Kathleen F. Jett

Loss, death, and palliative care

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

When we were in our sixties my friends and I met over cards, went on trips, and experienced all the joys of retirement. We didn’t have much time to worry about aches and pains. In our seventies we had less time to play because we were busy visiting one another in the hospital or nursing home. In our eighties we met frequently again, but it was usually at our friends’ funerals, leaving little time for cards or travel. Now that I am in my nineties hardly any of my friends are still alive; you know it gets kind of lonely, so you just have to make new younger friends!

Theresa, age 93

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Differentiate between loss and grief.

• Explain the different types of grief and the dynamics of the grieving process.

• Propose palliative measures when comfort is the goal of care.

• Explain the role and responsibility of the nurse in advance directives.

• Explain the difference between passive and active euthanasia.

Glossary

Bereavement overload A number of grief situations in a short period of time.

Euthanasia Death that is unrelated to the natural life processes or random accident.

Grief An emotional response to loss.

Mourning The process by which grief is expressed.

Palliative care Care which is directed toward maximizing comfort rather than achieving a cure.

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

Life is like a pinwheel, a thing of beauty and change. Loss, like the wind, sets it in motion, beginning the life-changing process of grieving. Throughout one’s life the winds of loss will gently stir recurrent episodes of grief through sights, sounds, smells, anniversary dates, and other triggers. The arms of the pinwheel suggest movement by the bereaved, reaching out of the experience of grief by surrendering through resting, or lowering one’s defenses toward life and being open to reality, or the acceptance of the life event and reaching out to others and rejoining life through change. Each gust of wind may generate a resurgence of grief, but the pinwheel will never lose its beauty.

Loss, dying, and death are universal, incontestable events of the human experience. Some loss is associated with the normal changes with aging, such as the loss of flexibility in the joints (see Chapter 5). Some is related to the normal changes in everyday life and life transitions, such as moving and retirement. Other losses are those of loved ones through death. Some deaths are considered normative and expected, such as older parents and friends. Other deaths are considered non-normative and unexpected, such as the death of adult children or grandchildren.

Regardless of the type of loss, each one has the potential to trigger grief and a process we call bereavement or mourning. Grieving and mourning are usually used synonymously. However, grieving is an individual’s response to a loss and mourning is an active and evolving process that includes those behaviors used to incorporate the loss experience into one’s life after the loss. Mourning behaviors are strongly influenced by social and cultural norms that prescribe the appropriate ways of both reacting to the loss and coping with it (Chow et al., 2007; Gerdner et al., 2007). For example, in much of the world, widows are expected to wear black after the death of their husbands, but in India the traditional dress is a white sari for the remainder of the time the woman remains a widow. There is no single way to grieve or respond to loss; each person grieves in his or her own way.

Although there are cultural expectations related to grief behaviors for loss through death, there are no guidelines for behavior when the loss is of another type. For example, an individual who moves to a nursing home (loses one’s home), or who retires (willingly or unwillingly) may be very sad, irritable, and forgetful. The person may be suspected of developing dementia when he or she is actually grieving. When the losses accumulate in quick succession, a state of bereavement overload may result. The griever may become incapacitated and require careful and skilled support and guidance.

Gerontological nurses need to have basic knowledge of the grieving process and how to comfort and care for grievers, including one another. Additional knowledge and skills are related to care of the dying person and his or her survivors including those needed to provide quality care. And finally nurses caring for the dying must be comfortable with their own mortality. In this chapter we hope to provide the basic information necessary to promote effective grieving, peaceful dying, and good and appropriate deaths.

The grieving process

Researchers have tried for years to understand the grieving process. Their efforts have resulted in a number of models proposed to explain and predict the experience. The majority of the models developed between the early 1970s and early 1980s influence what caregivers and society in general have been taught about grief. Although intended to describe death-related grief, these same models can be applied to any of the losses in the lives of older adults that are significant or meaningful to that person.

All models recognize similar physical and psychological manifestations of acute grief (when it is first felt), a middle period in which the manifestations of grief (e.g., despair, depression) affect the person’s day-to-day functioning, and an ending phase where the person learns to adjust to life in a new way without that which has been lost or in anticipation of their pending deaths. At the same time it is also recognized that the grieving process is not rigidly structured and that a predictable pattern of responses does not always occur.

A loss response model

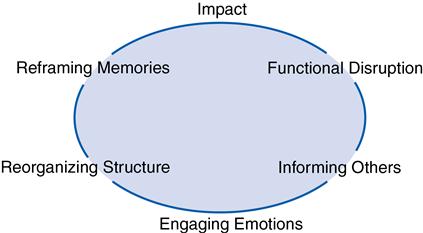

Jett’s Loss Response Model is a modification of that proposed by Barbara Giacquinta for families facing cancer (Giacquinta, 1977). It incorporates Betty Newman’s System Model (Parker & Smith, 2010) that leads to a framework for the design of nursing interventions.

When loss occurs within a system, such as a family, the impact is experienced as acute grief. The system’s equilibrium is in chaos and is seen as a functional disruption; that is, the system cannot perform its usual activities. Either the person or the members are in a state of disequilibrium. The loss seems unreal. The grieving family searches for meaning: why did this happen? How will they survive the loss? If an elder is reacting to the loss of a child or a grandchild, thoughts of “why wasn’t it me?” are common. If it is the loss of one’s health or a move out of one’s home, the question “how could this happen to me?” could arise. The family or elder then may become active in informing others. Each time the story is repeated, the loss becomes more real and the system moves toward a new steady state. The story may be different each time it is told, as it is told from a new perspective. Informing others involves engaging emotions that may have been previously withheld or subdued because of the shock of the impact. The expression of emotions can be quite powerful: anger, frustration or even relief. They can release energy that can be used to reorganize the family structure. As roles change, adaptation and accommodation are necessary. Someone else steps in to perform the roles of the person who is now absent or to complete the tasks no longer possible in the presence of the loss. For example, when the elder patriarch dies, the eldest son may step up and assume some of his father’s roles and responsibilities. Finally, if the system is to survive, it will need to redefine itself. One of the ways that it does this is by reframing its memories; that is, families accept that portraits and reunions are still possible, just different than they were before the loss; or they accept that a person can still be vital, active, and important even after the loss of the ability to drive a car, to walk unassisted, or to live alone (Figure 25-1).

Types of grief

Grieving takes enormous amounts of physical and emotional energy. It is the hardest thing anyone can do and may be especially hard for older adults who must simultaneously face other challenges discussed throughout this book. Emotions can be intense, and this intensity may manifest as confusion, depression, or preoccupation with thoughts of the deceased or the loss. This reaction may be mistaken for other conditions, such as dementia, when it probably is a type of delirium, a temporary change in mental status, something that requires careful assessment and care (see Chapter 21). The gerontological nurse is most likely to work with elders who are experiencing anticipatory grief, acute grief, or chronic grief. A fourth type, disenfranchised grief, may be hidden, but when it occurs it is nonetheless significant.

Anticipatory grief

Anticipatory grief is the response to a real or perceived loss before it actually occurs, a dress rehearsal, so to speak. One observes this grief in preparation for potential loss, such as loss of belongings (e.g., selling of a home), moving (e.g., into a nursing home), or knowing that a body part or function is going to change (e.g., a mastectomy), or in anticipation of the loss of a spouse or oneself either through dementia or through death. Behaviors that may signal anticipatory grief include preoccupation with the loss, unusually detailed planning, or a sudden change in attitude toward the thing or person to be lost (Lewis & McBride, 2004). End-of life communication has been found to be associated with anticipatory grief and improved bereavement-related outcomes (Metzger & Gray, 2008).

The grieving process described by the models may occur in the context of anticipatory grief with one significant difference: the loss has not yet occurred. If the loss is certain but no one can say when it will occur, or if it does not occur when or as expected, those awaiting the actual loss or death may become irritable, hostile, or impatient, not because they want the loss to occur but in response to the emotional ups and downs of the waiting. Researchers Glaser and Strauss (1968) described what they call an interruption in the sentimental order of a nursing unit when this occurs—no one quite knows how to behave. Professionals who are grieving, such as nurses, as well as family and friends, usually deal much more easily with anticipated losses when they occur at an expected time or in a set manner.

Anticipatory grief can result in the phenomenon of premature detachment from an individual who is dying or detachment of the dying person from the environment. Pattison (1977) called the premature withdrawal of others sociological death, and the premature withdrawal of the person, psychological death. In either case, the person who is dying is no longer involved in day-to-day activities of living and essentially suffers a premature death.

Acute grief

Acute grief is a crisis. It has a definitive syndrome of somatic and psychological symptoms of distress that occur in waves lasting varying periods of time. These symptoms may occur every time the loss is acknowledged, others are informed, or even when another person offers condolences. Preoccupation with the loss is a phenomenon similar to daydreaming and is accompanied by a sense of unreality. Depending on the situation, feelings of self-blame or guilt may be present and manifest themselves as hostility or anger toward friends, depression, or withdrawal. A formerly bad relationship may be idealized and confusing to others.

It is often difficult for persons who are acutely grieving to accomplish their usual activities of daily living or meet other responsibilities (functional disruption). Even if the tasks are accomplished, the person may complain of feeling distracted, restless, and “at loose ends.” Common, simple activities such as deciding what to wear may seem too complex a task. Fortunately the signs and symptoms of acute grief do not last forever, or else none of us could survive. Acute grief is most intense in the months immediately following the loss, especially the first 3 months, with the intensity of feelings lessening over time (Taylor et al., 2008). A griever may cry in the first months any time that which is lost is mentioned. Later, the person will still be grieving, but the tears are replaced with a surging sense of loss and sadness, and still later by more fleeting reactions.

Chronic and complicated grief

Grief may temporarily inhibit some activity but is considered a normal response. The intermittent pain of grief is often exacerbated on anniversary dates (birthdays, holidays, and wedding anniversaries). For the survivors of tragedies, such as war, the Oklahoma City bombing, the 9/11 or some other terrorist attack, the grief may never completely go away. In some cases this takes the form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and for others there is a lingering grief described as “shadow grief,” or that which resurfaces from time to time in the form of a fleeting grief response, usually triggered by a sight, smell, or sound (Coryell, 2007) (Box 25-1).

Some chronic grief is more than that of shadow grief and crosses the boundary to what we call impaired, pathological, abnormal, dysfunctional, or maladaptive grief. It has been thought that pathological chronic grief begins with normal grief responses, whose normal evolution toward adjustment, toward the reestablishment of equilibrium, is blocked by some obstacle. The memories resist being reframed. Reactions are exaggerated, and memories are experienced as recurrent acute grief—over and over again, months and years later. Signs of possible pathological grief include excessive and irrational anger, outbursts in social settings, and insomnia that lingers for an extended time or surfaces months or years later, or a grief episode that triggers a major depressive episode. The families who have had a loved one who has committed suicide have been found to be among those who have a greater risk for complicated, chronic grief (Sveen & Walby, 2008). This type of grief necessitates the professional intervention of a grief counselor, a psychiatric nurse practitioner, or a psychologist who has skills at helping grieving elders and their loved ones.

Disenfranchised grief

Disenfranchised grief is experienced by persons whose loss cannot be openly acknowledged or publicly mourned. The grief is socially disallowed or unsupported (Doka, 2002). The person does not have a socially recognized right to be perceived or function as a bereaved person. In other words, a relationship is not recognized; the loss is not sanctioned, or the griever is not recognized or cannot be made public. Disenfranchised grief has frequently been associated with domestic partnerships in which the family of the deceased does not acknowledge the partner or in secret relationships in which the involved party cannot tell others of the meaning or depth of the attachment. Disenfranchised grief can also occur in situations of family discord in which a member of the family is considered the “black sheep.” It has also been recognized in combat veterans who must integrate their own roles in killing in a war zone (Aloi, 2011). Older adults can experience this disenfranchisement when persons close to them do not understand the full meaning of the loss such as retirement or the death of a pet. Families coping with a member who has Alzheimer’s disease may also experience disenfranchised or chronic grief, particularly when others perceive the death of the elder as a blessing and fail to support the griever or caregiver who has struggled for years with anticipatory grief and now must cope with the acute grief of the actual death (Doka, 2002; Paun & Farran, 2011).

Factors affecting coping with loss

Coping as it relates to loss and grief is the ability of the individual or family to find ways to deal with the stress. In the language of the Loss Response Model, it is the ability to move from a state of chaos and disequilibrium to one of renewed order, equilibrium, and peace. Many factors affect the ability to cope with loss and grief (Box 25-2).

Those at special risk for significantly adverse effects of grief are older spouses and life partners of any kind. Intense grief may cause a temporary decrease in cognitive function that can be misinterpreted as dementia, isolating the griever (Ward et al., 2007).

A classic authority on death and dying was psychiatrist Avery Weisman (1979). He described those who are more likely to effectively deal with loss as “good copers” (p. 42). These are individuals or families who have experience with the successful management of crisis; they are resourceful and are able to draw on coping strategies that have worked in the past. Weisman (1979, pp. 42-43) found persons who cope effectively with cancer do the following:

• Confront realities, and take appropriate action

In other words, the effective copers are those who can acknowledge the loss and try to make sense of it. They are able to generally use good judgment, and are able to remain optimistic without denying the loss. These good copers seek guidance when they need it.

In contrast, those who cope less effectively have few if any of these abilities. They tend to be more rigid and pessimistic, are demanding, and are given to emotional extremes. They may be dogmatic and expect perfection from themselves and others. Ineffective copers are also more likely to be individuals who live alone, socialize little, and have few close friends or an ineffective support network. They may have a history of mental illness, or they may have guilt, anger, and ambivalence toward the individual who has died or that which has been lost. Those at risk for pathological grief will more likely have unresolved past conflicts or be facing the loss and other, secondary stressors simultaneously. They will have fewer opportunities as a result of the loss. They are the elders who are most in need of the expert interventions of grief counselors and skilled psychiatric gerontological nurse practitioners (Weisman, 1979).

Implications for gerontological nursing and healthy aging

The goal of the nurse is not to prevent grief but to support those who are grieving. Although the loss will never change, the potential long-term detrimental effects can be lessened. Working with grieving elders is part of the normal workday of gerontological nurses, who are professional grievers in our own way. It is one of the few areas in nursing where small actions can make a large difference in the quality of life for the person to whom we provide care and with whom we work.

Assessment

The goal of the grief assessment is to differentiate those who are likely to cope effectively from those who are at risk for ineffective coping, so that appropriate interventions can be planned. A grief assessment is based on knowledge of the grieving process and the subsequent mourning. Data are obtained through observation of behavior of the individual and are assessed within the context of the person’s culture (National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2006).

A thorough grief assessment includes questions about recent significant life events, life or religious values, and relationship to that which has been lost. How many other stressful or demanding events or circumstances are going on in the griever’s life? This information will help determine who is at most risk for impaired grieving. The more concurrent stressors in the person’s life, the more he or she will need the nurse or other grief specialists. The nurse determines what stress management techniques have been used in the past, and whether they were helpful (e.g., talking) or potentially harmful (e.g., substance use or abuse). Was the griever’s identity closely tied to that which is lost, such as a lifelong athlete who is faced with never walking again? If the loss is of a partner, how was the relationship? The loss of an abusive or controlling partner may liberate the survivor, who may feel guilty for not feeling the amount of grief that is expected. For many older women who have been dependent financially on their spouses, death may leave them impoverished, significantly complicating their grief. Knowing more about the loss and the effect of the loss on the elder’s life will enable the nurse to construct and implement appropriate and caring responses.

Interventions

One goal of intervention is to assist the individual (or family) in attaining a healthy adjustment to the loss experience and reestablishing equilibrium. Memories are reframed so that they can account for the loss without diminishing the value of that which has been lost thus minimizing the risk for complicated grief (Maccallum & Bryant, 2011). Actions that can meet these goals are basic and simple; however, the emotional overlay makes the simple difficult. For the new nurse who is confronted with a person’s grief for the first time, there may be discomfort, fear, and insecurity. The tendency is to be sympathetic rather than empathetic. Questions arise in one’s mind: What do I say? Should I be cheerful or serious? Should I talk about or even mention the dead person’s name?

Nursing interventions, especially when elders are in crisis, begin with the gentle establishment of rapport. Nurses introduce themselves, explain the nature of their roles (e.g., charge nurse, staff nurse, medication nurse) and the time available. If it is the time of impact (e.g., just after a new serious diagnosis, at the death of a family member, or upon becoming a new but resistant resident of a long-term care facility), the most we can do is to provide support and a safe environment and ensure that basic needs, such as meals, are met. The nurse can soften the despair by fostering reasonable hope, such as, “You will make it through this time, one moment at a time, and I will be here to help.”

Nurses observe for functional disruption and offer support and direction. They may have to help the family figure out what has to be done immediately and find ways to do it—either the nurse offers to complete the task or finds a friend or family member who can step in so the disruption does not have any deleterious effects.

As grievers search for meaning, they may need help finding what they are looking for if this is possible. Sometimes it is information about a disease, a situation, or a person. Sometimes it is a spiritual search and help in finding a source of comfort such as a priest, rabbi, or medicine person or a place of peace, such as the chapel or mosque. Often what is needed most is someone to listen to the “whys” and “hows”—questions that cannot be answered.

Sometimes nurses offer to contact others for those who are grieving, thinking that this is something that will help. However, it is far more therapeutic for grievers to be the ones who inform others because it helps the reality of the loss become real. The nurse can offer to find a phone number or hold the griever’s hand during the conversation or just “be there” when the news is being shared. In this way the nurse can be available to provide support when the griever’s emotions engage and move toward wellness and equilibrium.

As the elder moves forward in adjusting to the loss, such as a move from home to a nursing home, the nurse can help the person reorganize the structure of life. The nurse talks with the elder about what was most valued about living at home and what habits were comforting, and finds ways to incorporate these in a new way into the new environment. If the elder does not have access to a kitchen and always had a cup of tea before bed, this can become part of the individualized plan of care.

According to the Loss Response Model, memories are reframed in order for the cycle of grieving to be completed. The grandmother who had always hosted her eldest daughter’s birthday party can still do that even if she is now a resident in a long-term care facility. When the nurse has the information about this important ritual, she or he can help the person reserve a private space, send out invitations, and have the birthday party as always, just reframed in that it is catered by the facility in the elder’s new “home.”

Countercoping

Avery Weisman (1979) described the work of health care professionals related to grief as “countercoping.” Although he was speaking of working with people with cancer, it is equally applicable to working with people who are grieving for any loss and for families coping with the pending or past loss. “Countercoping is like counterpoint in music, which blends melodies together into a basic harmony. The patient copes; the therapist [nurse] countercopes; together they work out a better fit” (Weisman, 1979, p. 109). Weisman suggests four very specific types of interventions or countercoping strategies: (1) clarification and control, (2) collaboration, (3) directed relief, and (4) cooling off.

Clarification and control.

The nurse helps griever(s) cope with loss by helping them confront it by getting or receiving information, considering alternatives, and finding a way to make the grief manageable. The nurse helps persons resume control by encouraging them to avoid acting on impulse. It may be necessary to say, “No, this is probably not a good time to make any major decisions.”

Collaboration.

The nurse collaborates by encouraging grievers to share stories with others and repeat the stories as often as is necessary as they “talk it out.” The nurse as a collaborator is more directive than usual; it may be acceptable to say, “Yes—this is a good time to talk.”

Directed relief.

Some temporary directed relief may be necessary, especially during acute grief. Catharsis may be helpful. In many instances it is the nurse who encourages the griever to cry or otherwise express feelings such as hurt or anger which is culturally acceptable to them. The nurse may have to say something like, “Expressing your feelings might help.” Activity may also be recommended as a natural extension of feelings. Intense physical activity gives one emotional relief. In some cultures, people may tear their clothes or cut their hair. Today, there are numerous ways of acting out feelings—from throwing things, to taking a walk, to busying oneself with tasks, to expressing feelings through creative works.

Cooling off.

From time to time grievers might need to be encouraged to temporarily avoid active mourning through diversions that worked in the past during times of stress, especially when things have to be done or decisions have to be made. The nurse may need to suggest new tactics that may prove helpful. Although there is considerable cultural variation, cooling off also means encouraging the person to modulate emotional extremes at times and to think about ways to make sense of the loss, to build a new sense of self-esteem after the loss, and help reestablish life patterns.

In all interventions related to grief, the nurse must have skills in therapeutic communication. Active listening is greatly preferable to giving advice. When listening, the nurse soon discovers that it is often not the actual loss that is of utmost concern, but rather the fear associated with the loss. If the nurse listens carefully to both the stated and the implied, what will be heard may be expressions such as the following: “How will I go on?” “What will I do now?” “What will become of me?” “What will happen to my loved ones, pets, etc.?” “I don’t know what to do.” “How could he (she) do this to me?” Because the nurse knows there will be resolution of some kind, such comments may seem exaggerated or melodramatic, but to the one who is acutely grieving there seems to be no resolution. The person cannot yet look ahead and know that the despair and other feelings will lessen. Like good copers, good gerontological nurses must be flexible, practical, resourceful, and abundantly optimistic.

Dying, death, and palliative care

Many people have said that death is not the problem, it is the dying that takes the work. This is true for all involved: the person who is dying, the loved ones, and the professional caregivers, such as nurses and, in long-term care facilities, nursing assistants (Anderson & Gaugler, 2006-2007).

Dying is both a challenging life experience and a private one. How one deals with dying is a reflection of one’s culture and the way the person has handled earlier losses and stressors. Most people probably do die as they have lived. Although not all older adults have had fulfilling lives or have a sense of completion, transcendence, or self-actualization, their deaths at the age or after that of their parents are considered normative. If the dying process is particularly long or the death occurs after a painful illness, we may rationalize it or view it as a relief, at least in part. Death at a younger age or as the result of trauma or catastrophe is viewed as tragic and sometimes incomprehensible. After the Indonesian tsunami or the blowing up of the World Trade Centers in New York City on 9/11 no one rationalized the deaths of the older victims as a relief; all deaths were considered an unacceptable loss of human potential.

Conceptual models

As models have been proposed to explain the grieving process, so have they been proposed for the process of dying. One of the most well known has been that of Dr. Elizabeth Kübler-Ross. In her book On Death and Dying (1969) she reported on her observations of inpatients on the psychiatric ward where she did her psychiatry residency. She proposed the stages of dying as denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Nurses and many others have tried to help the dying work through denial to achieve acceptance before their deaths. However, we have come to realize that the “stages” are actually types of emotional reactions to dying that people experience rather than a stepwise progression. An alternative model that has been very useful to nursing practice is presented next.

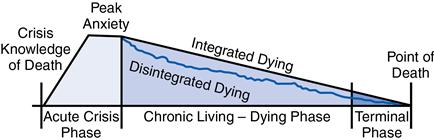

The living-dying interval

As proposed by the theories of aging (Chapter 5) we begin dying early at the time of birth; yet in realistic terms dying begins at a moment called the “crisis knowledge of death” (Pattison, 1977, p. 44) and ends at the moment of physiological death. Pattison (1977) calls the time between these two points the living-dying interval, made up of the acute, chronic, and terminal phases (Figure 25-2). The chronological time of the living-dying interval is accordion-like because of remissions and exacerbations in the terminal diagnosis; it may last days, weeks, months, or years. The manner in which one faces dying is an expression of personality, circumstances, illness, and culture.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree