccine booster in 14 years; though she sees her gynecologist yearly, she has had only one mammogram, 3 years ago.

In skipping annual mammograms and in not pursuing cardiac screening despite her high risk, Jamie is neglecting an important step in maintaining her health—health protection. Health protection is those behaviors in which one engages with the specific intent to prevent disease, to detect disease in the early stages, or to maximize health within the constraints of disease (Parse, 1990). Immunizations and cervical cancer screening are examples of health protection activities.

In discussing health promotion, it is helpful to define what is meant by health. An early definition defines health as “being sound in body, mind, and spirit: freedom from physical disease or pain” (Merriam-Webster, 2009). As health promotion has become an important strategy to improve health, the way health is defined has shifted from a focus on the curative model to a focus on multidimensional aspects such as the social, cultural, and environmental facets of life and health (Benson, 1996). The well-known definition by the World Health Organization (WHO) states that health is “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease” (WHO, 2009). WHO also states that health is the extent to which an individual or group is able to realize aspirations, to satisfy needs, and to change or to cope with the environment. In this aspect, health is viewed not only as an important goal but as a resource for living (WHO, 1986).

Healthy people 2020

Healthy People 2020 is the health promotion initiative for the nation. Developed through a consortium and managed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Healthy People 2020 “challenges individuals, communities, and professionals, indeed all of us to take specific steps to ensure that good health, as well as long life, are enjoyed by all” (USDHHS, 2009).

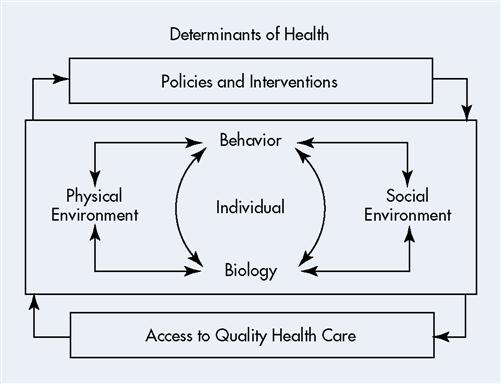

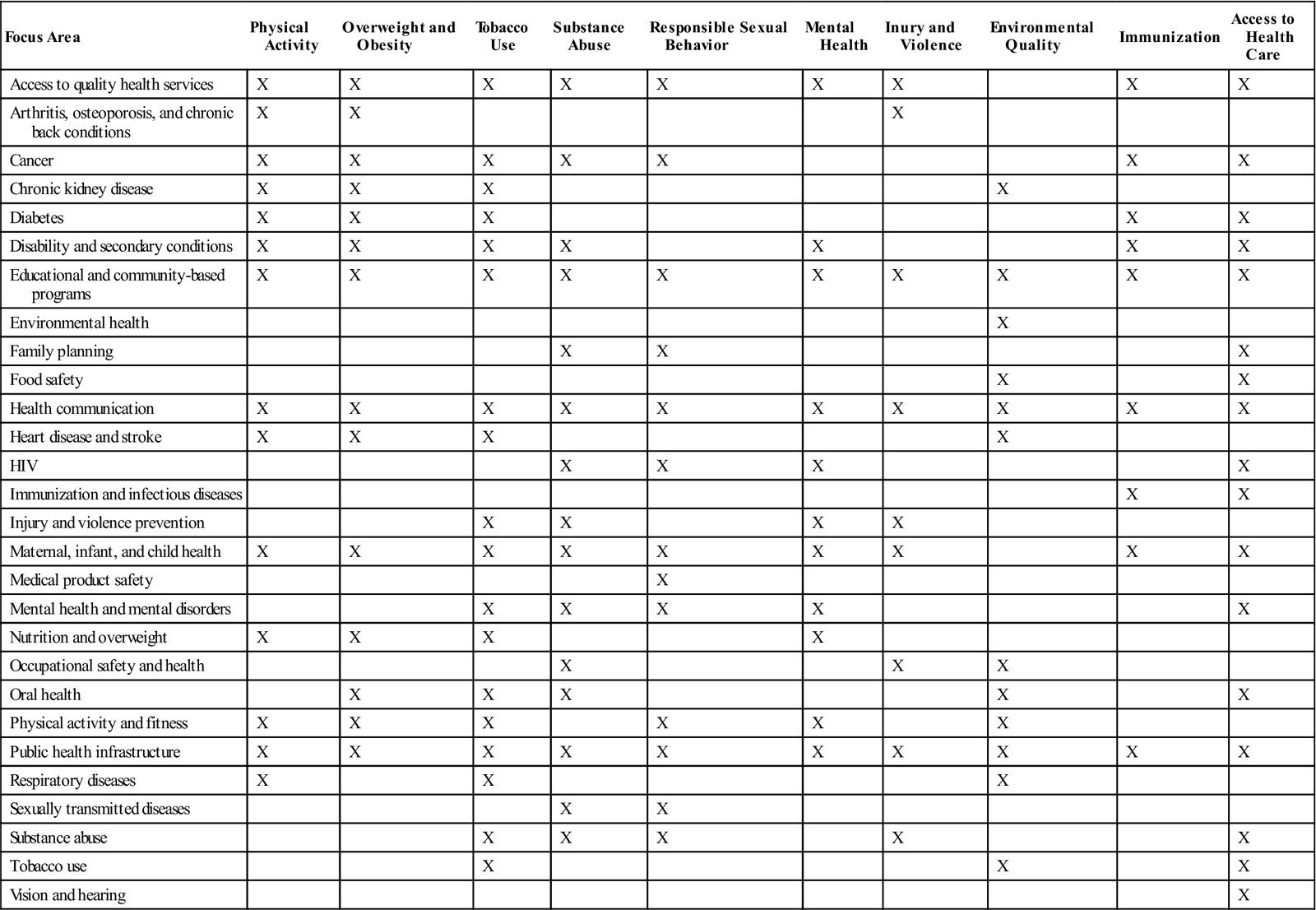

The broad goals of Healthy People 2020 are to attain high quality, longer lives free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death; achieve high equity, eliminate disparities and improve the health of all groups; create social and physical environments that promote good health for all; and promote quality of life, healthy development, and healthy behaviors across all life stages. Objectives toward achieving these goals are organized into 38 topic areas with corresponding priorities for action for each objective. Leading health indicators, or determinants of health, in each topic area help track progress toward meeting the goals of Healthy People 2020. A list of leading health indicators common across most of the topic areas is found in Table 4-1. Figure 4-1 illustrates the relationships among the determinants of health. The home page for Healthy People 2020 can be accessed at www.healthypeople.gov/Default.htm.

TABLE 4-1

| Focus Area | Physical Activity | Overweight and Obesity | Tobacco Use | Substance Abuse | Responsible Sexual Behavior | Mental Health | Inury and Violence | Environmental Quality | Immunization | Access to Health Care |

| Access to quality health services | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Arthritis, osteoporosis, and chronic back conditions | X | X | X | |||||||

| Cancer | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Diabetes | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Disability and secondary conditions | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Educational and community-based programs | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Environmental health | X | |||||||||

| Family planning | X | X | X | |||||||

| Food safety | X | X | ||||||||

| Health communication | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Heart disease and stroke | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| HIV | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Immunization and infectious diseases | X | X | ||||||||

| Injury and violence prevention | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Maternal, infant, and child health | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Medical product safety | X | |||||||||

| Mental health and mental disorders | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Nutrition and overweight | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Occupational safety and health | X | X | X | |||||||

| Oral health | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Physical activity and fitness | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Public health infrastructure | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Respiratory diseases | X | X | X | |||||||

| Sexually transmitted diseases | X | X | ||||||||

| Substance abuse | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Tobacco use | X | X | X | |||||||

| Vision and hearing | X |

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus.

From Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services: Leading health indicators touch everyone, Healthy People 2010, 2009 (website): www.healthypeople.gov/LHI/Touch_fact.htm. Accessed March 18, 2009.

Determinants of health

Biology is an individual’s genetic makeup, family history, and any physical and mental health problems developed in the course of life. Aging, diet, physical activity, smoking, stress, alcohol or drug abuse, injury, violence, or a toxic or infectious agent may produce illness or disability that changes an individual’s biology.

Behaviors are the individual’s responses to internal stimuli and external conditions. Behaviors interact with biology in a common relationship as one may influence the other. If a person chooses behaviors such as alcohol abuse or smoking, his or her biology may be changed as a result (e.g., liver cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]). On the other hand, if an individual has a history of colon cancer in his or her family, the individual may choose to have regular screenings, thereby preventing advanced cancer and possibly death, and changing his or her biology for the better. One’s biology may impact behavior; if a person has hypertension or diabetes, he or she may choose to begin an exercise regimen and to eat more healthfully.

Social environment includes interactions and relationships with family, friends, co-workers, and others in the community. Social institutions, such as law enforcement, faith communities, schools, and government agencies, are also part

of the social environment, as well as housing, safety, public transportation, and availability of resources. The social environment has a great impact on the health of individuals, groups, and communities, yet it is complex in nature because of differing cultures and practices.

Physical environment is that which is experienced with the senses; that is smelled, seen, touched, heard, and tasted. The physical environment can impact health negatively or positively. If there are toxic or infectious substances in the environment, this is certainly a negative influence on health. If the environment is clean with areas to recreate and play, this is a good influence on health.

Policies and interventions can have a profound effect on the health of individuals, groups, and communities. Positive effects such as policies against smoking in public places, seatbelt and child restraint laws, litter ordinances, and enhanced health care promote health. Policies are implemented at local, state, and national levels by many agencies such as transportation, health and human services, veterans’ affairs, housing, and justice departments.

Access to quality health care: expansion of health care access is essential to decrease health disparities and to increase the quality of life and the quantity of years of healthy life (USDHHS, 2001).

Theories in health promotion

Health promotion activities are broad in scope and in setting. Community health nurses and their clients engage in health promotion activities in workplace settings, schools, clinics, and communities. The theories that are used most in health promotion are very diverse to accommodate the variety of settings, clients, and activities in community health. A working knowledge of theory is important in understanding why people act as they do and why they may or may not follow advice given to them by medical professionals, and in helping clients progress from knowledge to behavior change. Some of the most frequently used health promotion theories and models are discussed below.

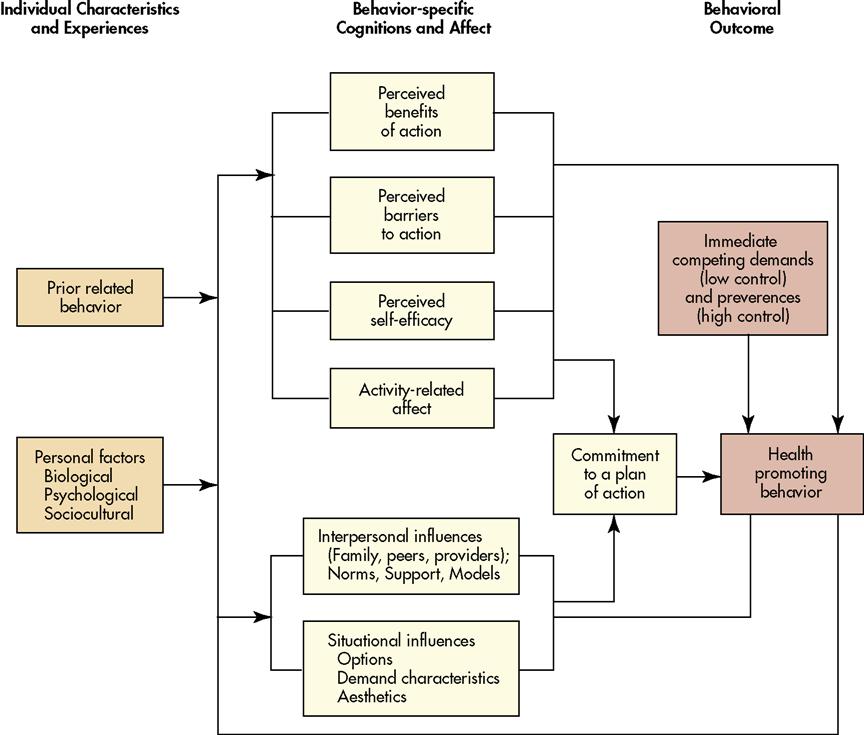

Pender’s Health Promotion Model

Developed in the 1980s and revised in 1996, Pender’s Health Promotion Model (HPM) explores the myriad biopsychosocial factors that influence individuals to pursue health promotion activities. The constructs or variables of the HPM are listed and described in Table 4-2. The HPM depicts the complex multidimensional factors with which people interact as they work to achieve optimum health. This model contains seven variables related to health behaviors, as well as individual characteristics that may influence a behavioral outcome.

TABLE 4-2

Pender’s Health Promotion Model

| Individual Characteristics and Experiences | Each Person’s Unique Characteristics and Experiences Affect their Actions. Their Effect Depends on the Behavior in Question. |

| Prior related behavior | Prior behaviors influence subsequent behavior through perceived self-efficacy, benefits, barriers, and affects related to that activity. Habit is also a strong indicator of future behavior. |

| Personal factors | Personal factors that may influence behavior are biologic factors such as age, BMI, strength, and agility; psychological factors include self-esteem, self-motivation, and perceived health status; sociocultural factors include race, ethnicity, acculturation, education, and socioeconomic status. |

| Behavior specific cognitions and affect | In the HPM, these variables are considered to be very significant in behavior motivation. They are a “core” for intervention because they may be modified through nursing actions. Assessment of the effectiveness of interventions is accomplished by measuring the change in these variables. |

| Perceived benefits of action | The perceived benefits of a behavior are strong motivators of that behavior. These motivate behavior through intrinsic and extrinsic benefits. Intrinsic benefits include increased energy or decreased appetite. Extrinsic benefits include social rewards such as compliments, or monetary rewards. |

| Perceived barriers to action | Barriers are perceived unavailability, inconvenience, expense, difficulty or time regarding health behaviors. |

| Perceived self-efficacy | Self-efficacy is one’s belief that he is capable of carrying out a health behavior. If one has high self-efficacy regarding a behavior, one is more likely to engage in that behavior than if one has low self-efficacy. |

| Activity-related affect | The feelings associated with a behavior will likely affect whether an individual will repeat or maintain the behavior. |

| Interpersonal influences | In the HPM, these are feelings, thoughts, regarding the beliefs or attitudes of others. Primary influences are family, peers, and health care providers. |

| Situational influences | These are perceived options available, demand characteristics, and the aesthetic features of the environment where the behavior will take place. For example, a lovely day will increase the probability of one taking a walk; the fire code will prevent one from smoking indoors. |

| Commitment to a plan of action | Pender states that “commitment to a plan of action initiates a behavioral event” (Pender et al., 2006, p. 56). This commitment will compel one into the behavior until completed unless a competing demand or preference intervenes. |

| Immediate competing demands and preferences | These are alternative behaviors that one considers as possible optional behaviors immediately prior to engaging in the intended, planned behavior. One has little control over competing demands, but one has great control over competing preferences. |

| Health-promoting behavior | This is the goal or outcome of the HPM. The aim of health-promoting behavior is the attainment of positive health outcomes. |

From Pender N, Murdaugh CL, Parsons MA: Health promotion in nursing practice, 5th ed, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2006, Pearson.

Pender’s model does not include threat as a motivator, as threat may not be a motivating factor for clients in all age groups (Pender et al., 2006). The Health Promotion Model is depicted in Figure 4-2.

Relating the Health Promotion Model for Jamie R. in the Clinical Example on page 51, the experience of having relatives who died of heart disease and cancer has probably increased her desire to engage in healthful behavior. Similarly, her busy schedule and lack of communication with her doctor may be reflected in her lack of desire to have screening or immunizations. Jamie has a habit of engaging in exercise and a high self-efficacy related to her success with exercise in the past. Jamie feels better after exercise, and she receives positive comments from significant others regarding her appearance, also increasing her motivation to exercise. Jamie works out in a lovely gym and is very committed to her workout routine. Jamie has found that by working out first thing in the morning, the competing demands that may keep her from exercising are minimized.

The Health Belief Model

Initially proposed in 1958, the Health Belief Model (HBM) provides the basis for much of the practice of health education and health promotion today. The Health Belief Model was developed by a group of social psychologists to explain why the public failed to participate in screening for tuberculosis (Hochbaum, 1958). Hochbaum and his associates had the same questions that perplex many health professionals today: Why do people who may have a disease reject health screening? Why do individuals participate in screening if it may lead to the diagnosis of disease? Through their work, this group found that information alone is rarely enough to motivate one to act. Individuals must know what to do and how to do it before they can take action. Also, the information must be related in some way to the individual’s needs. One of the most widely used conceptual frameworks in health behavior, the Health Belief Model has been used to explain behavior change and maintenance of behavior change and to guide health promotion interventions (Janz, Champion, and Stretcher, 2002).

The Health Belief Model has several constructs: perceived seriousness, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits of treatment, perceived barriers to treatment, cues to action, and self-efficacy. These components are found in Table 4-3. All of these constructs relate to the client’s perception. How does the client perceive the seriousness of the condition? His susceptibility to the condition? The benefits of prevention or treatment? The barriers to prevention or treatment? The HBM is depicted in Figure 4-3 (McEwen and Pullis, 2009).

TABLE 4-3

Key Concepts and Definitions of the Health Belief Model

| Concept | Definition |

| Perceived susceptibility | One’s belief regarding the chance of getting a given condition |

| Perceived severity | One’s belief regarding the seriousness of a given condition |

| Perceived benefits | One’s belief in the ability of an advised action to reduce the health risk or seriousness of a given condition |

| Perceived barriers | One’s belief regarding the tangible and psychological costs of an advised action |

| Cues to action | Strategies or conditions in one’s environment that activate readiness to take action |

| Self-efficacy | One’s confidence in one’s ability to take action to reduce health risks |

From Janz, JK, Champion, VL, & Stretcher, VJ: The health belief model. In Glanz K, Rimer, BK, Lewis, FM editors: Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice, San Francisco, 2002. Jossey-Bass.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree