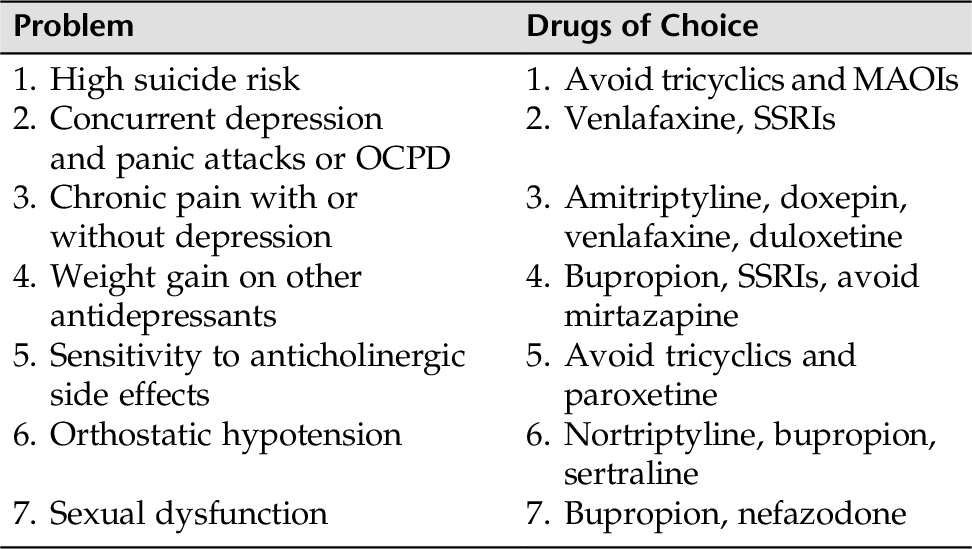

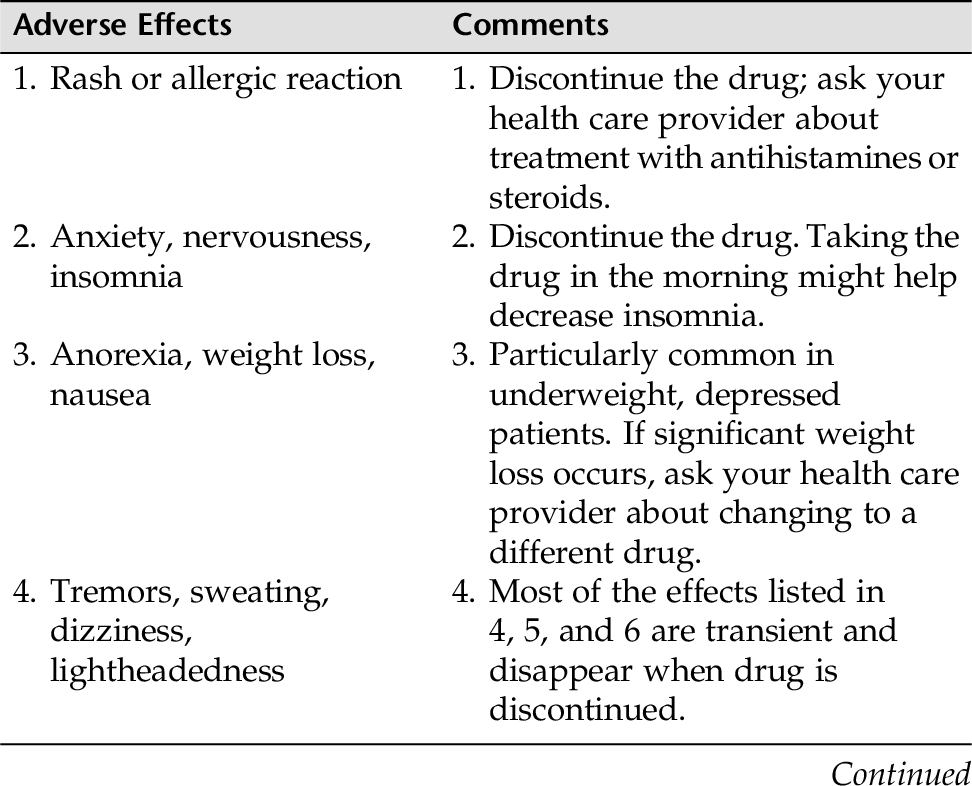

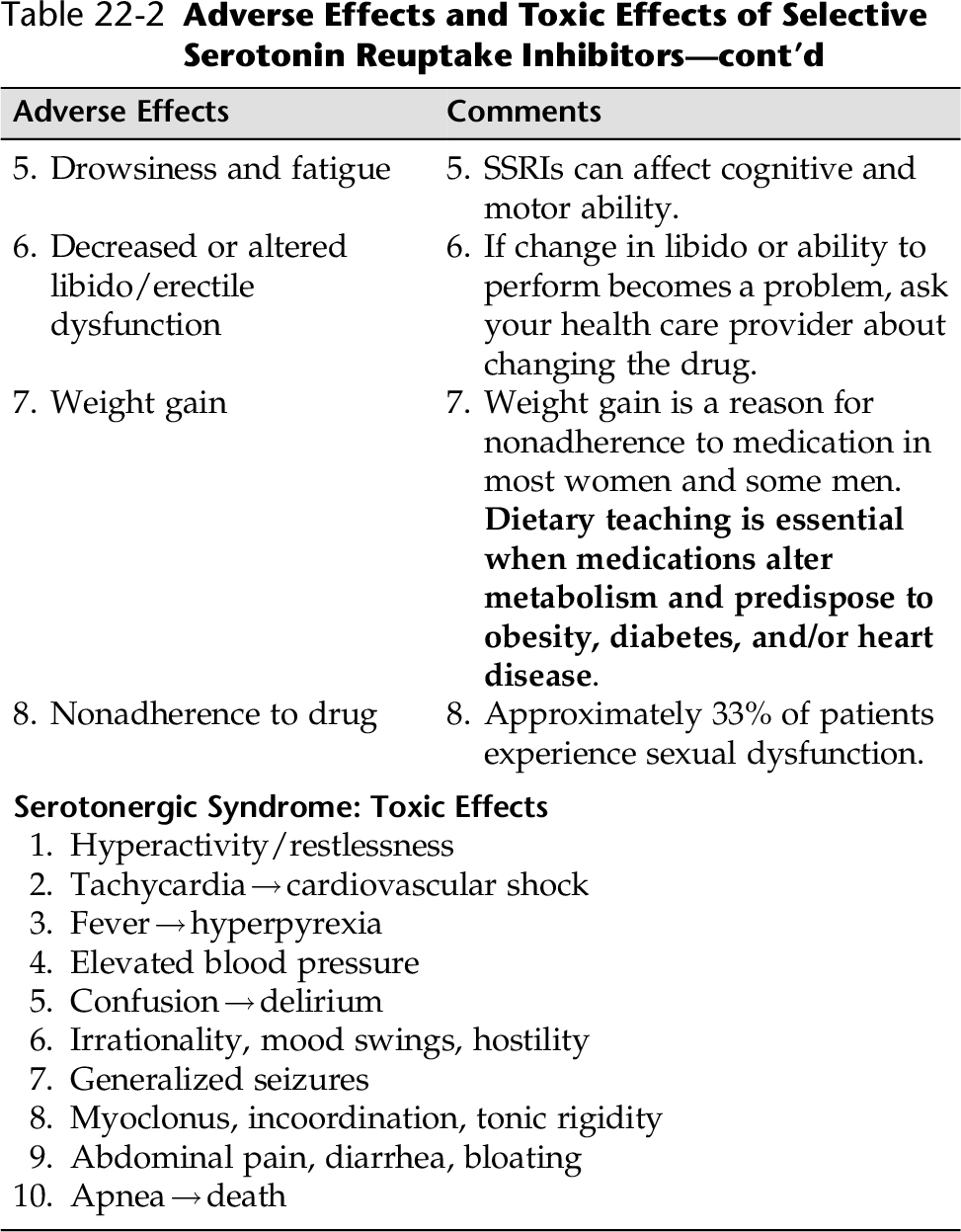

CHAPTER 22 Although the origins of a psychiatric illness are influenced by a number of factors (genetic, neurodevelopmental, psychosocial experience, infections, drugs), eventually an alteration in cerebral function occurs that accounts for disturbances in the patient’s behavior and mental experience (Varchol, 2013). Psychotropic drugs target these physiological alterations, and the reversal of these alterations is the goal of treatment (Varchol, 2013). Ideally, clinicians want a drug that will relieve the mental disturbance of patients without resulting in either mental or physical adverse effects. Unfortunately, as with all medications, the efficacy of a specific psychotropic drug might be accompanied by certain adverse effects or toxic effects. Therefore, it is important for nurses to understand which drugs help target specific mental symptoms, the potential adverse effects and toxic effects, and, of course, how to counsel patients and their families about: • Recognizing potential toxic effects and when to notify the health care provider • Situations in which these drugs are contraindicated or should be used with great caution • Any dietary or medication restrictions associated with a specific drug • How and when to take the medication to optimize the action of the drug and minimize the side effects and toxic effects • Discuss with the patient and family any concerns regarding compliance with the medication. Have the patient and family contact a health care worker if side effects or toxic effects arise that interfere with medication adherence. Some important guidelines that might enhance a patient’s medication adherence are listed in Box 22-1. In this chapter, the major classes of psychotropic drugs are reviewed. Within each class of drugs, the neurotransmitters targeted are identified. The neurotransmitter’s increase or decrease is responsible for the alleviation of symptoms; however, that same alteration of a specific neurotransmitter can also affect other systems and result in adverse effects. These adverse effects will be identified as well. To encourage patient adherence to medication treatment and protect the patient’s safety, patient and family teaching is vital. To aid in patient and family teaching, specific guidelines are provided for each of the major classes of psychotropic medications. This section introduces: • Non-benzodiazepines—Azapirones (BuSpar [buspirone]) The benzodiazepines have three main indications for use: (1) anxiety, (2) insomnia, and (3) seizure disorders. Benzodiazepines are also used for withdrawal from other drugs, and as an anesthetic. All benzodiazepines share the same pharmacological properties and produce a similar spectrum of responses. However, they differ significantly from one another with respect to time, course, or appropriate use. The downside of the benzodiazepines is that they are associated with impaired psychomotor function, cause depression in some individuals, and lead to tolerance and dependence in some individuals. For these reasons, they should only be used on a short-term basis. The SSRIs are considered the first-line treatment for anxiety. However, high-potency benzodiazepines should be considered only if the adverse effects of all other alternatives are unacceptable to the patient, or if the patient is unwilling or unable to wait out the 4- to 6-week delay in response associated with most antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs] or buspirone. Benzodiazepines are used for: • General anxiety disorder (GAD). The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are usually the drug of choice for GAD. However, benzodiazepines (alprazolam [Xanax]) may be used in severe cases of GAD, but the development of tolerance and dependence can be a serious issue, especially if used with alcohol or by those with a family history of alcohol abuse. Refer to Chapter 6 for psychopharmacology for GAD. • Acute anxiety: for short-term use. Best when used in conjunction with crisis intervention or other psychological interventions (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapies) • Treatment of acute mania—clonazepam (Klonopin) and lorazepam (Ativan) • As a short-term hypnotic and used short-term to help induce sleep—temazepam (Restoril), estazolam (ProSom), quazepam (Dural), zolpidem (Ambien), zaleplon (Sonata), and eszopiclone (Lunesta). Note: zaleplon and eszopiclone are non-benzodiazepines. • Muscle spasms: relaxes muscles—diazepam (Valium) • Seizure disorders. Anticonvulsant properties help suppress seizure activity—intravenous diazepam (Valium), lorazepam (Ativan), and clonazepam (Klonopin) • Treatment for sedative withdrawal syndromes (particularly alcohol withdrawal)—long-acting benzodiazepines such as diazepam (Valium) or chlordiazepoxide (Librium) • For sedation and amnesia prior to medical procedures—midazolam (Versed) is a short-acting benzodiazepine The benzodiazepines work by binding to specific receptors in a supramolecular structure known as the GABA receptor–chloride channel complex, thereby intensifying the effects of GABA in the central nervous system (CNS) (Lehne, 2013). Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is an inhibitory neurotransmitter found throughout the CNS. GABA plays a role in inhibition by reducing aggression, excitation, and anxiety. GABA also has an anticonvulsant and muscle-relaxing property and might play a role in pain perception. The effects of benzodiazepines are rapid, and there is a high margin of safety when they are used alone. However, since the downside of these drugs with long-term use can lead to dependency and tolerance, if stopped abruptly, withdrawal symptoms can be serious including panic, paranoia, delirium, and psychosis. For the usual daily doses for selected benzodiazepines and other anxiolytic agents, see Table 5-2 in Chapter 5. Benzodiazepines are metabolized by the liver. Oxidation can be impaired through hepatic cirrhosis, old age, or other drugs (cimetidine, estrogens, or isoniazid). Benzodiazepines can be classified as long-acting or short-acting. The faster-acting benzodiazepines are more likely to be abused. The long-acting benzodiazepines, such as chlordiazepoxide (Librium), clorazepate (Tranxene), diazepam (Valium), and prazepam (Centrex) have active metabolites with elimination half-lives of approximately 4 days. The longer half-lives can build up the amount of benzodiazepine in the system, which is not desirable, but the long-acting benzodiazepines can be discontinued suddenly without serious withdrawal symptoms. The short-acting benzodiazepines, such as Xanax (alprazolam), Ativan (lorazepam), and Serax (oxazepam), are quickly eliminated and have the potential for serious withdrawal reactions. Benzodiazepines depress neuronal function at multiple sites in the CNS and reduce anxiety through the effects on the limbic system. They promote sleep through effects on cortical areas, and on the sleep/wake cycle. Muscle relaxation is induced through effects on supraspinal motor areas, including the cerebellum. Two important side effects, confusion and anterograde amnesia, result from effects on the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. Central nervous system side effects produce: • Psychomotor impairment and drowsiness • Muscle weakness, ataxia, vertigo, confusion, sleepiness • Psychomotor impairment and falls, especially in older adults. • Cognitive and memory impairment • Acute anterograde amnesia • Impaired long-term memory from interference with memory consolidation, especially in older adults • Sedative effects. When taken alone within the proper dose range, benzodiazepines are relatively safe. However, benzodiazepines augment the sedative side effects of other sedatives, such as narcotics, barbiturates, and alcohol. When benzodiazepines are taken in combination with other CNS depressants, the combination can lead to respiratory depression, coma, and death. The benzodiazepines are weak respiratory muscle depressants and are usually safe when taken orally and without other CNS depression. Respiratory depression is most marked in individuals with CO2 retention, so people with pulmonary disease should have blood gases taken to test their PCO2 before a benzodiazepine is ordered. Respiratory depression is more apt to occur with IV administration of a benzodiazepine and, as mentioned earlier, in conjunction with other CNS depressants. When taken orally, there is no effect on the heart or blood vessels. However, when taken intravenously, benzodiazepines may produce profound hypotension and cardiac arrest. Although it is rare that the average individual with brief exposure to the drug becomes an abuser, the benzodiazepines are potentially drugs of abuse. Addiction-prone individuals are more likely to become physically dependent, therefore benzodiazepines should be prescribed for short-term use and with caution. Death from benzodiazepines alone is rare, but as previously emphasized, in combination with other CNS depressants, death from overdose can occur. Flumazenil (Mazicon), a benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, can reverse excessive sedation and psychomotor impairment. The long-acting benzodiazepines will often self-taper; the short-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., Xanax) should be tapered over several weeks or months. Slowly tapering the benzodiazepine helps prevent withdrawal symptoms (e.g., anxiety, insomnia, headache, muscle irritability, blurred vision, dizziness, delirium, paranoia, and psychosis). This is especially true if the patient has been taking high doses over a long period of time. The use of benzodiazepines is thought to cause a risk for congenital malformations in the fetus. Such risks include cleft lip, inguinal hernia, cardiac anomalies, and CNS depression. Benzodiazepines enter breast milk, so these drugs are best avoided by nursing mothers. • Cimetidine (Tagamet) • Low-dose estrogens • Disulfiram (Antabuse) • Isoniazid (INH) • Warfarin (Coumadin) • Digoxin (Lanoxin) • Anticholinergics • Alcohol and other CNS depressants • Kava kava • Patients with pulmonary disease should be medically evaluated (e.g., PCO2 level) • Used with caution in patients with hepatic or renal disease • Assess patient safety in depressed or suicidal patients • Evaluate for drug interactions • Pregnant and nursing women • History of substance abuse • Women of childbearing age if they become pregnant • Narrow-angle glaucoma • Concurrent alcohol or other CNS depressant use Refer to Box 22-2 for medication teaching guidelines for patients with anxiety disorders. The azapirone group is represented by buspirone (BuSpar). Buspirone differs from other anxiolytics in that it does not cause sedation, has no abuse potential, does not enhance CNS depression, and does not significantly interact with other drugs (except monoamine oxidase inhibitors [MAOIs] and haloperidol). For these reasons, buspirone is particularly useful in treating anxiety or mixed anxiety/depression. Its major disadvantage is that its anxiolytic effects can take several weeks to become effective. Therefore, it cannot be used as an as needed (PRN) medication. • General anxiety disorder (GAD) • General anxiety with accompanying depressive symptoms • Other uses Augments response to antidepressants • Augments response to drugs that treat obsessive compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) • May reduce the frequency and severity of episodic aggression in some populations with brain damage (developmentally disabled and demented) The mechanism of action for buspirone has not yet been determined. Buspirone does not seem to bind to GABA receptors (as do the benzodiazepines) but seems to show a high affinity for serotonin (5-HT) receptors and a low affinity for dopamine (D2) receptors in the CNS. The dosage range for anxiety is between 20 and 40 mg/day. (Note: The maximum recommended daily dosage is 60 mg, starting at 5 to 10 mg three times daily.) Buspirone undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism. Its metabolites are excreted primarily in the urine and, to a lesser extent, in the feces. The elimination half-life of buspirone might be prolonged in individuals with renal impairment and cirrhosis. These patients might require lower doses. Buspirone is well tolerated. The most common reactions (5% to 10% incidence) are as follows: Reactions include dizziness, drowsiness, headache, lightheadedness, and excitability. Reactions include nausea and, to a lesser extent, dry mouth, diarrhea, constipation, and vomiting. Buspirone has little or no effect on respiratory system, platelet, smooth muscle, and autonomic nervous system functions. NOTE: As previously stated, buspirone does not seem to instigate a physical or psychological dependency. No withdrawal symptoms seem to occur when the drug is discontinued, nor is there a cross-tolerance or cross-dependency with other sedative-hypnotics. • Might increase haloperidol levels Levels of buspirone can be increased by erythromycin, ketoconazole, and the ingestion of grapefruit juice (Lehne, 2013) • Patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding • Older adults • Debilitated patients • Patients with hepatic or renal dysfunction • Main contraindication: patients with a history of hypersensitivity to buspirone • Patients taking MAOIs or haloperidol Because of the lag time of several weeks, patients need to be supported through the first few weeks. They must be told to continue taking the drug, although they are not experiencing any changes as yet. Currently there is no conclusive evidence to demonstrate the clinical superiority of one group of antidepressants over another. One exception is the use of an MAOI for atypical depression, which can be highly effective for this disorder. The choice of medication is usually based on the side-effect profile and ease of administration. For example, if a patient is suffering from insomnia, a more sedative antidepressant might be ordered (e.g., mirtazapine). Conversely, if the patient is sleeping and lethargic, a more energizing antidepressant would be suitable (e.g. fluoxetine, bupropion). However, it might take trial and error to find a drug that will suit a particular patient. There are other considerations as well: • Safety is currently heatedly debated for use in depressed individuals younger than 18 years of age, especially in children. The FDA has issued a supplementary warning to follow all individuals closely who are on antidepressants. • When cost is a consideration, generic products are less expensive. • Past experience with a drug or the response of a first-degree relative can be a predictor of an effective medication regimen. • Most antidepressants are effective in the depressive phase of bipolar disorder; however, use caution because they all carry a risk for inducing mania. • If a single antidepressant action on serotonin (5-HT) or norepinephrine (NE) receptors is ineffective, a synergistic effect can occur when two independent antidepressant drugs are combined. Therefore, two antidepressants may be prescribed to target specific symptoms. • Antidepressant medications can take from 1 to 3 weeks or longer before symptoms are relieved. • Suicide is always a consideration when treating depression. Some patients might be given a limited supply initially to minimize taking an overdose. A precaution in hospitals is to make sure that the medication is taken and not “cheeked.” Table 22-1 presents an overall guide for an effective choice of antidepressant in patients with special needs. • Atypical antidepressants • TCAs • Second-line agents SSRIs are as effective as TCAs but do not have the troubling side effects of TCAs (e.g., hypotension, sedation, anticholinergic effects, cardiotoxicity). Overdose does not cause cardiotoxicity or death. The SSRIs are specific for serotonin (5-HT) reuptake blockage. The SSRIs currently carry an FDA supplemental warning for individuals younger than 18 years of age who may experience increased suicidal feelings with this drug group. • Major depression: All, except for fluvoxamine (Luvox) • Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD): fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), fluvoxamine (Luvox), paroxetine (Paxil) • Bulimia nervosa: fluoxetine (Prozac) • Panic disorder: sertraline (Zoloft), paroxetine (Paxil), fluoxetine (Prozac), citalopram (Celexa) • Social anxiety disorder: paroxetine (Paxil) • Premenstrual syndrome: fluoxetine (Prozac) As mentioned, the SSRIs specifically block the reuptake of 5-HT into the presynaptic cell from which it was originally released. Because these drugs are specific to serotonin and have little or no ability to block muscarinic and other receptors, they tend to have fewer untoward autonomic effects than the TCAs. They also do not cause cardiotoxicity or as much sedation. The primary pathway is hepatic metabolism. Impaired hepatic function is associated with impaired metabolism of SSRIs. There is also metabolic impairment with renal dysfunction. For this reason, a dosage adjustment is made for older adults and those with hepatic impairment. Common potential side effects include agitation, anxiety, sleep disturbance, tremor, sexual dysfunction (anorgasmia), and headache. The sexual dysfunction is significant (40% to 70%) and is a major reason for nonadherence in young men (Meyor & Quenzer, 2013). Common potential side effects are dry mouth, sweating, weight change, mild nausea, and loose bowel movements. Abrupt discontinuation of SSRIs can cause a withdrawal syndrome. Symptoms begin within days to weeks of discontinuing the medication. Therefore, tapering off is necessary. Withdrawal symptoms include dizziness, headache, nausea, sensory disturbances, tremors, anxiety, dysphoria, insomnia, and vivid dreams. Central serotonin syndrome is a rare and life-threatening event related to overactivation of the central serotonin receptors. This can occur when MAOIs or other drugs that increase the levels of serotonin in the brain are taken concurrently or within 2 weeks of each other. Symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, tachycardia, elevated blood pressure, delirium, myoclonus, increased motor activity, irritability, hostility, and mood change. Severe manifestations can induce hyperpyrexia, cardiovascular shock, and death. Refer to Table 22-2 for an overview of the adverse effects and toxic effects of SSRIs.

Major Psychotropic Interventions and Patient and Family Teaching

OVERVIEW

ANTIANXIETY/ANXIOLYTIC MEDICATIONS

Benzodiazepines

Therapeutic Uses

Mechanism of Action

Clinical Dosage

Metabolism

Adverse Effects

Central Nervous System

Respiratory System

Cardiovascular Effects

Potential for Abuse

Overdose

Discontinuing Benzodiazepines

Pregnancy

Drug Interactions

Drugs That Increase Benzodiazepine Levels

Drugs Whose Levels Might Be Increased by Benzodiazepines

Drugs That Might Impair Benzodiazepine Absorption

Drugs That Potentiate Central Nervous System Depressant Properties

Use with Caution

Contraindications

Patient and Family Teaching

Non-Benzodiazepine Antianxiety Agents: Azapirones (Buspirone [BuSpar])

Therapeutic Uses

Mechanism of Action

Clinical Dosage

Metabolism

Adverse Effects

Central Nervous System

Gastrointestinal

Other Systems

Drug Interactions

Use with Caution

Contraindications

Patient and Family Teaching

ANTIDEPRESSANT MEDICATIONS

FIRST-LINE AGENTS

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

Therapeutic Uses

Unlabeled Uses

Mechanism of Action

Metabolism

Adverse Effects

Central Nervous System

Autonomic Nervous System Reactions

Withdrawal Syndrome

Central Serotonin Syndrome

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree