Drugs Used to Treat Gastroesophageal Reflux and Peptic Ulcer Disease

Objectives

1 Describe the physiology of the stomach.

2 Cite common stomach disorders that require drug therapy.

4 Discuss the drug classifications and actions used to treat stomach disorders.

Key Terms

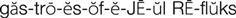

parietal cells ( ) (p. 519)

) (p. 519)

hydrochloric acid ( ) (p. 519)

) (p. 519)

gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) ( ) (p. 519)

) (p. 519)

heartburn ( ) (p. 519)

) (p. 519)

peptic ulcer disease (PUD) ( ) (p. 520)

) (p. 520)

Helicobacter pylori ( ) (p. 520)

) (p. 520)

Physiology of the Stomach

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

As a major part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the stomach has three primary functions: (1) storing food until it can be processed in the lower GI tract; (2) mixing food with gastric secretions until it is a partially digested, semisolid mixture known as chyme; and (3) slowly emptying the stomach at a rate that allows proper digestion and absorption of nutrients and medicine from the small intestine.

Three types of secretory cells line portions of the stomach—chief, parietal, and mucus cells. The chief cells secrete pepsinogen, an inactive enzyme. Parietal cells are stimulated by acetylcholine from cholinergic nerve fibers, gastrin, and histamine to secrete hydrochloric acid, which activates pepsinogen to pepsin and provides the optimal pH for pepsin to start protein digestion. Normal pH in the stomach ranges from 1 to 5, depending on the presence of food and medications. Hydrochloric acid also breaks down muscle fibers and connective tissue ingested as food and kills bacteria that enter the digestive tract through the mouth. The parietal cells also secrete intrinsic factor needed for absorption of vitamin B12. The mucus cells secrete mucus, which coats the stomach wall. The 1-mm-thick coat is alkaline and protects the stomach wall from damage by hydrochloric acid and the digestive enzyme pepsin. It also contributes lubrication for food transport. Small amounts of other enzymes are also secreted in the stomach. Lipases digest fats, and gastric amylase digests carbohydrates. Other digestive enzymes are also carried into the stomach from swallowed saliva.

Prostaglandins play a major role in protecting the stomach walls from injury by stomach acids and enzymes. Prostaglandins are produced by cells lining the stomach and prevent injury by inhibiting gastric acid secretion, maintaining blood flow, and stimulating mucus and bicarbonate production.

Common Stomach Disorders

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), more commonly referred to as heartburn, acid indigestion, or sour stomach, is a common stomach disorder. Approximately one third of the U.S. population experiences heartburn once each month, and 5% to 7% have heartburn daily. Common symptoms are a burning sensation, bloating, belching, and regurgitation. Other symptoms that are reported less frequently are nausea, a “lump in the throat,” hiccups, and chest pain.

GERD is the reflux of gastric secretions, primarily pepsin and hydrochloric acid, up into the esophagus. Causes of GERD are a weakened lower esophageal sphincter, delayed gastric emptying, hiatal hernia, obesity, overeating, tight-fitting clothing, and increased acid secretion. Acid secretions are increased by smoking, alcohol, carbonated beverages, coffee, and spicy foods.

Most cases of GERD pass quickly with only mild discomfort, but frequent or prolonged bouts of acid reflux cause inflammation, tissue erosion, and ulcerations in the lower esophagus. Anyone who has recurrent or continuous symptoms of reflux, especially if the symptoms interfere with activities, should be referred to a health care provider. These symptoms may also accompany more serious conditions, such as ischemic heart disease, scleroderma, and gastric malignancy.

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) refers to several stomach disorders that result from an imbalance between acidic stomach contents and the body’s normal defense barriers, causing ulcerations in the GI tract. The most common illnesses are gastric and duodenal ulcers. It is estimated that approximately 10% of all Americans will develop an ulcer at some time in their lives. The incidence in men and women is approximately the same. Race, economic status, and psychological stress do not correlate with the frequency of ulcer disease. Often, the only symptom reported is epigastric pain, described as burning, gnawing, or aching. Patients often report that varying degrees of pain are present for a few weeks and are then gone, only to recur a few weeks later. The pain is most often noted when the stomach is empty, such as at night or between meals, and is relieved by food or antacids. Other symptoms that cause patients to seek medical attention are bloating, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia.

Ulcers appear to be caused by a combination of acid and a breakdown in the body’s defense mechanisms that protect the stomach wall. Proposed mechanisms are oversecretion of hydrochloric acid by excessive numbers of parietal cells, injury to the mucosal barrier such as that resulting from prostaglandin inhibitors (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], including aspirin), and infection of the mucosal wall by Helicobacter pylori. It had been thought that no bacterium could survive in the highly acidic environment of the stomach; however, H. pylori was first isolated from patients with gastritis in 1983. The bacterium seems able to live below the mucus barrier, where it is protected from stomach acid and pepsin. H. pylori is now thought to be associated with as many as 90% of duodenal and 70% of gastric ulcers. The exact mechanism whereby H. pylori contributes to ulcer formation is not known, but several hypotheses are being tested.

Several risk factors increase the likelihood of peptic ulcer disease:

Goals of Treatment

The goals of treatment of GERD are to relieve symptoms, decrease the frequency and duration of reflux, heal tissue injury, and prevent recurrence. The most important treatment is a change in lifestyle, which includes losing weight (if significantly over the ideal body weight), reducing or avoiding foods and beverages that increase acid production, reducing or stopping smoking, avoiding alcohol, and consuming smaller meals. Additional therapy includes remaining upright for 2 hours after meals, not eating before bedtime, and avoiding tight clothing over the abdominal area. Lozenges may be used to increase saliva production, and antacids and alginic acid therapy may provide relief for patients who experience infrequent heartburn. If the patient’s symptoms do not improve within 2 to 3 weeks, or if the condition is severe, additional pharmacologic measures should be tried to reduce irritation. About 5% to 10% of patients with GERD require surgery.

The treatment of PUD and GERD is somewhat similar: relieve symptoms, promote healing, and prevent recurrence. Lifestyle changes that eliminate risk factors, such as cigarette smoking and foods (and alcohol) that increase acid secretion, should be initiated. Patients rarely need to be restricted to a bland diet. If NSAIDs are being taken, consideration should be given to switching to acetaminophen if feasible. For decades, ulcer treatment focused on reducing acid secretions (anticholinergic agents, H2 antagonists, gastric acid pump inhibitors), neutralizing acid (antacids), or coating ulcer craters to hasten healing (sucralfate). Major changes in therapy have come about because the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved antibiotics to eradicate H. pylori. Several large studies are under way to refine the healing and reduce ulcer recurrence rate. Various combinations of antimicrobial agents (e.g., amoxicillin, tetracycline, metronidazole, clarithromycin), bismuth, and antisecretory agents (e.g., H2 antagonists, proton pump inhibitors) are used to eradicate H. pylori. Antibiotics are not recommended for individuals who are asymptomatic with H. pylori because there is concern that resistant strains of bacteria may develop.

Drug Therapy

Actions

Uses

Nursing Implications for Agents Used for Stomach Disorders

Nursing Implications for Agents Used for Stomach Disorders

Assessment

Nutritional Assessment.

Obtain patient data about current height, weight, and any recent weight gain or loss. Identify the normal pattern of eating, including snacking habits. Use a food guide such as MyPlate (see Figure 47-1) as a guide when asking questions to identify the usual foods eaten by the individual. Ask about any nutritional or cultural restrictions associated with dietary practices. Are there any food allergies (obtain details), or foods that particularly cause gastric distress when eaten? Does the individual take any nutritional supplements? How often and how much fast food is eaten?

Esophagus, Stomach.

Ask patients to describe symptoms. Question in detail what is meant by the terms indigestion, heartburn, upset stomach, nausea, and belching.

Pain, Discomfort

Activity, Exercise.

Ask specifically what type of work or activities the individual performs that may increase intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., lifting heavy objects, bending over frequently).

History of Diseases or Disorders

Medication History

Anxiety or Stress Level.

Ask the patient to describe his or her lifestyle. What does the patient think are stressors, and how often do they occur?

Smoking.

What is the frequency of smoking?

Implementation

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Nutrition

Pain, Discomfort.

Keep a written record of the onset, duration, location, and precipitating factors for any pain. Sit upright at the table when eating and do not lie down for at least 2 hours after eating. When a hiatal hernia is present, elevate the head of the bed on 6- to 8-inch blocks to prevent reflux during sleep. Have the patient keep a log of the pain including time of day, any factors that might have precipitated the pain, and degree of pain relief from medications used.

Medications

Lifestyle Changes

Fostering Health Maintenance

Written Record.

Enlist the patient’s aid in developing and maintaining a written record of monitoring parameters (e.g., a list of foods causing problems, degree of pain relief) (see Patient Self-Assessment form for Agents Affecting the Digestive System on the Evolve Web site ![]() at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton). Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions prescribed.

at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton). Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions prescribed.

Drug Class: Antacids

Actions

Antacids lower the acidity of gastric secretions by buffering the hydrochloric acid (normal pH is 1 to 2) to a lower hydrogen ion concentration. Buffering hydrochloric acid to a pH of 3 to 4 is highly desired because the proteolytic action of pepsin is reduced and the gastric juice loses its corrosive effect.

Uses

Antacid products account for one of the largest sales volumes (more than $1 billion annually) of over-the-counter medication. Antacids are commonly used for heartburn, excessive eating and drinking, and PUD. However, nurses and patients must be aware that not all antacids are alike. They should be used judiciously, particularly by certain types of patients (e.g., those with heart failure, hypertension, renal failure). Long-term self-treatment with antacids may also mask symptoms of serious underlying diseases, such as a bleeding ulcer.

The most effective antacids available are combinations of aluminum hydroxide, magnesium oxide or hydroxide, magnesium trisilicate, and calcium carbonate. All act by neutralizing gastric acid. Combinations of these ingredients must be used because any compound used alone in therapeutic quantities may produce severe systemic adverse effects. Other ingredients found in antacid combination products include simethicone, alginic acid, and bismuth. Simethicone is a defoaming agent that breaks up gas bubbles in the stomach, reducing stomach distention and heartburn. It is effective in patients who have overeaten or who have heartburn, but it is not effective in treating PUD. Alginic acid produces a highly viscous solution of sodium alginate that floats on top of the gastric contents. It may be effective only for the patient being treated for GERD or hiatal hernia and should not be used in the patient with acute gastritis or PUD. Bismuth compounds have little acid-neutralizing capacity and are therefore poor antacids.

The following principles should be considered when antacid therapy is planned:

Therapeutic Outcomes

The primary therapeutic outcomes expected from antacid therapy are relief of discomfort, reduced frequency of heartburn, and healing of irritated tissues.

Nursing Implications for Antacids

Nursing Implications for Antacids

Premedication Assessment

Availability

See Table 33-1.

![]() Table 33-1

Table 33-1

Ingredients of Commonly Used Antacids

| PRODUCT | FORM | CALCIUM CARBONATE | ALUMINUM HYDROXIDE | MAGNESIUM OXIDE OR HYDROXIDE | SODIUM BICARBONATE | SIMETHICONE | OTHER INGREDIENTS |

| Aludrox | Tablet, suspension | — | X | X | — | X | — |

| Baking soda | Powder | — | — | — | X | — | — |

| Di-Gel | Tablet, liquid | — | X | X | — | X | — |

| Gelusil | Tablet | — | X | X | — | X | — |

| Maalox Maximum Strength | Suspension | — | X | X | — | X | — |

| Mylanta | Tablet, suspension | — | X | X | — | X | — |

| Mylanta Extra Strength | Suspension | — | X | X | — | X | — |

| Mylanta Supreme | Liquid | X | — | X | — | — | — |

| Phillip’s Milk of Magnesia | Tablet, suspension | — | — | X | — | — | — |

| Riopan | Suspension | — | — | — | — | — | Magaldrate |

| Riopan Plus | Tablet, suspension | — | — | — | — | X | Magaldrate |

| Titralac Plus | Tablet, suspension | X | — | — | — | X | — |

| Tums | Tablet | X | — | — | — | — | — |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree