Care of Patients with Disorders of the Lower Gastrointestinal System

Objectives

1. Compare the etiology and signs and symptoms of various types of hernias.

2. Discuss the characteristics of irritable bowel syndrome.

3. Explain how diverticulitis occurs.

4. Illustrate how the two types of intestinal obstruction occur and the symptoms.

6. Identify types of patients who are at risk for peritonitis.

7. Plan nursing interventions for the patient having surgery of the lower intestine and rectum.

8. Discuss ways to help the patient psychologically adjust to having an ostomy.

9. Compare the characteristics of hemorrhoids, pilonidal sinus, and anorectal fistula.

1. Choose nursing interventions for the patient with inflammatory bowel disease.

2. Assess for the signs and symptoms of appendicitis.

3. Differentiate the signs and symptoms of appendicitis from peritonitis.

4. Create a teaching plan for the prevention of colorectal cancer.

5. Write a nursing care plan for the patient with cancer of the colon and intestinal obstruction.

7. Observe the equipment and procedure for changing an ostomy appliance.

Key Terms

anastomosis (ă-năs-tō-MŌ-sĭs, p. 675)

colectomy (kŏ-LĔK-tō-mē, p. 675)

colostomy (kŏ-LŎS-tō-mē, p. 675)

cryotherapy (krī-ō-THĔR-ă-pē, p. 686)

diverticulitis (dī-vĕr-tĭk-ū-LĪ-tĭs, p. 668)

diverticulosis (dī-vĕr-tĭk-ū-LŌ-sĭs, p. 665)

diverticulum (dī-vĕr-TĬK-ū-lŭm, p. 665)

hemicolectomy (hĕ-mē-kŏ-LĔK-tō-mē, p. 675)

hemorrhoidectomy (HĔM-rŏyd-ĔK-tō-mē, p. 686)

hemorrhoids (HĔM-rŏydz, p. 685)

hernia (HĔR-nē-ă, p. 663)

hernioplasty (hĕr-nē-ŏ-PLĂS-tē, p. 664)

herniorrhaphy (hĕr-nē-ŎR-ĕ-fē, p. 664)

ileostomy (ĭl-ē-ŎS-tō-mē, p. 680)

intussusception (ĭn-tŭs-sŭs-SĔP-shŭn, p. 668)

lysed (līzd, p. 669)

mucorrhea (mū-kō-RĒ-ă, p. 665)

paralytic ileus (păr-ă-LĬT-ĭk ĬL-ē-ŭs, p. 669)

peritonitis (pĕr-ĭ-tō-NĪ-tĭs, p. 673)

photocoagulation (fō-tō-kō-ăg-ū-LĀ-shŭn, p. 686)

pilonidal (pī-lō-NĪ-dăl, p. 686)

scleropathy (sklĕr-ō-pă-thē, p. 686)

steatorrhea (stĕ-ă-tō-RĒ-ă, p. 674)

volvulus (VŎL-vū-lŭs, p. 668)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Disorders of the Abdomen and Bowel

Abdominal and Inguinal Hernia

Etiology and Pathophysiology

If there is a defect in the muscular wall of the abdomen, the intestine may break through the defect. This protrusion is called a hernia or a rupture.

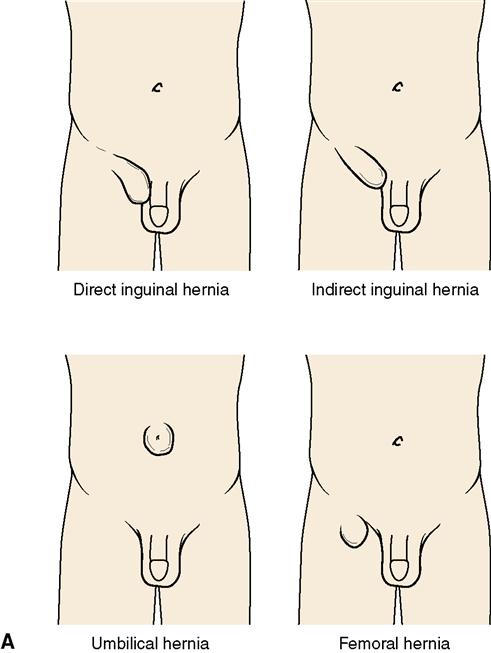

The most common locations for a hernia are in areas where the abdominal wall is normally weaker and more likely to allow a segment of intestine to protrude (Figure 30-1). These include the center of the abdomen at the site of the umbilicus and the lower abdomen at the points where the inguinal ring and the femoral canal begin. The most common contributing factors in the development of a hernia are straining to lift heavy objects, chronic cough, straining to void or pass stool, and ascites. Inguinal hernias are more common in men. A hernia may form at an old abdominal surgical incision.

Hernias are classified as reducible, which means the protruding organ can be returned to its proper place by pressing on the organ, and irreducible or incarcerated, which means that the protruding part of the organ is tightly wedged outside the cavity and cannot be pushed back through the opening. If the protruding part of the organ is not replaced and its blood supply is cut off, the hernia is said to be strangulated. An indirect hernia protrudes through the inguinal ring. A direct hernia protrudes through the posterior inguinal wall.

Signs and Symptoms

If the hernia is not incarcerated, there will just be an abnormal pouching, a “lump” or local swelling out from the abdominal wall or in the groin area (inguinal hernia). When pressure on the abdominal wall is removed by lying down, the swelling disappears. Lifting of heavy objects, coughing, or any activity that puts a strain on the abdominal muscles may force the organ back through the opening, and the swelling reappears.

Some discomfort may accompany the hernia. Pain occurs when the peritoneum becomes irritated or when the hernia is incarcerated or strangulated. The flow of intestinal contents can be blocked by an incarcerated hernia, and cause symptoms of intestinal obstruction. This is an emergency because when the blood supply is restricted, part of the intestine may die.

Treatment

The surgical procedure used in the treatment of a hernia is called a herniorrhaphy, which means a surgical repair of a hernia. The defect is closed with sutures. If the area of weakness is very large, a hernioplasty is done. In this procedure, some type of strong synthetic material is sewn over the defect to reinforce the area. The procedure is now most often done on an outpatient basis.

Careful discharge instructions are given to the hernia patient to prevent respiratory problems because the patient should not cough in the immediate postoperative period. Guidelines on signs and symptoms of complications are sent home with the patient, along with a written list of activities to avoid until healing is complete.

If surgery is not possible because of age or poor surgical risk, the patient may be fitted with an appliance called a truss, which simply reinforces the weakened cavity wall and prevents protrusion of the intestines. The truss is put on in the morning before the patient gets out of bed, because the hernia is more likely to be reduced at that time. It is only a symptomatic measure and does not cure the hernia.

Nursing Management

Care after hernia repair is directed at pain control and preventing recurrence of the hernia. The patient is cautioned not to do heavy lifting, pulling, or pushing that increases intra-abdominal pressure. Postoperative care is similar to other surgical patients (see Chapter 5).

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional disorder of gastrointestinal motility. In the United States more people suffer with IBS than with diabetes or asthma and IBS is a major reason for missing workdays. In North America, IBS is far more common in women than in men.

Etiology

The cause of IBS is unknown, but it is thought to be due to a hypersensitivity of the bowel wall leading to disruption of the normal function of the intestinal muscles. There is a familial predisposition. Stress, caffeine, and sensitivity to certain foods such as dairy and wheat products seem to trigger IBS in some people.

Pathophysiology

An altered bowel pattern and abdominal pain with bloating are caused by altered motility of the small and large intestines. It is thought that with IBS there is an abnormality of nerve function in the intestine. A chemical mediator, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) or serotonin, plays a role in bowel motility and visceral sensitivity; 5-HT may be implicated in the pain that occurs with IBS.

Signs and Symptoms

IBS is a group of symptoms that together represent the most common disorder presented by patients who consult gastroenterologists. The three characteristics typical of this disorder are (1) alteration in bowel elimination (either constipation or diarrhea or both); (2) abdominal pain and bloating; and (3) the absence of detectable organic disease. The pattern of bowel dysfunction varies from case to case and each patient seems to have a unique pattern.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of IBS is based on clinical manifestations and ruling out the presence of organic bowel disease. Diagnostic criteria include:

Diarrhea or Constipation

Treatment and Nursing Management

A good general health assessment is conducted along with a focused assessment. Treatment of IBS is long. Medications are prescribed according to each patient’s need. Drugs that have been used include bulk-forming agents, antidiarrheals, antispasmodics, antidepressants, anticholinergics/sedatives, and mild analgesics to relieve discomfort (Table 30-1). A diet high in fiber also may be prescribed. Metamucil or other bulk stool softeners may be recommended.

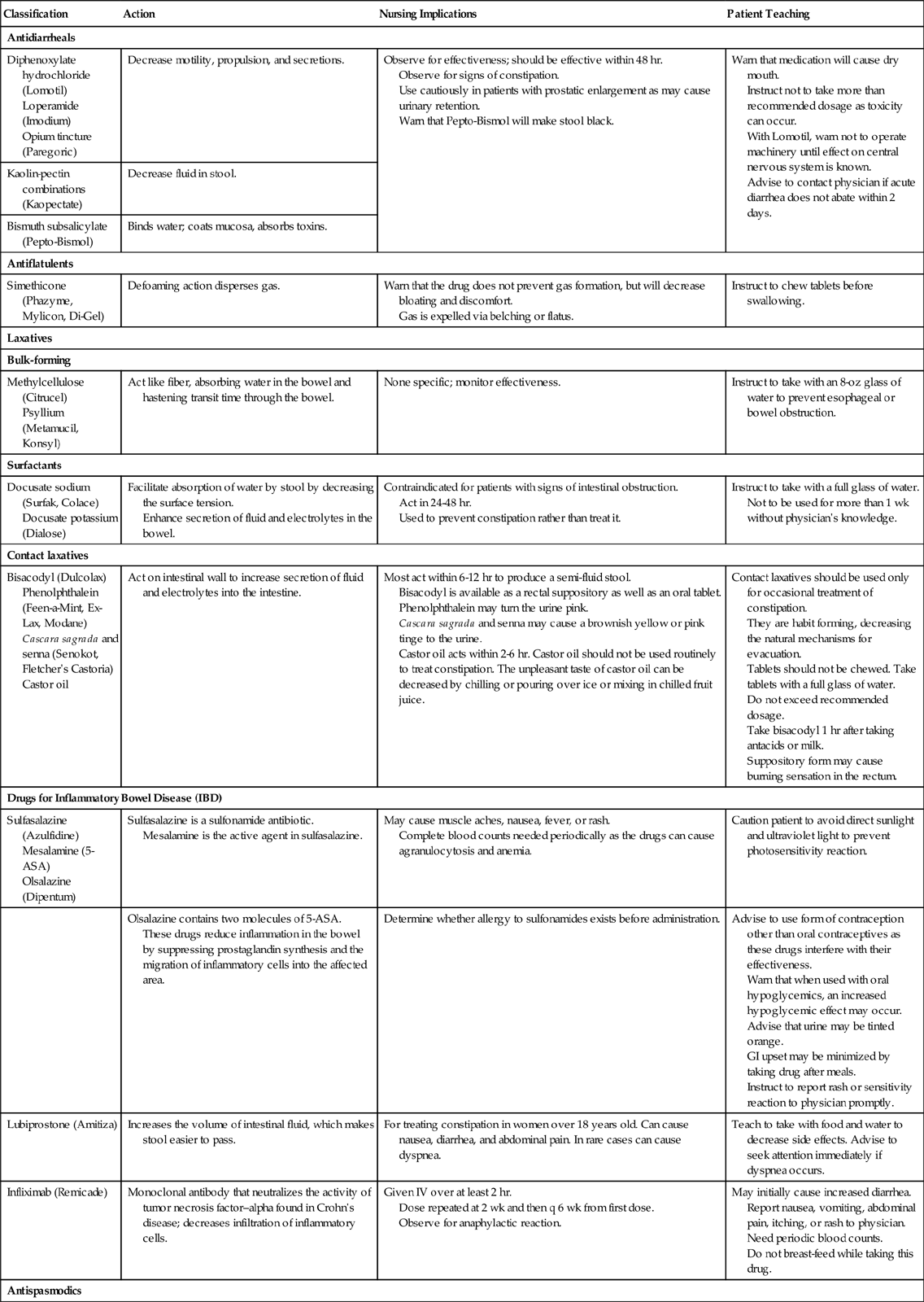

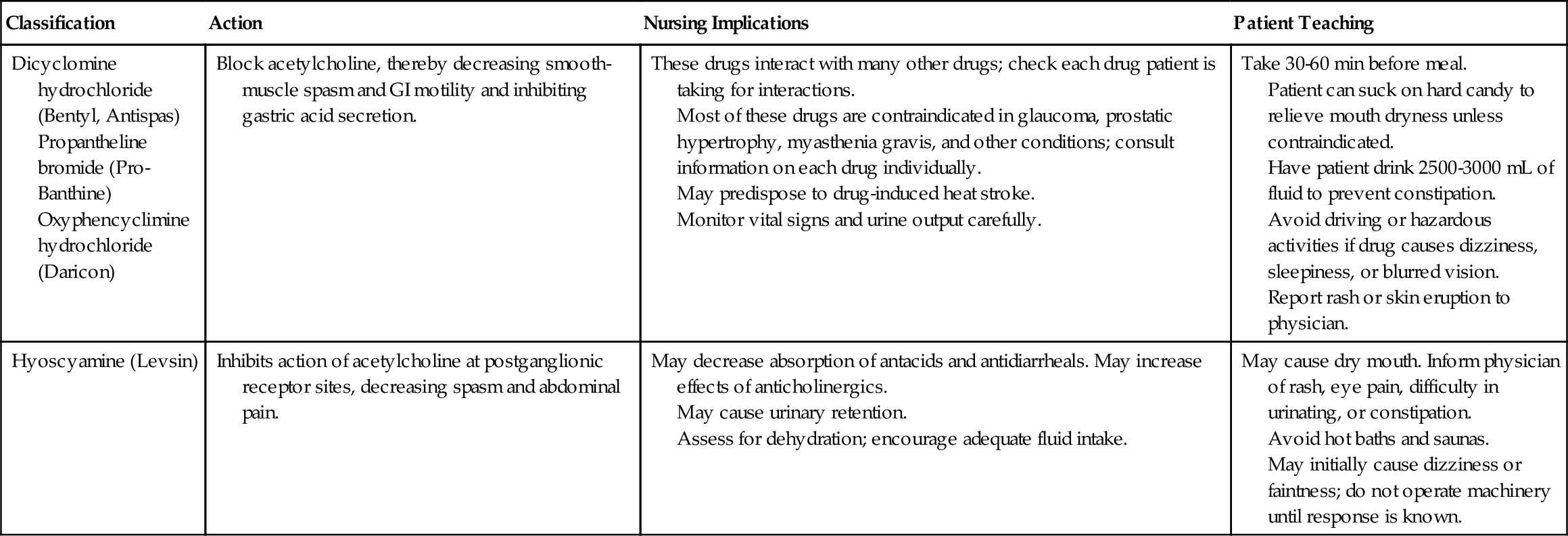

Table 30-1

Table 30-1

Commonly Prescribed Drugs for Gastrointestinal Disorders

| Classification | Action | Nursing Implications | Patient Teaching |

| Antidiarrheals | |||

| Diphenoxylate hydrochloride (Lomotil) Loperamide (Imodium) Opium tincture (Paregoric) | Decrease motility, propulsion, and secretions. | Observe for effectiveness; should be effective within 48 hr. Observe for signs of constipation. Use cautiously in patients with prostatic enlargement as may cause urinary retention. Warn that Pepto-Bismol will make stool black. | Warn that medication will cause dry mouth. Instruct not to take more than recommended dosage as toxicity can occur. With Lomotil, warn not to operate machinery until effect on central nervous system is known. Advise to contact physician if acute diarrhea does not abate within 2 days. |

| Kaolin-pectin combinations (Kaopectate) | Decrease fluid in stool. | ||

| Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) | Binds water; coats mucosa, absorbs toxins. | ||

| Antiflatulents | |||

| Simethicone (Phazyme, Mylicon, Di-Gel) | Defoaming action disperses gas. | Warn that the drug does not prevent gas formation, but will decrease bloating and discomfort. Gas is expelled via belching or flatus. | Instruct to chew tablets before swallowing. |

| Laxatives | |||

| Bulk-forming | |||

| Methylcellulose (Citrucel) Psyllium (Metamucil, Konsyl) | Act like fiber, absorbing water in the bowel and hastening transit time through the bowel. | None specific; monitor effectiveness. | Instruct to take with an 8-oz glass of water to prevent esophageal or bowel obstruction. |

| Surfactants | |||

| Docusate sodium (Surfak, Colace) Docusate potassium (Dialose) | Facilitate absorption of water by stool by decreasing the surface tension. Enhance secretion of fluid and electrolytes in the bowel. | Contraindicated for patients with signs of intestinal obstruction. Act in 24-48 hr. Used to prevent constipation rather than treat it. | Instruct to take with a full glass of water. Not to be used for more than 1 wk without physician’s knowledge. |

| Contact laxatives | |||

| Bisacodyl (Dulcolax) Phenolphthalein (Feen-a-Mint, Ex-Lax, Modane) Cascara sagrada and senna (Senokot, Fletcher’s Castoria) Castor oil | Act on intestinal wall to increase secretion of fluid and electrolytes into the intestine. | Most act within 6-12 hr to produce a semi-fluid stool. Bisacodyl is available as a rectal suppository as well as an oral tablet. Phenolphthalein may turn the urine pink. Cascara sagrada and senna may cause a brownish yellow or pink tinge to the urine. Castor oil acts within 2-6 hr. Castor oil should not be used routinely to treat constipation. The unpleasant taste of castor oil can be decreased by chilling or pouring over ice or mixing in chilled fruit juice. | Contact laxatives should be used only for occasional treatment of constipation. They are habit forming, decreasing the natural mechanisms for evacuation. Tablets should not be chewed. Take tablets with a full glass of water. Do not exceed recommended dosage. Take bisacodyl 1 hr after taking antacids or milk. Suppository form may cause burning sensation in the rectum. |

| Drugs for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | |||

| Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine) Mesalamine (5-ASA) Olsalazine (Dipentum) | Sulfasalazine is a sulfonamide antibiotic. Mesalamine is the active agent in sulfasalazine. | May cause muscle aches, nausea, fever, or rash. Complete blood counts needed periodically as the drugs can cause agranulocytosis and anemia. | Caution patient to avoid direct sunlight and ultraviolet light to prevent photosensitivity reaction. |

| Olsalazine contains two molecules of 5-ASA. These drugs reduce inflammation in the bowel by suppressing prostaglandin synthesis and the migration of inflammatory cells into the affected area. | Determine whether allergy to sulfonamides exists before administration. | Advise to use form of contraception other than oral contraceptives as these drugs interfere with their effectiveness. Warn that when used with oral hypoglycemics, an increased hypoglycemic effect may occur. Advise that urine may be tinted orange. GI upset may be minimized by taking drug after meals. Instruct to report rash or sensitivity reaction to physician promptly. | |

| Lubiprostone (Amitiza) | Increases the volume of intestinal fluid, which makes stool easier to pass. | For treating constipation in women over 18 years old. Can cause nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. In rare cases can cause dyspnea. | Teach to take with food and water to decrease side effects. Advise to seek attention immediately if dyspnea occurs. |

| Infliximab (Remicade) | Monoclonal antibody that neutralizes the activity of tumor necrosis factor–alpha found in Crohn’s disease; decreases infiltration of inflammatory cells. | Given IV over at least 2 hr. Dose repeated at 2 wk and then q 6 wk from first dose. Observe for anaphylactic reaction. | May initially cause increased diarrhea. Report nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, itching, or rash to physician. Need periodic blood counts. Do not breast-feed while taking this drug. |

| Antispasmodics | |||

| Dicyclomine hydrochloride (Bentyl, Antispas) Propantheline bromide (Pro-Banthine) Oxyphencyclimine hydrochloride (Daricon) | Block acetylcholine, thereby decreasing smooth-muscle spasm and GI motility and inhibiting gastric acid secretion. | These drugs interact with many other drugs; check each drug patient is taking for interactions. Most of these drugs are contraindicated in glaucoma, prostatic hypertrophy, myasthenia gravis, and other conditions; consult information on each drug individually. May predispose to drug-induced heat stroke. Monitor vital signs and urine output carefully. | Take 30-60 min before meal. Patient can suck on hard candy to relieve mouth dryness unless contraindicated. Have patient drink 2500-3000 mL of fluid to prevent constipation. Avoid driving or hazardous activities if drug causes dizziness, sleepiness, or blurred vision. Report rash or skin eruption to physician. |

| Hyoscyamine (Levsin) | Inhibits action of acetylcholine at postganglionic receptor sites, decreasing spasm and abdominal pain. | May decrease absorption of antacids and antidiarrheals. May increase effects of anticholinergics. May cause urinary retention. Assess for dehydration; encourage adequate fluid intake. | May cause dry mouth. Inform physician of rash, eye pain, difficulty in urinating, or constipation. Avoid hot baths and saunas. May initially cause dizziness or faintness; do not operate machinery until response is known. |

5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; GI, gastrointestinal; IV, intravenously.

Gas-forming foods such as legumes and those in the cabbage family should be avoided. Avoiding onions, potatoes, cucumbers, coffee, tea, carbonated beverages, and alcohol can be helpful. In some patients, milk is restricted if they have shown evidence of intolerance to it. Lactase tablets may be used, but these may not help if there is sensitivity to dairy products rather than a lactase deficiency. Wearing loose clothing is more comfortable if bloating or increased abdominal pressure occurs. Give instruction about the medications and diet therapy.

Ineffective coping patterns in response to stress may be present in these patients. Randomized, controlled

trials have shown cognitive therapy, psychotherapy, and hypnotherapy help to improve overall symptoms (Harvard Women’s Health Watch, 2009).  Consultation with a psychiatric nursing specialist can help the staff nurse develop more realistic goals and effective nursing interventions to improve the patient’s coping skills.

Consultation with a psychiatric nursing specialist can help the staff nurse develop more realistic goals and effective nursing interventions to improve the patient’s coping skills.

Diverticula

The term diverticulum refers to a small, blind pouch resulting from a protrusion of the mucous membranes of a hollow organ through weakened areas of the organ’s muscular wall. Diverticula are most prevalent in older individuals and occur most often in the intestinal tract, especially in the esophagus and colon. When diverticula are present, the patient is said to have diverticulosis.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Diverticula tend to develop in people over age 50 who have chronic constipation and/or eat a low-fiber diet.  Diverticulitis occurs when the diverticula become inflamed or infected. Waste accumulates in the diverticula and can irritate the mucosal wall. Diverticulitis affects one third of adults over age 60.

Diverticulitis occurs when the diverticula become inflamed or infected. Waste accumulates in the diverticula and can irritate the mucosal wall. Diverticulitis affects one third of adults over age 60.

Increases in intra-abdominal pressure from constipation and straining to defecate are thought to be factors in the development of colon diverticula. Muscle of the colon hypertrophies, thickens, and becomes rigid. The increased intra-abdominal pressure causes herniation of the mucosa and submucosa through the colon wall. Diverticulitis occurs when food caught in the diverticulum mixes with bacteria. The intestinal wall becomes irritated and infected, and if it is not treated, perforation and peritonitis may occur.

Esophageal diverticula occur when there is herniation of esophageal mucosa and submucosa into surrounding tissue. The disorder is more common in older patients.

Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

A person with diverticulosis may initially be asymptomatic; however symptoms will develop when inflammation or infection occurs because material has lodged in diverticula. For bowel diverticula, there is usually a history of constipation. There may be rectal bleeding. Diverticulitis of the intestine produces symptoms of diarrhea or constipation, acute severe left lower abdominal pain, fever, and rectal bleeding. The condition may be complicated by intestinal obstruction or by peritonitis if the intestinal wall ruptures. If bleeding is massive, there will be hypotension and dehydration and eventual shock. Computed tomography with contrast is the preferred diagnostic test. Barium enema and colonoscopy should be avoided in acute cases, due to risk of bowel perforation (Carroll, 2009).

Esophageal diverticula produce complaints of dysphagia, regurgitation, nocturnal cough, and halitosis (bad breath). There is a risk of esophageal perforation.

Treatment and Nursing Management

Diverticulosis often can be managed conservatively. A high-fiber diet, increased fluids and bulk laxatives, or stool softeners to control constipation may be all that are needed.

For diverticulitis, antidiarrheal medication may be prescribed. The role of the LPN/LVN is to reinforce education about the diet, fluid intake, and exercise. Mild pain medication may be used for abdominal discomfort in the ambulatory patient. In acute cases of diverticulitis, parenteral antibiotics, nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status for 2 to 3 days and intravenous (IV) fluids may be necessary. Meperidine (Demerol) may be prescribed for pain, rather than morphine, because morphine increases intraluminal pressure (Carroll, 2009). Recurrent episodes of diverticulitis, or perforation and peritonitis, require surgical removal of the affected part of the colon.

Recurrent episodes of diverticulitis, or perforation and peritonitis, require surgical removal of the affected part of the colon.

Intestinal Obstruction

Intestinal obstruction is a sudden or gradual blockage of the intestinal tract that prevents the normal passage of gastrointestinal (GI) contents through the intestines.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

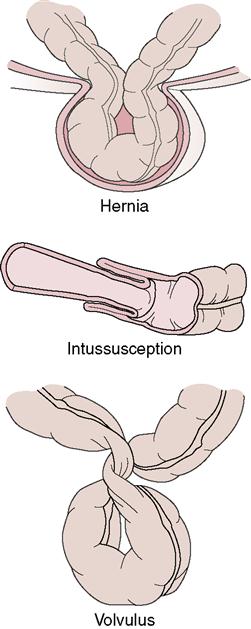

Mechanical obstruction results in blockage of the lumen of the bowel. Examples include tumors, adhesions, strangulated hernia, twisting of the bowel (volvulus), telescoping of one part of the bowel into another (intussusception), gallstones, barium impaction, and intestinal parasites (Figure 30-2). Abdominal adhesions are a common cause of intestinal obstruction. Adhesions form when inflammation from abdominal trauma or surgery has occurred, and fibrous bands of scar tissue hold together two segments of bowel that are normally separated.

Nonmechanical obstruction results from the absence of peristalsis (movement of contents through the bowel stops). Nonmechanical obstructions may

occur as a result of paralytic ileus (failure of forward movement of bowel contents) following abdominal surgery, from infection, or as a consequence of hypokalemia. Nonmechanical obstructions may be secondary to intestinal thrombus. Infections can occur in some pelvic inflammatory diseases or peritonitis, in uremia, and in heavy-metal poisoning. All of these conditions can interfere with normal peristaltic action and produce a nonmechanical obstruction.

When obstruction occurs, fluid and gas accumulate in the intestine, increasing intraluminal pressure. Peristaltic waves above the obstruction may occur as the intestine attempts to move material down the tract. These waves may cause severe pain.

Signs and Symptoms

The symptoms of intestinal obstruction vary according to the location of the obstruction. Obstructions occurring high in the intestinal tract are characterized by sharp, brief pains in the upper abdomen. Frequent bowel sounds are high pitched above the point of obstruction, and bowel sounds are absent below the obstruction. Other symptoms include vomiting, with rapid dehydration and only slight abdominal distention. An acute intestinal obstruction in the upper abdomen can cause respiratory difficulty because of the pressure of the distended abdomen against the diaphragm.

Obstructions of the colon are characterized by a more gradual onset, with marked abdominal distention as the bowel fills, infrequent vomiting (which occurs late in the process if at all), and pains that last several minutes or longer and correspond to peristaltic waves. Fecal odor or material in the emesis suggests a complete intestinal obstruction.

Diagnosis and Treatment

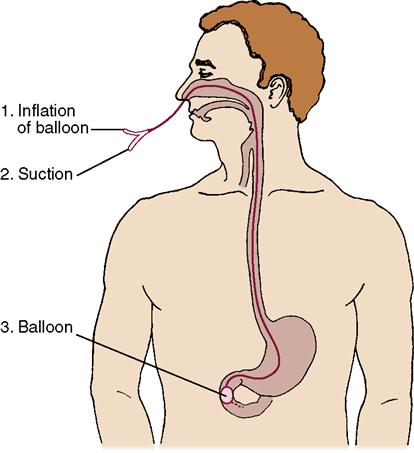

Diagnostic x-rays are ordered to locate the obstruction. For some patients, the insertion of an intestinal tube, which is a long tube inserted via the nose (Figure 30-3) relieves the obstruction by decompressing the intestine above the obstruction. Surgery is indicated for obstruction caused by adhesions, volvulus, hernia, or tumor. Adhesions are lysed (broken apart), a volvulus is untwisted, or a colectomy may be necessary if tumor is involved.

Nursing Management

Placing the patient in Fowler’s position helps relieve pressure and also aids in removing gas and intestinal contents through the intestinal tube. Fluid and electrolyte status must be monitored closely. Measure abdominal girth every 2 to 4 hours, by placing the tape at the same location on the abdomen each time. Pain control is essential, but worsening pain may signal an unresolved, intestinal obstruction which can lead to rupture of the intestine, peritonitis, shock, and death. If the obstruction cannot be resolved, surgical correction must be done. Postoperative care is the same as for other abdominal surgery patients (see Chapter 5 and Nursing Care Plan 30-1 on pp. 676–678 and 30-2 on Evolve).

Bowel Ischemia

Bowel ischemia occurs when the blood supply to the bowel is insufficient to support metabolic needs. It can be an acute process with a sudden onset of symptoms, or a chronic condition.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The problem may involve the arterial or the venous blood supply in the form of emboli, thrombosis, or the gradual narrowing and occlusion of vessels. Ischemia can occur as the result of a bowel obstruction or as the result of hypovolemic shock. Underlying cardiac conditions—such as atrial fibrillation or use of vasoconstrictive drugs—can be contributing factors.

Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

A careful history is necessary, because the symptoms are similar to many other abdominal disorders. The sudden onset of severe abdominal pain signals an acute condition. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps may also be present. The abdomen is tender to palpation and the patient will exhibit guarding. Bowel sounds will be minimal or absent. The white blood cell count is likely to be elevated. Computed tomography angiography is used to confirm the medical diagnosis.

Treatment and Nursing Management

The patient will be NPO and a nasogastric (NG) tube will be inserted to relieve distention. IV hydration is usually ordered, and a Foley catheter may be used to monitor output in the acute phase. If the damage is not severe, conservative measures such as bowel rest and IV hydration will continue. If damage is severe or if the cause is related to an unresolved anatomical obstruction, the patient may require surgery.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) commonly starts between ages 15 and 35. There is a growing tendency to include both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease under the title of IBD. Ulcerative colitis is an inflammation, with formation of ulcers of the mucosa of the colon. It often is a chronic disease and the patient is usually asymptomatic between acute flare-ups. People with ulcerative colitis have a 40% higher incidence of some types of arthritis. Crohn’s disease can involve any part of the GI tract, but most commonly affects the distal ileum and proximal colon.

Etiology

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis have a genetic predisposition. Both disorders also have an ethnic correlation as they are more common among the Jewish population. Immunologic activity is thought to be involved as well because anticolon antibodies are often present in the blood. With ulcerative colitis, infections and emotional tension frequently bring about acute attacks.

Pathophysiology

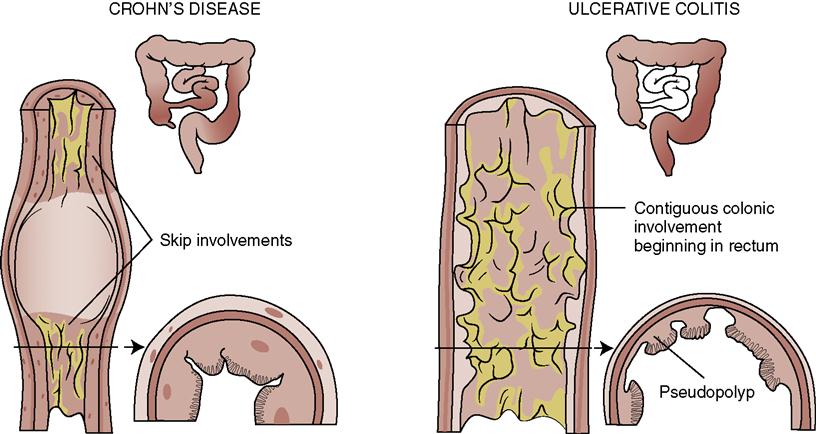

The pathophysiology of IBD is being investigated. It is suspected that ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are immunologic responses to the same (as-yet-unknown) etiologic agent. The end result is inflammation of the mucosal lining of the intestinal tract, causing ulceration, edema, bleeding, and fluid and electrolyte loss. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (regional ileitis) share many of the same characteristics (Table 30-2). One difference is that the inflammatory changes in ulcerative colitis are nonspecific, whereas those in Crohn’s disease are granulomatous (a mass of inflamed tissue characterized by the presence of small granules). Patients with long-standing chronic ulcerative colitis are at 10 to 20 times greater risk for developing cancer of the colon than patients with Crohn’s disease. The constant inflammation disrupts normal cell function, and cellular mutations may occur. Crohn’s disease can affect any area of the intestine, although it more frequently affects the ascending colon and can affect the small intestine (Figure 30-4). Ulcerative colitis most often affects the rectosigmoid and left colon. Changes due to ulcerative colitis tend to be continuous along the affected portion of the bowel, whereas changes due to Crohn’s disease are segmental, leaving healthy sections of bowel in between diseased portions (“skip lesions”). With Crohn’s disease, radiograph reveals a cobblestone appearance to the mucosa.

Table 30-2

Comparison of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease

| Ulcerative Colitis | Crohn’s Disease | |

| Area affected | Mucosa only; usually involves rectum and proceeds up the colon | Full thickness of the intestine; most common in small intestine |

| Characteristics | Mucosa is red, intestinal wall is edematous and friable, bleeding easily; pseudopolyps are present | Edematous bowel wall, inflammatory cells, mucosal ulcerations, granulomas, and “skip” lesions (normal areas) |

| Signs and symptoms | Diarrhea, frequently bloody; abdominal cramping relieved by defecation; rectal bleeding | Fever, malaise, fatigue, weight loss, intermittent diarrhea, cramping or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain, postprandial bloating |

| Complications | Massive hemorrhage; hypovolemia, toxic megacolon (rapid dilation of the intestines), cancer of the colon | Fistulas, anal fissures, perianal disease, bowel obstruction or perforation |

Signs and Symptoms

The patient with IBD suffers from attacks of diarrhea that may be bloody and contain mucus; abdominal pain with cramping; malaise; fever; and weight loss. The color of blood in the stool depends on the degree and rapidity of the bleed. Slow bleeding and oozing will show a black, tarry stool. If diarrhea is frequent, the blood may be more reddish. The stool color is also dependent on where in the intestine the bleeding is occurring. Blood tends to be redder when the bleeding location is lower in the intestine. The bouts of IBD symptoms often are precipitated by events that cause undue physical or emotional stress. An acute attack can last for days, weeks, or even months, followed by periods of remission extending from a few weeks to several decades. A few patients experience only one attack, and then remain free of symptoms for the rest of their lives. Others have serious intestinal hemorrhage with fluid and electrolyte imbalances.

Diagnosis

Medical diagnosis of IBD usually is based on the patient’s medical history and symptoms. Colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, mucosal biopsy, barium enema, and stool analysis may be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Treatment for either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease varies according to severity of symptoms and whether the condition becomes chronic. Conservative approaches to medical treatment include administration of antidiarrheal drugs, long-term sulfasalazine therapy, and medications to relieve abdominal cramps. The recommended diet consists of low-fat, low-fiber foods that are high in protein and calories. Small frequent feedings are best. Lactose avoidance helps some patients. Corticosteroids are used for moderate to severe cases to decrease the inflammation. During acute attacks, fluid replacement may be necessary. Blood transfusions are given when anemia is present. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) derivatives, such as olsalazine sodium (Dipentum), are useful for those patients who cannot tolerate sulfasalazine (see Table 30-1). Budesonide (Entocort) is used to help control disease in the ileum. Patients with advanced disease who are not surgical candidates may be given azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, levamisole, or cyclosporine to help control the disease (Tocco, 2009).

Infliximab (Remicade), a monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor, has greater than 80% response rate for Crohn’s disease, but only about a 50% success rate with ulcerative colitis. The drug is extremely expensive and is given IV by a set protocol. Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) is a new drug for patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease who have not responded to conventional treatments.

Surgical intervention is an alternative treatment for some patients. The surgical procedure usually involves removing the affected portion of the bowel, often by proctocolectomy, and creating an ileostomy. Today a patient with ulcerative colitis may be a candidate for an ileal reservoir (Kock pouch) or an ileoanal anastomosis rather than a standard ileostomy. Both of these procedures allow the patient control over the discharge of wastes from the reservoir, and consequently a collection pouch is not necessary. The patient uses a catheter to empty the reservoir after the Kock procedure. With an ileoanal anastomosis, the patient retains control over the anal sphincter with voluntary defecation. These procedures are not performed often for Crohn’s disease because as the disease progresses, the area of the reservoir is involved.

Nursing Management

Assessment (Data Collection)

A complete health assessment is performed with particular attention to pain, nutritional, and fluid and electrolyte status. A thorough abdominal assessment is performed.

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

Nursing diagnoses might include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

will further reduce the tone of the colon (Beach, 2008).

will further reduce the tone of the colon (Beach, 2008).