Drugs Used for Diuresis

Objectives

1 Cite the nursing assessments used to evaluate a patient’s state of hydration.

3 Cite nursing assessments used to evaluate renal function.

6 Identify the action of diuretics.

Key Terms

aldosterone ( ) (p. 457)

) (p. 457)

tubule ( ) (p. 457)

) (p. 457)

loop of Henle ( ) (p. 461)

) (p. 461)

orthostatic hypotension ( ) (p. 462)

) (p. 462)

electrolyte imbalance ( ) (p. 462)

) (p. 462)

hyperuricemia ( ) (p. 462)

) (p. 462)

Drug Therapy with Diuretics

Actions

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

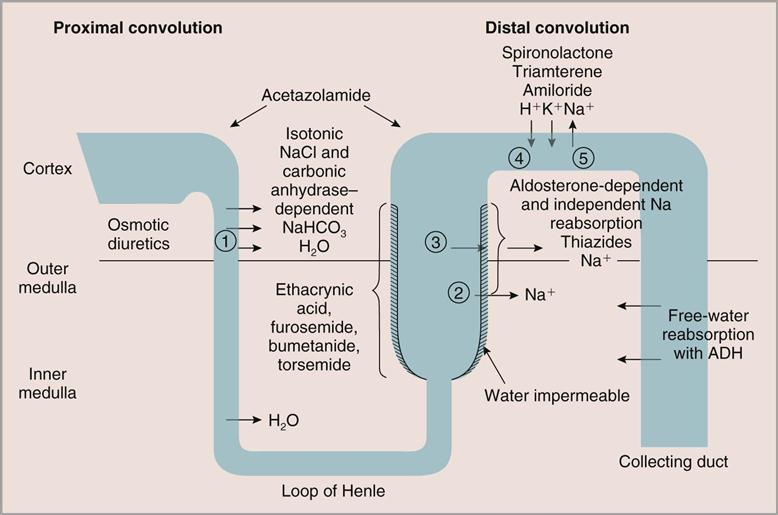

Diuretics are drugs that act to increase the flow of urine. The purpose of diuretics is to increase the net loss of water. To achieve this, they act on the kidneys in different locations to enhance the excretion of sodium. The methylxanthines increase glomerular filtration, spironolactone inhibits tubular reabsorption of sodium by inhibiting aldosterone, and thiazides and loop diuretics act directly on the kidney tubules to inhibit the reabsorption of sodium and chloride from the lumen of the tubule. Sodium and chloride that are not reabsorbed are excreted into the collecting ducts and then into the ureters to the bladder, taking large volumes of water to be excreted from the body through urination (Figure 29-1).

Uses

Diuretics are mainstays of treatment in two major diseases affecting the cardiovascular system, heart failure and hypertension. They are routinely used for patients with heart failure to remove excessive sodium and water to relieve symptoms associated with pulmonary congestion and edema. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) recommends that, after lifestyle modifications, diuretics (often in addition to other antihypertensive agents) should be used as primary agents to treat hypertension, because they have been shown to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with hypertension.

Diuretics have a variety of other medical uses as well. Mannitol reduces cerebral edema, acetazolamide is used to reduce intraocular pressure associated with glaucoma, spironolactone can be effective in reducing ascites associated with liver disease, and furosemide may be used to treat hypercalcemia.

Nursing Implications for Diuretic Therapy

Nursing Implications for Diuretic Therapy

The information the nurse obtains about the patient’s general clinical symptoms is important to the health care provider when analyzing data for the diagnosis and success of therapy. In addition to assessing overall clinical symptoms, the nurse should include the following data for subsequent evaluation of the patient’s response to prescribed therapeutic modalities that act on the urinary system.

Assessment

History of Related Causative Disorders and Factors.

Ask the patient questions relating to any history of disorders that contribute to fluid volume excess: heart disorders (e.g., myocardial infarction, heart failure, valvular disease, dysrhythmias); liver disease (e.g., ascites, cirrhosis, cancer); renal disease (e.g., renal failure); and factors such as immobility, hypertension, pregnancy, and use of corticosteroid agents.

History of Current Symptoms.

Ask the patient questions to ascertain information relating to the onset, duration, and progression of specific symptoms relating to edema, weakness, fatigue, dyspnea, productive cough, and weight gain.

Pattern of Urination.

Ask the patient to describe his or her current urination pattern and to cite any changes. Details such as frequency, dysuria, incontinence, changes in the stream, hesitancy when starting to void, hematuria, nocturia, and urgency are all significant. Provide assistance with voiding for people with impaired mobility, fatigue, or other impairments.

Medication History.

Obtain information from the patient about all prescribed and over-the-counter medications being taken. Tactfully ask questions about adherence to the medication regimen.

Hydration Status.

Obtain the patient’s baseline vital signs. Note a pulse that is bounding and full or irregular (i.e., indicating possible dysrhythmias); check the respiratory rate and quality; listen to the lung sounds to detect the presence of crackles; ask the patient about a history of recent weight gain or loss; assess for edema of the extremities; and assess for neck vein distention. Blood pressure may also be elevated.

Dehydration.

Assess, report, and record significant signs of dehydration in the patient. Observe for inelastic skin turgor, sticky oral mucous membranes, a shrunken or deeply furrowed tongue, crusted lips, weight loss, deteriorating vital signs, soft or sunken eyeballs, weak pedal pulses, delayed capillary filling, excessive thirst, a high urine specific gravity (or no urine output), and possible mental confusion.

Skin Turgor.

Check the patient’s skin turgor by gently pinching the skin together over the sternum, on the forehead, or on the forearm. Elasticity is present when the skin rapidly returns to a flat position in the well-hydrated patient. In dehydrated patients, the skin will remain in a peaked or pinched position and return very slowly to the flat, normal position.

Skin turgor is not a reliable indicator in older adults because of the natural aging changes of the skin (see Assessments under “Dehydration.”)

Oral Mucous Membranes.

With adequate hydration, the membranes of the mouth feel smooth, and glisten. With dehydration, they appear dull and are sticky. Assess skin turgor, oral mucosa, and firmness of eyeballs.

Laboratory Changes.

The patient’s hematocrit, hemoglobin, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), osmolality, and electrolytes will appear to fluctuate, based on the state of hydration. When the patient is overhydrated, the values appear to drop as a result of hemodilution. A dehydrated patient will show higher values because of hemoconcentration.

Overhydration.

Increases in abdominal girth, weight gain, neck vein distention, and circumference of the medial malleolus indicate overhydration. Daily measurements should be obtained of the patient’s abdominal girth at the umbilical level, and the extremities bilaterally at a level approximately 5 cm above the medial malleolus. The development of crackles during lung auscultation is also a sign of overhydration, especially in patients with heart failure. Weigh the patient daily using the same scale, at the same time of day, with the patient wearing similar clothing.

Edema.

Edema is a term used to describe excess fluid accumulation in the extracellular spaces. Edema is considered “pitting” when an indentation remains in the tissue after pressure is exerted against a bony part, such as the shin, ankle, or sacrum. The degree is usually recorded as +1 (slight) to +4 (deep).

Pale, cool, tight, shiny skin is another sign of edema. Also listen to lung sounds to detect the presence of excess fluid (crackles).

Assess for the presence of edema and record the degree of pitting. Obtain a baseline measurement of abdominal girth when edema is present, and check for the presence of fluid waves in the abdomen.

Electrolyte Imbalance.

Because the symptoms of most electrolyte imbalances are similar, the nurse should obtain information related to changes in the patient’s mental status (i.e., alertness, orientation, confusion), muscle strength, muscle cramps, tremors, nausea, and general appearance.

Susceptible People.

Those who are particularly susceptible to the development of electrolyte disturbances frequently have a history of renal or cardiac disease, hormonal disorders, or massive trauma or burns or are receiving diuretic or steroid therapy. Review the patient’s available electrolyte studies.

Hypokalemia.

This is indicated by a serum potassium (K+) level of less than 3.5 mEq/L. Hypokalemia is especially likely to occur when a patient exhibits vomiting, diarrhea, or heavy diuresis. All diuretics, except the potassium-sparing type, are likely to cause hypokalemia.

Hyperkalemia.

This is indicated by a serum potassium (K+) level of more than 5.5 mEq/L. Hyperkalemia occurs most commonly when a patient is given excessive amounts of potassium supplementation, either intravenously or orally. It may also occur as an adverse effect of potassium-sparing diuretics or with renal disease.

Hyponatremia.

This is indicated by a serum sodium (Na+) level of less than 135 mEq/L. Remember the following phrase: “Where sodium goes, water goes.” Because diuretics act by excreting sodium as well as water, monitor the patient for hyponatremia during and after diuresis.

Hypernatremia.

This is indicated by a serum sodium (Na+) level of more than 145 mEq/L. Hypernatremia occurs most frequently when a patient is given intravenous (IV) fluids in excess of the fluid excreted.

Implementation

Intake and Output.

I&O should be recorded accurately every shift and totaled every 24 hours for all patients having renal evaluations or receiving diuretics. Remember to administer diuretics in the morning whenever possible to prevent nocturia. Measure abdominal girth every shift, record degree of edema present in legs every shift, and obtain a daily weight.

Intake.

Measure and record accurately all fluids taken (e.g., oral, parenteral, rectal, via tubes). Ice chips and foods such as gelatin that turn to a liquid state must be included. Irrigation solutions should be carefully measured so that the difference between what is instilled and what is returned can be recorded as intake.

Remember to enlist the help of the patient, family, and other visitors in this process. Ask them to keep a record of how many glasses or cups of liquids (e.g., water, juice, soda, tea, coffee) are consumed. The nurse then converts the household measurements to milliliters.

Nutrition.

Patients with edema are routinely placed on a restricted sodium diet to help control edema associated with heart failure. Depending on the type of diuretic prescribed (potassium-sparing or non–potassium-sparing), the patient may be placed on potassium restrictions or potassium supplements.

Diet therapy for renal disease is directed at keeping a normal equilibrium of the body while decreasing the excretory load on the kidneys. See a nutrition text for modifications specific to acute and chronic renal failure.

Output.

Record all output from the mouth, urethra, rectum, wounds, and tubes (e.g., surgical drains, nasogastric tubes, indwelling catheters). Liquid stools should be recorded according to consistency, color, and quantity. Urine output should include information on quantity, color, pH, odor, and specific gravity.

All other secretions should be characterized by color, consistency, volume, and changes from previous collections, if possible.

Daily output is usually 1200 to 1500 mL, or 30 to 50 mL/hr for the adult patient. Always report urine output below this hourly rate. Low hourly output may indicate dehydration, renal failure, or cardiac disease.

Keep the urinal or bedpan readily available. Tell patients and their visitors the importance of not dumping the bedpan or urinal. Instruct them to use the call light and allow the hospital personnel to empty and record all output.

Renal Diagnostics.

Many laboratory tests are ordered throughout the treatment of renal dysfunction (e.g., BUN, serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, serum osmolalities, urine osmolalities). Plan schedules for appropriate timing of collections of blood and urine samples.

Serum Electrolytes.

Monitor serum electrolyte reports; notify the health care provider of deviations from normal values.

Nutrition.

Order a prescribed special diet, depending on the underlying pathologic condition. If fluid restrictions are prescribed, state the amount of fluid to be taken on each tray and the amount that may be taken orally each shift on the Kardex or in the computer, and have this information posted at the head of the patient’s bed.

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Purposes of Diuresis

Medication Considerations

Nutrition

Fostering Health Maintenance

Written Record.

Enlist the patient’s aid in developing and maintaining a written record of monitoring parameters (see Patient Self-Assessment Form for Diuretics or Antibiotics on the ![]() Evolve website). Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions prescribed.

Evolve website). Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions prescribed.

Drug Class: Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitor

Actions

Acetazolamide is a weak diuretic that acts by inhibiting the enzyme carbonic anhydrase in the kidney, brain, and eye. As a diuretic, it promotes the excretion of sodium, potassium, water, and bicarbonate.

Uses

Acetazolamide is not used frequently as a diuretic because of the availability of more effective medications. However, it is used to reduce intraocular pressure in patients with glaucoma (Chapter 43).

Drug Class: Sulfonamide-Type Loop Diuretics

Actions

Bumetanide, furosemide, and torsemide are potent diuretics that act primarily by inhibiting sodium and chloride reabsorption from the ascending limb of the loop of Henle in the kidneys enhancing sodium, chloride, phosphate, magnesium, and bicarbonate excretion into the urine.

Furosemide also acts to increase renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate and inhibits electrolyte absorption in the proximal tubule. The maximum diuretic effect occurs 1 to 2 hours after oral administration and lasts for 4 to 6 hours. (The brand name “Lasix” is derived from “lasts six hours.”) Diuresis occurs 5 to 10 minutes after IV administration, peaks within 30 minutes, and lasts approximately 2 hours.

Bumetanide also acts by increasing renal blood flow into the glomeruli and inhibiting electrolyte absorption in the proximal tubule. Its diuretic activity starts 30 to 60 minutes after oral administration, peaks within 1 to 2 hours, and lasts 4 to 6 hours. Following intravenous injection, diuresis begins within minutes and reaches maximum levels in 15 to 30 minutes.

Torsemide does not appear to affect glomerular filtration rate or renal blood flow. Maximum diuretic effect occurs 1 to 2 hours after oral administration and lasts 6 to 8 hours. Diuresis occurs 5 to 10 minutes after IV administration, peaks within 60 minutes, and lasts up to 6 hours.

Uses

Bumetanide, furosemide, and torsemide are used to treat edema resulting from heart failure, cirrhosis of the liver, and renal disease, including nephrotic syndrome. Furosemide and torsemide may also be used for the treatment of hypertension, alone or in combination with other antihypertensive therapy. Furosemide is also used in combination with 0.9% sodium chloride infusions to enhance the excretion of calcium in patients with hypercalcemia and to treat edema and heart failure.

Therapeutic Outcome

The primary therapeutic outcome associated with sulfonamide loop diuretic therapy is diuresis, with reduction of edema and improvement in symptoms related to excessive fluid accumulation. Reduction of blood pressure is an outcome also expected of furosemide and torsemide.

Nursing Implications for Sulfonamide-Type Loop Diuretics

Nursing Implications for Sulfonamide-Type Loop Diuretics

Premedication Assessment

Availability

See Table 29-1.

![]() Table 29-1

Table 29-1

Sulfonamide-Type Loop Diuretics

| GENERIC NAME | BRAND NAME | DOSAGE FORMS AVAILABLE | DOSAGE RANGE |

| bumetanide | — | Tablets: 0.5, 1, 2 mg Injection: 0.25 mg/mL in 2-, 4-, and 10-mL vials | 0.5-10 mg |

| furosemide | Lasix | Tablets: 20, 40, 80 mg Oral solution: 8-, 10-mg/mL IV: 10 mg/mL in 2-, 4-, and 10-mL vials | 20-400 mg |

| torsemide | Demedex | Tablets: 5, 10, 20, and 100 mg Injection: 10 mg/mL in 2- and 5-mL vials | 2-100 mg |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

)

) )

)