Care of Patients with Disorders of the Brain

Objectives

2. Explain why seizure may be a consequence of a stroke, tumor, or infection in the brain.

3. Compare the subjective and objective findings of thrombotic stroke and intracerebral bleed.

6. Describe subjective and objective findings indicative of a brain tumor.

7. Explain the pathophysiology behind the symptoms of a brain tumor.

8. Diagram the mechanism by which infection in the brain may cause increased intracranial pressure.

9. Recall the signs of increasing intracranial pressure from early to late signs.

10. Compare and contrast symptoms of meningitis and encephalitis.

11. Explain the assessment data that differentiate migraine headaches from cluster headaches.

12. Compare the signs, symptoms, and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia and Bell’s palsy.

2. Perform neurologic checks on a patient who is admitted with a suspected CVA.

3. Assist with the care of a patient who has had intracranial surgery.

4. Devise a teaching plan for the patient who has suffered a CVA and has right-sided hemiplegia.

Key Terms

agnosia (ăg-NŌ-zhă, p. 532)

aneurysm (ĂN-ūr-ĭ-zĭm, p. 528)

aphasia (ă-FĀ-zhă, p. 532)

apraxia (ă-PRĂK-sē-ă, p. 532)

ataxia (ă-TĂK-sē-ă, p. 532)

aura (ĂW-ră, p. 524)

automatisms (ăw-TŌM-ă-tĭsmz, p. 524)

dysarthria (dĭs-ĂHR-thrē-ă, p. 532)

dysphasia (dĭs-FĀ-zhă, p. 532)

embolus (ĔM-bō-lŭs, p. 528)

epilepsy (Ĕ-pĭ-lĕp-sē, p. 524)

homonymous hemianopsia (hō-MŎN-ĭ-mŭs hĕ-mē-ă-NŎP-sē-ă, p. 532)

hydrocephalus (hī-drō-SĔF-ă-lăs, p. 542)

infarct (ĭn-făhrkt, p. 528)

nuchal rigidity (NŪ-kăl, p. 542)

postictal (PŌST-ĭk-tĕl, p. 524)

ptosis (TŌ-sĭs, p. 546)

scotoma (skō-TŌ-mă, p. 545)

status epilepticus (STĂ-tŭs ĕp-ĭ-LĔP-tĭ-kŭs, p. 524)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Seizure Disorders and Epilepsy

Etiology

Seizures can be symptomatic of a large number of disorders. Brain injury from a stroke, pressure from a brain tumor, infectious diseases with high fever, end-stage renal disease with uremia, toxicity (such as that occurring in eclampsia during pregnancy or in drug poisoning), epilepsy, and tetanus are but a few examples of seizure-producing disorders. Seizures also can occur any time the brain is deprived of oxygen.

Seizures may be symptoms of an underlying illness. Metabolic disturbances such as acidosis, electrolyte imbalances, hypoglycemia, hypoxia, and water intoxication may cause seizures. Alcohol or barbiturate withdrawal can cause seizures. In children, a high temperature is a frequent cause of seizures. There are at least 40 types of seizure disorders linked to genetic defects. Epilepsy is present when correcting the metabolic problem does not stop the seizures. Epilepsy affects 4 to 8 in 1000 people in the United States (Ko & Sahai-Srivastava, 2009). Incidence increases in those 60 to 80 years of age.

Pathophysiology

Epilepsy is a chronic disturbance of the nervous system characterized by various types of recurrent seizures that are the result of abnormal electrical activity of the brain. Epilepsy is characterized by spontaneous recurring seizures. It is thought that in epilepsy a group of abnormal neurons fire spontaneously. Some unknown stimulus causes the cell membranes to depolarize. The depolarization of the neurons causes abnormal sensory or motor activity and may cause unconsciousness. The neurons involved have a low threshold for excitation. The excitation spreads to surrounding cells, spreading the activity to a small area or throughout the brain.  Seizures are classified as partial or generalized. Each seizure lasts a few seconds or a few minutes. The abnormal electrical activity generated can be captured by an electroencephalogram (EEG).

Seizures are classified as partial or generalized. Each seizure lasts a few seconds or a few minutes. The abnormal electrical activity generated can be captured by an electroencephalogram (EEG).

Signs and Symptoms

Partial Seizures

Partial seizures are further divided into three subgroups: simple partial seizures, in which consciousness is not impaired but there are other motor, sensory, autonomic, or psychological symptoms; complex partial seizures, in which there is some impairment of consciousness with or without automatisms (repetitive, automatic actions such as lip smacking); and partial seizures that become generalized as the seizure continues.

Partial seizures also are called simple or focal seizures and result from an abnormal localized cortical discharge. Partial seizures with complex symptomatology may also be called temporal lobe seizures because they usually originate in the temporal lobe of the brain. Partial seizures can be unilateral, with involvement on only one side of the brain and activity only on one side of the body.

Generalized Seizures

Generalized seizures are bilaterally symmetrical (affecting both sides of the body equally) and do not have a local onset; that is, they do not typically begin in one part of the body. Generalized seizures have symptoms or activity that is bilaterally symmetrical and include absence, myoclonic, clonic, tonic, tonic-clonic, and atonic seizures and infantile spasms (usually caused by increased temperature).

Generalized seizures are characterized by bilateral synchronous electrical discharges in the brain. The whole brain is affected and there is no warning or aura (preceding sensation). The patient usually quickly loses consciousness lasting for a few seconds up to several minutes.

The manifestations of epilepsy depend on the area of the brain where the abnormal firing occurs. Absence or petit mal seizures last only a few seconds. The onset is sudden, with no aura or warning and no postictal symptoms. Seizures of this type tend to affect children between 5 and 12 years of age and disappear during puberty. There usually is a twitching about the eyes and mouth. The person remains standing or sitting and appears to have had no more than a lapse of attention or a moment of absentmindedness.

With tonic convulsions, there is continued contraction of all muscles and the body becomes rigid. Grand mal or tonic-clonic seizures usually begin with bilateral jerks of the extremities or focal seizure activity. There is loss of consciousness with both tonic and clonic convulsions. The patient may be incontinent during the attack, and there is danger of biting the tongue. In the postictal (after a seizure) phase, the person is confused and drowsy.

Atonic or akinetic seizures are characterized by loss of body muscle tone that results in nodding of the head, weakness of the knees, or total collapse and falling (“drop attacks”). The person usually remains conscious during the attack.

The third major group, unclassified seizures, simply means that not enough data have been obtained to determine which type of seizure the patient is experiencing.

The fourth designation, status epilepticus, indicates prolonged partial or generalized seizure without recovery between attacks. Status epilepticus is a grave condition in which there is a rapid, unrelenting series of convulsive seizures without intervening periods of consciousness, and an absence of respiration. Irreversible brain damage can occur if the seizures are not controlled.

In classifying epileptic seizures on the basis of origin, seizures are grouped as either idiopathic or symptomatic. Idiopathic epilepsy has no known cause. Symptomatic epilepsy has a known physical cause (e.g., brain tumor, injury to the head at birth, a wound or blow to the head, toxicity, or an endocrine disorder).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of epilepsy is based on the history and the actual signs and symptoms observed during a seizure. A thorough physical examination and tests for underlying disease are ordered based on the history and physical findings. Confirmation of the diagnosis is by EEG and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These tests help locate the site, or locus, and possibly the cause of the seizures. Electrolyte levels are determined as imbalances may predispose to a seizure.

Treatment

When the cause of seizures is known, as in cases of high fever or drug toxicity, medical treatment is aimed at controlling or eliminating whatever is responsible for the seizures. For recurrent seizures, as in epilepsy, the condition usually is managed with anticonvulsant drug therapy. An implanted vagus nerve stimulator is proving helpful for generalized epilepsy for many patients with uncontrolled seizures.

The major antiepileptic drugs are presented in Box 24-1. Patient education is extremely important, because the patient will need to report any untoward effects to the physician or nurse clinician so the dosage can be adjusted or the drug changed. All anticonvulsant drugs cause some central nervous system (CNS) depression with grogginess, dizziness, fatigue, and cognitive changes.

A ketogenic diet is beneficial in younger patients with refractory (difficult to control) generalized seizures. A ketogenic diet provides sufficient calories from fats and proteins, but produces a ketotic (acidotic) state that seems to prevent seizure activity.

Biofeedback techniques are geared toward teaching the patient to maintain a certain brainwave frequency that is not susceptible to seizure activity.

Treatment of status epilepticus depends on its cause. Many times patients who are known to have epilepsy arrive in the emergency department with status epilepticus because, for one reason or another, they stopped taking the medication that controls their seizures. Treatment in this instance would involve administering lorazepam, phenytoin, and/or phenobarbital in a dose sufficiently high to stop the seizures (Cavazos, 2009).  Care is focused on supporting vital signs and preventing injury. Intubation may be required for respiratory support. If seizures will not stop, an anesthetic agent may be required. Rectal diazepam has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in a system called Diastat AcuDial. It can be used at home by nonprofessional caregivers, and clinical studies have shown that the system resolved seizures in 85% of patients (Epilepsy Action, 2010).

Care is focused on supporting vital signs and preventing injury. Intubation may be required for respiratory support. If seizures will not stop, an anesthetic agent may be required. Rectal diazepam has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in a system called Diastat AcuDial. It can be used at home by nonprofessional caregivers, and clinical studies have shown that the system resolved seizures in 85% of patients (Epilepsy Action, 2010).

Surgical Treatment

Surgical procedures involve removing the epileptic focus or preventing the spread of epileptic activity by sectioning the corpus callosum. A temporal lobe resection may eliminate seizures in more than 70% of patients with temporal lobe seizures. For patients with extensive damage in one side of the brain that causes intractable seizures, a hemispherectomy may be performed. Surgeries are not without danger and are reserved for those patients whose seizures cannot be managed by medical treatment and in whom the focus of the seizures is accessible.

For intractable partial seizures, a NeuroCybernetic Prosthesis (vagal nerve stimulator) can be implanted in the chest cavity with a wire tunneled to stimulate the vagus nerve. The device acts like a pacemaker and provides a tiny electric jolt every 5 minutes that stimulates the brain to interrupt seizures (Carroll & Berbadis, 2009).

Uncontrolled seizures secondary to hypoglycemia (as in improperly controlled diabetes mellitus) can be relieved by IV administration of 50% dextrose. If the unrelenting seizures are caused by chronic alcoholism or withdrawal, treatment consists of IV administration of thiamine.

Nursing Management

Assessment (Data Collection)

Patients with a known seizure problem usually are treated on an outpatient basis, but may be encountered in the hospital or long-term care facility. Assess the patient carefully to provide optimal safety and care. Significant history information includes the kind of seizures they experience, whether they have any sensation just before the appearance of clinically observable signs, what medications they are taking, and what measures are known to be helpful either to prevent a seizure or to assist while they are having a seizure and afterward. Assessment should include any factors that could have triggered the seizure (e.g., hyperventilation, bright lights [photosensitivity], alcohol and other drugs, fluid and electrolyte imbalances, lack of sleep, and emotional stress).

When caring for a patient who is likely to experience a seizure during an acute illness, periodically observe the patient for tremors, unexplained sensory or motor changes, mental changes that indicate confusion or disorientation, and restless or agitated behavior. In many cases, a change in the neurologic status of a patient can signal the possibility that a seizure might occur.

Nursing Diagnosis, Planning, and Implementation

The main nursing diagnosis for the patient who experiences seizures is Risk for injury related to seizure activity. Expected outcomes are written for the individual patient and the type of seizure disorder, possible triggers, and manifestations.

Nursing care of patients with epileptic seizures is concerned with immediate care during and after a seizure and long-term management and control of seizures and their psychosocial implications. Witnessing a seizure for the first time can be a frightening experience. The nurse’s first responsibility is to stay calm, remain with the patient, and call for assistance.

The environment of a patient at risk for seizure should be made as safe as possible. If the patient is very likely to have seizures, the side rails and headboard of the bed are padded. Never try to pry open the patient’s mouth or insert something into it once the jaw is clamping down, as teeth may be broken and the airway may become obstructed.

If a seizure comes on without warning and the patient drops to the ground, leave her wherever she is lying. If she is on a hard surface, her head should be protected from injury by placing a rolled blanket or coat under it. The head should be turned to the side, if possible, to prevent aspiration of secretions. Do not attempt to restrain the patient’s movements or to move her to a bed or chair during the seizure. If supplemental oxygen is near, it should be administered, if possible. Call for help and provide privacy, if possible. When the seizure is over, turn the patient to the side, and suction the airway if needed. Check oxygen saturation with a pulse oximeter. Check the glucose level, if possible, and assess for injuries. Stay with the patient until she is completely conscious. When consciousness is regained, reorient and reassure her. The patient should be allowed to rest or sleep after the seizure. Thoroughly document the event in the medical record with time, duration of the seizure, and observations of the seizure activity and any aura that occurred before its start.

The long-term management of epileptic seizures is primarily focused on providing the patient with the information and support she needs to care for herself and to avoid recurring and debilitating seizures. Psychosocial support is necessary to encourage the patient to talk about her fears and concerns. Lifestyle changes will have to be made if she is not permitted to drive. Most states allow resumption of driving when a patient has been seizure free for 1 year. A referral to the local epilepsy society for connection with a support group can be very helpful for both the patient and her family.

Most individuals who suffer from epileptic seizures are perfectly normal between seizures; they are not mentally retarded and are quite capable of becoming contributing members of society if only they are given the chance to prove their worth.

Patient Education

Self-care for the epileptic patient requires that she understand the nature of her disorder, the purpose of her prescribed medications, their side effects, and the signs of toxicity that should be reported to the physician. The patient must understand the necessity for compliance with the prescribed regimen to avoid recurrent seizures. She will need assistance in developing coping mechanisms to deal with the psychosocial impact of having epilepsy.

Evaluation

Evaluation is based on whether the expected outcomes are being achieved. This will include whether the patient is seizure free, or whether the number of seizures has decreased. Patient compliance with the medication regimen and avoidance of triggers for seizure activity is evaluated as well. Patient teaching may need to be reinforced. If progress toward the achievement of outcomes is not occurring, the plan must be revised.

Transient Ischemic Attack

Between 200,000 and 500,000 Americans experience what are called transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) each year. TIAs are caused by a brief interruption in blood flow. Narrowed arteries and vascular occlusion, perhaps by small emboli or vasospasm, cause the interruption. Recreational drugs that constrict vessels are another cause of TIAs. TIAs are warnings that a more serious neurologic event may occur; 11% of patients who experience a TIA have a stroke within 90 days. During the TIA, the person may feel a sudden weakness or numbness on one side of the body, slurring of speech or inability to talk, visual disturbances such as blindness or double vision, confusion, diminished coordination or ability to balance, and a headache. Symptoms are similar to those of a stroke. These symptoms generally last no more than an hour and completely resolve without residual deficits (Goldstein, 2011). It is very important that the person be evaluated by medical personnel, as the same symptoms may indicate a stroke that will not resolve without treatment.

A thorough history of the event is essential: how it began, the symptoms experienced, and how long it lasted. If carotid obstruction is suspected, carotid duplex ultrasound studies are done to determine if obstruction in the carotid arteries is preventing normal blood flow from reaching the brain. Multiple tests may be performed if carotid occlusion is ruled out, including blood tests, MRI, and EEG. If there is near-total occlusion of the carotid artery, either an angioplasty procedure with stent implantation or a carotid endarterectomy is considered. If occlusion from plaque obstruction is less than 60%, medical treatment with diet and lifestyle modification and medication to prevent platelet aggregation (i.e., aspirin, clopidogrel [Plavix], dipyridamole [Persantine]) is prescribed.

Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke, Brain Attack)

Etiology

More than 795,000 first and repeat strokes occur in the United States each year. Stroke is the leading cause of disability and the third leading cause of death (Stroke Center, 2010). The incidence is about 19% higher in males than in females. About 25% of cases occur in people younger than age 65 (American Heart Association, 2009). An increase in public education about the risk factors for and signs of stroke could result in lessened disability and death from stroke.

Control of high blood pressure, quitting cigarette smoking, decreasing intake of cholesterol and controlling blood lipids, maintaining a normal blood sugar level, avoiding excessive alcohol intake, getting sufficient exercise, avoiding obesity, and living a lifestyle that helps prevent heart disease can help reduce the risk of stroke. Atherosclerosis is a major cause of stroke, as it can predispose to thrombus formation in the brain vessels or plaque in other arteries that can break off and become emboli.

Pathophysiology

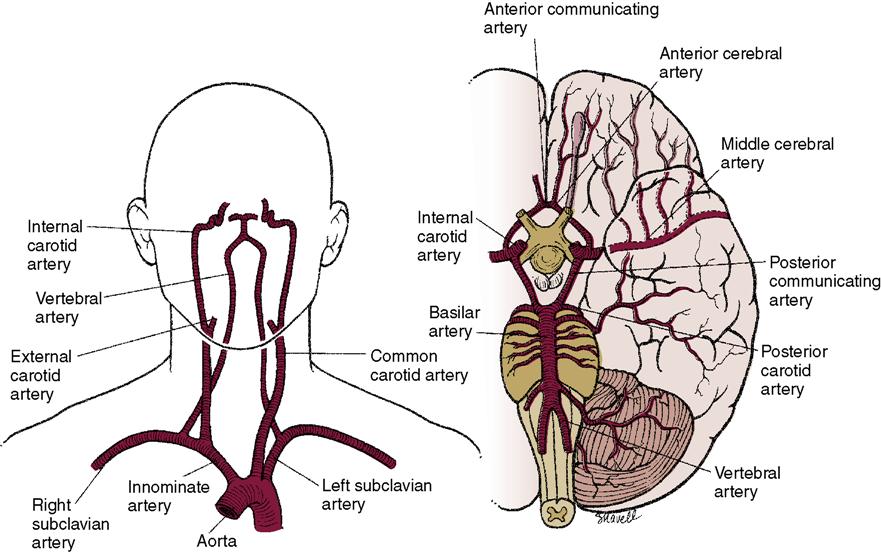

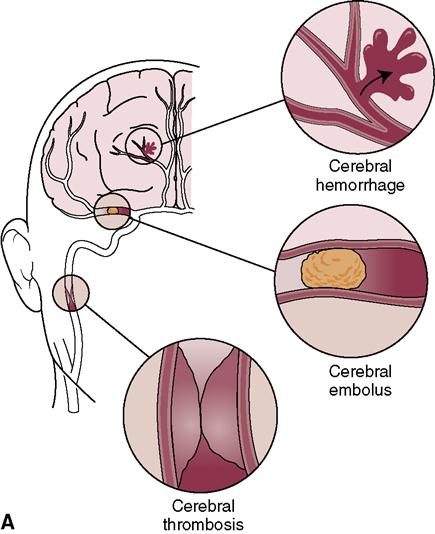

A cerebrovascular accident (CVA) is the result of an interruption of blood flow to a specific area of the brain (i.e., cerebral ischemia). Ischemia of cells directly causes cellular necrosis (death) and infarct (area of tissue that has become necrotic from lack of blood supply) (Figure 24-1). Ischemia can be caused by:

• Cerebral thrombosis (formation of a blood clot in a cerebral artery)

• An embolus (a traveling clot, fat, bacteria, or tissue debris that lodges in a vessel, occluding it)

The carotid arteries supply a major portion of the blood that goes to the brain (Figure 24-2). If plaque forms in these arteries as a result of atherosclerosis, the person is at risk for a stroke as blood supply to the brain is diminished or stopped. Less common causes of stroke are arterial spasms, compression of cerebral vessels by a tumor, local edema, rupture of a cerebral aneurysm, or another disorder.

Cerebral Aneurysm and Arteriovenous Malformation

Structures that can cause an intracerebral hemorrhage are an aneurysm and an arteriovenous malformation. An aneurysm is an abnormal ballooning of an artery wall (Figure 24-3). It may be congenital or caused by a weakening of the artery wall from chronic hypertension. Rupture of a brain aneurysm causes bleeding into the subarachnoid space or into the ventricles. An arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a congenital abnormality and is a tangled mass of malformed, thin-walled, dilated vessels that form an abnormal communication between the arterial and venous systems. An AVM can leak, causing an intracerebral hemorrhage. Vasospasm often occurs after intracerebral bleeding, leading to further ischemia of the brain tissue and more neurologic impairment. Resultant deficits are the same as for other kinds of strokes.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage, which refers to bleeding in the brain below the arachnoid, often causes rapid onset of neurologic deficit and loss of consciousness. A leaking cerebral aneurysm may cause a severe headache. However, sometimes bleeding is slower, producing a more gradual progression of headache, neck stiffness, and other neurologic signs, such as blurred vision.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage, which refers to bleeding in the brain below the arachnoid, often causes rapid onset of neurologic deficit and loss of consciousness. A leaking cerebral aneurysm may cause a severe headache. However, sometimes bleeding is slower, producing a more gradual progression of headache, neck stiffness, and other neurologic signs, such as blurred vision.

Stroke Prevention

Many strokes can be prevented by either surgical procedures or by medical management of diseases that predispose a person to a CVA. An angioplasty with stent placement is an option for opening occluded carotid arteries. Care for patients undergoing vascular surgery is presented in Chapter 21.

Aneurysms and AVMs can sometimes be surgically corrected, if found before rupture. Medical preventive measures are aimed at eliminating or managing some of the conditions that predispose a person to stroke. Control of hypertension and the effective treatment of inflammatory heart disease, congenital heart defects, cardiac dysrhythmias, and atherosclerosis have significantly reduced the incidence of stroke. Teaching people to seek assistance immediately when signs of stroke occur may allow medical intervention that will decrease permanent neurologic deficit.

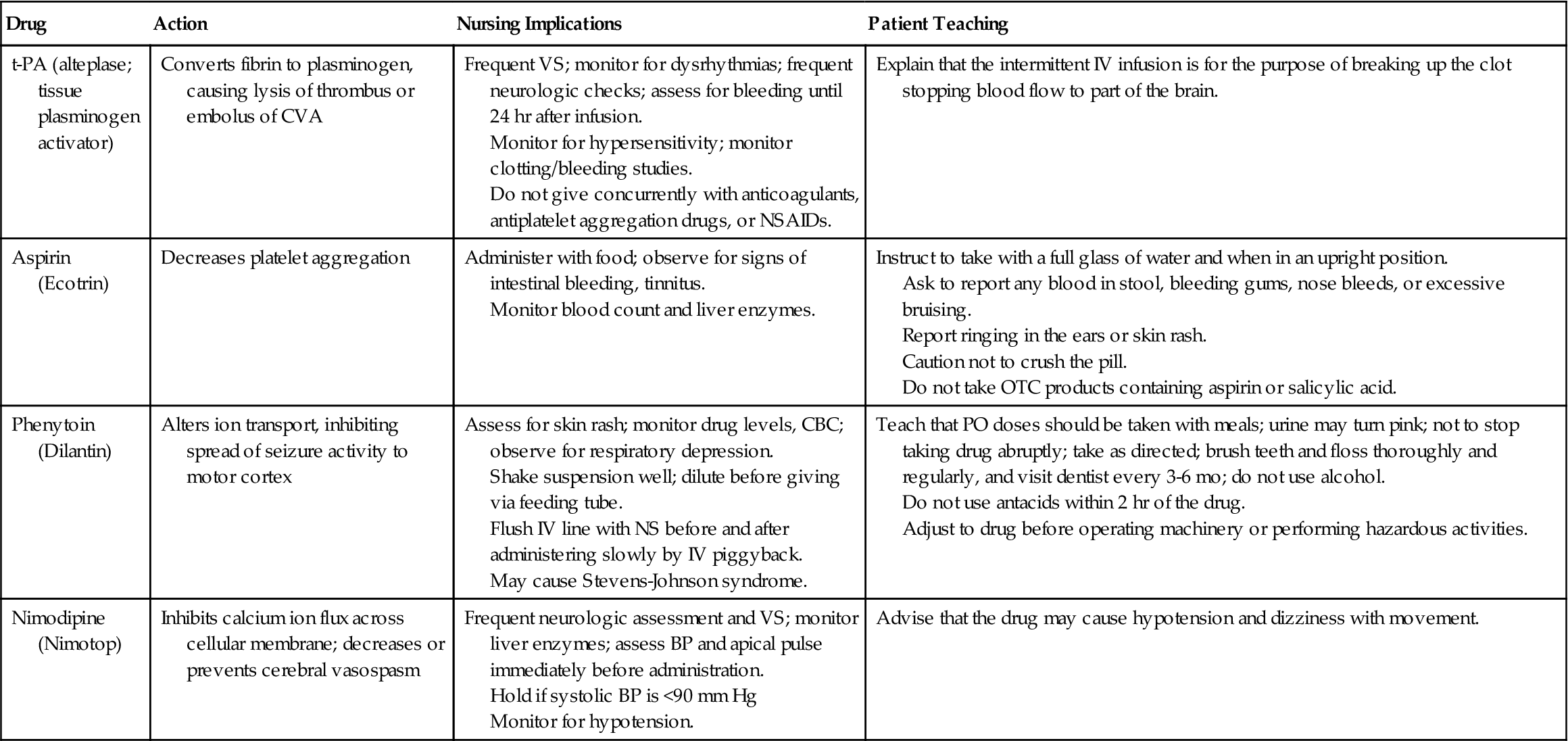

Aspirin or another drug to reduce platelet aggregation and decrease the chance of thrombosis often is prescribed to prevent the recurrence of stroke from thrombosis (Table 24-1). A combination of two inflammatory marker blood tests is showing promise in predicting which middle-aged people are at risk of a stroke. Researchers reported that C-reactive protein and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (LP PLA2) were higher in those who later had an ischemic stroke than in those who did not have a stroke (Wright et al., 2009).

Table 24-1

Table 24-1

Medications Commonly Used for Patients after a CVA

| Drug | Action | Nursing Implications | Patient Teaching |

| t-PA (alteplase; tissue plasminogen activator) | Converts fibrin to plasminogen, causing lysis of thrombus or embolus of CVA | Frequent VS; monitor for dysrhythmias; frequent neurologic checks; assess for bleeding until 24 hr after infusion. Monitor for hypersensitivity; monitor clotting/bleeding studies. Do not give concurrently with anticoagulants, antiplatelet aggregation drugs, or NSAIDs. | Explain that the intermittent IV infusion is for the purpose of breaking up the clot stopping blood flow to part of the brain. |

| Aspirin (Ecotrin) | Decreases platelet aggregation | Administer with food; observe for signs of intestinal bleeding, tinnitus. Monitor blood count and liver enzymes. | Instruct to take with a full glass of water and when in an upright position. Ask to report any blood in stool, bleeding gums, nose bleeds, or excessive bruising. Report ringing in the ears or skin rash. Caution not to crush the pill. Do not take OTC products containing aspirin or salicylic acid. |

| Phenytoin (Dilantin) | Alters ion transport, inhibiting spread of seizure activity to motor cortex | Assess for skin rash; monitor drug levels, CBC; observe for respiratory depression. Shake suspension well; dilute before giving via feeding tube. Flush IV line with NS before and after administering slowly by IV piggyback. May cause Stevens-Johnson syndrome. | Teach that PO doses should be taken with meals; urine may turn pink; not to stop taking drug abruptly; take as directed; brush teeth and floss thoroughly and regularly, and visit dentist every 3-6 mo; do not use alcohol. Do not use antacids within 2 hr of the drug. Adjust to drug before operating machinery or performing hazardous activities. |

| Nimodipine (Nimotop) | Inhibits calcium ion flux across cellular membrane; decreases or prevents cerebral vasospasm | Frequent neurologic assessment and VS; monitor liver enzymes; assess BP and apical pulse immediately before administration. Hold if systolic BP is <90 mm Hg Monitor for hypotension. | Advise that the drug may cause hypotension and dizziness with movement. |

BP, blood pressure; CBC, complete blood count; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; IV, intravenous; NS, normal saline; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OTC, over the counter; PO, oral; t-PA, tissue plasminogen activator; VS, vital signs.

See Chapter 21 for information on warfarin (Coumadin).

Cerebral ischemia caused by thrombosis causes signs that progress slowly. Thrombosis develops in an area of the vessel where there is atherosclerotic plaque. Lodging of an embolus in a major cerebral vessel causes sudden neurologic deficit. Emboli most often are the result of heart disease and resultant atrial fibrillation, a cardiac dysrhythmia.

Signs and Symptoms

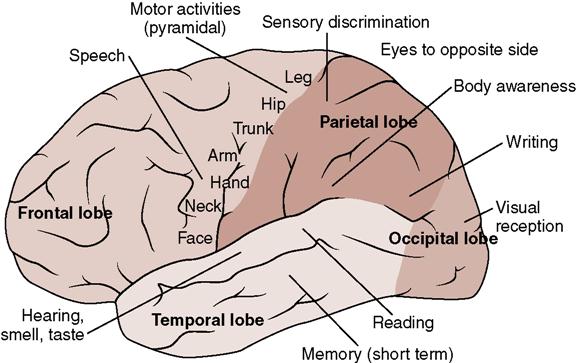

The neurologic effects of stroke can range from mild motor disturbances to profound coma. Figure 24-4 shows selected control zones of the brain and motor and sensory functions likely to be affected by a stroke. Signs and symptoms will depend on the type of event that has caused the stroke and the location of the clot or bleed. There may be weakness (hemiparesis) or paralysis (hemiplegia),difficulty or inability to speak or understand (dysarthria or aphasia), difficulty with vision, loss of balance or poor coordination (ataxia), decreased level of consciousness, and confusion. Incontinence may occur. Bleeding into the brain or edema around necrotic tissue causes intracranial pressure (ICP) to increase (see Chapter 23 regarding increasing ICP).

Motor function deficits affect mobility, respiratory function, swallowing, speech, gag reflex, and self-care abilities. Because the pyramidal pathways cross at the level of the medulla, injury to brain cells in the right hemisphere affects the left side of the body and damage to cells in the left hemisphere affects the right side of the body. There may be hemiplegia or hemiparesis. Muscle tone is usually flaccid at first, and then there may be spasticity and hyperreflexia. Keeping the body in good alignment to prevent contractures is very important.

Language disorders involve expression and comprehension of both written and spoken words. Aphasia or dysphasia (minimal speech activity) or a mixed type of aphasia may occur (see Chapter 22). Many stroke patients experience dysarthria (difficulty in speaking) due to lack of muscular control of the tongue. A speech therapist works with the patient to improve speech capability. There are computer software programs for rehabilitation of the aphasic patient that have been beneficial to many.

The frustration of trying to perform a function that has always been easy before the stroke may cause the patient to cry. Alternatively, the patient may display an angry emotional outburst, and sometimes foul language.

Memory and judgment may be affected by the stroke. The ability to learn may be affected, which makes relearning activities to promote independence a slow process. A great deal of patience and encouragement is needed from the staff working with the patient.

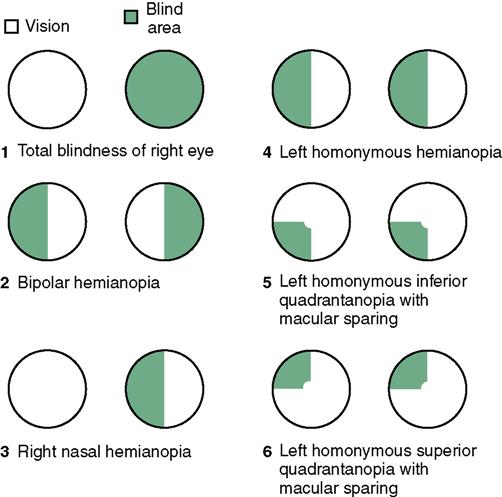

Spatial-perceptual deficits may cause the patient to totally neglect input from the affected side of the body (unilateral neglect). She must be taught to attend to the body parts on that side of the body in order to protect them from injury. Homonymous hemianopsia (blindness in part of the visual field of both eyes) adds to the spatial-perceptual problems by making it difficult to judge distances (Figure 24-5). The patient is taught ways to deal with the problems of the particular type of visual defect developed. Agnosia (inability to recognize an object by sight, touch, or hearing) makes it difficult to do ordinary tasks. Apraxia (the inability to carry out learned sequential movements on command) adds to the difficulty in regaining independence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree