Natural and Man-Made Disasters

Edith B. Summerlin

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Identify the types of disasters.

2. Discuss the characteristics of disasters.

3. Describe the stages of a disaster.

4. Discuss the stages of disaster management.

5. Describe the role of federal, state, local, and volunteer agencies involved in disaster management.

6. Identify potential bioterrorist chemical and biological agents.

7. Discuss the impact of disasters on a community.

8. Describe the role and responsibilities of nurses in relation to disasters.

Key terms

American Red Cross

direct victim

disaster

disaster triage

displaced persons

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

first responders

frequency

imminence

indirect victim

mass casualty

multiple casualty

NA-TECH (natural-technological) disaster

National Incident Management System

Office of Emergency Management

predictability

preventability

refugees

resource map

risk map

shelter in place

terrorism

U.S. Department of Homeland Security

weapons of mass destruction

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

Communities throughout the world experience an emergency or disaster incident of one kind or another almost daily. The media may only mention these events or may report on them in great detail, depending on the number of dead or injured, the amount of devastation or damage to the area involved, and how much the event has disrupted normal activities within the community.

The health of a community can be affected significantly by disasters. Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita, which hit the same geographic area (U.S. Gulf Coast between Houston, Texas, and Biloxi, Mississippi) within a few weeks (September 2005), are examples of how communities and their hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, and other health care facilities are directly affected as a result of a disaster. During these hurricanes, access to health care was impeded by physical barriers, such as road closures due to flooding, inadequate numbers of first responders, and limited transportation for search and rescue. Patients were evacuated from one hospital to another, sometimes more than once. Medical and nursing personnel, medicines, and needed supplies were unavailable, scarce, or depleted because of the increased demand. Temporary shelters and health care services were established in schools, churches, and a variety of other facilities throughout the area. The wind damage and extensive flooding from Hurricane Katrina resulted in panic for food, water, and rescue in the Gulf Coast regions between New Orleans, Louisiana, and Biloxi, Mississippi. First responders and rescue teams were overwhelmed in their attempts to reach the victims.

The evacuation of Houston, Texas, and the surrounding coastal area due to Hurricane Rita created severe traffic jams, many lasting 18 to 20 hours, and resulted in travelers needing water, food, and gasoline before they reached shelter. As a result, many people suffered from dehydration and urinary tract infections. In addition, Hurricane Rita occurred during a period of record heat, and many travelers became victims of heat exhaustion caused by the high temperature and humidity. The lessons learned from these events resulted in changes in disaster plans that made a significant difference in how the next major hurricane—Ike in September 2008—was managed.

Hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, wildfires, and industrial accidents occur yearly in some parts of the United States. Further, in recent years, terrorist attacks have become more common. The bombing of the World Trade Center in New York City in 1991 and the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in 1995 occurred more than a decade ago, but the combined terrorist attacks on the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, the Pentagon in Washington, DC, and the plane hijacking and crash in Pennsylvania in 2001 indicate that the potential is ever present. Additionally, terrorist attacks occur all over the world on an almost daily basis, and concerns about potential terrorist attacks have increased the focus on what needs to be done in terms of prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery—not only in the event of terrorist attacks but also in the event of disasters of all kinds.

Because of the recognition of the need to be prepared, programs have been created to address the national, state, and local management of disasters. In March 2003, President G. W. Bush established the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and put into place the National Incident Management System (NIMS) the following year. The NIMS provides a systematic, proactive approach for all levels of governmental and nongovernmental agencies to work seamlessly to prevent, protect against, respond to, recover from, and prevent the effects of disasters (Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], 2009). Local Citizen Corps Councils have been established throughout the country to provide volunteers an opportunity to support local fire, law enforcement, emergency medical services, and community public health efforts and to contribute to the four stages of emergency management: prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery (Texas Association of Regional Councils, 2009).

Efforts to prepare for disasters have also been significantly enhanced at the state level. In Texas, for example, the Texas Legislature passed a bill requiring nurses to attend a continuing education program related to bioterrorism (Board of Nurse Examiners for the State of Texas, 2005). Further, the Ready Texas Nurses Emergency Response System (Ready Texas Nurses) was created to provide mobilization of volunteer nurses to support communities in times of crisis or disaster (Texas Department of Health and Texas Nurses Association, 2004). Similar actions are occurring throughout the country.

Nurses are uniquely positioned to provide valuable information for the development of plans for disaster prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery for communities. Nurses, as team members, can cooperate with health and social representatives, government bodies, community groups, and volunteer agencies in disaster planning and preparedness programs (i.e., drills). Nurses using their knowledge of nursing, public health, and cultural-familial structures, as well as their clinical skills and abilities, can actively assist or participate in all aspects and stages of an emergency or disaster, regardless of the setting in which the event may occur. Nurses have a significant role in meeting the health care needs of the community, not only on a day-to-day basis, but also in relation to disasters.

Disaster Definitions

A disaster is any event that causes a level of destruction, death, or injury that affects the abilities of the community to respond to the incident using available resources. Emergencies differ from disasters in that the agency, community, family, or individual can manage an emergency using their own resources. But a disaster event, depending on the characteristics of the disaster, may be beyond the ability of the community to respond and recover from the incident using their own resources. Disasters frequently require assistance from outside the immediate community, both to manage resulting issues and to recover.

Some disasters (e.g., a house fire) may affect only a few persons, whereas others (e.g., a hurricane) can impact thousands. A mass casualty event is one in which 100 or more individuals are involved; a multiple casualty event is one in which more than two but fewer than 100 individuals are involved. Casualties can be classified as a direct victim, an indirect victim, a displaced person, or a refugee. A direct victim is an individual who is immediately affected by the event; the indirect victim may be a family member or friend of the victim or a first responder. Displaced persons and refugees are special categories of direct victims. Displaced persons are those who have to evacuate their home, school, or business as a result of a disaster; refugees are a group of people who have fled their home or even their country as a result of famine, drought, natural disaster, war, or civil unrest.

Types of disasters

Disasters are identified as natural, man-made, or a combination of both. A NA-TECH (natural-technological) disaster is a natural disaster that creates or results in a widespread technological problem. An example of a NA-TECH disaster is an earthquake that causes structural collapse of roadways or bridges that, in turn, causes downed electrical wires and subsequent fires. Another example is a chemical spill resulting from a flood. Types of natural disasters and man-made disasters are listed in Box 28-1.

The American Public Health Association (2005) identified types of disasters and their consequences. Types of disasters include blizzards, cold waves, heavy snowfalls, cyclones, tornadoes, drought, earthquakes, floods, heat waves, thunderstorms, volcanic eruptions, wildfires, man-made and technological events, explosions or blasts, and epidemics. It was noted in the report that injury or death from the disaster in question may be direct or indirect. For example, injuries from hurricanes occur because people fail to evacuate or take shelter, do not take precautions in securing their property despite adequate warning, and do not follow guidelines on food and water safety or injury prevention during recovery. Drowning, electrocution, lacerations or punctures from flying debris, and blunt trauma from falling trees or other objects are some of the morbidity concerns. Heart attacks and stress-related disorders also occur. Injuries also may occur from activities in the recovery phase, for example, from use of chain saws or other power equipment or from bites from animals, snakes, or insects.

Americans are familiar with most of the disasters listed in Box 28-1, but terrorism was largely unknown or unheeded prior to the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995. The U.S. Code of Federal Regulations defines terrorism as “the unlawful use of force and violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives” (FBI, 2004). The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) defines terrorism as “the use of force or violence against persons or property in violation of the criminal laws of the United States for purposes of intimidation, coercion, or ransom” (FEMA, 2005b). The Central Intelligence Agency (2007) states that terrorism “is premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets by sub-national groups or clandestine agents, usually intended to influence an audience” (p. 2). In short, terrorists often use threats of violence, as well as acts of mass destruction, to create fear among the public, to try to convince citizens that their government is powerless, and to seek immediate publicity (FEMA, 2005b).

Acts of terrorism include threats of terrorism, assassinations, kidnappings, hijackings, bomb scares and bombings, computer-based attacks, and the use of chemical, biological, nuclear, and radiological weapons. In addition to those mentioned earlier (i.e., September 11, 2001; bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, 1995), other examples of terrorist acts include the nerve gas (sarin) attack in the Tokyo subway in March 1995, which killed 12 and injured more than 6000 people; the bombing of the commuter train in Spain in March 2004, which killed 191 people; the suicide bombing in the London subway in July 2005, which killed 52 commuters and four terrorists; and the shooting and bombing attacks in Mumbai’s financial district in November 2008, which killed more than 170.

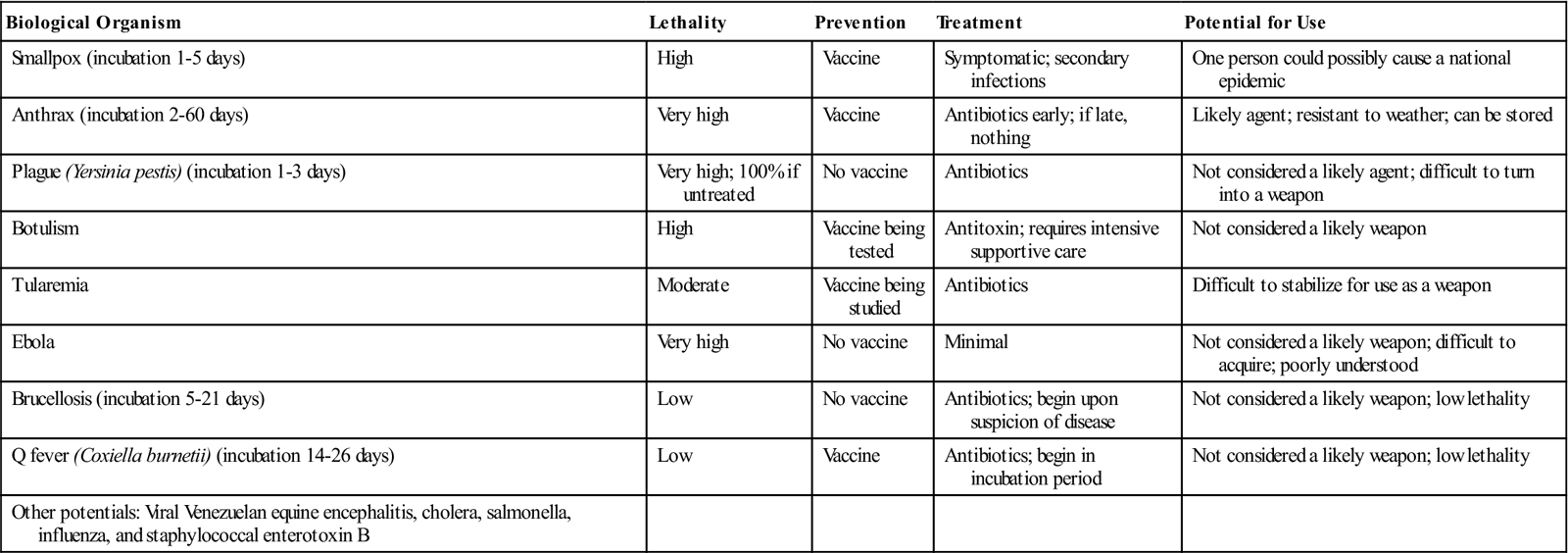

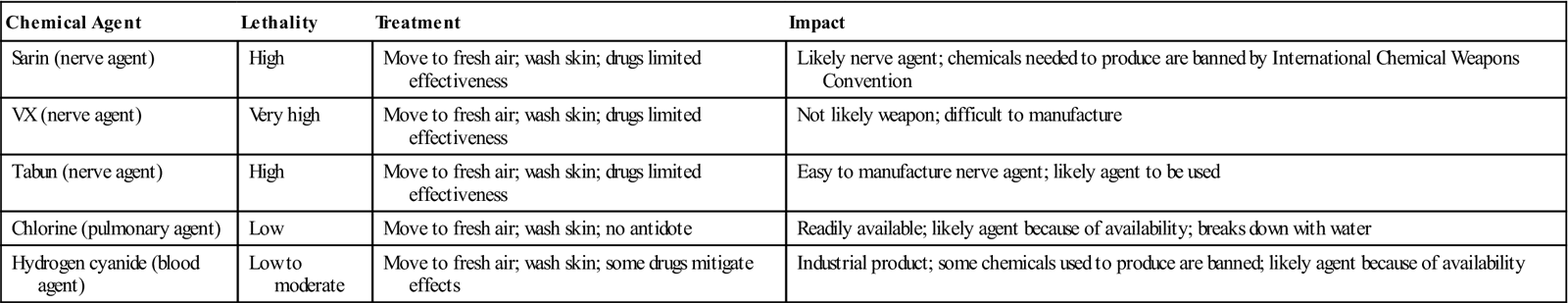

Concerns now are increasingly focused on weapons of mass destruction. Weapons of mass destruction refer to any weapon that is designed or intended to cause death or serious bodily injury through release, dissemination, or impact of toxic or poisonous chemicals, or their precursors; any weapon involving a disease organism; or any weapon that is designed to release radiation or radioactivity at a level dangerous to human life. Biological organisms considered to be potential weapons of mass destruction are found in Table 28-1, and chemicals that are potential weapons of mass destruction are listed in Table 28-2. Chemical warfare agents are classified as nerve agents, vesicants, pulmonary agents, and cyanides (formerly “blood agents”). These tables also include information about the lethality, treatment, and impact related to each.

TABLE 28-1

Biological Weapons of Mass Destruction

| Biological Organism | Lethality | Prevention | Treatment | Potential for Use |

| Smallpox (incubation 1-5 days) | High | Vaccine | Symptomatic; secondary infections | One person could possibly cause a national epidemic |

| Anthrax (incubation 2-60 days) | Very high | Vaccine | Antibiotics early; if late, nothing | Likely agent; resistant to weather; can be stored |

| Plague (Yersinia pestis) (incubation 1-3 days) | Very high; 100% if untreated | No vaccine | Antibiotics | Not considered a likely agent; difficult to turn into a weapon |

| Botulism | High | Vaccine being tested | Antitoxin; requires intensive supportive care | Not considered a likely weapon |

| Tularemia | Moderate | Vaccine being studied | Antibiotics | Difficult to stabilize for use as a weapon |

| Ebola | Very high | No vaccine | Minimal | Not considered a likely weapon; difficult to acquire; poorly understood |

| Brucellosis (incubation 5-21 days) | Low | No vaccine | Antibiotics; begin upon suspicion of disease | Not considered a likely weapon; low lethality |

| Q fever (Coxiella burnetii) (incubation 14-26 days) | Low | Vaccine | Antibiotics; begin in incubation period | Not considered a likely weapon; low lethality |

| Other potentials: Viral Venezuelan equine encephalitis, cholera, salmonella, influenza, and staphylococcal enterotoxin B |

From Cieslak TJ, Eitzen EM: Bioterrorism: agents of concern, J Public Health Manag Pract 6(4):19-29, 2000.

TABLE 28-2

Chemical Agents of Mass Destruction

| Chemical Agent | Lethality | Treatment | Impact |

| Sarin (nerve agent) | High | Move to fresh air; wash skin; drugs limited effectiveness | Likely nerve agent; chemicals needed to produce are banned by International Chemical Weapons Convention |

| VX (nerve agent) | Very high | Move to fresh air; wash skin; drugs limited effectiveness | Not likely weapon; difficult to manufacture |

| Tabun (nerve agent) | High | Move to fresh air; wash skin; drugs limited effectiveness | Easy to manufacture nerve agent; likely agent to be used |

| Chlorine (pulmonary agent) | Low | Move to fresh air; wash skin; no antidote | Readily available; likely agent because of availability; breaks down with water |

| Hydrogen cyanide (blood agent) | Low to moderate | Move to fresh air; wash skin; some drugs mitigate effects | Industrial product; some chemicals used to produce are banned; likely agent because of availability |

From Cieslak TJ, Eitzen EM: Bioterrorism: agents of concern, J Public Health Manag Pract 6(4):19-29, 2000.

Characteristics of disasters

Several characteristics have been used to describe disasters (Box 28-2). These characteristics are interdependent and therefore important to consider in plans for managing any disaster event. Each is discussed briefly.

Frequency

Frequency refers to how often a disaster occurs. Some disasters occur relatively often in certain parts of the world. Terrorist activities are occurring on an almost daily basis in Iraq and elsewhere in the world. Other examples are hurricanes, which occur with variable frequency between the months of June and November, and earthquakes, which occur periodically throughout the world. In the United States, earthquakes are generally considered to be a West Coast problem, but forty-five states and territories are at moderate to high risk for an earthquake, and earthquakes have occurred in every region of the country (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2004). Other disasters, such as volcanic eruptions, are far less frequent and are geographically limited to certain regions.

Predictability

Predictability relates to the ability to tell when and if a disaster event will occur. Some disasters, such as floods, may be predicted in the spring by monitoring the snowmelt. Weather forecasters can predict when conditions are right for the development of tornadoes; these generally occur between April and June, but they may occur at any time of the year or occur as a secondary result of hurricanes. Weather forecasters can predict hurricanes with increasing accuracy. Other disasters (e.g., fires and industrial explosions) may not be predictable at all.

Preventability

Preventability refers to actions taken to avoid a disaster. Some disasters (e.g., hurricanes, tornadoes, and earthquakes) are not preventable, whereas others can be easily controlled if not prevented entirely. For example, flooding can be controlled or prevented through construction of dams or levees or deepening bayous.

Primary prevention is aimed at preventing the occurrence of a disaster or limiting consequences when the event itself cannot be prevented. Primary prevention occurs in the nondisaster and predisaster stages. The nondisaster stage is the period before a disaster occurs, and the predisaster stage refers to action(s) taken when a disaster is pending. Preventive actions during the nondisaster stage include assessing communities to determine potential disaster hazards; developing disaster plans at local, state, and federal levels; conducting drills to test the plan; training volunteers and health care providers; and providing educational programs of all kinds.

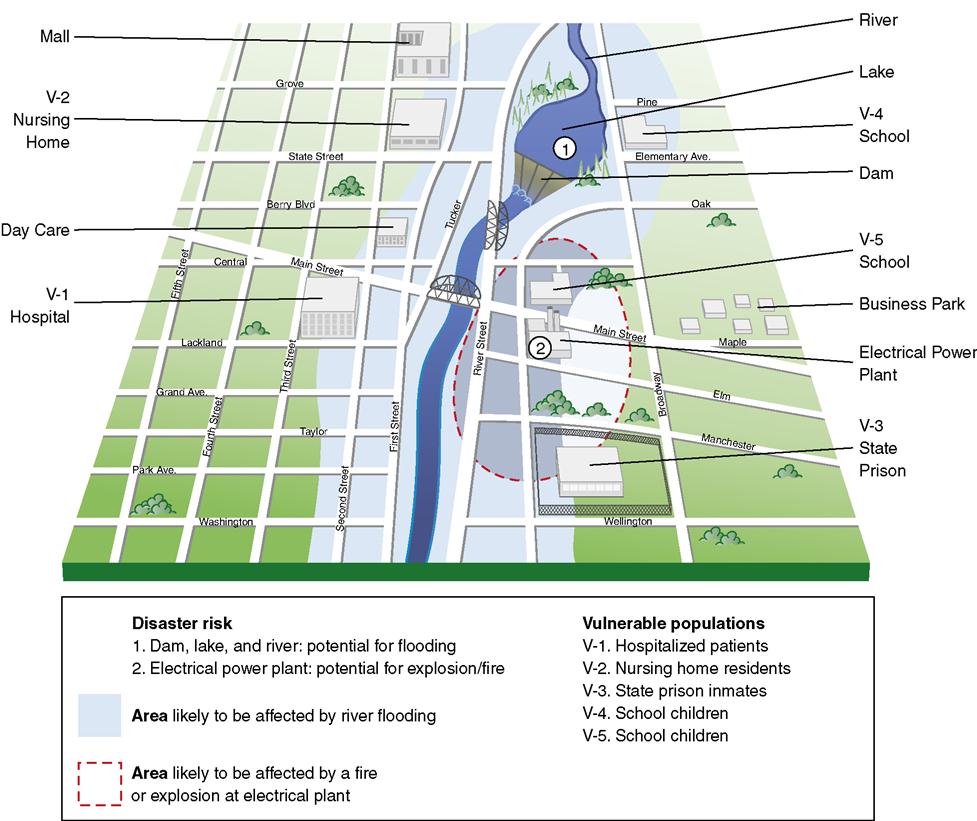

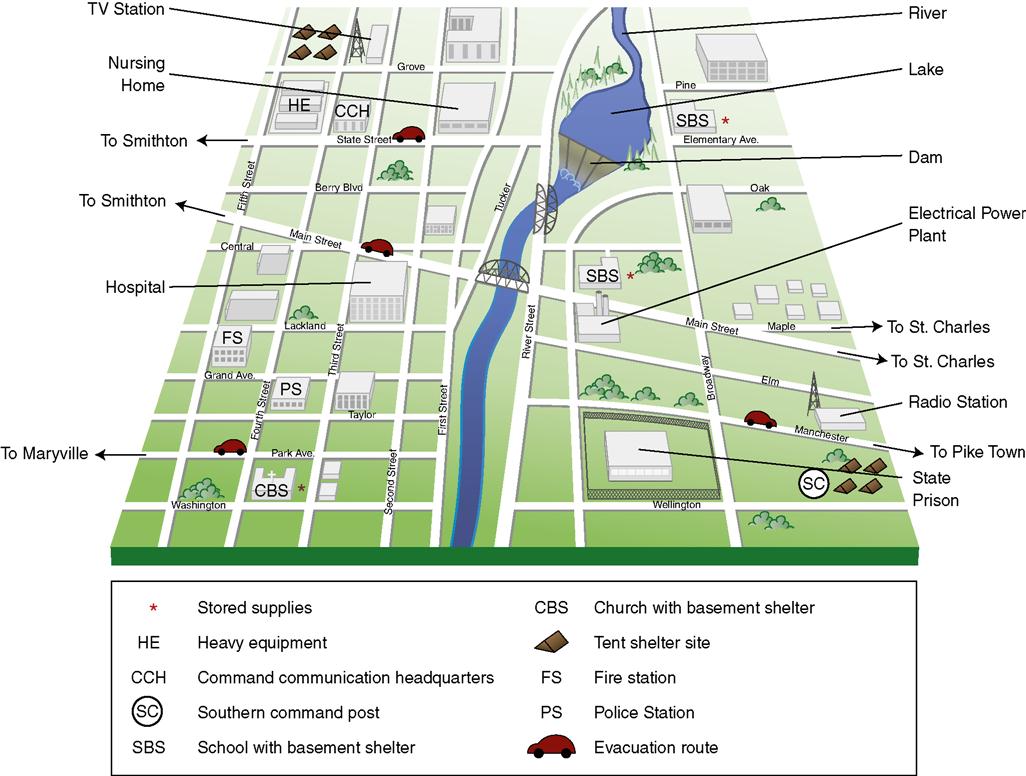

Risk maps and resource maps are developed to aid in planning. A risk map is a geographic map of an area that is analyzed for the impact of a potential disaster on the population and buildings in the area that would be involved (e.g., an area in a flood plain, an area covered if a nuclear explosion would occur, an area involved in an explosion of an industrial site) (Figure 28-1). A resource map is a geographic map that outlines the resources that would be available in or near the area affected by a potential disaster (e.g., potential shelter sites, potential medical sources, and location of equipment that might be needed) (Figure 28-2).

The disaster plan is initiated predisaster or when a disaster is imminent. Primary prevention actions during this stage include notification of the appropriate officials, warning the population, and advising what response to take (e.g., shelter in place or evacuate).

Secondary prevention strategies are implemented once the disaster occurs. Secondary prevention actions include search, rescue, and triage of victims and assessment of the destruction and devastation of the area involved.

Tertiary prevention focuses on recovery of the community, that is, restoring the community to its previous level of functioning and its residents to their maximum functioning. Tertiary prevention is aimed at preventing a recurrence or minimizing the effects of future disasters.

Nurses should be involved in all stages of prevention and related activities. In order to respond effectively, personally, and professionally during different types of disasters, nurses need to know: (1) what kind of disasters threaten their communities, (2) what injuries to expect from different disaster scenarios, (3) evacuation routes, (4) location of shelters, and (5) warning systems. They must be able to educate others about disasters and how to prepare for and respond to them. Finally, nurses need to keep up-to-date on the latest recommendations and advances in lifesaving measures (e.g., basic first aid, cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR], and use of automated external defibrillators).

Imminence

Imminence is the speed of onset of an impending disaster and relates to the extent of forewarning possible and the anticipated duration of the incident. Weather forecasters can tell when a hurricane may be developing days ahead of its expected arrival and can give the time of arrival, general direction it will take, and an approximate location for its landing and forward movement. Hurricanes, however, are subject to other weather variables and can change direction and intensity several times before actual landfall.

Some disastrous incidents (e.g., wildfires, explosions, and terrorist attacks) have no warning time. Bioterrorist attacks are generally silent, and the first awareness may be days or even weeks after exposure. For example, individuals exposed to a pathologic agent (e.g., anthrax, smallpox) may arrive at health care facilities at various times and to various providers, making diagnosis and early treatment difficult. Nurses and medical personnel need to know the signs and symptoms of biological, chemical, radiation, and nuclear exposure in order to identify the nature of the threat and then to treat and control the spread of both biological and chemical agents (see Table 28-1 and Table 28-2).

Scope and Number of Casualties

The scope of a disaster indicates the range of its effect. The scope is described in terms of the geographic area involved and in terms of the number of individuals affected, injured, or killed. From a health care perspective, the location, type, and timing of a disaster event are predictors of the types of injuries and illnesses that might occur. For example, the October 1989 earthquake in San Francisco occurred while people were on their way to work. Overall, more than 60 people died from a multitude of causes, including a motorcycle officer who was killed following the collapse of a freeway, sixteen people who were killed from building collapses, five who died as a result of falls, and nine who died of heart attacks.

In contrast, the earthquake and tsunami in October 2004 killed more than 174,000 people in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Africa; most died of drowning (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2005). Another example of the horribly destructive power of earthquakes occurred in Pakistan in October 2005. That quake resulted in landslides that killed more than 73,000 people; many of the dead were children whose schools were buried from the mudslides.

Hurricanes generally affect a large geographic area. Despite this, they may cause few if any deaths if sufficient preventive measures are taken. The scope of Hurricane Katrina in September 2005 covered all of New Orleans, most of south Louisiana, and parts of Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi. Hurricane Rita, only a few days later, struck New Orleans again, as well as south Louisiana and much of eastern Texas. Remarkably, despite the widespread destruction caused by these storms, the number of dead from Katrina was more than 1300, and the number of dead from Hurricane Rita was 58, including 23 elders who were killed in a bus accident while evacuating.

Intensity

Intensity is the characteristic describing the level of destruction and devastation of the disaster event. Factors contributing to the amount of damage from a disaster event such as a hurricane are the distance from the zone of maximum winds, how exposed the location is, building standards, vegetation type, and resultant flooding. Parts of New Orleans were under water from the primary effects (storm surge and rain) and secondary effects (levee failure) from Hurricane Katrina. Some buildings and homes were completely destroyed, and others were left in terrible conditions because of flooding and wind damage.

Various hurricane and tornado scales have been developed based on wind intensity and predicted level of destruction. The Fujita Tornado Intensity Scale developed in 1971 categorized each tornado by its intensity and the area involved. In 1992, Fujita updated the scale to include an estimate of F-scale damage. The new scale, the Enhanced Fujita Scale (EF Scale), implemented in the United States on February 1, 2007, is still a set of wind estimates (not measurements) based on types of structural damage. The estimates vary with height of apparent damage above the ground and exposure (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2009).

Hurricanes have been categorized since 1975 with use of the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, which includes sustained wind intensity, storm surge ranges, and flooding references. On an experimental basis for the 2009 tropical cyclone season, the storm surge ranges and flooding references were removed for each of the five categories (Box 28-3) because storm surge information is inaccurate. For example, Hurricane Ike in 2008 was a category 2 hurricane but had a storm surge at Galveston, Texas, equivalent to a category 4–5 storm surge, and Hurricane Katrina in 2007 was a category 3 hurricane with a storm surge equivalent to a category 5. The revised scale is called the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. The new scale does not include storm surge, rainfall-induced floods, and tornadoes. The National Weather Service is currently debating whether or not to make the change (National Weather Service, 2009).

Disaster management

When one is aware of the types and characteristics of disasters, the question then becomes: What can be done to prevent, prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters? Disaster management requires an interdisciplinary, collaborative team effort and involves a network of agencies and individuals to develop a disaster plan that covers the multiple elements necessary for an effective plan. Communities can respond more quickly, more effectively, and with less confusion if the efforts needed in the event of a disaster have been anticipated and plans for meeting them identified. The result of planning is that more lives are saved and less property is damaged. Planning ensures that resources are available and that roles and responsibilities of all personnel and agencies, both official and unofficial, are delineated.

Nurses need to know their personal, professional, and community responsibilities. They should realize that conflicts may arise between their personal and professional responsibilities if these have not been considered and planned for in advance (Ethical Insights box). Also, nurses may be direct or indirect victims and may even be displaced persons as a result of a disaster event. Recognizing this possibility, nurses need to plan, prepare, practice, and teach their family and significant others how to respond.

Local, State, and Federal Governmental Responsibilities

Local Government

The local government is responsible for the safety and welfare of its citizens. Emergencies and disaster incidents are handled at the lowest possible organizational and jurisdictional level. Police, fire, public health, public works, and medical emergency services are the first responders responsible for incident management at the local level. Local officials and agencies are responsible for preparing their citizens for all kinds of emergencies and disasters and for testing disaster plans with mock drills. They manage events during an incident by carrying out evacuation, search, and rescue and maintaining public health and public works responsibilities. Local communities should have contingency operation plans for multiple disaster situations and for various aspects of the plan. For example, landline telephone service and cell phone service may not work because of being restricted for emergency use only or damage to the infrastructure, so other forms of communication need to be available.

In an incident other than a biological, chemical, radiation, or nuclear event, in most cases, it is the 911 communication center or the fire or police department that gets the initial message. The emergency communication center then communicates the incident to the other first responders and the director of the Office of Emergency Management, who determines others who may be needed (e.g., ambulances, other officials, and voluntary group representatives). Local hospitals are notified of the incident and the predicted nature of impending casualties. The hospitals may begin to receive victims via private automobiles who have not been triaged at the site of the incident. According to the CDC, a hospital can assess the expected number of victims that it may receive by counting the number that arrive within the first hour and doubling that number.

For a biological or chemical terrorist incident, the process is very different. First responders generally are not involved. Rather, nurses and doctors in health care facilities may be the first to suspect that a biological or chemical agent has been released into the community. Box 28-4 lists the guidelines for detecting biochemical incidents. If any of these instances occurs in a health care provider setting, the suspicion should be immediately reported to the infection control department, the administration of the facility, or both. Each setting should post, near the telephone, the numbers to be called if a biochemical incident (whether internal or external) is suspected. These numbers should include those of the CDC Bioterrorism Emergency Response, the CDC Hospital Infections program, and the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (Chettle, 2001).

The Office of Emergency Management involves representatives from all official and unofficial agencies in developing the community disaster plan, developing scenarios to test the plan through drills, and assessing the scope, intensity, and number of casualties (once an incident has occurred) in order to initiate the proper response. For those events that are not within the abilities of the local community or in the event of a terrorist-type incident, higher-level agencies and resources must be requested and will become involved.

State Government

When a disaster overwhelms the local community’s resources, then the state’s Department or Office of Emergency Management is called for assistance. Prior to an event, state officials provide technical support for prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery. State officials visit local officials to assist and assess local emergency management plans, promote and conduct workshops and training courses, assist with training exercises, advise and support local government officials, and are on scene at disaster events to facilitate coordination of state resources and to disseminate information. In some cases, the National Guard may be called in to aid the community. When the scope of the event is so great that local and state resources are not adequate to meet the needs, the state calls on the federal government; at that point, the President may declare the incident a “national disaster.” Once the President declares a national disaster, federal aid is made available. At that point, the National Response Plan, the core operational plan for domestic incident management, would be initiated.

Federal Government

The policy of the federal government is to have a comprehensive and effective program in place to ensure continuity of essential federal functions across a wide array of incidents. The national strategy is to develop a system connecting all levels of government without duplicating efforts. More than 87,000 governmental jurisdictions at the federal, state, and local level have security responsibilities. All federal agencies are required to have in place a viable Continuity of Operations capability plan that ensures the performance of their essential functions during any incident that disrupts normal operations (FEMA, 2005d).

U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

As explained previously, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was established in March 2003 to realign the existing agencies, groups, and organizations into a single department, focusing on protecting the American people and their homeland. The DHS consolidated 22 agencies and their 180,000 employees into a single agency (The White House, 2005).

The mission of DHS is to: (1) lead the unified national effort to secure America, (2) prevent and deter terrorist attacks, and (3) protect against and respond to threats and hazards to the nation (DHS, 2009a). The organizational structure of the DHS contains several divisions: the Office of the Secretary, Border and Transportation Security, Emergency Preparedness and Response Directorate, Information Analysis and Infrastructure Protection, Science and Technology, Office of Management, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, U.S. Coast Guard, and the U.S. Secret Service. Within each of these divisions are multiple offices and centers (DHS, 2009b).

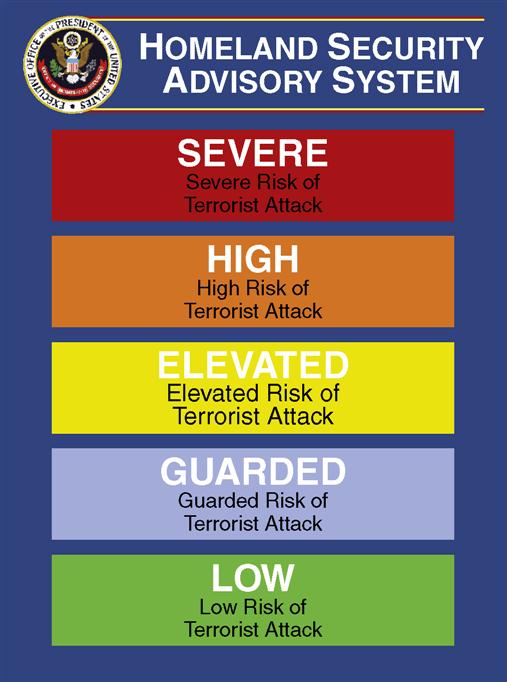

The DHS established its Homeland Security Advisory System to build a comprehensive and effective communication structure for disseminating threat information to public safety officials and the public at large. The color-coded threat level system communicates using a threat-based system of low risk to severe risk so that protective measures can be implemented to reduce the likelihood or impact of an attack. Figure 28-3 shows the five different risk levels. The actions to take build on what is done at the low-risk or green level (e.g., develop a family emergency plan) to monitoring local emergency management officials and the media for specific measures to take at the severe-risk or red level (e.g., evacuate).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ethical insights

Ethical insights