Care of Patients with Pituitary, Thyroid, Parathyroid, and Adrenal Disorders

Objectives

2. Outline three nursing interventions appropriate for each problem of hypopituitarism.

4. Compare and contrast the symptoms of hypoparathyroidism with hyperparathyroidism.

5. Identify six signs and symptoms of adrenocortical insufficiency (Addison’s disease).

2. Select appropriate nursing interventions for a patient with adrenal insufficiency.

3. Implement patient teaching for the patient with hypothyroidism.

4. Plan postoperative assessment and nursing care for a patient who has had a hypophysectomy.

5. Evaluate the nursing care of a patient who has had a thyroidectomy.

6. Identify nursing diagnoses and appropriate interventions for a patient with diabetes insipidus.

7. Assist with development of a teaching plan for the patient taking a corticosteroid.

Key Terms

ablation therapy (ăb-LĀ-shŭn THĔR-ă-pē, p. 840)

acromegaly (ăk-rō-MĔG-ă-lē, p. 834)

addisonian crisis (p. 848)

anosmia (ăn-ŎS-mē-ă, p. 835)

apathetic thyrotoxicosis (ă-pă-THĔ-tĭk thī-rō-tŏk-sĭ-KŌ-sĭs, p. 839)

autoimmune thyroiditis (p. 845)

benign pituitary adenoma (bĕ-NĪN pĭ-TŪ-ĭ-tĕr-ē ă-dĕ-NŌ-mă, p. 834)

catecholamines (kăt-ĕ-KŌL-ă-mēnz, p. 847)

Chvostek sign (p. 845)

Cushing syndrome (p. 852)

diabetes insipidus (DI) (p. 835)

diuresis (dī-ŭr-RĒ-sĭs, p. 836)

exophthalmos (ĕk-sŏf-THĂL-mŏs, p. 839)

gigantism (jī-GĂN-tĭzm, p. 834)

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (p. 845)

hyponatremia (hī-pō-nă-TRĒ-mē-ă, p. 838)

hypothyroidism (p. 840)

lability (p. 852)

myxedema coma (p. 845)

Sheehan syndrome (SHĒ-hăn SĬN-drōm, p. 835)

syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) (p. 837)

tetany (TĔT-ă-nē, p. 841)

thyroid crisis (THĪ-royd krī-sĭs, p. 840)

thyroid storm (TS) (THĪ-royd, p. 843)

Trousseau sign (p. 845)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit

Disorders of the pituitary gland

Many syndromes can occur as a result of a pituitary disorder. Among the more common disorders of the pituitary are:

• Hypofunction of the pituitary gland

• Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion

Pituitary tumors

Tumors of the pituitary gland account for about 10% of all intracranial tumors. Local symptoms are more likely to occur when the tumor is large and creates pressure within the brain. Smaller tumors, as well as the larger ones, can cause various systemic symptoms and endocrine dysfunctions, depending on whether they stimulate or inhibit the secretion of particular hormones.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

A tumor of the pituitary is usually a benign pituitary adenoma. This tumor secretes growth hormone (GH), leading to continued growth of bones and soft tissues. There is increased pressure within the optic chiasm (the part of the brain where the optic nerve fibers cross), which, if not relieved, will destroy the optic nerve. It also antagonizes (acts against) the effect of the hormone insulin, resulting in an increase in blood glucose and glucose intolerance (see Chapter 38).

Signs and Symptoms

Local symptoms of pituitary adenoma include headache from the pressure of the tumor, and visual disturbance—with possible blindness—from pressure within the optic chiasm. Systemic symptoms may be vague, and progress very slowly. Personality changes, weakness, fatigue, and vague abdominal pain can be present for years before the condition is diagnosed correctly.

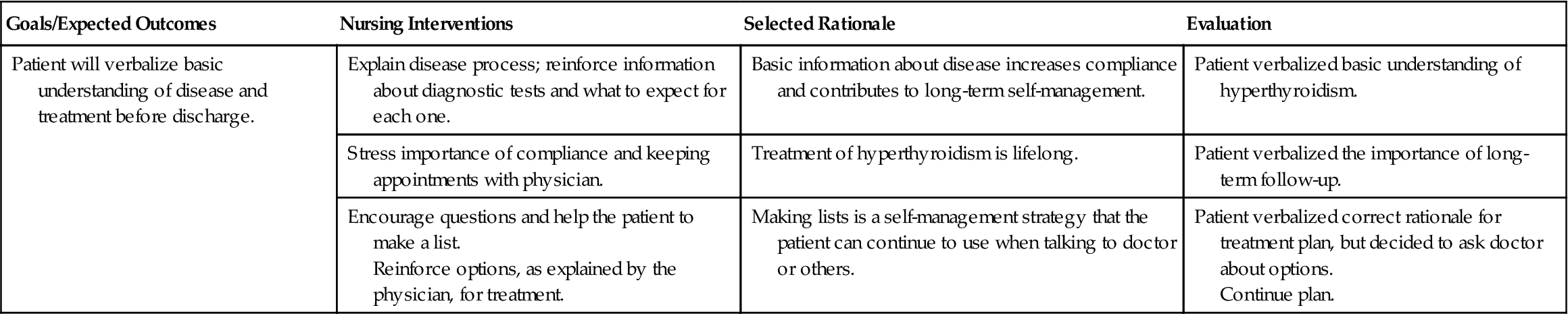

The excessive secretion of growth hormone caused by pituitary adenoma results in gigantism in children, leading to excessively tall stature, as the bone growth plates have not yet closed. In adults the result is acromegaly, and the adult’s facial features change: the lips thicken, the nose enlarges, and the forehead develops a bulge (Figure 37-1). Also, the adult’s hands and feet become enlarged; the first sign may be that the patient’s shoes no longer fit. Muscle weakness may occur with acromegaly, and osteoporosis and joint pain are common.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of a pituitary tumor begins with a complete history and physical examination. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and high-resolution computed tomography (CT) with contrast media may be used to identify, localize, and determine the extent of the tumor. A thorough ophthalmologic examination will be performed to evaluate pressure on the optic chiasm or optic nerves.

Treatment

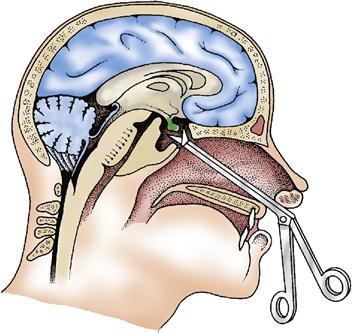

In some cases the physician may choose to treat the pituitary tumor conservatively with hormone therapy designed to reduce levels of growth hormone. If the tumor continues to grow or presents serious hormonal imbalances, it may be treated surgically or by irradiation. Some specialists prefer to remove the pituitary tumor surgically and then apply radiation to the site to be sure that all tumor cells have been destroyed. Hypophysectomy, or removal of the pituitary gland, is the surgical procedure, most often done microsurgically. The usual approach is transsphenoidal via the nose (Figure 37-2).

Nursing Management

After the surgery, the patient is kept in a semi-Fowler’s position. The nurse must closely monitor vital signs and the patient’s neurologic status. It is important to note and communicate promptly any change in vision, mental status, level of consciousness, or strength. The nurse must also monitor for any complications, such as diabetes insipidus (see p. 835). A nasal drip pad is in place and is changed as needed. Because nasal packing will be in place for 2 to 3 days, the patient must breathe through the mouth. After surgery it is important that the patient not brush his teeth, cough, sneeze, blow his nose, or bend forward, as these may interfere with the healing process. The nurse assists the patient with mouth rinses and encourages hourly deep-breathing exercises to prevent pulmonary problems.

Hypofunction of the pituitary gland

Hypofunction of the pituitary gland is a rare disorder characterized by a decrease in the level of one or more of the pituitary hormones.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The most common cause of pituitary hypofunction is a tumor. Other causes include autoimmune disorders, infections, or destruction of the pituitary. A rare but serious postpartum complication, Sheehan syndrome, involves infarction of the gland secondary to postpartum hemorrhage.

The most common pituitary hormone deficiency involves a decrease in the amount of GH and gonadotropins. This decrease results in metabolic problems and sexual dysfunction. Decrease in GH will lead to short stature in children; in adults it leads to an increase in bone breakdown, resulting in increased bone fragility and risk for osteoporosis. The decrease in gonadotropins may lead to testicular failure in a man and, ultimately, sterility. Ovarian failure, amenorrhea, and infertility occur with decreased gonadotropins in women.

Signs and Symptoms

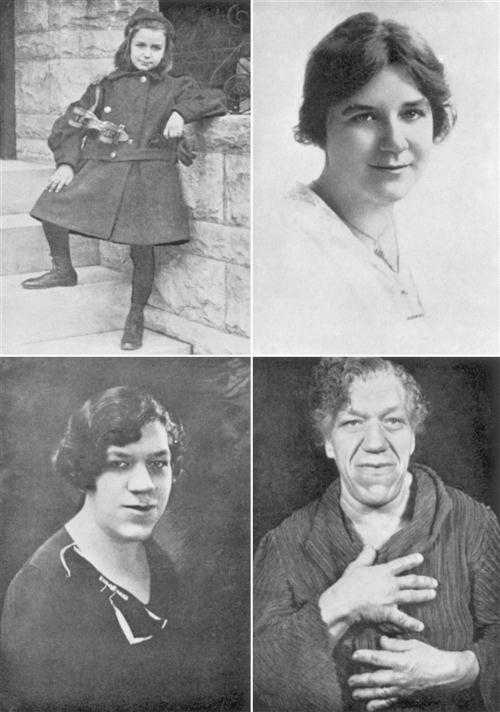

Signs and symptoms of pituitary hypofunction depend on the cause of pituitary failure and the hormones involved. If the disorder is related to a tumor, the patient may experience headaches, visual changes, anosmia (loss of the sense of smell), or seizures. Other signs and symptoms depend on the hormones decreased, and are outlined in Table 37-1.

Table 37-1

Decreased Hormones in Pituitary Hypofunction and Associated Clinical Manifestations

| Hormone Diminished | Associated Clinical Manifestations |

| Growth hormone (GH) | Decreased muscle mass, reduced strength, pathologic fractures |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH) | Women: Menstrual irregularities, diminished libido, decreased breast size |

| Men: Testicular atrophy, diminished spermatogenesis, loss of libido, impotence, decreased facial hair, decreased muscle mass | |

| Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), cortisol | Weakness, fatigue, headache, dry/pale skin, diminished axillary and pubic hair, postural hypotension, fasting hypoglycemia, decreased tolerance for stress, susceptibility to infection |

| Thyroid hormone | Similar to hypothyroidism, although milder: cold intolerance, constipation, fatigue, lethargy, weight gain |

Adapted from Lewis, S.L., Heitkemper, M.M., Dirksen, S.R., et al. (2011). Medical-Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems (8th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of pituitary gland hypofunction is made by history, physical examination, and diagnostic studies. Laboratory blood tests are performed to measure levels of pituitary hormones. MRI and CT are used to determine the presence or absence of a pituitary tumor.

Treatment and Nursing Management

The mainstay of treatment for hypofunction of the pituitary gland is lifelong replacement of the hormone(s) affected. Somatropin, via subcutaneous injection, is used to replace GH. The patient experiences a feeling of increased energy and well-being, although there are side effects, such as edema, joint pain, and headache. Gonadal hormone therapy is usually offered, including testosterone for men and estrogen/progesterone for women, although associated risks may outweigh the benefits for some patients. If the disorder is caused by a tumor, surgery or radiation for tumor removal is usually performed, followed by hormone therapy.

Nursing management involves recognizing the signs and symptoms of hypofunction of the pituitary. Teach the patient about lifelong hormone replacement therapy, including method and frequency of hormone replacements, side effects, and follow-up.

Diabetes Insipidus

Etiology and Pathophysiology

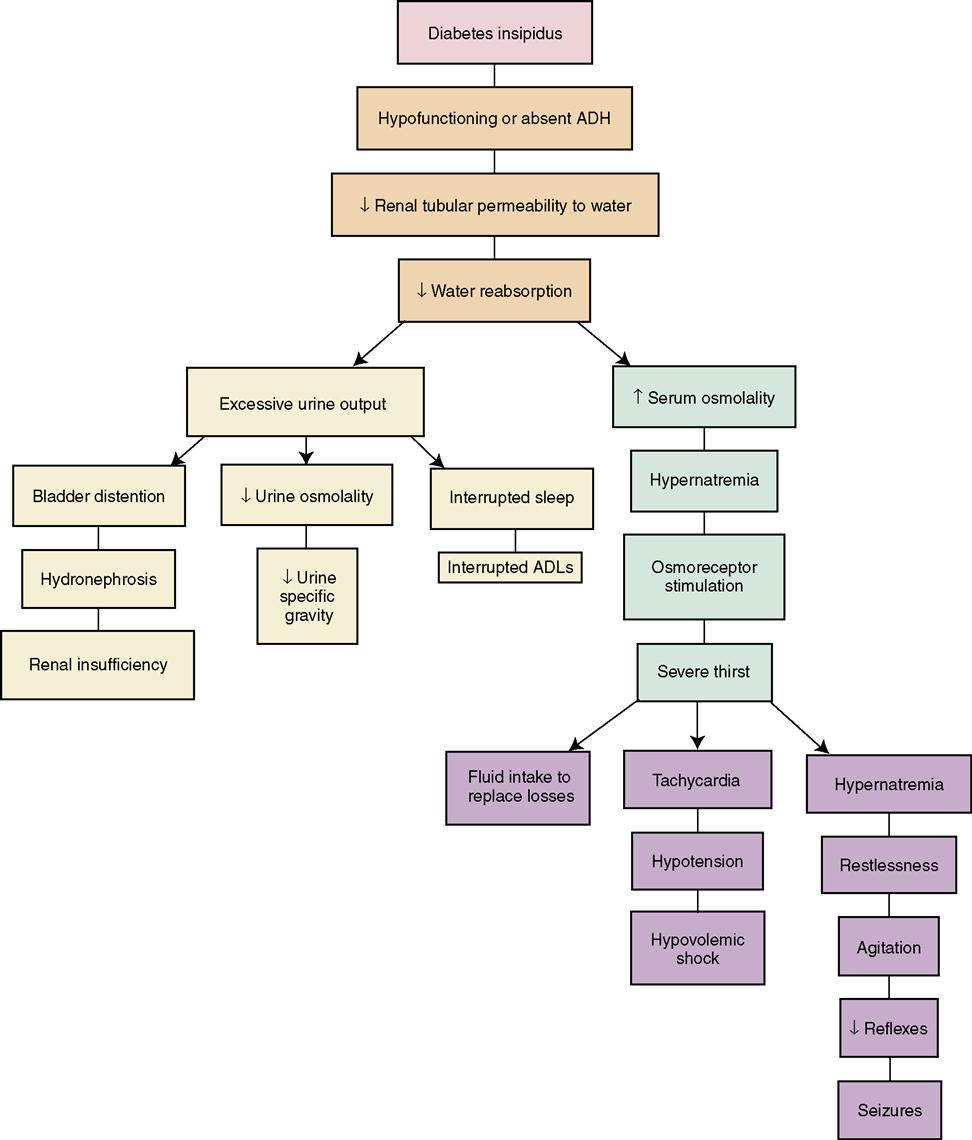

Diabetes insipidus (DI) is characterized by the production of copious amounts (usually more than 2.5 L/day) of dilute urine. DI results from decreased production of antidiuretic hormone (ADH), which regulates reabsorption of water in the kidney tubules. When ADH is not present in a sufficient amount, the water remains in the tubule and is excreted as urine (Concept Map 37-1). The following are three primary mechanisms of DI:

2. Nephrogenic DI, caused by drug therapy (lithium) or kidney disease

3. Dipsogenic DI, caused by excessive water intake (sometimes associated with schizophrenia)

Signs and Symptoms

The patient experiences profound diuresis (production of a large amount of urine), often as much as 15 to 20 L in every 24-hour period. Other signs and symptoms include thirst, weakness, and fatigue, often from nocturia (urination at night). The patient will exhibit signs of deficient fluid volume, such as tachycardia, hypotension, weight loss, constipation, and poor skin turgor. If untreated, the patient will demonstrate signs of shock and CNS manifestations progressing from irritability to eventual coma, resulting from hypernatremia and severe dehydration.

Diagnosis

To diagnose DI a complete history is obtained, and a physical examination and laboratory tests are performed, including urine and plasma osmolality, and urine specific gravity. A water deprivation test is done to confirm a suspected case of central DI.

Treatment and Nursing Management

Replacement of fluid and electrolytes, along with hormone therapy, represents the basis of treatment of DI. In central DI, the hormone of choice to replace insufficient ADH is desmopressin acetate (DDAVP), available orally, intravenously, or nasally. Other hormone medication choices exist, such as vasopressin (Pitressin) via nasal inhalation or by injection. For fluid replacement, hypertonic saline is used, titrated to match the patient’s urinary output.

Nursing management focuses on early detection, maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance, and patient education. Baseline vital signs and weight are important to accurately document and monitor throughout therapy. Strict (hourly) intake and output are essential to correct fluid losses and to titrate hypertonic saline infusion.

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone

Etiology and Pathophysiology

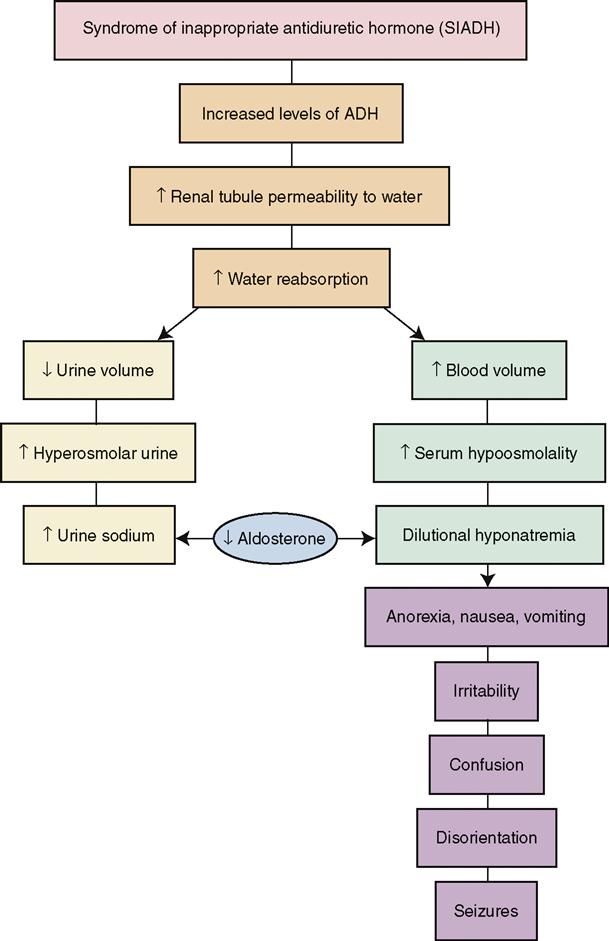

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) is the opposite of DI. Excessive amounts of ADH are produced, resulting in fluid retention (Concept Map 37-2). Numerous factors can cause SIADH, including malignancies and tumors pressing on the pituitary.

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of SIADH include confusion, seizure, and loss of consciousness accompanied by weight gain and edema. Hyponatremia from fluid excess is present with serum sodium often less than 120 mEq/L. As a result of the hyponatremia, the patient will experience muscle cramps and weakness. Urine output will be diminished.

Diagnosis

SIADH is diagnosed by performing urine and serum osmolality tests simultaneously. Results will demonstrate a decreased serum osmolality (less than 280 mOsm/kg) and elevated urine osmolality (more than 100 mmol/kg), which indicates the inappropriate excretion of concentrated urine in the presence of a dilute serum. Other laboratory tests to support the diagnosis include a decrease in blood urea nitrogen (BUN), hemoglobin, hematocrit, and creatinine clearance, and elevated urine sodium.

Treatment and Nursing Management

Treatment of SIADH is aimed at correcting the underlying cause, restricting fluids to 500 to 1000 mL/day, and administering sodium chloride, diuretics, and demeclocycline (a tetracycline) to increase excretion of water. In 2009 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved tolvaptan (Samsca) for the treatment of hyponatremia in SIADH. Tolvaptan improves serum sodium levels within 8 hours; however, there is a danger of overcorrection and sodium levels need to be closely monitored. Hypertonic enemas may be prescribed to draw out excess water.

Thorough nursing assessment/data collection is essential to monitor treatment and prevent complications of SIADH. The nurse must closely focus on the cardiovascular and neurologic systems and remain alert to the possibility of fluid shifts. The nurse must promptly notify the physician of any change in level of consciousness. Electrolytes are monitored closely (as often as several times per day), and daily weights are measured.

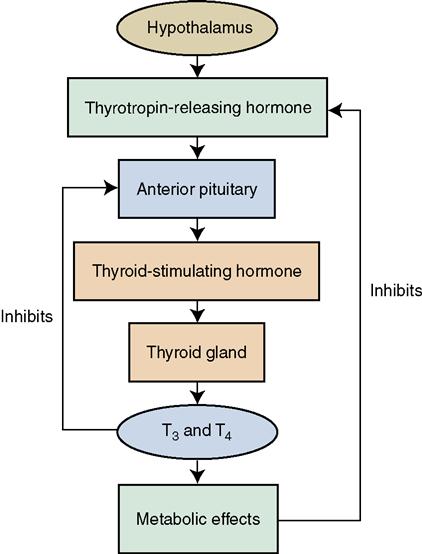

Disorders of the thyroid gland

Abnormalities in thyroid gland activity and resultant changes in the levels of thyroid hormones are among the most common disorders affecting the endocrine system. The thyroid gland secretes the hormones thyroxine (T4), triiodothyronine (T3), and thyrocalcitonin (see Chapter 36). The secretion of thyroid hormones is regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid control system (Concept Map 37-3). In other words, all three organs are involved in the closed-loop negative feedback system. Internal conditions, such as low thyroid and norepinephrine (NE) serum levels, can activate the hypothalamus, as can external conditions, such as cold. In response to feedback received by the hypothalamus, thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) is secreted. TRH acts on the pituitary gland, bringing about its release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). The TSH then acts on the thyroid cells, causing them to release thyroid hormones. When sufficient heat has been produced by increased metabolic activities (if cold was the stimulus), or when there are sufficient levels of thyroid hormone in the body fluids (if a deficit was the stimulus), feedback to the hypothalamus causes it to stop releasing TRH.

Goiter

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The person with a goiter has a greatly enlarged thyroid gland (Figure 37-3). The serum levels of the thyroid hormones may or may not be within normal limits. One type of goiter is caused by a deficiency of iodine in the diet. Iodine deficiency can be prevented by increasing iodine intake—for example, by using iodized salt. Although the administration of iodine will not cure goiter, it will stop the continued enlargement of the gland.

Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

Because there may be no systemic symptoms or changes in the metabolic rate of a person with simple goiter, the first sign that is usually noticed is an enlargement in the front of the neck. Later, if the gland continues to grow bigger, it presses against the esophagus and causes some difficulty in swallowing. The goiter also can press against the trachea and interfere with normal breathing. The diagnosis of goiter is established by history and physical examination. Goiter can be associated with increased, normal, or decreased hormone production.

Treatment

If goiter resulting from iodine deficiency is treated early, the growth of the gland can be arrested, and in some cases the enlargement will eventually disappear. Medications prescribed include preparations containing elemental iodine (the iodide ion). A very large goiter that continues to grow and produces local symptoms of pressure—or one that presents the possibility of developing into a malignant growth or a toxic goiter—is surgically removed in a procedure similar to the one sometimes done for hyperthyroidism.

Nursing Management

Iodine preparations should be given well diluted and administered through a straw, as they can stain the teeth. Adverse effects of iodine preparations can include gastrointestinal upset, metallic taste, skin rashes, allergic reactions, and epigastric pain.

Hyperthyroidism

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Patients at greatest risk for hyperthyroidism are adult women between 30 and 50 years of age. Primary hyperthyroidism is the result of an abnormality of function involving the thyroid gland itself, and causes excessive circulation of thyroid T4 and T3 hormones. However, it is possible that only the T3 level will be above normal if the patient has Graves’ disease, toxic adenoma of the thyroid, or toxic nodular goiter.

High serum levels of T4 can be caused by either overactivity of the thyroid gland or by excessive doses of T4 given in replacement therapy. Primary hyperthyroidism is more common in women 30 to 50 years of age. Secondary hyperthyroidism usually is the result of an abnormality in another gland, such as the pituitary gland, that could produce too much TSH and therefore overstimulate the thyroid gland.

Primary hyperthyroidism is also known as Graves’ disease or toxic goiter. Medications containing iodine, such as amiodarone (an antidysrhythmic heart medication) can predispose to hyperthyroidism. In addition, it has been discovered recently that women who smoke have nearly twice the risk of developing hyperthyroidism when compared with nonsmokers.

Signs and Symptoms

The earliest symptoms of hyperthyroidism may be weight loss (in spite of a good appetite) and nervousness. Symptoms can vary from mild to severe, and may include weakness, insomnia, tremulousness, agitation, tachycardia, palpitations, exertional dyspnea, ankle edema, difficulty concentrating, diarrhea, increased thirst and urination, decreased libido, scanty menstruation, and infertility. The condition sometimes is not diagnosed in its early stages because of the vagueness of the symptoms. In some cases hyperthyroidism is misdiagnosed as a cardiovascular disease, as symptoms are similar.

If hyperthyroidism is not diagnosed correctly and continues untreated for any length of time, the patient can develop true organic heart disease and may experience myocardial infarction.

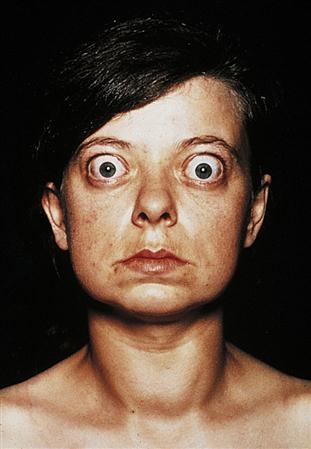

The symptoms manifested by a hyperthyroid patient are the result of an accelerated metabolic rate and a speeding up of all physiologic processes. Emotional upheaval occurs as a result of the action of thyroid hormones on the nervous system. The patient often reports episodes of emotional extremes with uncontrollable crying and depression followed by intense physical activity and euphoria. The patient with hyperthyroidism also exhibits an enlarged thyroid gland (toxic goiter) and abnormal protrusion of the eyeballs, or exophthalmos (Figure 37-4).

Diagnosis

Medical diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations of hyperthyroidism and the results of laboratory tests for thyroid hormone levels. One indicator of hyperthyroidism is assessment of the heart rate while the patient is sleeping. A rate that is consistently above 80 could signify a toxic state resulting from excessive levels of thyroid hormone. The physician may also order an electrocardiogram (ECG) to evaluate cardiac dysrhthymias or a CT or MRI to rule out ocular complications.

Treatment and Nursing Management

Hyperthyroidism may be treated medically by administering radioactive iodine and antithyroid drugs, mild sedatives, and beta-adrenergic blocking agents to control tremor, temperature elevation, restlessness, and tachycardia. Radioactive iodine (131I), also known as ablation therapy, is the definitive treatment for hyperthyroidism. It is contraindicated in pregnant and nursing women, as it can disable the infant’s thyroid gland. The main disadvantage of ablation therapy is the possibility of hypothyroidism (deficient activity of the thyroid gland) caused by “overeffective” treatment. The hypothyroidism can occur immediately after treatment or long after it is completed; thus the patient must have ongoing follow-up.

Dosage depends on the size of the gland and the thyroid’s sensitivity to radiation. Patients receiving small doses can be given the drug orally for several doses on an outpatient basis. Larger doses require isolation of the patient for 8 days, which is the half-life (the time required for half the nuclei to undergo radioactive decay) of 131I.

Because the iodine circulates in the blood and is excreted by the kidneys, precautions must be taken when handling needles, syringes, and other equipment likely to be contaminated with blood, and bedpans, urinals, and specimen bottles likely to be contaminated by urine.

All patients receiving radioactive iodine must be observed for signs of thyroid crisis resulting from radiation-induced thyroiditis (discussed later). If hyperthyroidism is not controlled within several months of therapy with radioactive iodine alone, the patient will require adjunctive therapy in the form of potassium iodide and antithyroid drugs.

Antithyroid drugs are prescribed as the initial treatment of hyperthyroidism in children, young adults, and pregnant women. Methimazole (Tapazole) is the main drug used. The patient must take the antithyroid drug at the prescribed time and strictly according to schedule. Iodine preparations such as propylthiouracil (PTU) and potassium iodide (SSKI) have only a temporary effect.

Iodine preparations also may be given for a period of 10 to 14 days before surgery of the thyroid to reduce the vascularity of the gland, minimizing the danger of releasing large amounts of thyroid hormone into the bloodstream during surgery, and to decrease the risk of hemorrhage.

Thyroidectomy

Patients who do not respond well to antithyroid drug therapy, who are unable to take radioactive iodine, or who have greatly enlarged thyroid glands are candidates for a subtotal thyroidectomy. Patients with thyroid malignancy undergo a total thyroidectomy. In the subtotal procedure, two thirds of the glandular mass is removed. The remaining portion of the gland is left intact so production and release of thyroid hormones can continue. For most patients, however, surgery is a treatment of last resort, as the potential complications of hemorrhage, hypoparathyroidism, and vocal cord paralysis can be emotionally devastating. Many patients will be rendered hypothyroidic because of surgery or radiation therapy that alters thyroid function. It is then necessary to manage their illness with long-term thyroid replacement therapy.

Because many of the signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism mimic those of cardiac disease, the nurse caring for the older adult must be alert to the possibility that such signs may be indicative of an endocrine, rather than a cardiac, disorder. Physical and mental rest is extremely important, because physical stress and emotional upset can stimulate greater activity in the thyroid gland. Adequate rest is essential to conserve strength, but it is difficult for a person with hyperthyroidism to relax and get sufficient rest.

The diet of the patient with hyperthyroidism should be sufficiently high in calories to meet metabolic needs. This will vary from person to person, but continued loss of weight is an indication that more high-calorie foods are needed. It may be necessary to refer the patient to a dietitian, who can work out a satisfactory diet that helps maintain normal body weight.

Patients who are being treated medically for hyperthyroidism must understand that they have an illness that requires ongoing medication and frequent monitoring to assess the effectiveness of treatment. Sometimes it is difficult for the patient’s family to accept and deal with the emotional outbursts and mood changes that are present when the disease is not under control. Once hormone levels return to the normal range, the mental and physical symptoms should subside.

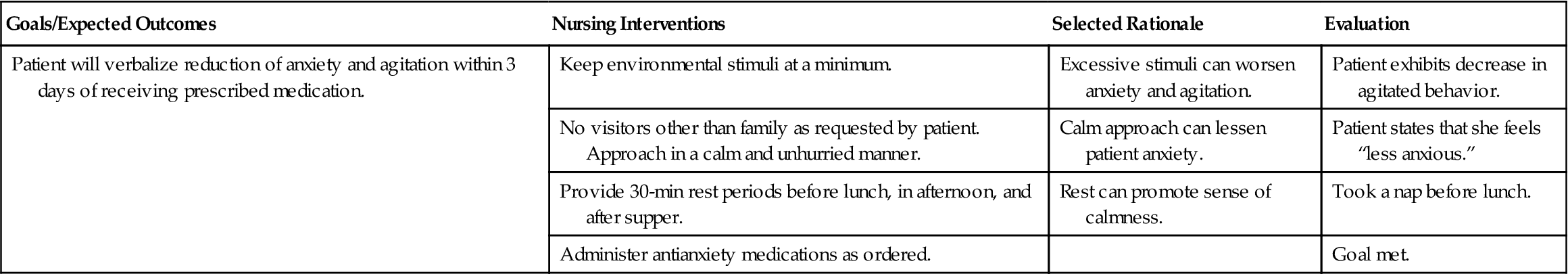

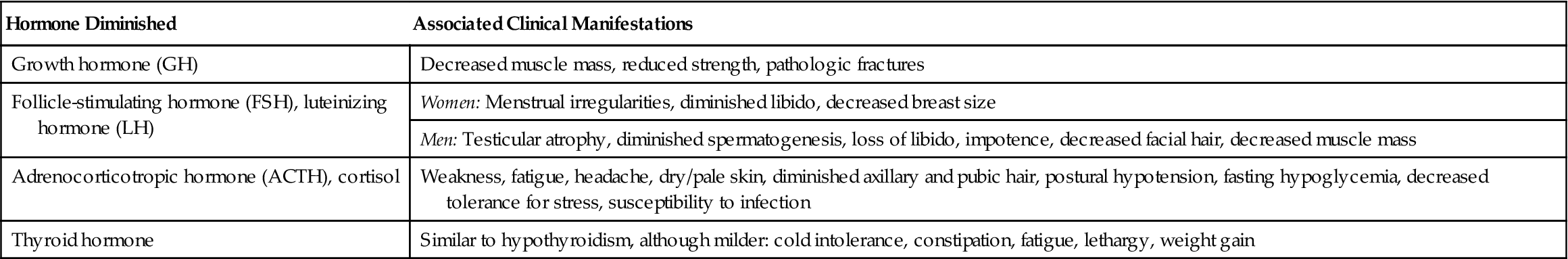

Nursing interventions for selected problems of patients with hyperthyroidism are summarized in Nursing Care Plan 37-1.

Nursing Care Plan 37-1

Nursing Care Plan 37-1