Violence

Cathi A. Pourciau and Elaine C. Vallette*

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Describe the concepts of interpersonal and community violence.

2. Identify factors that influence violence.

4. Describe the role of the nurse in primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of violence.

Key terms

child abuse

date rape drugs

dating violence

elder abuse

emotional abuse

emotional neglect

hate crimes

intentional injuries

interpersonal violence

intimate partner violence (IPV)

physical abuse

physical neglect

prison violence

sexual abuse

shaken baby syndrome

stalking

terrorism

violence

workplace violence

youth-related violence

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

A mentally unstable young man killed thirty-two people, wounded many others, and committed suicide on a college campus. A young woman who complained to the police about being stalked was killed when she opened a package delivered to her apartment. A heavily armed truck driver killed five girls in an Amish schoolhouse before killing himself. A mentally ill mother drowned her five children in the bathtub. A young male tracked down a former girlfriend through the Internet and sent hundreds of violent and threatening e-mails.

Two adolescent males ambushed their high school classmates with guns, killing thirteen and wounding many others before they killed themselves. A black male was dragged to death by five white supremacists. Two men bombed a federal building to retaliate for perceived governmental injustices. Nineteen terrorists hijacked four planes, intentionally crashing two of them into the World Trade Center’s twin towers, a third into the Pentagon, and the fourth into an empty field in Pennsylvania, killing a total of 2974 people from 90 different countries.

Violence is a national public health problem. The purpose of this chapter is to explore the influence of violence from a public health perspective as it relates to individuals and communities. Included in this chapter are discussions of the effects of violence in terms of homicides and suicides; death and injury from use of firearms; the direct influence of violence on individuals and communities; public health interventions to reduce violence; the roles and responsibilities of the community health nurse in dealing with those experiencing violence; and measures to increase awareness of violence in the workplace. An in-depth look at the causes, effects, interventions, and measures to increase awareness of violence is presented.

Overview of violence

Violence is the intentional use of physical force against another person or against oneself, which results in or has a high likelihood of injury or death. In public health, injuries from violence are referred to as intentional injuries. Violence threatens the health and well-being of people of all ages across the globe. Worldwide, 1.6 million people lose their lives as a result of violence, and it is among the leading causes of death among people aged 15 to 44 years (World Health Organization, 2009). In 2005, in the United States, more than 18,000 people were victims of homicide and more than 32,000 people committed suicide. Many more people survive acts of violence and are left with emotional and/or physical scars (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2009).

The reasons for the high rate of violence in society are highly complex. Universally recognized factors that contribute to violence include:

History of violence

Violence is not limited to present day or to the United States. Since the beginning of time, humans have dealt violently with other humans. In the Bible, Cain killed his brother Abel out of jealousy and anger. Throughout history, sporting events often resulted in death for the audience’s pleasure, such as the gladiators in Rome. Infanticide, or the killing of unwanted newborn children, has been practiced throughout history. For example, children were left to die of exposure when they were born a female, a twin, sickly, or deformed. Children, especially firstborn children, were often sacrificed for religious reasons. Infanticide was not condemned until early in the fifth century; however, this did not protect children in many societies. Children were considered to be the property of the father, and he could do whatever he wanted with them (Campbell and Humphreys, 1993).

Throughout the ages, corporal punishment has been used as a means of controlling children. Biblical reference to corporal punishment has often been used as justification for some types of child abuse. To some parents, “spare the rod and spoil the child” (Proverbs 13:24) implies an imperative to abusively discipline an errant child. The idea of “beating some sense into him” was considered necessary to ensure that a lesson was learned. In 1874, the first legal protection against child abuse in the United States occurred when the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals intervened to protect an 8-year-old girl. As a result of the notoriety associated with this case, the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children was organized later that year (Campbell and Humphreys, 1993).

Even nursery rhymes that adults read to small children seem to condone violence against them. Consider the following Mother Goose nursery rhyme:

There was an old woman who lived in a shoe,

She had so many children she didn’t know what to do,

She gave them some broth without any bread,

And whipped them all soundly and sent them to bed.

Wife beating was legal in the United States until 1824. Wives were seen as their husbands’ chattel and could be beaten for such offenses as “nagging too much.” In fact, the common phrase “rule of thumb” was derived from English law that allowed a man to beat his wife with a cane no wider than his thumb. Biblical interpretation of “wives be subject to your husband” (Ephesians 5:22) still provides some males with a faulty rationalization for wife beating. Some cultures and religions still allow, and even support, abuse of wives.

The silence that long surrounded domestic violence is derived from a historical perspective of women as their husbands’ property. The problem of assault against women was not explored in America until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. In fact, marital rape was not considered an offense in the United States until 1980. In the last two decades, additional cultural issues have surfaced in the United States regarding domestic abuse that includes female circumcision and genital mutilation, abuse between gay partners, and the realization that men are also victims of domestic violence.

Elder abuse is also a problem that is not new. The problem is of greater magnitude now because people are living longer, resulting in increased numbers of dependent and vulnerable adults. Elder abuse frequently goes undetected because of a lack of awareness on the part of health care professionals and society. The exact prevalence of elder abuse is unknown because reporting is not mandatory in all states.

Interpersonal violence

Homicide and Suicide

In the United States, homicide claimed the lives of 18,124 individuals in 2005, making it the fifteenth leading cause of death. Sixty-eight percent of these were firearm-related homicide deaths (CDC, 2009a). Young people, women, and black and Hispanic males are at higher risk than the general population. Further, in 2005, blacks were seven times more likely to commit homicide than whites and six times more likely to be victims of homicides than whites. Most murders are intraracial with 86% of white victims being killed by whites and 94% of blacks being killed by blacks (U.S. Department of Justice [USDOJ], Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2007a).

Homicide is the third leading cause of death among females in the age groups of 1 to 4 and 15 to 24 years, is the fourth leading cause of death in the 10- to 14-year age group, and ranks fifth in both the 5- to 9-year and 25- to 34-year age groups. Black females are more likely to be victims than white females, but among all females, homicide ranks in the top five causes of death among ages 1 to 34 years. Notably, approximately 30% of female murder victims are killed by an intimate partner, whereas only 5% of male murder victims were killed by an intimate partner (USDOJ, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2007b).

Homicide is the second leading cause of death among Americans aged 15 to 24 years and the fourth leading cause of death among ages 5 to 14 years. For black males aged 15 to 34 years, it is the leading cause of death and the second leading cause of death among black males aged 1 to 4 and 10 to 14 years, compared with white males, where homicide is the third leading cause of death in ages 15 to 34 years (CDC, 2005). In the past several decades, the only major cause of childhood death that has significantly increased is homicide (Finkelhor and Ormord, 2001).

Often ignored or overlooked, suicide is the eleventh leading cause of death for all Americans. More people die of suicide than of homicide in the United States; suicide took the lives of 32,637 people in 2005. It affects virtually all ages. For people between the ages of 15 and 34 years, suicide is the second leading cause of death, and it is the third leading cause of death in people aged 10 to 24 years. White males commit suicide at a rate almost double that of black males and more frequently than black or white females. In Native Americans and Alaska Natives, suicide is the second leading cause of death in ages 10 to 34 years and ranks eighth in all age groups. People of Asian or Pacific Island descent also have a high suicide rate in ages 10 to 44 years, with an overall suicide ranking of nine. Among men, 58% of all suicides in 2005 were committed with a firearm.

In women, the leading method of suicide was poisoning (39%) followed by the use of firearms (31%) (CDC, 2005). Not surprisingly, research indicates that suicidal individuals are more likely to kill themselves if a gun is in the home (Kellerman et al., 1992). Women with a history of sexual assault are more likely to attempt or commit suicide than other women. Studies show that women who attempt suicide are more likely to have been physically abused by intimate partners and are more likely to have posttraumatic stress disorder.

Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV), formerly known as domestic violence, is a pattern of coercive behaviors perpetrated by someone who is or was in an intimate relationship with the victim, such as a spouse, ex-spouse, boyfriend or girlfriend, ex-boyfriend or ex-girlfriend, or date. These behaviors may include battering resulting in physical injury, psychological abuse, and sexual assault that contributes to progressive social isolation and intimidation of the victim. Abuse is typically repetitive and often escalates in frequency and severity. IPV is the single greatest cause of injury to women between the ages of 15 to 24 years in the United States.

More than 4.5 million incidents of IPV occur each year. In 2004, there were 1544 deaths as a result of IPV, and 75% of these were female (CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2006). Violence may also be directed by women against women in lesbian relationships, by men against men in homosexual relationships, and by women against men.

IPV crosses all ethnic, racial, socioeconomic, and educational lines. About 22% of women and 7% of men report experiencing physical forms of IPV at some point in their lives (CDC, 2008). The following are risk factors for victims of IPV (CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2006):

Victims of IPV frequently suffer in silence and accept abuse as a transgenerational pattern of normative behavior. When children witness abuse between parents they learn that violence is a means of control.

Greater than 17 million women in the United States have been victims of attempted or completed rape, while 3% of men have been victims. In 55% of reported rapes, the women knew the perpetrator (Rape, Abuse, & Incest National Network, 2008). Women may report that they were subjected to forced intercourse when they were ill or had recently given birth. They also report forced anal intercourse and other violent sexual acts. Box 27-1 presents considerations for working with victims of violence.

Pregnancy does not exclude women from the danger of abuse. Indeed, pregnancy may increase stress within the family and provoke the first instances of battering. It is believed that during the first 4 months of pregnancy, approximately 15% of women are assaulted by their partner, and 17% of women are assaulted during the fifth through ninth months of pregnancy.

Homicide is the leading cause of death in pregnant women. Societal awareness of IPV during pregnancy is a relatively recent phenomenon; the mention of abuse during pregnancy began to appear in the literature in the 1980s. The image of a woman being battered during pregnancy shatters the idealized image of pregnancy as a time of nurturing and protection. All pregnant women should be routinely screened for abuse. Common signs of IPV in pregnancy are delay in seeking prenatal care, unexplained bruising or damage to breasts or abdomen, use of harmful substances (cigarettes, alcohol, drugs), recurring psychosomatic illnesses, and lack of participation in prenatal education (University of Michigan Health System, 2005). Violence during pregnancy can result in hemorrhage, spontaneous abortion, stillbirths, preterm deliveries, and fetal fractures (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2007).

Dating violence has become a national concern. Dating violence refers to abusive, controlling, or aggressive behavior in an intimate relationship that can take the form of emotional, verbal, physical, or sexual abuse. It happens in straight or gay relationships. Research indicates that one in eleven adolescents has been a victim of physical dating violence and that it occurs more frequently among black students than Hispanics or whites (CDC, 2006). A national study of college students found that 2.8% of women reported a completed or attempted rape within a 7-month period, and approximately 90% were committed by someone the victim knew. Furthermore, almost 16% of college women reported some form of sexual abuse during the academic year and that most of these occurred in their own living quarters (Wasserman, 2004).

Victims of dating violence are typically women aged 16 to 24 years with female peers who have been sexually victimized, show acceptance of dating violence, and have experienced a previous sexual assault. Perpetrators of dating violence are usually males with sexually aggressive peers, heavy drug or alcohol users, accepting of dating violence, prefer impersonal sex, and exhibit impulsive and antisocial tendencies (CDC, 2009b).

Dating violence can involve the use of date rape drugs, such as gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB), Rohypnol, and ketamine, to reduce inhibitions and promote anesthesia or amnesia in the victim. GHB is odorless and colorless and can easily be made at home. Instructions are available in libraries and on the Internet, which may explain the drug’s rapid rise in popularity. Although illegal in the United States, it has become popular in many nightclubs where it is available in clear liquid form. GHB has been touted as an aphrodisiac and an anesthetic. It is actually a depressant that slows down the respiratory system and has been responsible for numerous overdoses and multiple deaths. When mixed with alcohol, in particular, it can be deadly.

Rohypnol (flunitrazepam), classified as a benzodiazepine, has been compared to Quaalude, the “love drug” of the 1960s and 1970s. Like GHB, Rohypnol is not legal in the United States, but many reports have been received of its use at fraternity parties, at college gatherings, and in gay bars on both coasts. The ability to provide a quick, cheap high with long-lasting effects may explain its popularity. Combined with alcohol, serious side effects including death have been reported. Ketamine (ketamine hydrochloride) is an anesthetic used primarily in veterinary practice. It causes a lost sense of time and problems with memory. Another drug that is becoming more common as a date rape drug is Soma. It is a prescription muscle relaxant and central nervous system depressant.

Recent studies have linked alcohol, “a hallmark of college campus social life,” with dating violence. Substance abuse was implicated in 74% of sexual assaults on college campuses (Wasserman, 2004). Alcohol contributes to sexual assault because it impairs the ability to think clearly, lowers inhibitions, and impairs ability to evaluate an unsafe situation.

Stalking is a pattern of repeated and unwanted attention, contact, harassment, or any type of conduct directed at a person that instills fear. Types of stalking include messaging through the Internet or cell phone, damaging the victim’s property, following the victim, obtaining personal information about the victim, and making direct or indirect threats to the victim’s family or friends. Females are three times more likely to be stalked than males. In one 12-month period, approximately 3.4 million people reported being stalked (USDOJ, Office of Violence Against Women, 2009).

IPV is about control, not anger. The objective of abuse is to exert power and control over the victim. Victims may have been exposed to violence as a child. In these cases, the learned response is often one of helplessness that implies passivity and acceptance of abuse. Box 27-2 presents commonly held myths associated with IPV.

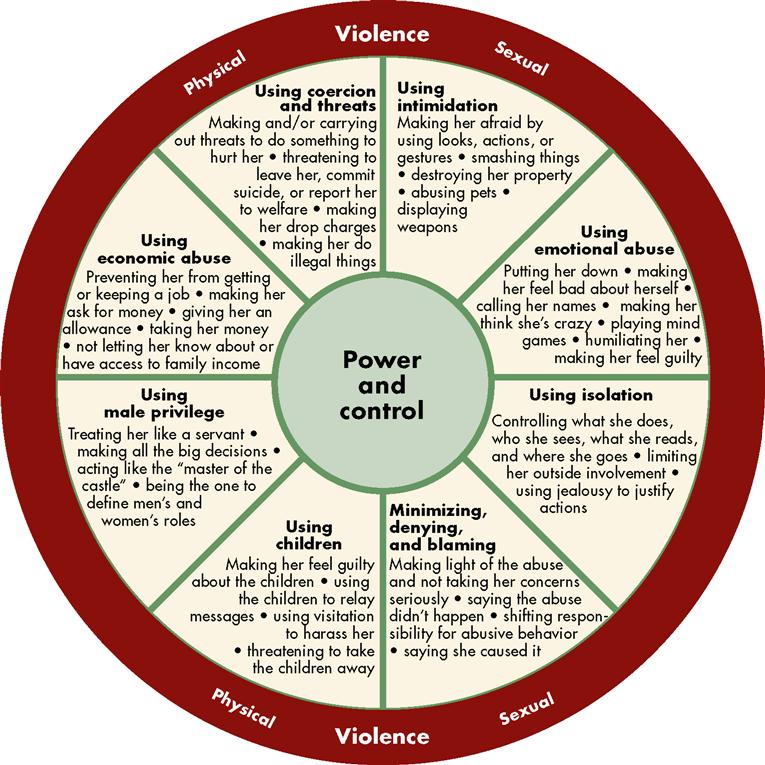

The Domestic Abuse Intervention Project in Duluth, Minnesota, has developed a wheel of violence that depicts the types of power and control that are used. These include emotional abuse and intimidation, minimization, denial and blaming, coercion and threats, isolation, economic abuse, use of children, and male privilege. Figure 27-1 depicts the power and control wheel.

Chronic stress characterizes the lives of people in relationships with violent partners. When subjected to repeated abuse, the abuse victim may experience a variety of responses including shock, denial, confusion, withdrawal, psychological numbing, and fear. Victims live in anticipatory terror and often have chronic fatigue and tension, disturbed sleeping and eating patterns, and vague gastrointestinal and genitourinary complaints. Health care providers frequently overlook or misdiagnose these obscure symptoms. In many instances, providers may label the abuse victim as hypochondriacal or clinically depressed. Few victims spontaneously disclose that they are being abused, and the failure of health care professionals to routinely assess for abuse significantly contributes to a missed diagnosis.

Fear, helplessness, and lack of knowledge regarding resources are primary reasons that many victims do not readily leave an abusive situation. The legal system is cumbersome and often inadequate. Victims who seek help through restraining orders or other judicial means find that such methods do not provide real safety or solutions. For example, after reporting abuse to the police, the partner may be jailed and given bail within 24 hours only to return home, unannounced, to deliver another beating. After attempting to use the judicial system as a solution and experiencing its failure, the victim is unlikely to consider the legal system as a source of safety. Victims may also fear that legal intervention might be a threat to custody of their children.

Other factors that keep a victim in an abusive situation are culture, religion, and economics. For example, victims with few marketable skills who leave an abusive situation face serious economic problems and may fall into poverty. When children are involved in such economically dependent relationships, the victim may choose to remain in the setting as a means of economic survival for the children. Health care providers, including nurses, often ask the victim, “Why don’t you just leave?” or “What did you do to deserve this?” These misdirected questions often reinforce the victim’s sense of helplessness and guilt regarding the abusive situation. These questions reflect a lack of understanding regarding the dynamics of abuse and a lack of sensitivity toward the victim.

Victims who are most likely to leave a battering situation include the following (Campbell and Humphreys, 1993):

1. Those who have resources, such as money, friends, family, and support

2. Those who have power (e.g., a job, credit cards, and status outside the family)

4. Those who were not abused as children

5. Those who did not see their mothers beaten

6. Those involved in battering situations that are frequent or severe

7. Those whose partner begins to beat children in the family

The most dangerous time for victims is when they leave or attempt to leave the relationship, because it is seen as an erosion of the abuser’s control. The victim is more likely to be killed at this time than at any other time in the relationship (Campbell and Humphreys, 1993).

Child Abuse

Most child abuse occurs within the family. Parents and relatives who were abused themselves are most often the perpetrators. Abuse of children is more commonly seen in families living in poverty, by teenage parents, or by parents who are drug or alcohol abusers. In some families all children are equal targets of abuse, whereas in other families a particular child may be selected as the designated recipient of abuse. The child may be singled out by a particular physical characteristic such as hair color or resemblance to another family member who evokes negative emotions in the abusive parent. Child abuse, like domestic violence, is often a learned transgenerational behavior. Although statistical reporting of child abuse is mandatory throughout the country, reported numbers are probably an underestimation. Children are not likely to report the abuse because they fear reprisal.

There were more than 900,000 (or twelve per 1000) cases of child abuse reported in the United States in 2006. Girls are more likely to be victims than boys, and women are more likely to be the perpetrator. More than 1500 children died in the United States of abuse and neglect in 2006 (CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2008). The four types of child abuse are as follows:

Physical abuse is an intentional injury inflicted on a child by another person and accounts for 16% of child abuse cases (CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2008). Parents who abuse often have unreasonable expectations of their children and may misinterpret the child’s behavior as threats to their parental self-esteem and need to control. Physical abuse includes beating, burning, biting, bruising, and head and internal injuries. The type of physical injury varies only with the adult’s imagination. Patterned injuries may give some clue as to how the child was injured. A child who touches a light cord or light plug might be beaten with it, producing a looped or linear pattern. A child who plays with matches or the stove might have his or her hand placed in the flame. A crying child or a child who talks back might have hot pepper or Tabasco sauce poured into his or her mouth or might be suffocated with a pillow.

Young children under the age of 1 year, followed by children aged 1 to 3 years, are most frequently injured by physical abuse. Infants are in the greatest danger of severe injury or death (CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2008). One example of infant abuse is shaken baby syndrome. Shaken baby syndrome, a form of inflicted head trauma, is a leading cause of death in the United States from child abuse. Most victims are between 3 and 8 months of age. In this form of abuse, violent shaking of the infant causes trauma at the junction of the brainstem and spinal cord; this can lead to death. Serious and permanent damage may also occur; this includes retinal hemorrhages, spinal cord injuries, and brain injuries. In approximately 65% to 90% of shaken baby cases, the father or the mother’s boyfriend is the perpetrator (KidsHealth, 2009).

Physical neglect is negligent treatment or maltreatment of a child by a person responsible for the child’s welfare. It is the most common form of child abuse and accounts for 64% of all cases (CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2008). Physical neglect includes the failure to provide basic needs such as shelter, food, clothing, education, and access to medical care by the responsible person. Failure to provide a nurturing environment for a child to thrive, learn, and develop and failure to provide for the health needs of a child can also be construed as neglect. Emotional neglect is the failure to nurture a child in developmentally appropriate ways. Examples of emotional neglect include failure to cuddle and/or physically stimulate a newborn, failure to give positive feedback, failure to pay attention to the overall emotional needs of a child, or failure to show affection.

Emotional abuse accounts for approximately 7% of all child abuse cases and is the behavior that may damage a child’s self-worth or emotional well-being (CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2008). The child may demonstrate a substantial impairment in behavior such as an overly compliant or passive child, a very aggressive child, or a child who is inappropriately adult or infantile. Emotionally abused children frequently do not progress at a normal rate of physical, intellectual, or emotional development. They also have an increased risk for suicide. Emotional abuse usually occurs in the home, unwitnessed by others. Emotional abuse might include name calling, such as “you’re stupid,” “you’re a slut,” “you’re bad,” or “you’re evil,” shaming, withholding love, rejection, or threatening behavior. Impairment in behavior may also occur in children who are not abused; therefore, identification is difficult.

Sexual abuse is any sexual activity between an adult and a child, including use of a child for sexual exploitation, prostitution, or pornography. Sexual abuse can also involve an older child with a younger child, usually defined as a difference of 5 or more years of age between the two. Incest is the term used for sexual relations between close family members, such as father and daughter, mother and son, or siblings. Approximately 9% of child abuse cases are sexual abuse (CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2008).

Sexual abuse often involves a person known to the child. A growing concern is the sexual exploitation of children by Internet pedophiles who prey upon unsuspecting and naive targets. It may occur over a prolonged period of time, and threats to the child may be used to ensure secrecy. Although most research has focused on females as victims of sexual abuse, males are also targets. The victim may refrain from reporting abuse because he is ashamed or because cultural values expect males to be assertive and capable of self-defense.

The aftermath of abuse may predispose the victims to low self-esteem, psychiatric illness, health problems as adults, depression, suicide ideation, drug and alcohol addiction, eating disorders, obesity, sexual maladjustment, delayed developmental processes, and prostitution (CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2008). The child may delay reporting the abuse for months or years, as it may take that long for him or her to feel safe. Table 27-1 describes physical and behavioral indicators of child abuse and neglect.

TABLE 27-1

Physical and Behavioral Indicators of Child Abuse and Neglect