Theris A. Touhy

Living with chronic illness

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

“Because you understand my disease, you don’t understand me. To understand that I am ill does not mean that you understand how I experience my illness. I am unique. I think and feel and behave in a combination that is unique to me. You do not understand me because you have a label for my disease or a plan for my treatment. It is not my disease or treatment that you need to understand. It is me. This could happen to you…You are just a diagnosis away from being a patient.”

Jevne, 1993, p. 121

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Define chronic illness and explain the differences between chronic illness and acute illness.

• Discuss the factors that influence the experience of chronic illness.

• Identify competencies to improve care for chronic conditions.

• Discuss models to enhance self-care management of chronic illness.

• Discuss nursing interventions to maximize wellness in the presence of chronic illness.

Glossary

Exorbitant Exceeding that which is usual or proper.

Trajectory The path followed by a body or an event moved along by the action of certain forces.

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

Chronic illness

Scope of the problem

The rising prevalence and associated costs of chronic illness is a global health concern. Chronic illness accounts for over half the global health burden. By 2020, estimates are that chronic illness will account for nearly 80% of worldwide disease. Seven out of 10 deaths among Americans each year are from chronic diseases, with heart disease, cancer, and stroke accounting for more than 50% of all deaths each year. Vulnerable and socially disadvantaged people get sicker and die sooner as a result of chronic illness than people of higher social positions. A host of social determinants, especially education, income, gender, and ethnicity influence levels of chronic illness (World Health Organization [WHO], 2012).

Three out of four U.S. health care dollars are spent to care for individuals with chronic illnesses and they account for 80% of the Medicare program’s annual expenditures (Boult & Wieland, 2010). By the year 2020, 25% of the American population will be living with multiple chronic conditions, and costs for managing these conditions will reach $1.07 trillion. Chronic illnesses also exact significant personal costs and burden due to diminished quality of life for both the individual and his or her family and significant others. Access to care, quality outcomes, and patient satisfaction remain issues of concern despite spending. The current health care system excels at responding to immediate medical needs such as accidents, severe injury, and sudden bouts of illness. American health care is less expert at providing ongoing care to people with chronic conditions and improving their day-to-day lives.

Older adults are at high risk for developing chronic illnesses and related disabilities. These chronic conditions include diabetes, arthritis, congestive heart failure, and dementia. Preventing the onset of chronic illness and, after it is diagnosed, reducing the infirmity and disability that can result, remains central to the goal of improving function, well-being, and quality of life for older adults. This chapter discusses chronic illness and the implications for gerontological nursing and healthy aging. Information on specific chronic illnesses and associated symptoms can be found in Chapters 15 to 22.

Chronic and acute illnesses

Chronic illnesses are “conditions that last a year or more and require ongoing medical attention and/or limit activities of daily living (Hwang et al., 2001, p. 268). From a nursing perspective, “chronic illness is the irreversible presence, accumulation, or latency of disease states or impairments that involve the total human environment for supportive care and self-care, maintenance of function and prevention of further disability” (Curtin & Lubkin, 2006, pp. 6-7). Chronic disorders and acute illness cannot really be separated, because so many conditions are intricately intertwined; acute disorders have chronic sequelae, and many of the commonly identified chronic disorders tend to flare up intermittently into acute problems and then to go into remission.

A chronic illness continues indefinitely, is managed rather than cured, and necessitates that the individual “learn to live with it” (Lundman & Jansson, 2007, p. 109). By definition, it is always present although not always visible. If not triggered by an acute event, the onset may be insidious and identified only during a health screening. Symptoms of the effects of the illness, including disabilities, may not appear for years. For example, the person with hypertension develops enough heart damage to cause an acute episode of heart failure.

The person with a chronic illness may have episodic exacerbations or remain in remission with no symptoms for a long time. People with chronic illnesses often continue to work and perform their usual activities early in their diseases. Later, and with increasing age, the effects of the limitations increase. Many elders have several chronic disorders simultaneously (comorbidities) and have great difficulty managing the complexity of the overlapping and often contradictory demands.

Symptoms of chronic illness interfere with many normal activities and routines, make medical regimens necessary, disrupt patterns of living, and frequently make it necessary for the individual to make significant lifestyle changes. Physical suffering, loss, worry, grief, depression, functional impairment, and increased dependence on family or friends for support are among the negative consequences of chronic illnesses. One of the greatest fears of older people is being dependent on others as a result of chronic illness (Zauszniewski et al., 2007).

Chronic illness and aging

Many factors influence the rapid rise in the number of individuals with chronic illnesses including the aging of the population, advances in medical sciences in extending the life span and in treating illness, a rise in conditions such as asthma and diabetes, and obesity in younger people. Additional factors include the changing trajectory of illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, cancer, and dementia which are becoming chronic illnesses to live with for extended periods of time, and less than adequate prevention and health promotion efforts across the life span, particularly for diverse populations.

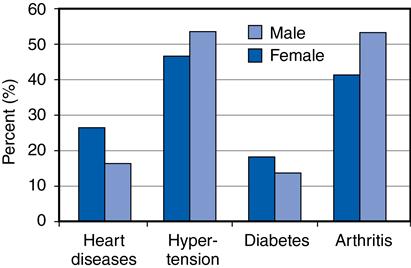

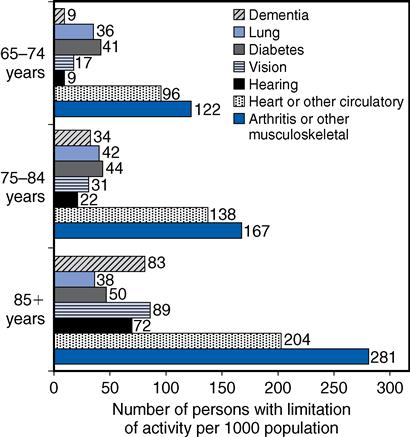

Chronic illnesses are common among older adults. About 88% of older adults have at least one chronic illness, and 50% have at least two (Zauszniewski et al., 2007). By the time a person has lived 50 years, he or she is likely to have at least one chronic condition. It may be slight arthritis at the site of an old football injury, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, or any one of a number of illnesses. The most common chronic condition for all ages is sinusitis, whereas for persons older than 65 years of age, the most common chronic conditions are arthritis and hypertension (Figure 14-1). For the older adult, the presence or absence of a chronic illness is not as important as its effect on one’s functioning. The effect may be as little as an inconvenience or as great as an impairment of one’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (Figure 14-2).

The term compressed morbidity proposes that premature death will be minimized, and disease and functional decline will be compressed into a period of three to five years before death. There is some evidence that this is already occurring because major diseases such as arthritis, arteriosclerosis, and respiratory problems now appear 10 to 25 years later than for past cohorts (Fries, 2002; Hooyman & Kiyak, 2011). The current generation of older people is generally healthier than earlier cohorts, and rates of disability are declining or stabilizing (Manton et al., 2008). Future cohorts of older people may be healthier and more functional well into their eighties and nineties, but the obesity epidemic has the potential to reduce these gains. However, rates of disability and chronic illness continue to be higher among racially and ethnically diverse older adults and need continued attention (see Chapter 4). Key strategies for improving the health of older people are presented in Box 14-1.

Prevention

Research has shown that chronic illness and poor health are not inevitable consequences of aging. Many chronic illnesses are preventable through lifestyle choices or early detection and management of risk factors. Risk factors for chronic illness begin early in life and continue through adulthood so a life span approach is essential. Health promotion activities and attention to healthy lifestyle habits throughout life can postpone and reduce morbidity for older people.

Four modifiable health risk behaviors: lack of physical activity, poor nutrition, tobacco use, and excessive alcohol consumption are responsible for much of the illness, suffering, and early death related to chronic diseases (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012). Exciting research in the field of epigenetics is leading to new understanding of the effect of environmental factors and lifestyle habits such as diet, stress, smoking, and prenatal nutrition on life expectancy for individuals and their children (see http://ww.epigenome.org/). Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012) recognizes this and includes attention to the effect of early life factors, together with late life factors, on health outcomes.

Wellness in chronic illness

High-level wellness is an integrated method of functioning that maximizes the individual’s unique potential (Dunn, 1972). Physical manifestations of chronic illness are often multiple and serious but need not kill the spirit or define the person. The wellness approach suggests that every person has an optimal level of functioning to achieve a good and satisfactory existence (well-being). Even in chronic illness and dying, an optimum level of wellness and well-being is attainable for each individual.

Theoretical frameworks for chronic illness

Several theoretical frameworks have been used to understand the effect of chronic illness and organize the nurse’s response to calls from persons with chronic illness: the Chronic Illness Trajectory (Strauss & Glaser, 1975; Corbin & Strauss, 1992), and the Shifting Perspectives Model (Paterson, 2001).

Chronic illness trajectory

The trajectory model, originally conceptualized by Anselm Strauss and Barney Glaser (1975) and later Corbin and Strauss (1992), has long aided health care providers to better understand the realities of chronic illness and its effect on individuals. According to this theoretical approach, chronic illness can be viewed from a life course perspective or along a trajectory trace. In this way, the course of a person’s illness can be viewed as an integral part of their lives rather than an isolated event. The nurse’s response is then holistic rather than isolated. Woog (1992) divided Glaser and Strauss’ model into eight phases for the purpose of identifying goals and developing interventions (Table 14-1). The shape and stability of the trajectory is influenced by the combined efforts, attitudes, and beliefs held by the older person, family members, and significant others, and the involved health care providers. Key points of the model are presented in Box 14-2.

TABLE 14-1

The Chronic Illness Trajectory

| Phase | Definition |

| Before the illness course begins, the preventive phase, no signs or symptoms present Signs and symptoms are present, includes diagnostic period Life-threatening situation Active illness or complications that require hospitalization for management Controlled illness course/symptoms Illness course/symptoms not controlled by regimen but not requiring or desire hospitalization Progressive decline in physical/mental status characterized by increasing disability/symptoms Immediate weeks, days, hours preceding death | |

Examples of goals that nurses might establish include the following:Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |