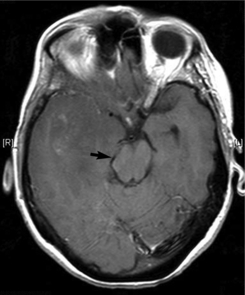

Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) can be caused by numerous surgical and medical problems. The skull is a closed compartment, therefore an increase in volume can lead to symptoms of ICP. The skull contains the brain and interstitial fluid, intravascular blood, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The Monro-Kellie hypothesis states that if one component increases in volume, another component must decrease in volume to maintain homeostasis (Goetz, 2003). The ICP is ever changing and is affected by several physiologic processes. A common cause of increased ICP is a malignant intracranial process. Malignant processes can increase pressure through displacement of brain tissue, obstruction of CSF flow, and increased vascularity associated with tumor growth (Fig. 32.1). Increased ICP often is an early sign of a progressive tumor, and increased ICP can quickly lead to life-threatening complications.

|

| Fig. 32.1Subfalcine herniation (arrow) caused by progressive right temporal brain tumor. |

Increased ICP produces several warning symptoms, including papilledema, headaches, nausea and vomiting, vital sign changes, and neurologic dysfunction, depending on the location of the tumor and edema. Papilledema occurs secondary to tumor blockage of the CSF flow, which increases pressure around the optic nerve. Subsequently, venous blood outflow becomes impaired, which causes edema of the optic disk. Papilledema is almost always bilateral and does not affect vision. It may occur over several hours or several days, depending on the etiology (Greenberg et al., 1993).

Headache is another common presenting symptom of increased ICP. It usually is marked by an early morning onset of bilateral frontal or occipital pain. The pain is exacerbated by movements that increase ICP, such as lying down, bending over, coughing, and/or the Valsalva maneuver. The headache may be accompanied by projectile vomiting as a result of increased pressure on the vomiting center in the medulla oblongata. It is thought that headache pain occurs secondary to pressure exerted by the tumor on the large blood vessels and dura and on the cranial and cervical nerve fibers (Dalessio, 1978).

Patients may also develop Cushing’s triad, a set of three clinical manifestations (i.e., bradycardia, systolic hypertension, and widening pulse pressure) caused by direct pressure and/or tumor invasion into the vasomotor center in the medulla. These signs, which may occur in response to intracranial hypertension or herniation syndrome, are a late finding of neurologic deterioration (Carlson, 2002). Other focal symptoms are possible and are directly related to the location of the tumor. These may include hemiparesis, aphasia, seizures, hemisensory loss, and/or personality changes.

Primary brain tumors account for only 1.3% of all cancers (ACS, 2006), but they often present with symptoms of increased ICP. Low-grade tumors grow slowly, therefore the intracranial pressure increases slowly, which may not always lead to symptom development. High-grade tumors, primarily glioblastoma multiforme, grow rapidly, leading to acute onset of symptoms such as headache, hemiparesis, seizures, visual changes, and aphasia, depending on the tumor’s location. Some tumors can cause acute blockage of CSF flow through the ventricles, resulting in a dramatic increase in ICP. Regardless of the cause, the increased pressure in the intracranial cavity can cause nerve cell damage and death.

The treatment for increased ICP includes procedures and pharmacologic approaches. Emergency placement of a ventriculostomy catheter through a burr hole is performed to reduce the ICP immediately by draining CSF fluid. This allows for close management and monitoring of CSF drainage. Surgical resection or debulking of malignant tissue can also alleviate ICP relatively quickly. Chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy is used to reduce the tumor burden, resulting in decreased ICP. These options are beneficial for patients who are not eligible for surgery because of the tumor’s location or because of poor performance status.

Pharmacologic approaches to the management of ICP include osmotic diuretics, glucocorticoids, barbiturate therapy, and/or anticonvulsants. Mannitol, an osmotic diuretic, pulls fluid from the interstitial space into the vascular space. To prevent fluid overload in the vasculature, a loop diuretic may be administered (LeJeune & Howard-Fain, 2002). Glucocorticoids are most helpful for managing increased ICP secondary to intracranial or spinal cord malignancies (LeJeune, & Howard-Fain, 2002). Barbiturate therapy is used to lower cerebral blood flow and brain metabolism, which can lower the ICP; however, this may lead to hypotension, therefore caution should be used. Anticonvulsants are used to prevent seizure activity. It is critical that oncology nurses be alert for signs of increased ICP and its management so that emergency interventions can be initiated to reduce damage.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY

Patients with cancer can develop increased ICP from primary brain tumors, brain metastases, hemorrhage, meningitis, head trauma, infarction, or abscess (Quinn & DeAngelis, 2000). The onset can be acute or subacute. Cerebrovascular disease, specifically infarction and/or hemorrhage, is the most common etiology of neurologic symptoms in patients with cancer. One study found that 14.6% of 3426 patients with terminal cancer had cerebral hemorrhages or infarctions (Graus et al., 1985). Coagulation disorders, infection, cerebral metastases, and complications from cancer treatment are the most common causes of cerebrovascular disease in patients with cancer (Graus et al., 1985).

RISK PROFILE

• Cancer, especially primary gliomas, brain metastases, neuroblastomas, and leukemia. Primary cancers with an increased incidence of brain metastases include lung cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma

• Pediatric brain tumors, including cerebellar tumors, medulloblastoma, and ependymoma of the fourth ventricle

• Coagulation disorder, thrombocytopenia, or platelet dysfunction

• Bacterial or fungal infection, meningitis, or brain abscess

• Head trauma

• Previous whole brain or focal radiation therapy over 6000 cGy or radiosurgery

• Hydrocephalus

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis varies and can depend on whether the condition is rapidly diagnosed and treated. Compensatory mechanisms control the ICP, but these eventually fail. As the pressure increases, critical brain structures are compromised, including the brainstem. If left untreated, the increasing cerebral edema leads to ischemia, followed by coma and subsequently death. Treatment includes:

• Removal of the tumor

• Radiation therapy

• Shunt placement

• Chemotherapy

PROFESSIONAL ASSESSMENT CRITERIA (PAC)

1. Baseline neurologic exam, including:

• Orientation: Person, place, and time.

• Level of consciousness (LOC): Agitation, confusion, restlessness, lethargy.

• Muscle strength: Hemiparesis, flexion, dorsiflexion, pronator drift, coordination.

• Vital signs: Widened pulse pressure, irregular respirations, bradycardia secondary to pressure on the vasomotor centers of the medulla.

• Pupillary response: Size and shape, equal and reactive to light.

2. Early signs and symptoms (Table 32-1):

• Headaches

• Nausea secondary to pressure on the medulla.

• Projectile vomiting secondary to pressure on the vomiting center of the medulla.

• Hemiparesis

• Unilateral pupil dilation with slow reaction.

• Changes in LOC, including restlessness, agitation, and/or confusion.

| Early Symptoms | Late Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Headaches | Change in the level of consciousness, including stupor and coma |

| Nausea | Worsening headache |

| Projectile vomiting | Abnormal motor functioning, including decorticate/decerebrate posturing |

| Hemiparesis | Cushing’s triad (elevated BP, widening pulse pressure, and bradycardia) |

| Unilateral pupil dilation with slow reaction | Pupils dilated and fixed bilaterally |

| Visual disturbances, including blurred vision, diplopia, and decreased visual acuity | Papilledema |

3. Late signs and symptoms (see Table 32-1):

• Change in LOC: Stupor, coma.

• Worsening headache.

• Motor function: Decorticate/decerebrate posturing.

• Cushing’s triad: Bradycardia, systolic hypertension, and widening pulse pressure.

• Pupils dilated and fixed bilaterally.

• Papilledema: An increase in the ICP leads to increased pressure on the optic nerve; this impairs the outflow of blood, causing edema of the optic disk.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access