Pulmonary fibrosis (PF) is a pathologic term for excessive connective tissue in the lungs that hampers lung recoil and lung deflation during expiration. The disorder is more commonly referred to as interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, fibrosing alveolitis, interstitial pneumonitis, and Hamman-Rich syndrome, although it has many more names (Table 39-1).

| *Other than radiation and chemotherapy. | |

| Name | Examples of Causes* |

|---|---|

| Acute interstitial pneumonitis | Polymyositis, dermatomyositis, psoriasis |

| Chronic diffuse fibrosing pneumonitis | Albinism, SARS, congenital misalignment lung vessels |

| Chronic diffuse sclerosing pneumonitis | Hemangioma |

| Chronic interstitial pneumonia | MPO-ANCA vasculitis, smoking, mesalamine drug use, heroin use, coal worker, EBV, acute lung injury, traction bronchiectasis, plaster worker, nontuberculosis Mycobacterium bronchiolitis (hot tub lung) |

| Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis | HTLV-1 virus, systemic sclerosis, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, metal exposure, hepatitis C virus |

| Diffuse idiopathic interstitial fibrosis | Sarcoidosis, viral infection |

| Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | Bone marrow dysfunction, ARDS, systemic sclerosis, bronchiolitis obliterans |

| Diffuse infiltrative pulmonary disease | Sarcoidosis, autoimmune disease |

| Desquamative interstitial pneumonitis | Dermatomyositis, ABCA3 mutation, smoking, asbestosis |

| Familial pulmonary fibrosis | Familial idiopathic fibrosis |

| Fibrosing alveolitis | Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Jo-1 autoimmune disease, EBV, atrial myxoma, d-penicillamine therapy, systemic sclerosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, nickel dust exposure, zinc oxide inhalation, scleroderma |

| Hamman-Rich disease or syndrome | Dermatomyositis, polymyositis, ARDS, pseudoinfluenza, goldsmith work |

| Honeycomb lung | Lung cancer, connective tissue disease |

| Honey lung | Lung cancer, connective tissue disease |

| Idiopathic fibrosing alveolitis | Connective tissue disease, systemic sclerosis, pulmonary arterial hypertension, sarcoidosis, lung cancer |

| Idiopathic interstitial fibrosis of lung syndrome | Polymyositis, dermatomyositis, smoking |

| Interstitial pneumonitis | HIV mismatch, post BMT, CMV infection, sirolimus medication, smoking, ABCA-3 mutation, polymyositis, dermatomyositis |

| Interstitial pulmonary fibrosis | Systemic sclerosis, asbestosis, Jo-1 autoimmune disease, chronic paraquat intoxication, ammonia gas inhalation, atrial myxoma, ARDS |

| Shrinking lung | SLE, traction bronchiectasis, autoimmune diseases, systemic sclerosis, Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Stiff lung | Atrial-septal defect |

| Usual interstitial pneumonitis (UIP) | Smoking, surfactant protein C mutation, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, Erdheim-Chester disease, varicella pneumonia, dermatomyositis, polymyositis |

Although no clear mechanisms have been validated to explain pulmonary fibrosis in humans, we do know that in mice it involves the loss of E prostanoid receptors for prostaglandin 2 (EP2) on fibroblasts (Moore et al., 2005). The current understanding is that excessive connective tissue results from bodily tissue repair mechanisms associated with a variety of types of injury to the lungs. With injury, the inflammatory response and coagulation cascade are activated; this results in an increase in fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, inflammatory cells, and collagen deposits in the lungs, which twist the lung alveoli and capillaries out of shape. The air sacs (alveoli) fill with fluid (alveolitis), the lung capillaries become inflamed (vasculitis), and ultimately, scarring of the lung tissue (fibrosis) occurs. The end result is restrictive lung disease with loss of lung elasticity, sometimes called stiff lungs. Increased tissue resistance reduces the internal diameter of the pulmonary vascular bed, which increases the work of respiration. The lack of lung recoil and elasticity makes deflation of the lungs difficult, and compensation, through an increase in the work of breathing, must occur to achieve oxygenation. The overall results of diminished recoil include increased work of breathing, destruction of alveoli and pulmonary vessels, hypoxemia, pulmonary hypertension, and finally, cor pulmonale and heart failure. Pulmonary fibrosis can have a devastating effect on quality of life and can be fatal. The nurse’s main role includes early detection of fibrosis to minimize its severity, efficient treatment to increase or maintain the patient’s quality of life, and/or effective end of life care. Current research is focusing on finding treatments to eliminate or diminish the fibrosis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY

The incidence of pulmonary fibrosis is about 5% to 15% in the general population (Chisam & Douglas, 2002). It increases with increased doses of radiation therapy to the lung fields, increases in the volume of lung irradiated, and use of concomitant chemotherapy. Moderate or severe radiation pneumonitis occurs in 2% to 9% of patients treated with radiation and chemotherapy. Pulmonary fibrosis can take months or years to develop. Diffuse pulmonary fibrosis has several causes (Table 39-2), unlike idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), the cause of which is unknown.

| Category | Specific Causes |

|---|---|

| Occupational dust inhalation | Asbestos, beryllium, coal, cotton, detergent, gold, grain, iron, lead, malt, maple bark, moldy hay, mushrooms, paprika, plutonium (Newman et al., 2005), silica from and/or rock, sugar cane, talc (Honda et al., 2002), zinc |

| Noxious gas inhalation | Chlorine, metals, nitrogen oxide, sulfur |

| Drug sensitivities | Amiodarone (Cordarone), busulfan (Myleran), interferon alpha or gamma 1b, nitrofurantoin (Furadantin, Macrobid, Macrodantin), phenytoin (Dilantin) |

| Radiation therapy to lung fields | Radiation for treatment of cancers (breast, head and neck, lung, Hodgkin’s lymphoma) |

| Pneumonia or infection | Bird breeder’s lung, chronic bacterial pneumonia, hepatitis C infection (Aisa et al., 2001), viral pneumonia |

| Diseases | AIDS, amyloidosis, ARDS, arthritis, bagassosis, diabetes mellitus (Zisman et al., 2005), diffuse alveolar hemorrhage syndrome, eosinophilic granuloma, familial pulmonary fibrosis (FPF), GERD (Zisman et al., 2005), Hermansky Pudlak syndrome, polymyositis (Aisa et al., 2001), sarcoidosis, scleroderma, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis (Leandro & Isenberg, 2001), tuberculosis |

| Smoking, heavy | Cigarettes (Zisman et al., 2005), marijuana |

| Poisoning | Herbicide (paraquat) (Hong et al., 2005), orthophenylphenol (OPP) used in fungicides and antibacterial agents (Cheng et al., 2005) |

RISK PROFILE

• Radiation therapy to the lung fields within the past 2 years, usually for treatment of lung cancer, breast cancer, lymphoma, cancer of the larynx, and thymoma.

• Chemotherapy, single or combination (Table 39-3).

| Generic Name | Trade Name |

|---|---|

| Bleomycin | Blenoxane |

| Busulfan | Myleran |

| Carmustine | BCNU |

| Cetuximab | Erbitux |

| Cyclophosphamide | Cytoxan |

| Dactinomycin | Actinomycin D, Cosmegen |

| Docetaxel | Taxotere |

| Doxorubicin | Adriamycin |

| Gefitinib | Iressa |

| Gemcitabine | Gemzar |

| Irinotecan | Camptosar |

| Lomustine | CCNU |

| Methotrexate | Folex |

| Mitomycin | Mutamycin |

| Oxaliplatin | Eloxatin |

| Paclitaxel | Taxol |

| Vincristine | Oncovin |

• Chronic allograft rejection (Dosanjh, 2007)

• Biologic response modifiers: Interferon alpha or interferon gamma1b (Antoniou et al., 2003).

• High-dose chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, especially in patients who have undergone bone marrow transplantation (BMT).

• Lifestyle: Smoking (Grubstein et al, 2005; Zisman et al., 2005), marijuana (Phan et al, 2005), inhalation of dusts or gases, drug sensitivities, poisoning, and diseases or conditions that cause fibrosis (see Table 39-1).

• Females may be at higher risk as a result of female sex hormones, as shown by laboratory research on mice (Gharaee-Kermani et al., 2005).

• Genetic factors: Individuals with the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene (+2018) allele 2 and tumor necrosis factor–alpha gene (–308) allele 2 (Satoh et al., 2002), transfection of the Sflt-1 gene attenuated PF (Hamada et al., 2005), and telomerase RNA component (TERC) gene mutation have an increased risk of developing PF (Marrone et al., 2007). Expression of the H2-EA gene protects against bleomycin-induced PF in mice (Du et al., 2004).

• Other risk factors include increased serum levels of sialyl Lewis X-i antigen (greater than 50 units/mL) (Satoh et al., 2002); YKL-40 growth factor (Nordenbaek et al., 2005); pulmonary and activation–regulated chemokine (PARC) (Kodera et al., 2005); and CYFRA-21 (Suzuki et al., 1996). An increased serum level of CA 19-9 reflects progression of PF (Totani et al., 2005).

PROGNOSIS

The 5-year survival rate is 90% if the patient is young and has minimal fibrosis; it is 25% if the patient is older and has severe fibrosis. The mortality rate is estimated to be 1% to 2%.

PROFESSIONAL ASSESSMENT CRITERIA (PAC)

1. Classic symptoms: Dyspnea on exertion (DOE) and/or nonproductive cough (Chernecky & Sarna, 2000). Typical symptoms of drug-induced fibrosis: Dyspnea, nonproductive cough, and tachycardia.

2. History of chemotherapy (see Table 39-3), interferon alpha or interferon gamma1b, radiation therapy to the lungs, and/or BMT.

3. History of comorbidities: Smoking, inhalation of dusts or gases, drug sensitivities, poisoning, pneumonia, collagen disease.

4. Finger clubbing

5. Decreased breath sounds or crackles during auscultation of the lungs.

6. Decreased chest expansion during expiration on excursion assessment.

7. Hypoxemia (PaO2 less than 92%).

8. Hypotension

9. Tachypnea

10. Chest x-ray film (CXR): Diffuse infiltrates (Fig. 39.1), haziness around the hilar region, honeycomb or mottled lung appearance, elevation of hemidiaphragm, or pneumothorax. With pulmonary hypertension: Enlarged pulmonary artery and right atrium and ventricle.

|

| Fig. 39.1Chest x-ray film of a patient with diffuse pulmonary fibrosis. Note the shadows at the lung base and the diffuse ground-glass appearance. |

11. Pulmonary function tests: Decreased total lung capacity (TLC), diffusion capacity (DLCO), forced vital capacity (FVC) and residual volume (RV).

12. Tachycardia and prominent S2.

13. Anxiety, restlessness.

14. Labs: Total WBC count may be elevated; pH indicates acidosis (Chernecky & Berger, 2004).

15. Electrocardiogram (ECG): May show PVC, V-tach, or V-flutter.

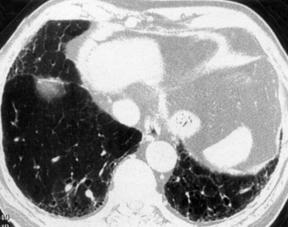

17. MRI: Low signal intensity and low contrast enhancement compared to alveolitis. CT scan of the chest (Fig. 39.2): Ground-glass opacity, decreased lung volume, pleural thickening, honeycomb or mottled lung fields, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum.

|

|

| Fig. 39.2CT scans of the chest in a patient with pulmonary fibrosis. Note the honeycomb appearance. |

18. Lung biopsy: Fibrosis, positive stain for TGF-1 or TGF-B1 or increased osteonectin expression (Siddiq et al., 2004); broncholavage shows increased hyaluronan.

19. Lung perfusion scan, FDG-PET scan or 3-D SPECT scan: Underperfusion and/or poor alveolar subunit function.

20. Cardiac catheterization: High pulmonary vascular resistance.

21. Cor pulmonale and heart failure: ECG (Chernecky et al., 2006) and CVP changes, cough, peripheral edema, jugular vein distension (JVD), nausea, anorexia, polyuria at night, weight gain, acidosis, hepatomegaly, ascites, positive hepatojugular (HJ) reflex.

NURSING CARE AND TREATMENT

1. Hold chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and interferon alpha.

2. Elevate the head of the bed to high Fowler’s position.

3. Vital signs: Assess for hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, chest pain, or fever (for pulmonary infection).

4. Obtain O2 saturation reading (signs of hypoxia include restlessness, dyspnea, anxiety, and cyanosis), PFTs (decreased DLCO), ABGs (acidosis, hypercapnia, hypoxia).

5. Administer oxygen to treat hypoxia and high-dose corticosteroids (over 100 mg/day or 1 mg/kg) for inflammation.

6. Maintain venous access with an 18 or 20-gauge peripheral IV (in adults) or a venous access device (VAD).

8. Assess for nonproductive cough.

9. Auscultate the lung fields for crackles and adventitious breath sounds; also assess for decreased chest expansion.

10. Obtain and assess laboratory test and biopsy results: WBC total, electrolytes, lung biopsy.

11. Obtain and assess chest x-ray film, CT/MRI of the chest for infiltrates, pleural thickening, pneumothorax, mottled or honey comb appearance.

12. Assess for right-side heart failure/cor pulmonale: Dependent peripheral edema, fatigue, nausea, anorexia, weight gain, hepatomegaly, JVD, systolic or diastolic murmur, prominent S2, polyuria at night, ascites.

13. Intake and output (I&O) q2-8hr.

14. Weigh patient daily and compare result to previous days; retention of 450 mL of fluid equals 1 pound of weight gain.

15. Hemodynamic monitoring (Hodges et al., 2005): Note that pulmonary hypertension can predispose a person to PA rupture when a PA catheter is placed for hemodynamic monitoring. Pulmonary hypertension causes increased PA pressures with variable PAOP, or PAWP/PAOP may be normal but PAD is increased.

16. Administer calcium channel blockers (e.g., verapamil HCl [Calan] or diltiazem [Dilacor XR]), and a vasodilator (e.g., isosorbide dinitrate [Isordil]) to treat pulmonary hypertension.

17. Administer ACE inhibitors of Ngiotensin II receptor blockers to protect the lungs form radiationinduced fibrosis (Molteni et al., 2007).

18. Anticipate administration of digitalis for cardiac dysfunction; furosemide or hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) for diuresis; and antibiotics (e.g., azithromycin [Zithromax] or levofloxacin [Levaquin]) for infection.

19. Administer by inhalation: Nitric oxide 10-20 ppm plus oral sildenafil (Viagra) 50 mg daily (which enhances the effect of nitric oxide) to reduce pulmonary vascular resistance (Ghofrani et al., 2002).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access