Care of Women with Reproductive Disorders

Objectives

1. Identify the female reproductive organs and their role in the overall health of the individual.

2. Describe normal physiology and age-related changes in the female reproductive system.

3. Discuss common menstrual disorders and their nursing interventions.

4. Explore methods of contraception.

5. Review causes and treatment of infertility.

7. Explain the screening procedures recommended for maintaining reproductive health.

8. Compare and contrast benign and malignant disorders of the female reproductive system.

9. Understand the role of robotic gynecologic surgery as an alternative to open surgery.

1. Teach techniques of breast self-examination and vulvar self-examination to a patient.

2. Plan the nursing care of a woman with a reproductive disorder.

3. Describe the causes of and interventions for common disorders of the female reproductive tract.

Key Terms

amenorrhea (ă-mĕn-ŏ-RĒ-ă, p. 904)

anovulation (ăn-ŎV-ū-LĀ-shŭn, p. 905)

climacteric (klī-MĂK-tĕr-ĭk, p. 882)

cystocele (SĬS-tō-sēl, p. 903)

dowager’s hump (p. 891)

dysmenorrhea (dĭs-mĕn-ō-RĒ-ă, p. 902)

dyspareunia (dĭs-pă-RŪ-nē-ă, p. 890)

effleurage (ĕf-lū-RĂZH, p. 902)

endometriosis (ĕn-dō-mē-trē-Ō-sĭs, p. 906)

enterocele (ĕn-TĔR-ō-sēl, p. 903)

fibroids (FĪ-broydz, p. 905)

hirsutism (HĔR-sūt-ĭszm, p. 904)

hysterectomy (hĭs-tĕr-ĔK-tō-mē, p. 903)

lymphedema (lĭm-fĕ-DĒ-mă, p. 913)

menarche (mĕ-NĂR-kē, p. 882)

menopause (MĔN-ō-păwz, p. 882)

menorrhagia (mĕn-ō-RĀ-jă, p. 904)

menses (mĕn-sēz, p. 882)

menstruation (mĕn-strū-Ā-shŭn, p. 882)

metrorrhagia (mĕ-trō-RĀ-jă, p. 904)

mittelschmerz (MĬT-ĕl-shmārts, p. 883)

myomectomy (mī-ō-MĔK-tŏ-mē, p. 905)

oligomenorrhea (ŏl-ĭ-gō-mĕn-ŏ-RĒ-ă, p. 904)

polycystic ovarian syndrome (pŏ-lē-SĬS-tĭk, p. 904)

prolapse (PRŌ-lăps, p. 882)

pruritus (prū-RĪ-tŭs, p. 890)

rectocele (RĔK-tō-sēl, p. 903)

sentinel node biopsy (SĔN-tĭ-nĕl nōd BĪ-ŏp-sē, p. 911)

stress incontinence (STRĔS ĭn-KŎN-tĭ-nĕns, p. 903)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Overview of Anatomy and Physiology of the Female Reproductive System

What are the primary external structures of the female reproductive system?

The vulva, or pudendum, is the name given to the external female genitalia. It is made up of the following structures:

What are the primary internal structures of the female reproductive system?

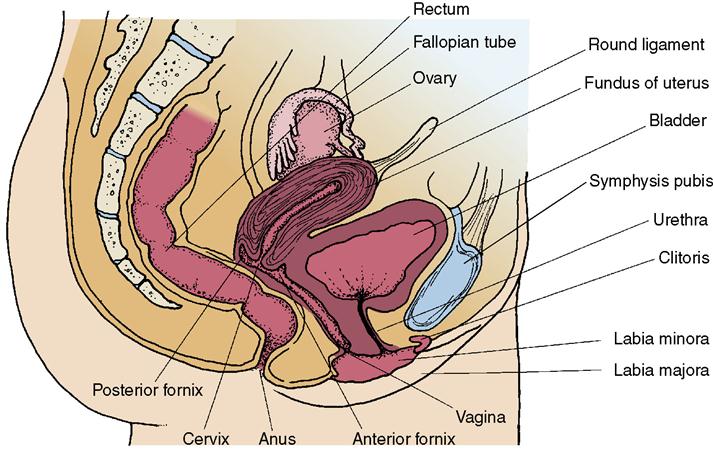

• The vagina is a muscular tube lined with membranous tissue with transverse ridges called rugae. It connects the external and internal female sexual organs (Figure 39-1).

What are the accessory organs of the female reproductive system?

The breasts, or mammary glands, located on the upper chest, are the accessory organs. They are composed of fibrous, adipose, and glandular tissue, and are responsible for lactation (milk production), which provides nourishment for the infant.

What are the phases of the female reproductive cycle during the childbearing years?

The ovarian cycle has two phases:

The menstrual cycle has four phases that are described in Box 39-1.

When does sexual development occur in the fetus?

During the first weeks of pregnancy, the male and female sexual organs are undifferentiated. After the 7th week, rapid changes occur. By the 12th week the external genitalia are formed and fully differentiated as male or female, as dictated by the union on the XX or XY chromosomes at conception. The internal structures also are forming during this period.

What changes take place as girls mature into women and become capable of reproduction?

The period of sexual maturation is called puberty. It usually occurs between ages 9 and 17 years for girls, with the average onset being 12 years of age. It involves a period of accelerated growth, then the hips begin to widen and the breasts begin to develop. Axillary and pubic hair appears. Puberty is completed by the onset of the menstrual cycle, or menses. The beginning of menstruation is called menarche. Menstruation (shedding of the uterine lining) will continue at intervals of approximately 4 weeks throughout the childbearing years except when pregnancy occurs.

What changes take place as a woman enters menopause?

Toward the end of the childbearing years, women enter the phase known as the climacteric. The menses become irregular in both pattern and flow and eventually cease altogether. Menopause has occurred when the menses have completely ceased for at least 12 months.

What changes occur with aging?

After menopause, some atrophy of the female organs, loss of elasticity, dryness of the vaginal membranes, and reduction of bone mass occur because of the decrease in estrogen levels. Loss of natural tissue elasticity may allow internal organs to sag, or prolapse, into the vagina.

Reproductive health can be disrupted by a variety of disorders, such as infertility, spontaneous abortion, premature labor, infection, and the growth of abnormal tissue, including cancerous and noncancerous tumors. As the childbearing years draw to a close, hormone production slows until the reproductive cycle ceases altogether. Nursing care of patients with diseases of the female reproductive system is further complicated by the emotional effects of such disorders. The reproductive organs represent the biologic aspect of sexual identity, and women may feel their personal identity is threatened by disorders of this system.

The female reproductive system

Menstruation

During the first year following menarche, the menstrual cycle may be somewhat irregular, but by the second year a regular cycle of approximately 28 days is normally established.

Attitudes and ideas regarding menstruation are formed early. They are based on the thoughts and beliefs expressed by other women and on personal experience. Incorrect perceptions about this normal process may increase physical discomfort or cause the young woman unnecessary embarrassment or fear. It is important that the nurse understand her own attitudes about sexuality and the reproductive process, before attempting to provide information to women about these sensitive issues. The nurse should encourage a healthy view of menarche as a natural physiologic process marking reproductive maturity.

Normal Menstrual Bleeding

Menstrual blood consists of shed endometrial tissue, blood, mucus, and vaginal and cervical cells. Shedding of the uterine lining occurs during the menstrual cycle at intervals of approximately 4 weeks, and produces bleeding. Menstrual bleeding occurs about 14 days after ovulation and lasts between 2 and 8 days. The amount of actual blood loss is only 40 to 80 mL. Blood flow may be heavy at first, but gradually reduces to spotting. The color may change from bright red to brown and the blood may have a musty odor. Once a menstrual pattern is established, a change from this pattern is reason to consult a health care provider. The length of the menstrual cycle can be influenced by stress, drugs, nutrition, or illness. Women should be encouraged to keep a calendar of their individual menstrual cycle to determine regularity and to recognize deviations. Mild cramping may occur, and some mood swings may be associated with the hormonal changes. Mittelschmerz is a sharp pain in the right or left lower quadrant, sometimes felt at the midcycle around the time of ovulation; the pain may last a few hours. Some women are sensitive to this phenomenon, and others never experience it.

Normal Vaginal Discharge

The vagina is a warm, moist, dark vault in which microorganisms can flourish. Normal vaginal secretions contain cervical mucus, endometrial fluid, exudate from Bartholin’s glands and Skene’s ducts, and products of normal flora. An increase in secretions normally occurs during pregnancy and at the midpoint of the menstrual cycle when ovulation occurs, and a decrease in secretions normally occurs after menopause. The main line of defense against infection is lactic acid, which causes an acidic pH. Any change in this pH can result in infection.

Normal vaginal discharge has an off-white color and is without odor. If the vaginal discharge develops an odor, changes color or consistency, or causes irritation or burning of the vaginal mucosa, a health care provider should be consulted.

Normal Breasts

Breasts are made of adipose tissue, milk-producing glands called lobules, ducts, and fibrous tissue that rest on the chest muscle. They may not be completely symmetrical (one may be slightly larger than the other) and may feel a bit lumpy and tender, especially during the middle of the menstrual cycle. Age, pregnancy, medication, and diet can affect the way the breasts feel. As the woman ages, the denseness and adipose tissue content decreases. Birth control pills, hormone replacement therapy, and pregnancy may cause the breasts to increase in size.

Contraception and Fertility

Many women start sexual relationships and risk pregnancy before they are ready to have children. Other women give birth, and do not wish to bear more children. For these groups of women, information concerning techniques of contraception is essential to prevent unwanted, unintended pregnancies. Many sexually active women of childbearing age are concerned about regulating, planning, or preventing pregnancy. With the assistance of a health care provider, they can select the birth control method best suited to their physical health, sexual activity, desire to have children at a future date, cultural and religious beliefs about family regulation, and lifestyle.

Contraceptive Options

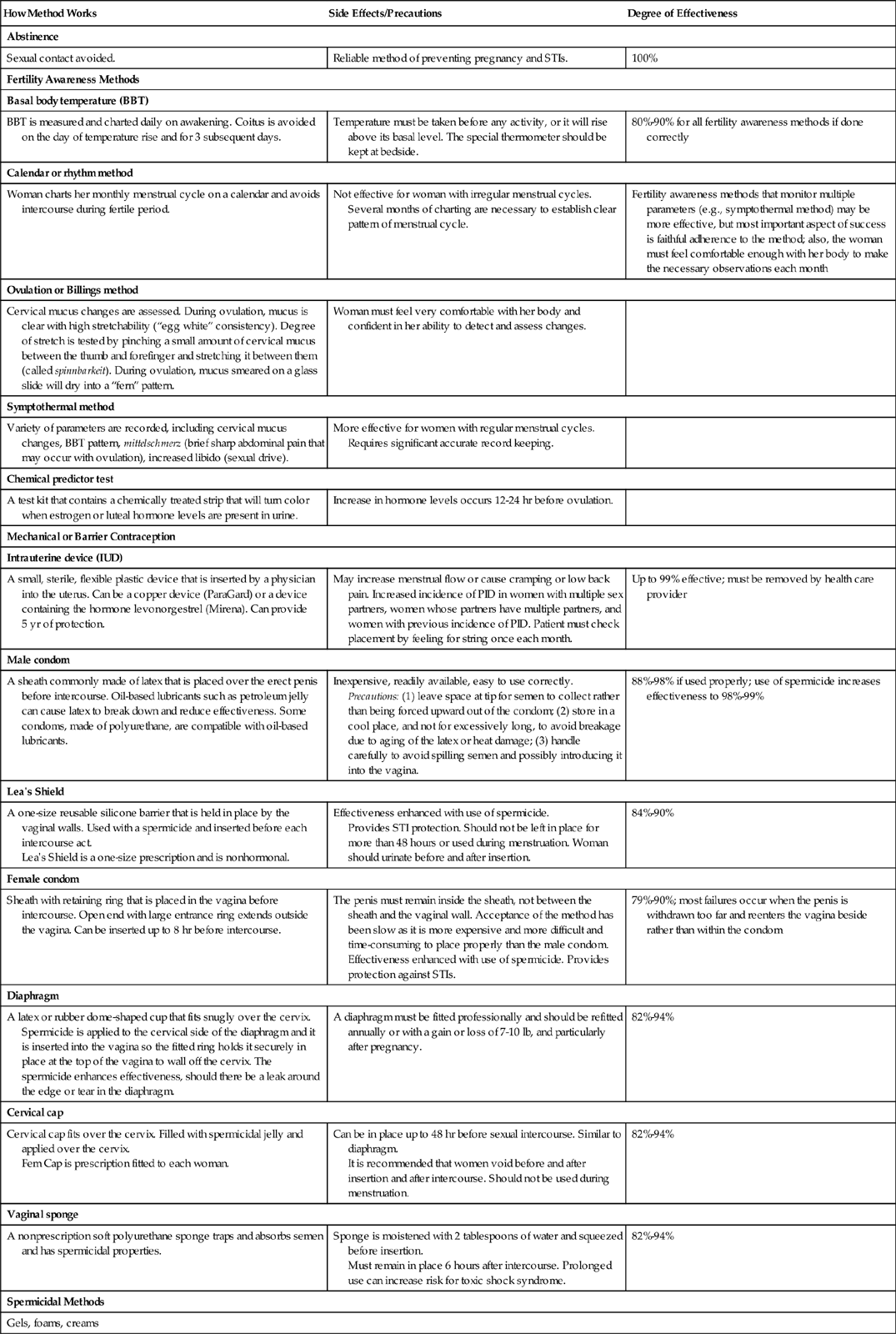

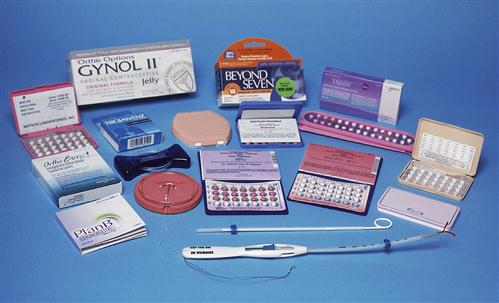

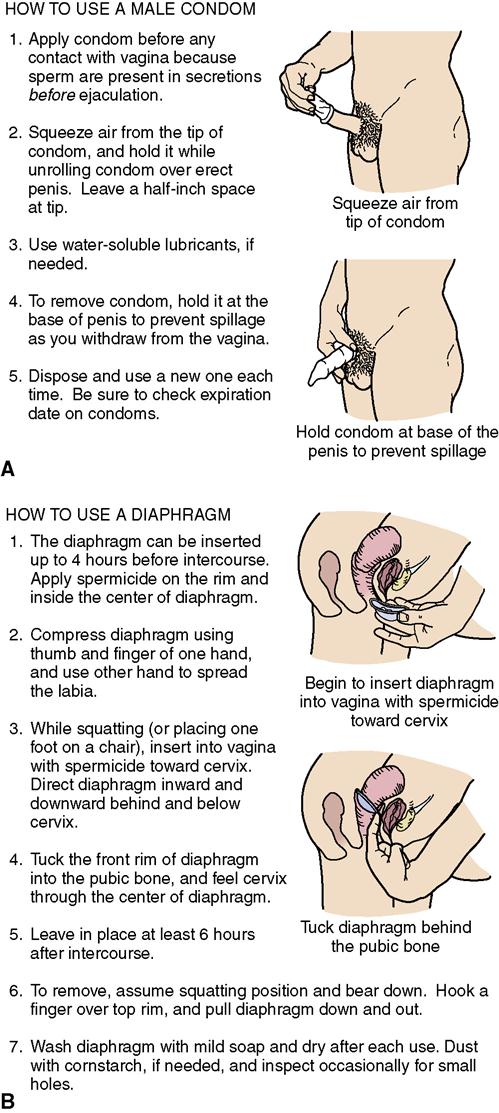

Women should make an informed decision concerning methods of reliable birth control, and nurses are responsible for providing comprehensive education concerning the advantages, limitations, and side effects of the various contraceptive drugs and devices (Table 39-1). Some methods of birth control provide protection against sexually transmitted infections (STIs), but some do not. Newer contraceptive regimens reduce the hormone-free interval, thereby decreasing the occurrence of menstrual periods. The best contraceptive methods for young adults are abstinence, the use of planned contraception, the correct use of condoms to prevent STIs (Figure 39-2), and lifestyle counseling.

Table 39-1

| How Method Works | Side Effects/Precautions | Degree of Effectiveness |

| Abstinence | ||

| Sexual contact avoided. | Reliable method of preventing pregnancy and STIs. | 100% |

| Fertility Awareness Methods | ||

| Basal body temperature (BBT) | ||

| BBT is measured and charted daily on awakening. Coitus is avoided on the day of temperature rise and for 3 subsequent days. | Temperature must be taken before any activity, or it will rise above its basal level. The special thermometer should be kept at bedside. | 80%-90% for all fertility awareness methods if done correctly |

| Calendar or rhythm method | ||

| Woman charts her monthly menstrual cycle on a calendar and avoids intercourse during fertile period. | Not effective for woman with irregular menstrual cycles. Several months of charting are necessary to establish clear pattern of menstrual cycle. | Fertility awareness methods that monitor multiple parameters (e.g., symptothermal method) may be more effective, but most important aspect of success is faithful adherence to the method; also, the woman must feel comfortable enough with her body to make the necessary observations each month |

| Ovulation or Billings method | ||

| Cervical mucus changes are assessed. During ovulation, mucus is clear with high stretchability (“egg white” consistency). Degree of stretch is tested by pinching a small amount of cervical mucus between the thumb and forefinger and stretching it between them (called spinnbarkeit). During ovulation, mucus smeared on a glass slide will dry into a “fern” pattern. | Woman must feel very comfortable with her body and confident in her ability to detect and assess changes. | |

| Symptothermal method | ||

| Variety of parameters are recorded, including cervical mucus changes, BBT pattern, mittelschmerz (brief sharp abdominal pain that may occur with ovulation), increased libido (sexual drive). | More effective for women with regular menstrual cycles. Requires significant accurate record keeping. | |

| Chemical predictor test | ||

| A test kit that contains a chemically treated strip that will turn color when estrogen or luteal hormone levels are present in urine. | Increase in hormone levels occurs 12-24 hr before ovulation. | |

| Mechanical or Barrier Contraception | ||

| Intrauterine device (IUD) | ||

| A small, sterile, flexible plastic device that is inserted by a physician into the uterus. Can be a copper device (ParaGard) or a device containing the hormone levonorgestrel (Mirena). Can provide 5 yr of protection. | May increase menstrual flow or cause cramping or low back pain. Increased incidence of PID in women with multiple sex partners, women whose partners have multiple partners, and women with previous incidence of PID. Patient must check placement by feeling for string once each month. | Up to 99% effective; must be removed by health care provider |

| Male condom | ||

| A sheath commonly made of latex that is placed over the erect penis before intercourse. Oil-based lubricants such as petroleum jelly can cause latex to break down and reduce effectiveness. Some condoms, made of polyurethane, are compatible with oil-based lubricants. | Inexpensive, readily available, easy to use correctly. Precautions: (1) leave space at tip for semen to collect rather than being forced upward out of the condom; (2) store in a cool place, and not for excessively long, to avoid breakage due to aging of the latex or heat damage; (3) handle carefully to avoid spilling semen and possibly introducing it into the vagina. | 88%-98% if used properly; use of spermicide increases effectiveness to 98%-99% |

| Lea’s Shield | ||

| A one-size reusable silicone barrier that is held in place by the vaginal walls. Used with a spermicide and inserted before each intercourse act. Lea’s Shield is a one-size prescription and is nonhormonal. | Effectiveness enhanced with use of spermicide. Provides STI protection. Should not be left in place for more than 48 hours or used during menstruation. Woman should urinate before and after insertion. | 84%-90% |

| Female condom | ||

| Sheath with retaining ring that is placed in the vagina before intercourse. Open end with large entrance ring extends outside the vagina. Can be inserted up to 8 hr before intercourse. | The penis must remain inside the sheath, not between the sheath and the vaginal wall. Acceptance of the method has been slow as it is more expensive and more difficult and time-consuming to place properly than the male condom. Effectiveness enhanced with use of spermicide. Provides protection against STIs. | 79%-90%; most failures occur when the penis is withdrawn too far and reenters the vagina beside rather than within the condom |

| Diaphragm | ||

| A latex or rubber dome-shaped cup that fits snugly over the cervix. Spermicide is applied to the cervical side of the diaphragm and it is inserted into the vagina so the fitted ring holds it securely in place at the top of the vagina to wall off the cervix. The spermicide enhances effectiveness, should there be a leak around the edge or tear in the diaphragm. | A diaphragm must be fitted professionally and should be refitted annually or with a gain or loss of 7-10 lb, and particularly after pregnancy. | 82%-94% |

| Cervical cap | ||

| Cervical cap fits over the cervix. Filled with spermicidal jelly and applied over the cervix. Fem Cap is prescription fitted to each woman. | Can be in place up to 48 hr before sexual intercourse. Similar to diaphragm. It is recommended that women void before and after insertion and after intercourse. Should not be used during menstruation. | 82%-94% |

| Vaginal sponge | ||

| A nonprescription soft polyurethane sponge traps and absorbs semen and has spermicidal properties. | Sponge is moistened with 2 tablespoons of water and squeezed before insertion. Must remain in place 6 hours after intercourse. Prolonged use can increase risk for toxic shock syndrome. | 82%-94% |

| Spermicidal Methods | ||

| Gels, foams, creams | ||

| Work by killing sperm within the vagina. Must be applied before intercourse. | Available without prescription. More effective when used as an adjunct to condoms, diaphragms, and caps. | Foam alone, 79%-90%; creams and gels alone, 79% |

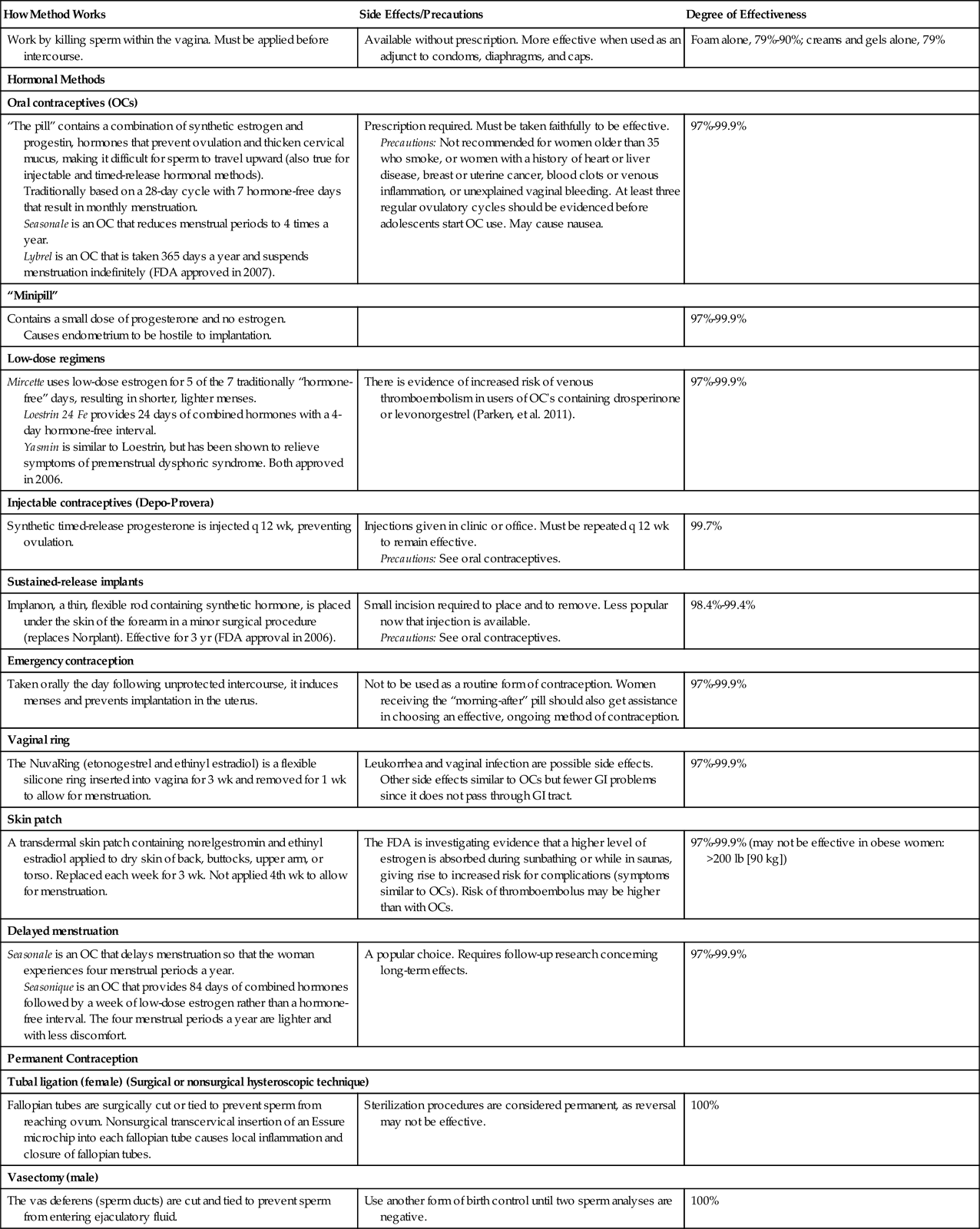

| Hormonal Methods | ||

| Oral contraceptives (OCs) | ||

| “The pill” contains a combination of synthetic estrogen and progestin, hormones that prevent ovulation and thicken cervical mucus, making it difficult for sperm to travel upward (also true for injectable and timed-release hormonal methods). Traditionally based on a 28-day cycle with 7 hormone-free days that result in monthly menstruation. Seasonale is an OC that reduces menstrual periods to 4 times a year. Lybrel is an OC that is taken 365 days a year and suspends menstruation indefinitely (FDA approved in 2007). | Prescription required. Must be taken faithfully to be effective. Precautions: Not recommended for women older than 35 who smoke, or women with a history of heart or liver disease, breast or uterine cancer, blood clots or venous inflammation, or unexplained vaginal bleeding. At least three regular ovulatory cycles should be evidenced before adolescents start OC use. May cause nausea. | 97%-99.9% |

| “Minipill” | ||

| Contains a small dose of progesterone and no estrogen. Causes endometrium to be hostile to implantation. | 97%-99.9% | |

| Low-dose regimens | ||

| Mircette uses low-dose estrogen for 5 of the 7 traditionally “hormone-free” days, resulting in shorter, lighter menses. Loestrin 24 Fe provides 24 days of combined hormones with a 4-day hormone-free interval. Yasmin is similar to Loestrin, but has been shown to relieve symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric syndrome. Both approved in 2006. | There is evidence of increased risk of venous thromboembolism in users of OC’s containing drosperinone or levonorgestrel (Parken, et al. 2011). | 97%-99.9% |

| Injectable contraceptives (Depo-Provera) | ||

| Synthetic timed-release progesterone is injected q 12 wk, preventing ovulation. | Injections given in clinic or office. Must be repeated q 12 wk to remain effective. Precautions: See oral contraceptives. | 99.7% |

| Sustained-release implants | ||

| Implanon, a thin, flexible rod containing synthetic hormone, is placed under the skin of the forearm in a minor surgical procedure (replaces Norplant). Effective for 3 yr (FDA approval in 2006). | Small incision required to place and to remove. Less popular now that injection is available. Precautions: See oral contraceptives. | 98.4%-99.4% |

| Emergency contraception | ||

| Taken orally the day following unprotected intercourse, it induces menses and prevents implantation in the uterus. | Not to be used as a routine form of contraception. Women receiving the “morning-after” pill should also get assistance in choosing an effective, ongoing method of contraception. | 97%-99.9% |

| Vaginal ring | ||

| The NuvaRing (etonogestrel and ethinyl estradiol) is a flexible silicone ring inserted into vagina for 3 wk and removed for 1 wk to allow for menstruation. | Leukorrhea and vaginal infection are possible side effects. Other side effects similar to OCs but fewer GI problems since it does not pass through GI tract. | 97%-99.9% |

| Skin patch | ||

| A transdermal skin patch containing norelgestromin and ethinyl estradiol applied to dry skin of back, buttocks, upper arm, or torso. Replaced each week for 3 wk. Not applied 4th wk to allow for menstruation. | The FDA is investigating evidence that a higher level of estrogen is absorbed during sunbathing or while in saunas, giving rise to increased risk for complications (symptoms similar to OCs). Risk of thromboembolus may be higher than with OCs. | 97%-99.9% (may not be effective in obese women: >200 lb [90 kg]) |

| Delayed menstruation | ||

| Seasonale is an OC that delays menstruation so that the woman experiences four menstrual periods a year. Seasonique is an OC that provides 84 days of combined hormones followed by a week of low-dose estrogen rather than a hormone-free interval. The four menstrual periods a year are lighter and with less discomfort. | A popular choice. Requires follow-up research concerning long-term effects. | 97%-99.9% |

| Permanent Contraception | ||

| Tubal ligation (female) (Surgical or nonsurgical hysteroscopic technique) | ||

| Fallopian tubes are surgically cut or tied to prevent sperm from reaching ovum. Nonsurgical transcervical insertion of an Essure microchip into each fallopian tube causes local inflammation and closure of fallopian tubes. | Sterilization procedures are considered permanent, as reversal may not be effective. | 100% |

| Vasectomy (male) | ||

| The vas deferens (sperm ducts) are cut and tied to prevent sperm from entering ejaculatory fluid. | Use another form of birth control until two sperm analyses are negative. | 100% |

Data from Hacker, N., Gambone, J., & Habel, C./ (2010). Essentials of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 5th Ed., Philadelphia: Saunders., Hatcher, R., Trussell, A., Nelson, W., et al. (2007). Contraceptive Technology (19th ed.). New York: Ardent Media; Yranski, P., & Gamache, M. (2009). New options for barrier contraceptives, JOGNN 37(3):384-389; Fischer, M. (2009). Implanon: a new contraceptive implant, JOGNN 34(3):361-368; Fontenot, H., & Harris, A. (2009). Latest advances in hormonal contraception, JOGNN 34(3):369-371; Fantasia, H. (2009). Options for intrauterine contraception, JOGNN 34(3):375-379; and Theroux, R. (2009). Hysteroscopic approach to sterilization, JOGNN 34(3):356-360.

Oral Contraceptives

Oral contraceptives (OCs) are the most popular method of reversible hormonal contraception. OCs are effective if used properly, and offer noncontraceptive benefits—relief from breast tenderness, bloating, and premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms—but OCs have contraindications and cautions for use (Samra-Latif, 2011) (Figure 39-3).  The nurse should counsel the woman concerning options, and collect data that can determine which contraceptive choice is best for her. The health care provider assists the woman in making the final choice. Traditional OC regimens are based on a 28-day cycle with a 7-day hormone-free interval that allows for menstruation and gonadotropin levels to rise and for ovarian follicular growth to occur. When the OC cycle is not resumed on schedule, the risk of unplanned pregnancy occurs. Newer OCs reduce the hormone-free interval, thereby reducing menstrual discomforts and decreasing risk of contraceptive failure (Borgelt-Hansen, 2011). Seasonale is a popular oral contraceptive that provides delayed menstruation, so that a woman has only four menstrual periods a year (Drug.com, 2011). Another regimen (Lybrel) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2007; the regimen involves low-dose combined hormones for 365 days per year without a hormone-free interval, allowing a woman to postpone menstruation indefinitely. The first “four-phasic” OC, estradiol valerate and dienogest (Natazia), was approved in 2010. Natazia provides four dosage combinations of progestin and estrogen hormones during each 28-day cycle.

The nurse should counsel the woman concerning options, and collect data that can determine which contraceptive choice is best for her. The health care provider assists the woman in making the final choice. Traditional OC regimens are based on a 28-day cycle with a 7-day hormone-free interval that allows for menstruation and gonadotropin levels to rise and for ovarian follicular growth to occur. When the OC cycle is not resumed on schedule, the risk of unplanned pregnancy occurs. Newer OCs reduce the hormone-free interval, thereby reducing menstrual discomforts and decreasing risk of contraceptive failure (Borgelt-Hansen, 2011). Seasonale is a popular oral contraceptive that provides delayed menstruation, so that a woman has only four menstrual periods a year (Drug.com, 2011). Another regimen (Lybrel) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2007; the regimen involves low-dose combined hormones for 365 days per year without a hormone-free interval, allowing a woman to postpone menstruation indefinitely. The first “four-phasic” OC, estradiol valerate and dienogest (Natazia), was approved in 2010. Natazia provides four dosage combinations of progestin and estrogen hormones during each 28-day cycle.

Emergency Contraception

Known as the “morning-after” pill, emergency contraception is indicated after unprotected intercourse. It is not meant to be used on a regular basis, but was developed to decrease the number of unwanted pregnancies and elective abortions. Emergency contraception prevents pregnancy in one of three ways: by preventing ovulation or fertilization, slowing transport of the sperm and egg, or altering the uterine lining to prevent implantation. “Plan B one-step” is one tablet of levonorgestrel only, taken within 72 hours of unprotected sex; the tablet was approved in July 2009 and is available without prescription to women over 17 years of age. Next Choice, a generic version of the original two-pill plan B contraception, is available by prescription to those age 17 or younger. Ulipristol acetate (Ella) is a one-pill emergency contraceptive that is approved for use for up to 5 days after unprotected sex (Fine, 2010). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated in July 2009 that emergency contraception is safe for women of all ages (ACOG, 2009a).

The woman is advised to take an antiemetic before each dose of emergency contraception to minimize nausea and vomiting. Since emergency contraception is not effective if the woman is already pregnant, failure to menstruate by 21 days after initiation of emergency contraception requires evaluation for pregnancy. There is no evidence that emergency contraception causes abortion, ectopic pregnancy, or fetal anomalies if taken when the woman is already pregnant (Fontenot & Harris, 2008).

A copper intrauterine device (IUD) can be inserted up to 7 days after unprotected sexual intercourse to prevent implantation of the zygote in women who prefer long-term contraception. A woman who seeks emergency contraception should be educated concerning methods of birth control and prevention of STIs.

Infertility

Many women dream of having children but find difficulty in conceiving. For these women, preconception guidance and infertility treatments may be helpful. Preconception guidance involves gathering data concerning the woman and her partner in order to provide information necessary to make an informed, individualized decision concerning conception or fertility assistance. Screening for genetic disorders may be required.

Primary infertility is the inability of the couple to conceive a child after at least 1 year of active, unprotected sexual relations without using contraceptives. Secondary infertility is the inability to conceive after having once conceived, or the inability to maintain a pregnancy long enough to deliver a viable infant. Approximately 10% to 20% of American couples have infertility, and today more couples are seeking medical intervention. Infertility services also assist women who wish to have a child without a male partner.

The ability to conceive depends primarily on both partners having normal reproductive physiology, physiologically and psychologically sensitive interaction, and proper timing of intercourse. Factors in the male that contribute to infertility include problems with the sperm, abnormal ejaculation, abnormal erections, and abnormal seminal fluid. Chapter 40 presents a discussion of problems in the male reproductive system. Factors contributing to infertility in a woman include:

• An abnormality in the pathway between the cervix and fallopian tube

• An abnormality in the endometrium of the uterus, or malformation of the uterus

• Tumors in the reproductive tract

• Vaginal or cervical environment that is inhospitable to sperm motility or viability.

Repeated pregnancy loss can be caused by:

• An abnormality in fetal chromosomes that result in spontaneous abortion

• Abnormalities of the cervix or uterus

• Disorders of the endocrine or immune system

Preconception counseling helps the couple evaluate problems or risks related to conception.

There are many causes of infertility; some involve a problem in the woman, and some in the man. Diagnosis includes a detailed health history and laboratory tests such as serum prolactin levels and other endocrine evaluations, semen analysis, sperm antibody agglutination studies, and chromosome studies. Tests for tubal patency and other possible abnormalities in both the male and female reproductive tract may also be needed.

Nursing Management

Interventions the nurse can discuss with the patient regarding infertility may include nonmedical actions such as:

• Using water-soluble lubricants during intercourse, because these do not have spermicidal properties.

• Referring the couple for stress management, nutrition counseling, and lifestyle analysis.

Interventions for infertility can also involve medical therapy such as the use of drugs that stimulate ovulation. Drugs to treat thyroid or adrenal problems in the man may enhance spermatogenesis.

Assisted Reproduction

Assisted reproductive therapies (ARTs) (Box 39-2) are available, but are associated with many ethical and legal issues such as the risk for having a multifetal pregnancy, freezing embryos for later use, and the use of a surrogate mother. Micromanipulation allows the removal of a single cell from an embryo for genetic analysis. Defective genes can be replaced. Success rates of ARTs vary, and the procedure is usually expensive and rarely is covered by health insurance. Donor eggs or donor sperm can be used, making future legal challenges for custody a possibility.

Menopause

Menopause is defined by the World Health Organization as the cessation of menses for 12 consecutive months due to a decrease in estrogen production. The perimenopausal period or climacteric is the time around the actual cessation of the menstrual cycle. Signs and symptoms of the climacteric and menopause include hot flashes (a sensation of warmth), hot flushes (a visible redness and moistness of the skin), and night sweats due to vasomotor instability resulting from low estrogen levels. These symptoms usually decrease as the woman’s body adjusts to the lower level of estrogen. Changes in the menstrual flow and menstrual irregularity require the woman to “be prepared” for an unexpected menstrual period. The aging process—as well as the decrease in estrogen levels—can cause thinning of the vaginal walls (atrophy), dryness, and itching of the vagina (pruritus). These changes may result in painful sexual relations (dyspareunia) and can also lead to increased susceptibility to infections because the vaginal pH increases.

The psychological response to menopause represents a change that can challenge a woman’s coping skills and may require family support to help the woman maintain a sense of purpose in life. Other women feel a sense of freedom from the need for contraception or medication for cramping.

Western culture values youth and beauty; therefore some women may see the onset of menopause as a loss of attractiveness, and the first step toward old age. Other cultural groups value the wisdom gained from life’s experiences, and for women in these cultures the onset of menopause may carry less negative psychological impact. Nurses must understand the perceptions of the woman and the family before designing and implementing a teaching plan to address this “change in life.”

Health Risks of Menopause

The major health problems that occur at or after menopause include the development of osteoporosis and coronary heart disease.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a decrease in bone mass that raises the risk for bone fractures. The decrease in estrogen during menopause slows bone growth; therefore bone deteriorates and thins before new bone growth occurs. Estrogen also enables vitamin D to assist in calcium absorption in the intestine, and a decrease in estrogen is associated with a decrease in calcium, which is essential to healthy bone tissue. Box 39-3 provides a list of some lifestyle activities that may increase the risk of developing osteoporosis. A new drug, denosumab (Xgeva, Prolia), developed for women who have osteoporosis and are at risk for facture was approved by the FDA in 2010 and is often prescribed with vitamin D and calcium supplements. Women are then monitored for low calcium levels and jaw osteonecrosis. The use of nitroglycerin ointment to increase bone density is currently under study (Khosla, 2011).

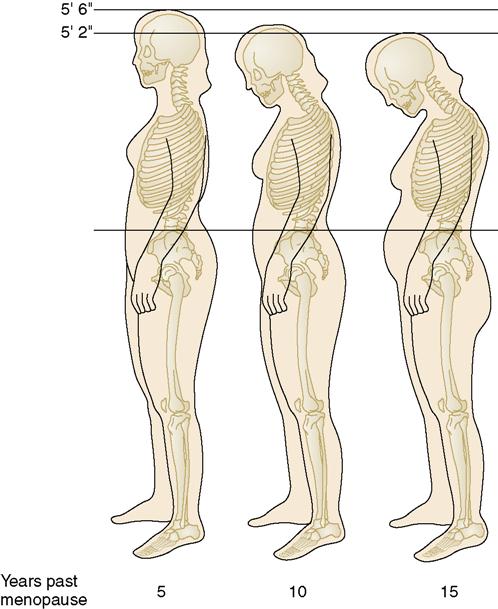

The first signs of osteoporosis are loss of height, back pain, and the development of a so-called dowager’s hump in which vertebrae fail to support the upper body in an upright position (Figure 39-4). The ACOG Women’s Health Care Physicians recommend bone density screening for menopausal women.

Coronary Heart Disease

The decrease in hormones in postmenopausal women causes an increased risk for coronary heart disease due to changes in lipid metabolism and a rise in total cholesterol. Diet and exercise can have a positive effect in minimizing the effects of these risks. See Chapters 20 and 21 for details concerning cardiovascular diseases.

Treatment Options During Menopause

Hormone Therapy

In the past, hormone (estrogen) replacement therapy (HRT) was the cornerstone of interventions to reduce the discomforts of menopause (hot flashes and vaginal atrophy) and protect women from developing coronary heart disease and osteoporosis. Research offers evidence that HRT can increase the risk of blood clots, stroke, heart attack, and breast cancer. The ACOG recommends careful selection of patients for HRT, and detailed education concerning risks of therapy. Current guidelines state that hormone therapy should be used by well-informed and well-monitored patients and for menopausal symptoms only, at the lowest effective dose (Prentice, 2009).

Bioidentical hormones

Bioidentical hormones such as oral estradiol, estradiol transdermal patches, or oral micronized progesterone (Prometrium) are clinically synthesized from steroidal molecules taken from wild yam or soy, but have chemical structures identical to hormones produced in the human body. They differ from “natural hormones” such as conjugated equine hormone (Premarin), which comes from the urine of pregnant mares and has a chemical structure different from the human. Progesterone is a bioidentical hormone that has a different chemical structure than progestins such as synthetically produced medroxyprogesterone (Provera). Both synthetic and bioidentical hormones interact with the same estrogen and progesterone receptors on target cells, but their physiologic side effects maybe different.

Bioidentical hormones that are made (compounded) by individual pharmacies are not FDA regulated or approved and may not be monitored for consistency and purity (Borsage & Freeman, 2009). Nurses should be alert to research findings that involve “hormone therapy” and should inquire if the hormones researched are bioidentical or synthetic (Weil, 2009).

Alternative Therapies

Some CAM therapies have been helpful in relieving specific discomforts of menopause. Homeopathy, acupuncture, and certain herbs may offer relief, but each may have contraindications as well. Herbal therapy has not been fully researched or regulated, and some side effects or interactions with food or drugs are possible. Phytoestrogens, soy products, and vitamins B, C, and E have also been helpful in relieving menopausal discomforts.

Medications such as alendronate (Fosamax) can be prescribed for women with osteoporosis, but side effects should be explained carefully. After taking Fosamax, the woman must be able to remain upright for at least 30 minutes. Diet, exercise, and support groups are very effective in helping to manage menopause. When hot flashes significantly affect a woman’s quality of life, nonhormonal medication may be recommended. Studies have shown that medications such as venlafaxine (Effexor) and clonidine (Catapres), soy isoflavones, and CAM therapies such as black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) may offer relief of hot flash symptoms (NCAM, 2011).

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Women’s health care can be defined as the promotion of the physical, psychological, and spiritual well-being of women. In the twenty-first century, women are increasingly economically independent and empowered to make health care decisions. Health care education of the adolescent includes information concerning puberty, menstruation, and sexuality. A teen needs information concerning safe sex, contraceptives, and choices concerning high-risk behaviors. Adult women require information concerning Papanicolaou (Pap) smears, breast self-examination, nutrition, exercise, and lifestyle management. Perinatal education is important. Older women require information regarding menopause, long-term illness, and disabilities that affect health care needs. Today many older women live alone with below-poverty-level income and are without caregivers or easy access to health care. The nurse must have an understanding of these needs and of the normal physiologic changes of each age group in order to devise a plan of care to maintain health or treat illness.

It is of utmost importance that women of all ages be knowledgeable about the function of their bodies, health care needs, and signs and symptoms of wellness, as well as those of illness. Young women often first enter the health care system for a Pap smear or for contraceptive advice. Support, reassurance, and understanding of cultural and personal needs are the primary responsibilities of the nurse during this first contact. A complete history, physical examination, age-appropriate screening tests with clear interpretations, referrals, and education concerning nutrition, lifestyle, and health care to meet individual needs are essential responsibilities of the nurse and the health care team.

Health Screening and Assessments

Health screening is a form of preventive care. Primary prevention is designed to decrease the probability of becoming ill (for example, by maintaining a health or nutrition history, and by providing immunizations). Secondary prevention is designed to focus on detection of specific at-risk diseases so that early treatment may be given (such as annual mammograms). Tertiary prevention minimizes the impact of an already-diagnosed condition.

All adult women may be at risk for obesity, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, osteoporosis, and dental disease. Pregnant women or women planning pregnancy may be at risk for a folic acid deficiency that could result in a neural tube defect in the developing fetus; therefore prenatal vitamins, including folic acid supplements, may be prescribed.

Health screening begins with the woman’s visit to her health care provider. It is your responsibility to introduce yourself, ask pertinent questions, and document all information gathered. The data collected identify the patient and summarize her personal health history, the community in which she lives, and her available support system. Some information concerning the woman’s culture, lifestyle, and usual coping mechanisms will enable the design of an individualized plan of care. All data collection should include information regarding use of nonprescription as well as prescription medications and CAM therapy.

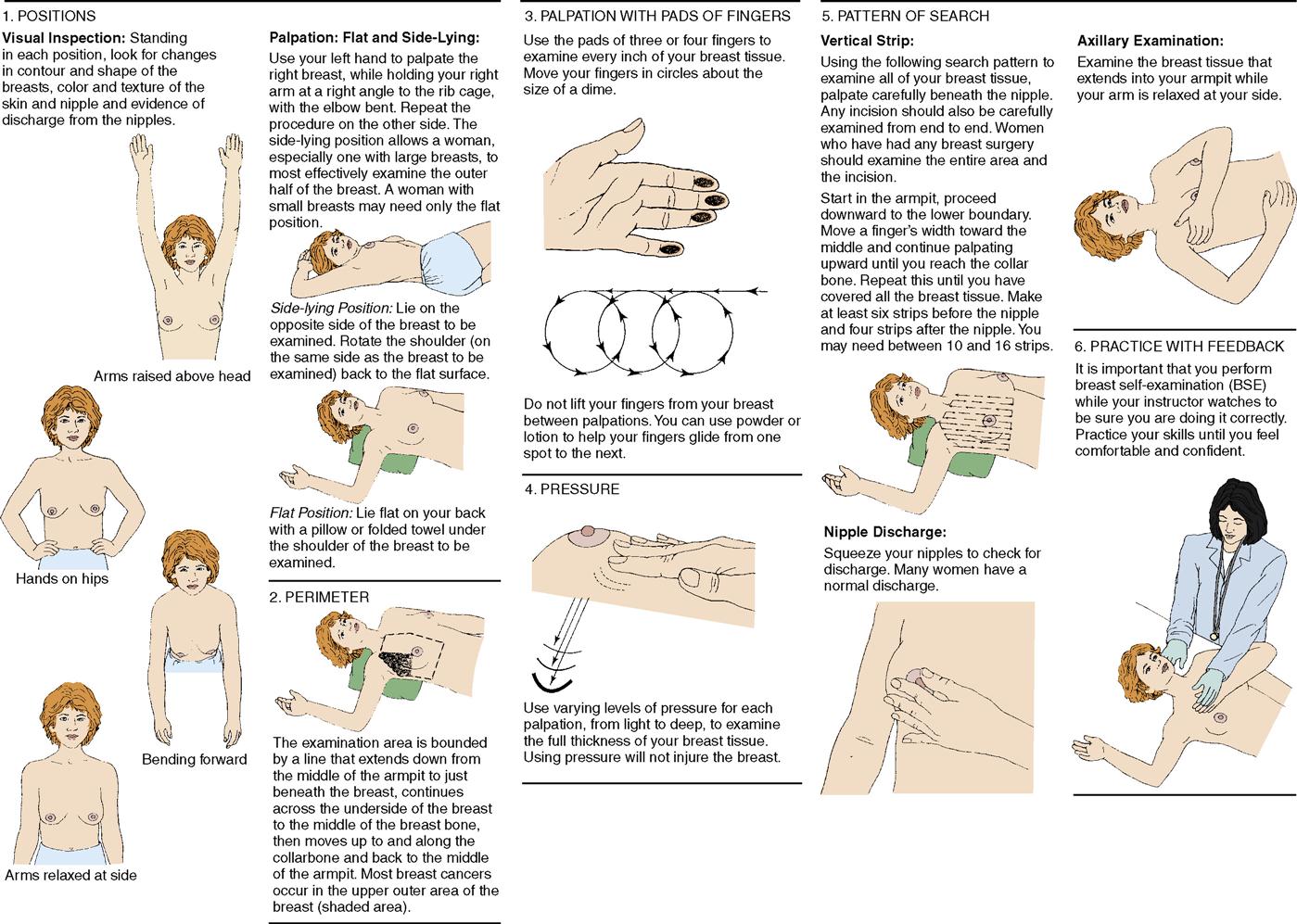

Breast Self-Examination

Breast self-examination (BSE) should be done monthly, about 1 week after menstruation begins, or on a specific date each month after menopause. The nurse plays a major role in teaching and encouraging women to perform BSE to detect breast lumps and thickened areas. Figure 39-5 illustrates the steps in the procedure. In addition, the American Cancer Society has videotapes available that demonstrate BSE.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Clinical Cues

Clinical Cues