Theris A. Touhy

Care across the continuum

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

“This is my home. We are all like a family, and I will die here. The girls that help me during the day, we treat one another like family members. We have some days when we are grumpy, some days we are happy, and we don’t hold our feelings back, like you would do with your own family at home.”

An 85-year-old resident of a skilled nursing facility

“We are their family now, and that is how we have to treat them. I think we do a pretty good job here because a lot of patients say when they leave and come back, ‘Oh, I am so glad to be home.’ Our philosophy here is that we don’t work at this facility, we are guests in these people’s home.”

A 50-year-old director of nursing in a skilled nursing facility

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Identify interventions to improve care for older adults in acute and long-term care settings.

• Describe factors influencing the provision of long-term care including the culture change movement.

Glossary

Physiatrist Medical doctors who have completed training in the medical specialty of physical medicine and rehabilitation

Transitional care The broad range of services and environments designed to promote the safe and timely passage of patients between levels of care and across care settings (Naylor & Keating, 2008, p. 65).

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

A mobile, youth-oriented society may find it difficult to fully comprehend the insecurity that elders feel when moving from one site to another in their later years. In addition to the stress of relocation and the initial anxiety of adapting to a new setting, elders typically move to ever more restrictive environments, often in times of crisis. This chapter discusses residential care options across the continuum and transitions between health care settings with related implications for nursing practice. Professional nursing roles in settings across the continuum where care is provided to older adults are discussed in Chapter 2.

Elder-friendly communities

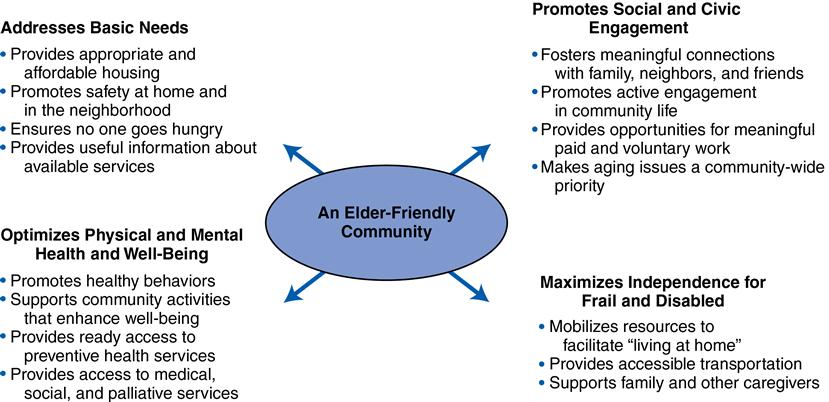

“Home” provides basic shelter, is a place to establish security, and is the place where one “belongs.” It should provide the highest possible level of independence, function, safety, and comfort. Most older people prefer to remain in their own homes and “age-in-place,” rather than relocate to more protected settings, especially institutional living. Future generations of older people will be much more likely to want to remain living independently and seek opportunities to adapt homes and communities to meet their needs. The ability to age-in-place depends on appropriate support for changing needs so the older person can stay where he or she wants. Developing elder-friendly communities and increasing opportunities to age-in-place can enhance the health and well-being of older people. Enabling the community to become the good neighbor to older citizens provides mutual benefits to all who are involved.

Components of an elder-friendly community include the following: (1) addresses basic needs; (2) optimizes physical health and well-being; (3) maximizes independence for the frail and disabled; and (4) provides social and civic engagement. Figure 3-1 presents elements of an elder-friendly community. Many state and local governments are assessing the community and designing interventions to enhance the ability of older people to remain in their homes and familiar environments. These interventions range from adequate transportation systems to home modifications and universal design standards for barrier-free housing. Home design features such as 36-inch-wide doorways and hallways, a bathroom on the first floor, an entry with no steps, outlets at wheelchair level, and reinforced walls in bathrooms to support grab bars will become standard nationwide in the next 50 years (Robinson & Reinhard, 2009).

Advancements in all types of technology hold promise for improving quality of life, decreasing the need for personal care, and enhancing the ability to live safely at home and age-in-place (Daniel et al., 2009). Some emerging technologies to enhance safety and independent living for older adults are discussed in Chapter 13.

Residential options in later life

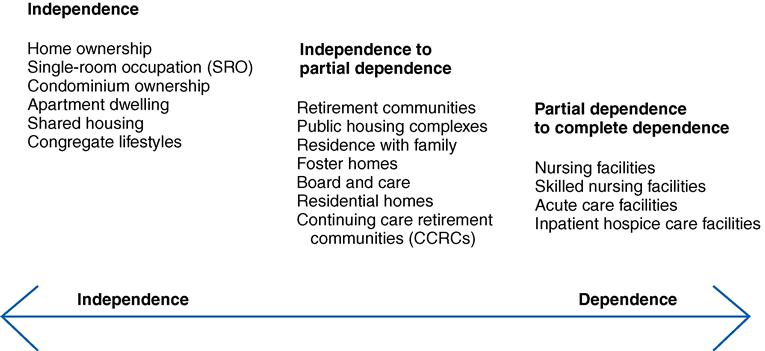

Some older people, by choice or by need, move from one type of residence to another. A number of options exist, especially for those with the financial resources that allow them to have a choice. Residential options range along a continuum from remaining in one’s own home; to senior retirement communities; to shared housing with family members, friends, or others; to residential care communities such as assisted living settings; to nursing facilities for those with the most needs (Figure 3-2). There are many different models of senior housing, and older people may seek assistance from nurses in choosing what kind of living situation will be best for them. It is important to be aware of the various options available in your local community as well as the advantages, disadvantages, cost, and services provided in each option. When discharging older people from the hospital or long-term care facility, knowledge of where they live or the type of setting to which they are being discharged will assist in providing appropriate resources and teaching so that outcomes can be enhanced for both the individual and his or her family.

Shared housing

Shared housing among adult children and their older relatives has become a choice for many because of cultural preferences or need. The sharing may relieve the economic burdens of maintaining a home after widowhood or retirement on a fixed income. Historically, strong cultural influences predict the frequency of multigenerational residences. Among Asians, South Americans, and African Americans, it is often an expectation. Growth of multigenerational households has accelerated during the economic downturn among all cultures and races and this trend is expected to continue (Hooyman & Kiyak, 2011). Relocating from one’s own home to the home of an adult child can have many benefits for both, but without adequate preparation it can also be stressful. Box 3-1 presents some factors to consider when planning to add an older person to the household.

A variation of multigenerational housing has long existed in what has become known as “granny flats.” These may be apartments added to existing homes or the construction of small housing units on family property with privacy as well as sharing of time and resources. Such arrangements allow families to be close enough to be of assistance if needed but to remain separate. They are practical and economical, and their production has continually expanded, particularly in Australia. In the United States, use of this model is minimal, but existing “mother-in-law” cottages and apartments have served a similar purpose for many families for years.

Another model of shared housing is that of opening one’s personal home to others. Older people often live in houses that were purchased in their young adult years and find that, as they age, much of the space may be underused. Sharing a house can be easily implemented by locating, screening, and matching older people looking for houses to share with those who have them. The National Shared Housing Resource Center (NSHRC) (http://www.nationalsharedhousing.org/) has established subgroups to assist individuals interested in home sharing. Those who have done so report feeling safer and less lonely.

Population-specific communities

As the number of senior communities expands, older adults will have more options of moving somewhere that they find especially welcoming. These options include communities that emphasize a particular sport, like tennis or golf. Groups of people can also come together to form intentional communities, buying a cluster of home tracts and building in such a way to support their particular lifestyles or needs or personalities. Still others provide unique additional services, such as those in communities that specialize in providing residences for persons with, for example, a mental illness, alcoholism, or developmental disabilities.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) seniors face several problems in housing in their older years. They may have little family support and may face discrimination in housing options. Many LGBT seniors say they do not feel welcome at traditional residential options. Those who want to live together are discouraged from doing so by some organizations. Residential facilities and communities designed specifically for LGBT seniors are increasing in number across the country. Nurses should be aware of this heretofore invisible group of older adults who need access to welcoming resources. Chapter 24 discusses issues specific to LGBT seniors in more depth.

Senior retirement communities

Communities designed for elders are proliferating. Numerous combinations of single-family homes, apartments, activities, optional services, meals in the home, cafeterias, restaurants, housekeeping, and security are available. In some cases, emergency services and health clinics are adjacent. These are all designed to make independent living feasible with the least effort on the part of the elder. Some senior communities are luxurious and have a wide range of physical and cultural amenities; others are simpler, providing only the basic necessities. Prices are consistent with the level of luxury provided and the range of services available.

Although the costs of the majority of senior communities are borne by the consumers, for elders with limited incomes, federally subsidized rental options are available in some areas of the country. Older adults benefiting from this option are assisted through rental housing subsidized by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Although not all HUD housing is designated for senior living, Section 202 of the Housing Act, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, approved the construction of low-rent units especially for older people. These units may also have provisions for health care, recreation, and transportation.

Community and home care

Nurses will care for older adults in hospitals and long-term care, but the majority of older adults live in the community. Community-based care settings include home care services, independent senior housing, retirement communities, residential care facilities, adult day health programs, primary care clinics, and public health departments. The growth in home and community health care is expected to continue because older people prefer to age in place. Other factors influencing the growth of home-based care include rapidly escalating health care costs. Chapter 2 discusses roles for nurses in home and community care.

An innovative long standing community-based program is Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE). PACE is an alternative to nursing home care for frail older people who want to live independently in the community with a high quality of life. It provides a comprehensive continuum of primary care, acute care, home care, nursing home care, and specialty care by an interdisciplinary team. PACE is a capitated system in which the team is provided with a monthly sum to provide all care to the enrollees, including medications, eyeglasses, and transportation to care as well as urgent and preventive care. Participants must meet the criteria for nursing home admission, prefer to remain in the community, and be eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Adult day services are also provided.

PACE is now recognized as a permanent provider under Medicare and a state option under Medicaid. PACE has been approved by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) as an evidence-based model of care. Models such as PACE are innovative care delivery models, and continued development of such models are important as the population ages. More information about PACE models and outcomes of care can be found at http://www.npaonline.org/website/article.asp?id=12.

Adult day services

Adult day services (ADS) are community-based group programs designed to provide social and some health services to adults who need supervised care in a safe setting during the day. They also offer caregivers respite from the responsibilities of caregiving, and most provide educational programs for caregivers and support groups. The most recent nationwide survey of adult day centers confirmed that there are over 4600 adult day services centers in the United States providing care for 150,000 care recipients each day—a 35% increase since 2002. Adult day centers are serving populations with higher levels of physical disability and chronic disease, and the number of older people receiving adult day services has increased 63% over the last 8 years (National Adult Day Services Association, Ohio State University College of Social Work, MetLife Mature Market Institute, 2010).

Adult day services are an important part of the long-term care continuum and a cost-effective alternative or supplement to home care or institutional care. ADS are increasingly being utilized to provide community-based care for conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and for transitional care and short-term rehabilitation following hospitalization. Local Area Agencies on Aging are good sources of information about adult day services and other community-based options.

Residential care facilities

Residential care facility (RCF) is the broad term for a range of nonmedical, community-based residential settings that house two or more unrelated adults and provide services such as meals, medication supervision or reminders, activities, transportation, or assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs). RCFs are known by more than 30 different names across the country, including adult congregate facilities, foster care homes, personal care homes, homes for the elderly, domiciliary care homes, board and care homes, rest homes, family care homes, retirement homes, and assisted living facilities.

RCFs are the fastest growing housing option available for older adults in the United States. This kind of facility is viewed as more cost effective than nursing homes while providing more privacy and a homelike environment. Medicare does not cover the cost of care in these types of facilities. In some states, costs may be covered by private and long-term care insurance and some other types of assistance programs. Residential care payment is primarily private pay, although 41 states currently have a Medicaid Waiver/Medicaid State Plan for a limited amount of eligible individuals. The use of Medicaid financing for services in RCFs has gradually increased in recent years. The rates charged and what services those rates include vary considerably, as do regulations and licensing.

Assisted living

A popular type of residential care can be found in assisted living facilities (ALFs), also called board and care homes or adult congregate living facilities (ACLFs). Assisted living is a residential long-term care choice for older adults who need more than an independent living environment but do not need the 24 hours/day skilled nursing care and the constant monitoring of a skilled nursing facility. The typical ALF resident is an 86-year-old woman who is mobile but needs assistance with two ADLs (Box 3-2). Assisted living settings may be a shared room or a single-occupancy unit with a private bath, kitchenette, and communal meals. They all provide some support services.

Assisted living is more expensive than independent living and less costly than skilled nursing home care, but it is not inexpensive. There are 31,110 ALFs in the United States and most are private, for-profit facilities. Costs vary by geographical region, size of the unit, and relative luxury. The national average base rate for an ALF (single room and board and limited other services) is $3300 monthly (AssistedLivingFacilities.org, 2012). Most ALFs offer two or three meals per day, light weekly housekeeping, and laundry services, as well as optional social activities. Each added service increases the cost of the setting but allows for individuals with resources to remain in the setting longer, as functional abilities decline.

Many seniors and their families prefer ALFs to nursing homes because they cost less, are more homelike, and offer more opportunities for control, independence, and privacy. However, many residents of ALFs have chronic care needs and over time may require more care than the facility is able to provide. Services (e.g., home health, hospice, homemakers) can be brought into the facility, but some question whether this adequately substitutes for 24-hour supervision by registered nurses (RNs). Not every ALF has an RN or licensed practical–vocational nurse (LPN/LVN), and, in most states, any skilled nursing provided by the staff other than nurse-delegated assistance with self-administered medication is prohibited. In the ALF, there is no organized team of providers such as that found in nursing homes (i.e., nurses, social workers, rehabilitation therapists, pharmacists).

With the growing number of older adults with dementia residing in ALFs, many are establishing dementia-specific units. It is important to investigate services available as well as staff training when making decisions as to the most appropriate placement for older adults with dementia. Continued research is needed on best care practices as well as outcomes of care for people with dementia in both ALFs and nursing homes. The Alzheimer’s Association has issued a set of dementia care practices for ALFs and nursing homes (Alzheimer’s Association, 2009) and an evidence-based guideline, Dementia Care Practice Recommendations for Assisted Living Residences and Nursing Homes is also available (Tilly & Reed, 2006) (see also www.guideline.gov).

The Joint Commission and the Commission for Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities have published standards for accreditation of ALFs, but many are advocating for more comprehensive federal and state standards and regulations. Appropriate standards of care must be developed and care outcomes monitored to ensure that residents are receiving quality care in this setting, which is almost devoid of professional nursing. Further research is needed on care outcomes of residents in ALFs and the role of unlicensed assistive personnel, as well as RNs, in these facilities.

The American Assisted Living Nurses Association has established a certification mechanism for nurses working in these facilities and has also developed a Scope and Standards of Assisted Living Nursing Practice for Registered Nurses (www.alnursing.org). Advanced practice gerontological nurses are well suited to the role of primary care provider in ALFs, and many have assumed this role. Consumers are advised to inquire as to exactly what services will be provided and by whom if an ALF resident becomes more frail and needs more intensive care. The Assisted Living Federation of America provides a consumer guide for choosing an assisted living residence (http://www.alfa.org/images/alfa/PDFs/getfile.cfm_product_id=94&file=ALFAchecklist.pdf).

Continuing care retirement communities

Continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs), also known as life care communities, provide the full range of residential options, from single-family homes to skilled nursing facilities all in one location. Most of these communities provide access to these levels of care for a community member’s entire remaining lifetime, and for the right price, the range of services may be guaranteed. Having all levels of care in one location allows community members to make the transition between levels without life-disrupting moves. For married couples in which one spouse needs more care than the other, life care communities allow them to live nearby in a different part of the same community. This industry is maturing, and there are 1900 CCRCs in the United States, housing more than 745,000 older adults (Leading Age, 2011).

Most CCRCs are managed by not-for-profit organizations. They usually charge an entry fee ranging from $60,000 to $120,000 that covers and reflects the cost of the residence in which the member will live, the possible future care needed, and the quality and quantity of the community services. The average monthly cost of living in a not-for-profit CCRC is $2,672. Important to remember about these types of communities is that the residence purchased usually belongs to the community after the death of the owner.

Acute care

Older adults often enter the health care system with admissions to acute care settings. Older adults comprise 60% of medical-surgical patients and 46% of critical care patients (Mezey et al., 2007). Acutely ill older adults frequently have multiple chronic conditions and comorbidities and present many care challenges. Hospitals are dangerous places for elders: 34% experience functional decline, and iatrogenic complications occur in as many as 29% to 38%, a rate three to five times higher than in younger patients (Inouye et al., 2000; Kleinpell, 2007). Common iatrogenic complications include functional decline, pneumonia, delirium, new-onset incontinence, urinary tract infections (UTIs), malnutrition, pressure ulcers, medication reactions, and falls—many of the geriatric syndromes. Geriatric syndromes are groups of specific signs and symptoms that occur more often in older adults and can impact morbidity and mortality. Normal aging changes, multiple comorbidities, and adverse effects of therapeutic interventions contribute to the development of geriatric syndromes. These syndromes are discussed in Chapters 7, 9 to 13, and 21. Nursing roles in acute care and model programs to improve care are discussed in Chapter 2.

Recognizing the impact of iatrogenesis, both on patient outcomes and cost of care, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has instituted changes to the inpatient prospective payment system that will reduce payment to hospitals relative to poor care. The changes target conditions (hospital-acquired events (HACs) that are high cost or high volume, result in a higher payment when present as a secondary diagnosis, are not present on admission, and could have reasonably been prevented through the use of evidence-based guidelines. Targeted conditions include catheter-associated UTIs, pressure ulcers, and falls. Use of evidence-based nursing protocols, particularly for these geriatric syndromes, thorough assessment, prevention, and monitoring of treatment responses, and accurate documentation is essential.

Nursing homes (long-term care facilities)

There are approximately 16,100 certified nursing homes in the United States, and more than 1.4 million older adults reside in nursing homes. The majority of nursing homes are for-profit organizations (67%), and nursing home chains own 54% of all nursing homes (Leading Age, 2011). The number of nursing home beds is decreasing in the United States and the number of Medicaid-only beds has decreased by half since 1995 (Gleckman, 2009). This is most likely a result of the increased use of RCFs and more reimbursement by Medicaid programs for community-based care alternatives.

However, skilled nursing facilities are the most frequent site of postacute care in the United States, treating 50% of all Medicare beneficiaries requiring postacute care following hospitalization (Alliance for Quality Nursing Home Care and the American Health Care Association, 2011). With the increasing number of older people, projections are that there will be a threefold increase in the number who will need care in this setting by 2030. Although the percentage of older people living long-term in nursing homes at any given time is low (4% to 5%), people who reach age 65 will likely have a 40% chance of entering a nursing home and those who live to age 85 will have a 1 in 2 chance of spending some time in this setting (Medicare.gov, 2012). This could be for subacute care, ongoing long-term care, or end-of-life care. Chapter 2 discusses the changing nature of skilled nursing facilities and roles for professional nurses in more depth.

People who are cared for in subacute units, as well as long-term units of nursing facilities, require access to rehabilitation and restorative care services that maintain or improve their function and prevent excess disability. These services are required under federal and state regulations and are integral to quality indicators in nursing facilities. Restorative nursing programs for ADLs (e.g., toileting, range of motion, ambulation, and feeding) contribute to restoration and maintenance of function for nursing facility residents who may have been discharged from skilled therapy services or who are not eligible for Medicare reimbursement for rehabilitation services by physical, occupational, or speech therapists. Both rehabilitation and restorative programs require comprehensive multidisciplinary assessment and involvement of the patient and family in development of a plan of care with short and long-term goals (Box 3-3). Rehabilitation and restorative care is increasingly important in light of shortened hospital stays that may occur before conditions are stabilized and the older adult is not ready to function independently.