Rural and Migrant Health

Patricia L. Thomas and Patti J. Shoe*

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Compare and contrast characteristics of rural and urban communities.

3. Discuss the impact of structural and personal barriers on the health of rural aggregates.

4. Identify factors that place farmers and migrant workers at risk for illness and accidents.

5. Discuss the importance of the informal care network to rural health and social services.

6. Describe the characteristics of rural community health nursing practice.

Key terms

disparities

frontier

metropolitan

migrant farmworkers

pesticide

rural

seasonal farmworkers

urban

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

Rural United States

There are many different versions of rural America, in that each rural area is unique in some respects but shares certain features with other rural regions. Geographic, demographic, environmental, economic, and social factors all influence health, access to health care, and quality of health care. When aggregated, these characteristics may be contrasted with those of urban populations. In this section, we present a “snapshot” of rural population and health characteristics that contribute to challenging health disparities for many of the people living in the most rural areas of America.

Although the urban growth rate has been steadily climbing since 1890, with numbers of urban dwellers surpassing those in rural areas around 1920, the number of rural residents is the highest in the country’s history (U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2008). The number and size of rural counties are highest in the South (35%), followed by the Midwest and West (23%), and Northeast (19%) (USDA, 2007). Current census estimates are that 18% of the nation’s children under age 18 years live in rural areas (USDA, 2005), as do 15% of the nation’s elderly, and more than 50% of the nation’s poor (USDA, 2007).

The economic base of rural America is changing rapidly. Whereas rural residents have long been thought to be family farmers and ranchers, today rural America is a diverse and important marketplace to marketers of consumer products, and demographers and economists consider trends in farm and farm-related employment much more broadly. They characterize agriculture as a “food and fiber system” that encompasses all aspects of agriculture, from core materials sectors (farm, food processing, textiles, and other manufacturing) to wholesale and retail trade and the food service sector (Edmondson, 2004). Despite the shrinking number of family farms and full-time farmers, agriculture continues to be an important part of the rural and U.S. economy.

Poverty, a key health determinant, continues to be greater in rural America than in urban areas. Whereas the metropolitan population had a poverty rate of 11% in 2002, the rural population had a poverty rate of 14%. This overall gap may not seem large, but when the degree of rurality or the poverty rate for particular subpopulations (e.g., minorities, children under 18 years of age, or the elderly) is examined, the gap increases greatly. For example, the poverty rate for non-Hispanic blacks in nonmetropolitan areas in 2002 was 33%, compared with a rate of 23% for the same group in metropolitan areas. The poverty rate for people in the rural South was 18%, versus 13% for Southerners living in and around metropolitan areas (USDA, 2005).

Not only is the economic base shifting, the age composition is as well. Many rural areas are growing, especially in the West and South, and many rural counties, especially in the Great Plains states, are losing population because of a decline in agricultural and manufacturing jobs. Younger people are leaving rural areas for jobs in urban centers, so that those who remain behind are increasingly older and isolated and have diminished access to health care (Whitener and McGranahan, 2003). Recent demographic changes in rural areas have also included an influx of retirees and others from urban areas, who are able to live in rural areas and conduct business through telecommunication and travel (Malecki, 2003). Recent demographic data indicate that rural persons aged 60 years and older comprise 20% of the population of nonmetropolitan areas, in contrast to 15% of the population of urban areas (Rogers, 2002). Of the nation’s rural elderly, the largest clusters live in the South (45%) and the Midwest (31%) (Rogers, 2002). The trends of “aging-in-place, out-migration of young adults, and immigration of older persons from metro areas” (Rogers, 2002, p. 2) present challenges to already stressed communities that must provide adequate health care, housing, transportation, and other human services.

The rural population is also becoming more ethnically diverse. Generations ago, many families began farming when they came to the United States as European immigrants. In the 1990s, new immigrants began buying and operating their own small family farms, and others found employment in rural agriculture and manufacturing. Today, nearly one half of rural Hispanics live outside the Southwest, and “high-growth Hispanic counties” are mostly in the South and Midwest (Kandel and Newman, 2004). Hispanics are now the most rapidly growing demographic group in rural and small-town America.

Policies and programs developed to close the health disparities gap must take a population health view of the special circumstances of rural life. Although 75% of U.S. counties are classified as rural, they contain only 20% of the U.S. population. Members of rural populations also are more likely to be older, to be less educated, to live in poverty, to lack health insurance, and to experience a lack of available health care providers and access to health care. Only 10% of U.S. physicians practice in rural counties (Crouse, 2007), and the ratio of medical specialists to rural population size is forty per 100,000 people (compared with 134 per 100,000 in urban settings) (Berkowitz, 2004).

Rural residents more often assess their health as fair or poor and have more disability days associated with acute conditions than their urban counterparts. Rural people also tend to have more problems related to negative health behaviors (e.g., obesity and alcohol, tobacco, and drug use) that contribute to excess deaths and chronic disease and disability rates. The literature suggests, for example, that the highest death rates for children and young adults were in the most rural counties. Residents of rural areas are nearly twice as likely to die of unintentional injuries, including motor vehicle accidents, when compared with their urban counterparts (National Rural Health Association [NRHA], 2008).

Noting a prominent and persistent pattern of risky health behaviors in rural dwellers, Hartley (2004) has suggested that “rural culture” may itself be a key determinant of health in rural communities and these behaviors vary along the rural-urban continuum and within rural populations by geographic areas. These behaviors, including unintentional injury, smoking, and suicide will be discussed in more detail in the section titled Composition: Health Disparities Related to Persons.

Defining Rural Populations

Multiple definitions of rural populations have been formulated to describe the characteristics of low-population-density areas. Previous definitions have simply included either those towns with a population of less than 2500 or towns located in open country as rural. This definition has often been further differentiated into subcategories of farm and rural nonfarm. A second classification of interest used the term rural for populations with fewer than forty-five persons per square mile, and the term frontier for geographic areas with fewer than six people per square mile (Rural Health Assistance Center, 2010). Many counties of the Great Plains, Intermountain West, and Alaska are designated frontier.

The rural-urban continuum distinguishes counties by population and adjacency to metropolitan areas. Residences can range from small towns to large metropolitan areas. Statistical reporting has been in use since 1990. Census maps and statistical reports in use since the 1990s used the term Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) to differentiate nonmetropolitan and metropolitan areas. In June 2003, however, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) released a new classification scheme, developed in 2000, to better reflect trends in population distribution across the nation (OMB, 2008). The MSA designation has been replaced by county-level Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs), which make up a new classification scheme to simplify the multilevel designations in use since 1990. The new CBSA system includes two categories of counties: metropolitan areas and micropolitan areas. Counties that are neither metropolitan nor micropolitan are called “outside CBSAs,” also known as noncare areas. Within CBSAs, metropolitan areas are those counties that contain at least one urbanized area of 50,000 or more people. A micropolitan area contains a cluster of 10,000 to 50,000 persons. Because the MSA classification is used extensively for congressional policymaking and funding decisions, the change could have serious ramifications for health care financing within rural market areas.

Describing Rural Health and Populations

Rural populations differ in complex geographic, social, and economic areas. Although older, poorer, and less-educated people are usually overrepresented in rural areas, this may not apply to all rural areas or to everyone in a particular rural area.

The health profiles discussed below are shared by rural areas in general and may be contrasted with overall patterns of health, health habits, and health care in urban settings. However, the reader should note that it is difficult to interpret differences between urban and rural health. First, statistically significant differences between urban and rural health indicators may seem small when data are aggregated to “rural areas” in general. The differences tend to become larger when data are available for particular rural areas (e.g., certain counties), particular rural subgroups (e.g., minorities), or specific characteristics (e.g., percentage of uninsured children). Second, heterogeneity of race, age, economic status, regional distribution, and cultural groupings makes health data for rural populations useful only as estimates of individual health. For example, there were 37.3 million people in poverty in 2007, up from 36.5 million in 2006. The family poverty rate was 9.8%, unchanged from 2006. Furthermore, the poverty rate and the number in poverty showed no statistical change between 2006 and 2007 for the different types of families (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008b).

Infant mortality, a major health status indicator, varies greatly by geographic area, even within rural areas, and dramatizes the importance of both contextual and compositional data. For non-Hispanic whites, the rates of infant deaths per 1000 live births continued a downward trend. For black Americans, the rate of infant deaths is 2.5 times that of whites and Hispanics. In both the South and West, rural counties experienced the highest rates (24% and 30% higher than fringe areas of large metro areas) (Hoyert, Kung, and Smith, 2005). Infant mortality rates ranged from 10.32 per 1000 live births for Mississippi to 4.68 per 1000 live births for Vermont. The highest rate noted (11.42) was for the District of Columbia. Overall, the infant mortality rate declined 10% from 1995 until 2004 (7.57); however, the rate has not declined much since 2000. From 2000 until 2005, small declines were observed for all races and ethnic groups. Significant decreases were noted for infants of Central and South American (4.68), Asian or Pacific Islander (8.06), and Mexican (5.53)(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008).

Mortality for white infants in rural areas adjacent to a population center with fewer than 2500 people varied from a high of 9.85 per 1000 in the South, to 6.46 per 1000 in the West. Although the infant mortality rates have changed since 1993, infant mortality data provide insight into the heterogeneity of rural populations and show why national or even regional data may or may not reflect the status quo for a particular county or local population.

One might also consider the health disparities that exist among rural racial and ethnic minorities. Although limited because the phenomenon has only recently been studied, research findings support the conclusion that rural racial and ethnic minorities—Native Americans, Alaska Natives, Hispanics/Latinos, and African Americans—concentrated in the South and West are more disadvantaged, not only relative to rural majority members, but also relative to urban racial and ethnic minorities. The disparities include employment, income, education, health insurance, mortality, morbidity, and access to care (Probst, Moore, Glover et al., 2004).

Because population numbers are small, national rural data, limited as the data are, can only suggest the health needs of a particular area, racial or ethnic mix, or age distribution, for example. Program planners will still need to determine whether certain health or health care delivery problems apply to their specific service area. Useful data sources include state, county, and census tract level data on health and demographics available from state and federal government agencies, such as those cited in the reference section of this chapter. In planning for health-related programs, nurses can also gather community-level data from health care providers, local records, focus groups, and older residents who know the area’s history.

Rural healthy people 2020

Minority Health and Healthy People 2020

Healthy People 2020 represents the health promotion and disease prevention agenda for the nation (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], nd). Additionally, Healthy People 2020 is the United States’ contribution to the World Health Organization’s Health for All program. The framework for Healthy People 2020, developed through public consensus, builds upon the national health program established since the 1980s. It includes the broad goals of increasing quality of life and years of life, eliminating disparities in health among different population groups, and increasing access to preventive health services.

Healthy People 2020 is based on the premise that the health of the individual is almost “inseparable from the health of the larger community and that the health of every community in every State and territory determines the overall health status of the Nation” (USDHHS, 2000, p. 2). The new 10-year plan takes a bold step forward by presenting only one set of standards for the health of all racial, ethnic, income, gender, and age-groups. The new goal is to eliminate health disparities, achieve access to preventive health services, and add years of life for all groups. The challenges are great, but public health professionals and planners in every state have, or soon will have, a plan patterned on Healthy People 2020 goals to direct their efforts. A three-volume companion document to Healthy People 2010, entitled Rural Public Health 2010, has been published. These reports are designed to “better inform readers on current rural health conditions, provide insights into possible points of attack, and offer examples of models that might be employed in practice to improve health conditions” (Gamm and Hutchison, 2004, p. vi).

Rural Health Disparities: Context and Composition

To better understand the health of populations and health disparities, there is also a growing emphasis on the distinction between context, which is defined by the characteristics of places of residence, and composition, which are the collective health effects that result from a concentration of persons with certain characteristics (Probst et al., 2004). Most public health problems include elements of both context and composition, though they may be predominately one or the other (Phillips, 2004; Probst et al., 2004).

Health issues in rural areas are contextual when they derive from characteristics of place. Characteristics of place include not only natural features of geography and environment, but also the political, social, and economic institutions that build and support communities within given geographic areas. For example, limited economic opportunities, low wages, or agricultural accidents might be considered to have contextual effects on the health of populations. Problems in rural areas are compositional when they derive from individual characteristics of groups of people residing in rural settings. Examples of compositional sources of health disparities include such characteristics as age, education, income, ethnicity, and health behaviors.

Consideration of both context and composition enables us to take a more deliberate and refined approach to study, plan programs, and deliver health care services to rural populations. Although the overall health of rural Americans is worse when compared with that of urban Americans, the relationship between rurality and health is not necessarily linear. Many differences exist between rural areas in both the nature and extent of health problems. Furthermore, some rural populations share more in common with people in urban core areas than with other rural areas. Effective planning depends on understanding and documenting needs that take into account context, composition, and their interaction (Eberhardt and Pamuk, 2004). The next section presents data for problems of both contextual and compositional sources of health disparities in rural America.

Context: Health Disparities Related to Place

Regardless of their diverse demographic and geographic attributes, rural groups share certain health patterns, difficulties, and delays in obtaining health care (Ethical Insights box). Many of the contextual issues that contribute to rural health disparities are described in the introduction to the chapter (Rural United States). Many rural regions that are already sparsely populated are losing residents, which often triggers a downward spiral. People leave and services are lost; the local drugstore closes; the tax base will not support an ambulance service; most seriously ill persons must be transported long distances to get health care; jobs become scarce and younger people leave the area. Retirees may be attracted to the lower costs, but they need public health and other services provided by counties without the tax base to support them. Racial and ethnic minorities are migrating to rural areas to find employment opportunities. Structural, financial, and personal barriers to accessing health care services exist in all environments, but rural residents are unique in how they experience structural barriers.

Access to Care

In a survey of 90 national and state rural health experts, Gamm and Hutchison (2004) reported that access to health care was the number one priority identified by the majority (73%) of rural health care leaders. Access was the leading priority regardless of rural region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) and regardless of type of organization represented in the survey (state organization, public health units, centers and clinics, or rural hospitals).

Primary care

Rural areas have fewer primary care physicians than urban areas, fueling concerns about inadequate access and gaps in U.S. health care equity in many rural areas. It is estimated that rural residents have fifty-three primary care physicians (PCPs)—internists, family/general practitioners, and pediatricians—per 100,000 people compared with seventy-eight PCPs per 100,000 urban residents (Reschovsky and Staiti, 2004; Ferrer, 2007). Only 10% of physicians, 22% of nurse practitioners (NPs), 13% of psychiatric NPs, and 23% of physician assistants practice in rural areas (Hanrahan and Hartley, 2008). The pattern distribution of these practitioners has begun to resemble the distribution of physicians and other clinicians with heavy concentrations in urban areas and a growing shortage in rural and underserved areas (Ricketts, 2008). In a joint statement, the National Rural Health Association and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) said medicine has become specialized, centralized, and urban, and challenged educators to be responsive to the needs of rural underserved communities (National Rural Health Association and AAFP, 2008).

Availability of providers and health care facilities in rural areas is an important determinant of the quality of the health care delivery system and the likelihood of positive health outcomes for rural residents (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2004). A good example of the lack of specialists is the lack of mental health services available for rural dwellers of any age. The incidence of mental illness in rural areas is the same as that of urban areas, but there is far less access to mental health services in rural areas. Additionally, primary care doctors, nurses, and physician assistants, rather than mental health specialists, provide most of the mental health care in rural regions (Hanrahan and Hartley, 2008).

General health services

Population decline in rural areas, in the Great Plains and lower South for example, has resulted from an out-migration of younger people, leaving a greater concentration of older people in a dwindling population. A recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) study reported rural medical access problems in these areas, with some hospital and pharmacy closures, greater distances to travel for physician services, and limited if any choice of providers (IOM, 2005). Lack of local access to primary care and health care facilities forces rural residents to either go without or travel long distances—often over rural roads in dangerous weather conditions—to access needed care. Access to health care may become a particularly challenging and expensive proposition for the elderly who do not drive and are dependent on limited public transportation. Geography, health care costs, and lack of available services also are contextual problems that keep many rural adults and children from obtaining needed primary, secondary, and tertiary preventive services.

Health insurance

With economic decline and rising costs of health care, health insurance, or more importantly the lack of health insurance, for Americans has become a major issue for the health of the nation. An estimated 45.7 million people were without health insurance in 2007 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008a).

As with poverty and unemployment data, insurance coverage varied with race and ethnicity coverage in 2007, as did age and residence (rural or urban). For example, 10.4% of non-Hispanic whites, 19.5% of blacks, and 16.8% of Asians were uninsured for all or part of 2007; young adults were more likely to lack health insurance than older persons; and 18% of poor or near-poor children lacked coverage (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008a). Lack of insurance coverage was greatest in the South (14.2%) and West regions (12%) in 2007, and, in general, rural residents were more likely than urban residents to lack insurance (20% vs. 17%) (IOM, 2005). Two thirds of the persons living in the most rural counties are low-income families, and 30% are children (USDA, 2004b).

Health insurance coverage influences health patterns. For example, in a study by Becker, Gates, and Newsome (2004), those who had some form of health insurance much more frequently reported the influence of physicians and health education programs in self-care regimens than did those who were uninsured. In addition, obtaining health insurance can pose a financial barrier to adequate health care for rural dwellers. Research points to a “strong nexus between health insurance status, chronic illnesses and poverty” (Bolin and Gamm, 2003, p. 19). Rural people are often employed in industries characterized by seasonal work, economic uncertainty and decline, high unemployment risk, and occupational accidents and death (e.g., agriculture, mining, forestry, and fisheries). Rural industries are often small and offer low wages, thereby contributing to the increasing number of uninsured rural families. For example, self-employed farm families need to purchase private health insurance; however, in periods of hardship they often cannot afford the increasingly high premium costs (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2001). Farm families also tend to be two-parent households, so they are less likely to qualify for Medicaid, even with incomes below the federal poverty level.

Health insurance has been identified as one of the ten leading health indicators because it is generally a reliable predictor of overall health status (Cohen and Bloom, 2005). Public health professionals and health planners are most concerned with the impact of increasing numbers of uninsured children. In 1998 the overall percentage of children who were uninsured was 13.2% (Cohen and Bloom, 2005). Of the uninsured, 21% were rural children (Dunbar and Mueller, 1998). In the absence of health insurance, poverty becomes an even more powerful predictor of poor health for all age groups, and particularly for children.

In 1997, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) was enacted to improve health insurance coverage of children under 19 years of age in poor and near-poor families (see the Legislation and Programs Affecting Public Health in Rural Areas section in this chapter). In the years following passage of this program, 1997–2005, the overall percentage of children who were uninsured fell from 20% to 9%, and the number of uninsured children declined from 8.7 million (11.7%) in 2006 to 8.1 million (11.0%) in 2007 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). Gains in rural coverage were so great that rural children were actually at lower risk for being uninsured than children in urban areas. With the passage of SCHIP, some states included provisions to insure adults; however, this has not had a significant influence on rates of insured adults (Maine Rural Health Research Center, 2009). Health insurance coverage of children as well as adults varies from state to state and is influenced by employment patterns, the percentage of children in the population, state Medicaid policies, poverty levels, and racial and ethnic composition.

Composition: Health Disparities Related to Persons

To review, health problems in rural areas are compositional when they result from a concentration of persons with certain characteristics (Probst et al., 2004). Examples of compositional sources of health disparities include such characteristics as income, health behaviors, education, occupation, gender, and ethnicity. In the Rural Healthy People 2010 survey cited previously, 73% of respondents listed access to health care as the top rural health priority (Bolin and Gamm, 2003). An additional thirteen priorities listed by respondents as leading health problems are largely compositional but may also have a contextual dimension. For example, such problems as obesity, chronic pulmonary disease, and higher levels of infant mortality have a strong compositional component because their variation is related to the health behaviors and educational, socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic characteristics of the rural groups. The variation may also be contextual, because the groups have fewer educational opportunities, have low-wage jobs, lack insurance, or have genetic propensities for certain health problems.

Income and Poverty

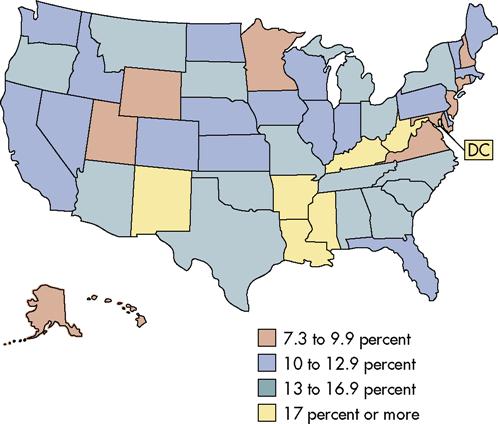

Income, education, and type of employment help determine socioeconomic status, and in the aggregate, rural dwellers have lower educational levels, higher unemployment rates, higher poverty rates, and lower income levels than urban aggregates (Probst et al., 2004). The poverty rate is one of the most important indicators of the health and well-being of all Americans, regardless of where they live (see Ethical Insights box p. 450). The USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) tracks economic trends and demographic characteristics of rural dwellers to help develop policies and services. In the most recent report, the ERS contrasted the economic growth and downward trend in poverty rates during the 1990s with those of the current decade. In the previous 10 years, rural poverty declined on average from a decade high of 17% (1993) to a low of 11% (2000). Since 2000, the rate of rural poverty has been climbing. In 2003, 14% of the general rural population lived in poverty (compared with 12% of urban dwellers) (USDHHS, 2005). Poverty rates for rural people have always been higher than those of urban dwellers (Figure 23-1). As noted earlier in this section, however, data averaged across all rural counties in the United States do not give planners and providers much information about their own counties, or even regions. On the following pages are examples of data that are available to make an analysis of local and regional conditions and characteristics.

Rural poverty: regional differences

Consistent with the idea that there are many rural Americas in rural America, rural poverty varies by rural region (Box 23-1). For example, rural counties make up 340 of 386 (88%) counties with persistent poverty rates in the United States (persistent poverty is defined as counties in which 20% of the population has been in poverty over the last 30 years). Of the 340 rural counties with persistent poverty, 280 (82%) are in the South and 60 (18%) in the West and Midwest (USDA, 2004b). Poverty is also highest in the most rural areas. In completely rural counties (i.e., not adjacent to any metropolitan counties) the poverty rate is 16.8%.

Rural poverty: racial and ethnic minorities

When poverty rates among rural dwellers are analyzed by race, ethnicity, age, and family structure, the statistics on poverty are even more dramatic than for residence or region. Racial and ethnic minorities (mainly nonwhite Hispanics, blacks, and Native Americans) constituted 17% of the rural population, according to the 2000 Census (USDA, 2004b). This segment of the rural population has grown 30% in the last decade, largely due to the dramatic increase in nonwhite Hispanics (up 70.4% from 1990 to 2000) (IOM, 2005). In 2002, according to the ERS, poverty rates among rural and racial minorities were two to three times higher than poverty rates for rural whites (11%) (USDA, ERS, 2004).

Rural poverty: family composition

Families with two or more adults are less likely to be poor, whether in rural or urban areas, because they are more likely to have multiple sources of income. Families with more than one adult have lower out-of-pocket child care costs and are less likely to have to limit their working hours. More than 75% of rural families are headed by a married couple, and these constitute only 7% of families living in poverty. On the other hand, people living in female-headed families (15%) have the highest poverty rates (37%), which is 10 percentage points greater than in female-headed families in metropolitan areas. The ERS attributes the high rate of poverty for female-headed families to “lower labor force participation rates, shorter average work weeks, and lower earnings” (USDA, 2004b).

Rural poverty: children

Children are particularly vulnerable to outcomes of poverty and are among the poorest citizens in rural America, constituting 36% of the overall population of rural poor in 2003. The heaviest concentrations of child poverty are in the South and West. Understanding how poverty is distributed in rural populations is important for planning and delivering programs that ameliorate the impact of poverty, such as food stamps, school lunch programs, school health nursing interventions, and health insurance coverage (USDA, 2005).

When race and ethnicity are taken into account, the poverty profile of children worsens dramatically. Racial and ethnic minorities fare far worse than the general rural population of children from birth to 18 years of age. When family composition is taken into account, we find that almost half of non-Hispanic black children, 34% of Native American children, and 18% of rural children who live in a female-headed household are poor (USDA, 2005).

Health Risk, Injury, and Death

Health behaviors vary along the rural-urban continuum and within rural populations by geographic area. For example, researchers have noted that adults in nonmetropolitan areas use seat belts less often and are less likely to use preventive screening (although the latter trend is confounded by access problems). Elliot, Ginsburg, and Winston (2008) studied the prevalence of unlicensed teenaged drivers when compared with licensed drivers and found that they were more likely black or Hispanic and live in rural areas. Rural teens are equally likely as or more likely than both suburban and urban teens to report being victims of violent behavior, to have suicide behaviors, and to use drugs (Johnson et al., 2008). Rural residents in the Southern states are more likely to be obese, smoke more heavily if they do smoke, use smokeless tobacco, and engage in sedentary lifestyles. In the rural West, rates of smoking, seat belt use, and obesity are lower, and alcohol and smokeless tobacco use are higher (Eberhardt et al., 2001). For example, 19% of adolescents living in the most rural counties are smokers, compared with 11% in large metropolitan counties. Among adults living in the most rural counties, 27% of women and 31% of men smoke, compared with 20% of women and 25% of men in large metro areas. Tobacco use is increasing for men and women in the South.

Unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death in the United States for both sexes, for all races and ethnicities, and for all age groups from ages 1 to 44 years. Overall, unintentional injuries occur most often as the result of driving a vehicle (automobile, ATV, bicycle). In the latest available reports, unintentional injuries continue to be higher in rural areas of the United States. The mortality rate for unintentional injuries reported in the Urban and Rural Health Chartbook was 54.1 per 100,000 rural residents, which is twice the rate for large metropolitan counties (CDC Chartbook, 2007). Unintentional injuries are highest among males and in rural counties with the lowest population densities (Peek-Asa, Zwerling, and Stallones, 2004).

According to the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), unintentional injuries were ranked fifth in the leading causes of death in 2004. This category of death includes “transport accidents,” including motor vehicle accidents, and “non-transport accidents,” including falls, firearm accidents, drowning, fire-related deaths, accidental poisoning, and other accidental deaths (Hoyert et al., 2005). Males aged 15 to 24 years are the most likely victims of unintentional injuries.

In four of the least-populated states, the percentage of deaths from unintentional injuries was much higher than the national average, with 7.7% in Idaho, 8.0% in Montana, 9.1% in Wyoming, and 14.3% in Alaska. Overall, deaths from unintentional injuries were approximately 80% to 85% higher for females and males in the most rural counties than for suburban areas of metropolitan counties in 1996 to 1998, and highest of all in the West (Eberhardt et al., 2001). Driving at high speeds, driving long distances, driving in winter conditions, not using seat belts, and consuming alcohol have been cited as contributing to greater levels of injury deaths and disability by rural residents in the West. Lack of ready access to counseling, emergency medical services, and rehabilitation is also thought to be a contributing factor to these high levels.

Vulnerable Groups

Demographic and personal characteristics, such as age, education, gender, race, ethnicity, language, and culture, round out the examples of factors that affect health and may block access to existing services (Wang and Luo, 2005). Age is an important consideration in planning health care services for rural communities. As noted in previous sections, many retirees are moving into rural areas, and many younger people are moving out. Because the incomes of many elderly people may be lower, the tax base of counties and municipalities may be inadequate to cover the disproportionate share of the health care services used by the elderly (aged 65 years and over) (Eberhardt et al., 2001).

The population of elderly people is expected to double by 2050. Elderly women tend to live at or near the poverty level and achieve poverty status twice as often as men (USDA, 2005). Along with educational attainment, this is a critical indicator of well-being for the elderly and the young. The elderly poor tend to be isolated and lack access to support services, health care, prescription drugs, adequate nutrition, and transportation.

The number of children in rural areas increased by 3% in the decade from 1990 to 2000 (USDA, 2005). In addition to population growth, racial and ethnic diversity increased in the 1990s. Today, the proportion of Hispanic children is the fastest-growing component of the rural population, regardless of region. The population of black children has remained steady, and the majority of rural black children are still concentrated in the South. Native American children constitute only 3% of the total nonmetropolitan population, although in areas of the country (mainly West and Central) with high concentrations of Native Americans, this percentage is, of course, much higher. Evidence suggests that fetal, infant, and maternal mortality are slightly higher in nonmetropolitan than metropolitan areas and that care in the later prenatal stages is problematic. Nonmetropolitan children, like adults, are more likely to live in poverty, and proportionately fewer rural children were covered by health insurance in 2001 (Kandel and Cromartie, 2003; USDA, 2005).

Education and Employment

Research on the socioeconomic determinants of health has revealed a strong positive correlation between health and length of schooling (CDC, 2009). As Swanson (1999, p. 2) discussed, “Demographic characteristics of a minority group both affect and result from their economic and social status. Age structure and education combine as an indication of the level of employment a group might be able to enjoy.” For the aged and for ethnic and racial minorities, a pattern of lower educational attainment and unfavorable economic circumstances emerges with increasing rurality. Although the education picture is changing, many elderly women in their 70s and 80s grew up before public education was mandatory. Families could not afford to send them to school, or they were simply expected to learn to read and write, seek employment, and marry. Education, with its links to economic and health variables, is still a serious problem for rural America. Low education and employment levels characterize all rural minority groups except Asians. “Children of all racial and ethnic groups who live in precarious economic conditions have additional challenges to doing well in school and remaining in school through high school graduation” (Swanson, 1999, p. 4). In 2000, 77% of rural dwellers held high school diplomas or General Educational Development diplomas (GEDs) (compared with 70% in 1990) (USDA, 2005). The major difference between these two groups was in the percentage of rural students who held college degrees. The college completion rate of rural students was almost half that of urban students. There are also large gaps in educational completion by region, race, and ethnicity, with the West and Midwest students exceeding the high school completion rates of students in the rural South (USDA, 2005). Rural and central city students, especially minorities other than Asians, lag behind suburban children on most indicators of adequate progress in schools (IOM, 2005). Low educational attainment is a challenge in rural America. Skill requirements for rural employment continue to rise, lack of education is correlated with persistent poverty, and poverty is a predictor of poor health.

Furthermore, counties that have a low-wage economy have difficulty providing the infrastructure needed to provide education, public health, and health care services for low-wage families. They also have difficulty attracting new employers who might contribute to the economic development of a rural area, but need a more highly educated workforce.

Occupational Health Risks

In the United States, approximately 65,000 workers die each year of work-related illnesses and injuries (Herbert and Landrigan, 2000). Fatal occupational injuries declined 23.1% from 1992 to 2002. The rate (number of fatal injuries per 100,000 workers) decreased from 5.2 in 1992 to 4.0 in 2002 (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [NIOSH], 2004).

Occupational injuries, fatalities, and illnesses play a significant role in rural health, because rates of disabling injuries and injury-related mortality are dramatically higher in the rural population, particularly in the West and South (NIOSH, 2004). Industries with the highest death rates were mining, agriculture, forestry, and fishing, followed by construction, transportation, and public utilities (Eberhardt et al., 2001). The majority of job-related deaths due to workplace injuries in 2003 were in the following categories: transportation-related motor vehicle accidents, machinery-related events, homicides, falls, electrocution, and chemical and thermal injuries. Two industries accounted for more than 40% of fatal occupational injuries in 2002: construction (22.6%) and transportation and public utilities (18.3%). Three Western states, Alaska, Wyoming, and Montana, had the highest fatality rates (more than ten per 100,000 persons) for 2002 (Eberhardt et al., 2001).

Occupational death and disability can also be attributed to nonfatal injuries, and occupational diseases, such as cancer, asbestosis, silicosis, and anthracosis associated with both organic and inorganic exposures (NIOSH, 2004). Work-related injuries, deaths, and illness data must be interpreted with caution. Although surveillance of occupational injuries, illnesses, and fatalities has improved through the collaboration of the states and NIOSH, data still come from many sources, and underreporting continues to be problematic.

Perceptions of Health

Gender, Race, and Ethnicity

Both rural men and women are less likely than metropolitan residents to report their health as good or excellent. Rural areas, particularly in the rural South, have higher incidents of heart disease and cancer. Higher prevalence of chronic disease is consistent with the composition of rural populations, which tend to be older, poorer, and less educated (Gosschalk and Carozza, 2003). Rural men and women also smoke or use smokeless tobacco more. In the aggregate, they exercise fewer preventive behaviors, have less contact with physicians, and often have less access to care than people with similar problems in urban areas (Gamm, Castillo, and Pittman, 2003). Rural men and youths are also more likely to die or become disabled from unintentional injuries due to risky behavior or work-related causes and are more likely to commit suicide than women or urban men and youths.

Although rural populations overall are at lower risk for most cancers, certain rural subpopulations are at greater risk. For example, Appalachia has a much higher rate than the national figure. Residents in low-income areas and the uninsured, particularly African Americans, tend to have more late-stage cancer diagnoses; and rural residents in general may have less access to quality health care, including both medical care and screening and prevention programs (Gamm et al., 2003). A particularly serious problem for minorities and the elderly is the lack of cancer screening, including breast and cervical cancer for women and prostate cancer for men. Preventive care is especially important for African-American men, for whom prostate cancer is higher than for any other racial or ethnic group.

From 1987 to 2005, the age-adjusted percentage of women over 40 years of age who had a mammogram improved from 29% to 70.3% according to the CDC’s NCHS (CDC/NCHS, 2008). The percentage was lower for all racial and ethnic minorities, with 67.8% for African-American women and 47.3% for American Indian and Alaska Native women. Use of mammography was the lowest among the poor, most particularly in the 40- to 49-year-old age bracket (47.4%), and among the least educated (CDC/NCHS, 2008). Health objectives for the year 2010 called for at least 80% of American women aged 40 years and older to have received a mammogram and clinical breast examination in the previous 2 years (USDHHS, 2000). Similarly, women who are poor, elderly, and less educated are less likely to receive Pap tests. In racial and ethnic groups, the percentages of women who get Pap tests are lower for Hispanics, American Indians, and Alaska Natives. The lowest percentage is found in Asian women.

Rural-dwelling men suffer the long-term effects of having poor health habits, lacking consistent primary health care, and participating in hazardous occupations, as mentioned previously. Rural men in the South have higher rates of ischemic heart disease and cancer. Adult males on the whole were twice as likely as females to lack a usual source of health care in 2000 to 2001. In the West, the percentage of adults without a usual source of care was 19.4% in 2001 to 2002 and has changed little over the past 10 years (NCHS, 2008). In fact, among rural working-age adults, 45% of Hispanics, 32% of blacks, and 18% of whites were uninsured, and similar percentages had not visited a health care provider in the previous year (Glover et al., 2004).

Interacting with poverty and lack of access to care, rural minorities are among the nation’s least healthy citizens. African-American and Native American children and children of migrant workers are among the poorest of rural residents. By almost any measure or index (e.g., acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS] incidence, birth weight, blood pressure, cholesterol level, cancer incidence, and substance abuse), rural poor African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, and Alaska Natives are less healthy than whites. They also have food insecurity and hunger more frequently and have less access to quality health care (Probst et al., 2004).

The Indian Health Service, whose per capita expenditure for American Indian and Alaska Native health services is about half that of the U.S. civilian population, is the only source of health care funding for many rural American Indians. Marked disparities persist between American Indians and whites. American Indians have a death rate that is 1.5 times that of whites, and they are more likely to have a chronic health condition. These higher rates of morbid conditions use significant medical resources from both primary and specialty care physicians. In addition, rural American Indians are less likely to have private health insurance coverage, less likely to use health services, and more likely to have transportation difficulties. Among perceived barriers to rural American Indians’ access to important specialty services, financial constraints top the list (Baldwin et al., 2008).

The percentage of Hispanics and Latinos in the U.S. population was about equal to that of African Americans (12.5% vs. 12.3% during the year 2000), and Hispanics will soon become the largest minority group in the United States. They are already the predominant minority in the West. Hispanics have a diverse culture, history, and socioeconomic health status. The largest Hispanic subgroups are of Mexican, Cuban, and Puerto Rican descent, although Mexican is the largest by far (58% of the Hispanic population living in the United States). In nonmetropolitan areas, the population of Hispanics has doubled, and almost half of all Hispanics who live in rural areas are living outside the traditional areas of settlement in the Southwestern states. As emphasized previously, this growing segment of the population continues to be overrepresented among the rural poor. In 1999, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that just over 25% of Hispanics live below the federal poverty level, compared with 8.2% of the white, non-Hispanic population. Of those under age 18 years, the percentage living below the poverty level was 34% for Hispanics, compared with 10.6% of white non-Hispanics. The elderly were also 2.5 times more likely to live below the poverty line than white non-Hispanics. Hispanics are most likely to report barriers in obtaining needed health care and are least likely to have a usual source of care; for those blacks and Hispanics reporting a usual source of care, the source is most likely to be hospital based (Kass, Weinick, and Monheit, 1999).

Specific rural aggregates

Agricultural Workers

Health Disparities

An example of health disparities among agricultural workers is the group of farm workers that support fruit and vegetable production. In general, migrant and seasonal farmworkers (MSFW) may have the poorest health of any aggregate in the United States and the least access to affordable health care. Eighty-five percent of the MSFW are Hispanic, Latino, or African American. The rest are largely white seasonal workers who follow the harvests to drive combines or haul crops from the fields to storage, market, or seaports. These populations, estimated between 3 and 5 million people each year, are vulnerable to a host of health problems and diseases that center on occupational and environmental hazards and other health correlates, as described in the section about agricultural workers (USDA, 2008).

Accidents and Injuries

Working in highly variable environmental conditions (e.g., temperature extremes, a wide variety of work tasks, and unpredictable circumstances) is associated with an increased frequency of accidents and fatalities. Farm-related activities are extremely heterogeneous and vary significantly with the season, types of crops produced, and types of machinery used. Farmers are located in geographically isolated areas and often work alone. This constellation of factors places farmers and their families at increased risk for accidental injury and delayed access to emergency or trauma care.

The 2001 to 2002 rate of fatal injury for those employed in the agricultural sector was 21.3 per 100,000 workers, compared with a rate of 4.2 per 100,000 for all types of U.S. workers. According to NIOSH, agricultural machinery is the most common cause of fatalities and nonfatal injuries of U.S. agricultural workers, including on-farm fatalities among youth under 20 years (NIOSH, 2004). Tractor-related accidents, especially rollovers, are the most frequent causes of farm accidents and account for more than one fourth of farm fatalities. The actual causes of death and serious injury are associated with rollovers of equipment that lack rollover protective structures and seat belts (Struttmann et al., 2001). It is easy to see why accident prevention programs for farm children and families have focused heavily on tractor safety awareness.

Acute and Chronic Illnesses

Several types of farming activities are associated with higher than expected occurrences of acute and chronic respiratory conditions. Individuals with long-term exposure to grain dusts, such as grain elevator workers and dairy workers, have diminished respiratory function and increased frequency of respiratory symptoms (Pahwa et al., 2006; Cotton et al., 1989). Occupational asthma and more exotic fungal or toxic gas–related conditions also occur in higher frequency in agricultural than nonagricultural populations (Warren, 1989). Community health nurses, who are familiar with local farming practices in rural areas, often make links between farm work and respiratory symptoms. In such situations, the role of the nurse is to refer patients to appropriate health care providers and provide support and education for affected people and their families.

Exposure to pesticides, herbicides, and other chemicals is also a major concern for farmers and their families. From an occupational perspective, farming is unusual because the home and the work site are the same. Exposure risks to children and spouses may be heightened when farmers wear contaminated clothing and boots into the home. Homes are often located in close proximity to fields and animal containment facilities, which are treated with a variety of chemicals.

Nurses in rural emergency departments or other ambulatory care settings may be the first providers to encounter farmers and others with acute pesticide poisoning. During discussions with farmers, ranchers, or other high-risk groups (e.g., nursery workers and tree planters), community health nurses may note a pattern of headaches and nausea that occur during planting or spraying seasons. In such an instance, the nurse can serve as an important resource by obtaining a careful history of signs and symptoms, the temporal nature of symptom occurrence, and the types of pesticides and personal protection used (e.g., respirators and protective clothing). When evidence suggests pesticide-related illness, appropriate referral and follow-up are imperative to ensure the safety of the affected person and the family.

Signs and symptoms of acute pesticide poisoning are fairly clear, and most health providers in rural communities would recognize them. Common symptoms include headache, dizziness, diaphoresis, nausea, and vomiting. If left untreated, those affected may experience a progression of symptoms including dyspnea, bronchospasm, and muscle twitching. Deaths are relatively uncommon, but they do occur.

Altermanan et al. (2008) studied ethnic, racial, and gender variations among U.S. farmers and found a prevalence of musculoskeletal discomfort, followed by respiratory problems, hearing loss, and hypertension. Latino and Asian-American operators had lower prevalences of health problems than white non-Latino and white farmers. Hypertension and osteoarthritis were other risk factors include alcohol use (higher in rural areas and highest among persons living in the most rural areas, and more common among men than women), obesity (higher in rural areas, most particularly rural areas of the South), and physical inactivity during leisure time, which varies by level of urbanization and also by region for both men and women (highest level of inactivity in the South and in central counties of large metro areas of the Northeast) (Eberhardt et al., 2001).

Intentional injuries are most often the result of firearms usage. This can be against oneself or another. In rural counties, nonfatal firearm injuries occur most often at home compared with urban counties where injuries occur most often in the streets. Furthermore, numerous studies have noted that firearm suicide in rural counties is an important public health problem (Branas et al., 2005), and, according to the CDC, firearms are the most commonly used method of suicide among males.

Suicide is also a major public health problem in rural areas. In rural areas adjacent to a small city, suicide rates were 31% higher than suburban rates and 43% higher in rural areas that were not adjacent to small cities (Eberhardt et al., 2001). Nationally, suicide was the eleventh leading cause of death overall, eighth for males, and seventeenth for females. Little regional variation was found, except in the most rural parts of the West (especially in the least-populated states of Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho), where rates were 80% higher than those in metropolitan areas. There was also variation by race and ethnicity. Decreased access to mental health services for treatment of depression may contribute to these higher rates (Eberhardt et al., 2001). Among suicide victims, racial and ethnic disparities exist. Suicide rates among American Indians and Alaska Natives aged 15 to 34 years are 2.2 times higher than the national average for that age group, and Hispanic female high school students in grades 9 through 12 reported more suicide attempts (14.0%) than white, non-Hispanic (7.7%) or black, non-Hispanic (9.9%) students (CDC, 2008). The suicide rate for non-Hispanic white men 65 years of age and over is higher than in other groups. In 2004, the suicide rate for older non-Hispanic white men was about two to three times the rate for older men in other race or ethnicity groups and nearly eight times the rate for older non-Hispanic white women (CDC Chartbook, 2007).

Hypertension and osteoarthritis were more prevalent in black farmers, but they had a lower prevalence of hearing loss, skin problems, or heart problems. Cancer was less prevalent in black farmers than in white. In American Indian or Alaska Native farmers, musculoskeletal problems, skin problems, and hypertension were the most common.

Migrant and Seasonal Farm Workers

Although the discussion of agricultural issues has focused primarily on farmers and farm families, it is important to understand the role of migrant (i.e., migrate to find work) and seasonal (i.e., reside permanently in one place and work locally when farm labor is needed) farmworkers in U.S. agricultural production and the health risks to this population. Older references to farmworkers often referred to three “migrant streams,” in which workers entered the country through Mexico and migrated north. The present reality is that migrant workers enter the country through a variety of access points and follow any route necessary to obtain work. Seasonal workers permanently reside in agricultural areas and take various farm jobs during harvesting times. For example, a seasonal worker may be employed in restaurant work during the winter and may spend the summer months picking apples or working in a local apple shed or cannery (Branas et al., 2005).

MSFWs comprise a vulnerable population in regard to health risks because they have low income and migratory status. In many rural areas, community health nurses form the central link between farmworkers and health services. Through standing or mobile clinic sites, nurses have established a leadership role in the provision of episodic and preventive services for workers and their families. Lacking access to many types of preventive services, farmworkers often visit a migrant clinic with any number of health problems including severe dental problems, unresolved communicable diseases, and untreated injuries. In addition to the direct provision of care, nurses in many communities have served as important advocates on behalf of farmworkers and have worked to ensure health care access to those traveling through their areas.

Cultural, linguistic, economic, and mobility barriers all contribute to the nature and magnitude of health problems observed in farmworkers. Cultural and linguistic barriers are the most overt because many of the communities where farmworkers work consider them outsiders. In many settings, migrant workers live isolated from the agricultural communities they serve. Although some workers travel in extended family groups and have the support that comes with being together, other workers leave their families at home. Often these are male workers who work and live together. A common misconception among U.S. health care providers is that these farmworkers are from Mexico and Spanish is their primary language. Farmworkers originate from many communities in Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central and South America, and they may speak English, the language of their home country, or several languages.

Enumeration of Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers

To increase access to primary and preventive care for MSFW populations, information is needed on the numbers and distribution of farmworkers at the national, state, and local levels. Because MSFWs move frequently for work, census estimates generally provide a poor assessment of needs for health care services for this population. Additionally, the legislation that created the Migrant Health Program (MHP) (Section 330g of the Public Health Service Act), under the direction of the Bureau of Primary Health Care (BPHC) (2000) and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), requires that priorities be established based on where the greatest need exists. Hence the MHP has supported the ongoing and comprehensive assessment of the numbers of MSFWs and published the most recent estimates in the Migrant and Seasonal Farmworker Enumeration Profile Study (MSFWEPS) (Bureau of Primary Health Care, 2000).

Enumeration data from the MSFWEPS is available for Arkansas, California, Florida, Louisiana, Maryland, North Carolina, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Texas, and Washington. Although population sizes of MSFWs range from relatively small numbers in such states as Maryland and Oklahoma, to very large numbers in California and Washington, it is important to recognize that primary and preventive care services must be appropriately planned for those not engaged in farm and seasonal work, including other household members and children. For example, the state of California has an estimated population of 732,109 MSFWs, but an additional 570,688 nonfarmworkers must be considered in planning and evaluating services.

Health Needs and Opportunities for Preventive Care

Similarities in exposure and work practices make some of the farmworkers’ health needs similar to those of farmers and their families. Generally, these health needs reflect the increased rates of accidents and injuries, dermatological conditions, and pulmonary problems observed in both populations. However, there are additional challenges in both the identification and treatment of farmworkers with health problems. One of the biggest problems that nurses face in designing health programs is understanding the full magnitude of their problems. Many farmworkers who become ill eventually return to their countries of origin to obtain treatment and to be with family. This phenomenon makes it difficult to get complete, reliable numbers about disease rates. A variety of public health indicators are likely to undercount farmworkers as a group, ranging from tumor registries to Workers’ Compensation injuries (Schenker, 1995). In addition, farmworkers may be less likely to seek treatment for health problems that do not require emergency treatment or surgery.

Studies of farmworkers’ health status have provided data indicating that farmworkers are less likely to receive preventive care from any health source (Schenker, 1995). Preventive needs include dental care, vision screening and treatment, and gynecological and breast examinations. In addition, children of farmworkers are likely to receive incomplete sets of immunizations by the age of 5 years (Schenker, 1995). Many farmworkers, because they move from community to community, are often unaware of clinical and social services they could receive at reduced or no cost to low-income families.

Hearing Farmworkers’ Voices

Several studies and pilot projects have used focus groups, community meetings, or other qualitative research methods to listen to farmworkers’ concerns and give these concerns a voice through publication and advocacy. Several years ago, the Farmworker Justice Fund brought female farmworkers together in a national effort to give them a forum for their concerns and their impressions of health needs. The women identified priority concerns in the areas of child and family issues, health care services, workplace issues, and empowerment. The group’s recommendations in the area of health care included keeping clinics open during evening hours, providing transportation to clinics, increasing access through mobile health units, providing social and health services in one building, increasing home visits by students, encouraging careers in farmworker health, enhancing nutrition education to families, teaching first aid, enforcing farm labor health laws, and giving farmworkers a copy of the record after each clinic visit (Farm Worker Fund, 2006).

Involving MSFWs as active participants in the planning and provision of care may become more challenging since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Following this unprecedented event, policymakers began discussing broad changes to current immigration laws to protect the United States by securing the borders. In short, discussions have focused on limiting access of foreign workers to jobs in the United States and providing those already here with limited provisions for continuing in their current role. Concerns raised by public health advocates center around the idea that an increasingly punitive system of immigration will discourage seasonal workers and farmworkers from accessing health care or encourage them to lie to health care providers about critical issues (Mautino, 2004).

Application of relevant theories and “thinking upstream” concepts to rural health

Upstream and prevention-oriented approaches have several implications for nurses in rural practice. Three strategies for upstream interventions follow: attack community-based problems at their roots, emphasize the “doing” aspects of health, and maximize the use of informal networks.

Attack Community-Based Problems at Their Roots

Upstream approaches to community health problems direct the nurse toward an understanding of the precursors of poor health within populations of interest. Individual nurses can be effective forces in uncovering and enhancing community awareness of health-endangering situations. Environmental health issues in rural communities, such as pesticide exposure or health hazards from point-source factory emissions, are more effectively assessed and remedied on a community level than on a case-by-case basis. Nurses’ involvement in helping people understand health problems in a larger context can be the genesis of change. Nurses and other community members can take social action on behalf of those affected. For example, by heightening awareness of sulfur dioxide levels from a local refinery and the relationship of those emission levels to respiratory problems in vulnerable populations, nurses can help citizens gain an understanding of the collective rather than individual burden of the refinery on their community’s health.

Emphasize the “Doing” Aspects of Health

There are consistent differences between the ways rural and nonrural residents perceive health. The primary one may be the relative importance of “work” and “being able to work” in self-reported definitions of health (Weinert and Long, 1987). Rural attitudes generally emphasize the “doing” aspects of health by functioning and performing the daily activities fundamentally important in their daily lives. The high value placed on “being able to do” can provide astute nurses with intervention opportunities for both families and communities. Examples of nursing intervention strategies that capitalize on this include accident prevention programs for children, exercise and nutrition programs for seniors, and local industry participation in risk reduction programs for workers. Active involvement of the target population in all phases of program planning and implementation is key to the success of these programs.

Maximize the Use of Informal Networks

Recognizing and using informal networks in the community is essential to the “doing” concept of prevention programs. The name used, such as empowerment models or community action models, is less important than soliciting the involvement of informal networks and local leaders in planning health interventions. As most people who have been involved in community empowerment programs will attest, involvement of these important entities is not easy or straightforward. Turf issues and collateral agendas can obstruct rather than facilitate change. However, failure to elicit community involvement in population-based health interventions will result in unfavorable consequences. Frequently, superimposed change tends to fit poorly with the community it is intended to serve. Rural change strategies will be short-lived unless community members understand them and invest in their own well-being.

Rural health care delivery system

Health Care Provider Shortages

The Bureau of Health Professions (2003) states that the size and characteristics of the future health workforce are determined by the interaction of various forces acting on the health environment, including economic factors, technology, regulatory and legislative actions, epidemiological factors, the health care education system, and demographics. Current shortages of health care professionals in rural areas are likely to become worse with increased demand caused by population aging and increasing racial and ethnic diversity. In actual numbers, the shortage has been growing since 1990. Although approximately 25% of the U.S. population lives in nonmetropolitan counties, only 18% of registered nurses (RNs) practice there. In addition, the supply of physicians has not equaled service need in rural areas (Ferrer, 2007). For nonphysician primary care professionals, such as nurse practitioners (NP), physician assistants (PAs), and certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), trends are similar to those for physicians except for PAs. Hanrahan and Hartley (2008) report that 22% of NPs and 23% of PAs practice in urban areas. This pattern distribution has begun to resemble the distribution of physicians and other clinicians with heavy concentrations in urban areas and a growing shortage in rural and underserved areas.

Clearly, the growing nursing shortage will affect all of America. This is both a supply and a demand shortage. Declining school enrollments, retirement of current nurses, and the increased need for care of an aging population make the situation especially critical (Sigma Theta Tau International, 2006). A survey by the American Organization of Nurse Executives found that in small hospitals, usually located in rural areas, it takes significantly longer to fill vacancies than in larger urban facilities (Thrall, 2007). Rural nurses earn less than their urban counterparts, which compounds recruitment difficulties. Nurses with baccalaureate and master’s degrees, other than master’s-prepared NPs, are compensated less for this additional education (Thrall, 2007).

A solution proposed for the shortage of health care providers is for rural communities to “grow their own.” A rural community, a group of small communities, or a county could support local students attending college and recruit students currently attending professional schools. The students make a commitment to work in the community in return for monetary support for their educations (Thrall, 2007). Tuition reimbursement and access to distance learning programs can assist practicing nurses. Continuing education and baccalaureate and master’s degrees are available through e-mail, Internet-based courses, interactive video classes, and by-mail videos. Some programs are provided exclusively via the Internet. Nebraska rural communities are enthusiastic about the University of Nebraska College of Nursing Internet courses. The program is helping them grow their own nurses. Research shows that nurses educated in rural communities are more apt to stay and work there than those who move away to attend school (Pullen, 1998; Thrall, 2007).

Managed Care in the Rural Environment

Managed care has recently changed health care delivery in the United States. In rural areas, health care delivery networks with managed-care elements are being developed. Potential benefits and risks of managed care to rural areas have been identified, recognizing the difficulty for rural providers to deliver the cost-effective, complex health care needed from solo or small group practices. Possible benefits to managed care include lowering primary care costs, improving the quality of care, and stabilizing the local rural health care system. Risks are also apparent, including probable high start-up and administrative costs, and the volatile effect of large, urban-based for-profit managed-care companies (Allender, Rector, and Warner, 2010; Ricketts and Heaphy, 1999).

Outside of Medicaid, managed care has yet to become a major presence in much of rural America because of small dispersed populations, few visits per individual, and large numbers of elderly on Medicare with low-level reimbursements that do not make the aggregate financially attractive to a managed-care organization (MCO). In fact, despite the existence of federally qualified health centers that provide care to underserved populations through Medicare, Medicaid, or sliding fee scales, the reality is that there were few rural people enrolled in sponsored health plans (Allender et al., 2010). Providers in rural markets face severe financial constraints as HMOs increasingly cope with smaller numbers of enrollees and continue to decrease provider reimbursement (IOM, 2005). Communities that make the most progress toward partnerships or integration are those whose local leaders and providers have strong incentives to work together and are motivated to bring about change to the health care system. Authorities in rural health and managed care report that it is too soon to know whether managed care will become a significant way of delivering health care in rural areas, as it has become in urban America (Allender et al., 2010; IOM, 2005).

Community-based care

In the mid-1990s, the phrase community-based care became a popular term for the myriad of services provided outside the walls of an institution. Health care services are no longer provided exclusively in the hospital setting. Community-based care includes services that are provided where individuals live, work, or go to school. Examples of community-based services are home health and hospice care, occupational health programs, community mental health programs, ambulatory care services, school health programs, faith-based care, and elder services, such as adult day care. The concept also includes community participation in decisions about health care services, a focus on all three levels of prevention, and an understanding that the hospital is no longer the exclusive health care provider.

Home Care and Hospice

Home health and hospice programs vary in structure. In a national study on Medicare hospice use, only one third of rural counties have a hospice based within the county, but nearly two thirds of urban counties do (Virnig et al., 2004). Urban hospices are more likely to be freestanding, whereas rural hospices tend to be hospital based. Larger communities may support a hospital-based home care agency with hospice service, a freestanding, full-service agency, or both. In sparsely populated rural locations, home health and hospice services may be contracted from a larger regional agency, with a local nurse hired to provide services.

Virnig et al. (2004) found that the more remote the rural environment, the less likely hospice services were used. Nurse case management and development of local resources, using the county extension services as a bridge for outreach services, can improve home care for these patients and provide support for their families. A partnership between the public health nurse and county extension service could provide support and information groups and caregiving classes for the important informal provider network. Chapter 33 discusses home health and hospice in greater detail.

Faith Communities and Parish Nursing

Rural residents are perceived as having strong traditional values. At the heart of these values is a strong sense of community, family life, and religious faith (W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2001).

Since the conceptualization of parish nursing in the early 1980s, RNs have developed and expanded the role. Parish nurses integrate nursing expertise and faith-based knowledge to provide holistic care to members of congregations. More than 7000 nurses have completed formal training programs in parish nursing. The exact number of parish nurses working as paid and unpaid staff in both urban and rural faith communities is not known, because many nurses have not been formally prepared for the role (International Parish Nurse Resource Center, nd). Both professional nursing and parish nursing are based on health and healing (American Nurses Association, 2005).

In a comparison of experiences of rural and urban parish nurses, Chase-Ziolek and Striepe (1999) found rural nurses more likely to be involved in case management and coordination of services than their urban counterparts. In urban settings, contact with parishioners was primarily at the church, whereas contacts in rural settings were most often in the home, on the phone, or in other community-based settings. Collaboration between faith communities and other organizations can help extend limited rural community health resources. Such partnerships have been promoted by federal and state governments to enhance the public health efforts (Zahner and Corrado, 2004). Chapter 32 provides an in-depth discussion of faith community nursing.

Informal Care Systems

Limited availability and accessibility of formal health care resources in rural areas combined with self-reliance and self-help traits of rural residents have resulted in the development of strong rural community informal care and social support networks. Rural residents are more apt to entrust care to established informal networks than to new formal care systems (Weinert and Long, 1987, 1990). One study reported that rural residents sustain a higher level of social health than urban residents. They attributed this social health to their higher level of family and community involvement (Eggebeen and Lichter, 1993), which may contribute to the formation and use of informal systems.

Informal care systems or networks include people who have assumed the role of caregiver based on their individual qualities, life situations, or social roles. People who participate in these networks may provide direct help, advice, or information. Rural residents identify spouses, adult children, other family members, friends, and neighbors as informal providers of care (Buckwalter et al., 2002).