The Child’s Experience of Hospitalization

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

2. Identify various health care delivery settings.

3. Describe three phases of separation anxiety.

4. List two ways in which the nurse can lessen the stress of hospitalization for the child’s parents.

5. Discuss the management of pain in infants and children.

7. Contrast the problems of the preschool child and the school-age child facing hospitalization.

8. Identify two problems confronting the siblings of the hospitalized child.

9. List three strengths of the adolescent that the nurse might use when formulating nursing care plans.

10. Organize a nursing care plan for a hospitalized child.

11. Recognize the steps in discharge planning for infants, children, and adolescents.

Key Terms

clinical pathway (p. 480)

conscious sedation (p. 475)

emancipated minor (ē-MĂN-sĭ-pā-ĭd MĪ-nŭr, p. 484)

narcissistic (năhr-sĭ-SĬS-tĭk, p. 484)

personal space (PŬR-sŭn-ŭl spās, p. 477)

pictorial pathways (p. 480)

regression (rē-GRĔSH-ŭn, p. 475)

respite care (RĔS-pĭt kār, p. 485)

separation anxiety (sĕpă-RĀ-shŭn ăng-ZĪ-ĭ-tē, p. 472)

transitional object (trăn-ZĬSH-ŭn-ŭl ŎB-jĕkt, p. 481)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

Health Care Delivery Settings

Outpatient Clinic

Many hospitals today have well-organized outpatient facilities and satellite clinics for preventive medicine and care of the child who is ill. The advent of Medicaid and other such programs has made these services available to low-income families. Within clinics, there may be specialty areas (particularly at children’s facilities) such as well-child clinics, asthma clinics, cardiac clinics, and orthopedic clinics. In some institutions, information is distributed and brief classes are held for waiting parents.

In many private medical offices the pediatricians or their nurses are available at certain hours of each day to answer telephone inquiries. The pediatric nurse practitioner may visit patients in the home, give routine physical examinations at the clinic, and otherwise work with the physician so that a higher quality of individual care may be attained. The nurse practitioner is often the primary contact person for children in the health care system.

Types of Outpatient Clinics

Satellite clinics are convenient and offer families flexible coverage. Some are located in shopping malls. Parents may walk with children and be contacted by a beeper when it is their turn to see the health care provider. This eliminates confining children in a small area and is less frustrating to caregivers. In many cities, a group of pediatricians practice in an office removed from the hospital, which aids in the distribution of health services and provides evening and weekend health coverage.

Another area of outpatient care is the pediatric research center, such as the one at St. Jude’s Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. This type of institution offers highly specialized care for patients with particular disorders, often at little or no expense to the patient. In the outpatient clinic, as in all other settings, documentation and record review are important parts of data collection.

For patients with uncomplicated conditions, elective surgery at an outpatient surgery clinic offers the advantage of lower cost, reduced incidence of health care–associated infection, and recuperation at home in familiar surroundings (e.g., herniorrhaphy or tonsillectomy). These outpatient clinics eliminate the need to separate the child from the family and reduce the extent of treatment and the emotional impact of the illness. Careful preparation must be given, and assurance must be obtained that the child’s home environment is adequate to meet recovery needs.

Promoting a Positive Experience

The attitude of nurses, receptionists, and other personnel in the clinic, office, or hospital unit is of the utmost importance. It can make the difference between an atmosphere that is warm and friendly and one in which the child is made to feel dehumanized. As more and more medical care is offered in outpatient clinics, there will be an even greater reduction in the number of children who require hospitalization. For many, the only exposure to medical personnel is through brief clinic appointments. Therefore it is very important that these encounters are positive ones for children and their families.

Preparing the Child for a Treatment or Procedure.

Whenever possible the parent should be involved in the preparation for and initiation of a treatment or procedure, and the child should be prepared according to his or her developmental level (Box 21-1). For example, for infants, have a familiar object stay with the infant, restrain as needed, and cuddle and hug the infant following the procedure. For a toddler, model the behavior desired (i.e., opening the mouth), tell the child it is okay to yell if the treatment or procedure is uncomfortable, and use distractions. For a preschooler, explain the treatment or procedure in simple terms, allow the child to handle some of the equipment, and keep other equipment out of sight. For a school-age child, explain in advance what the treatment or procedure is and the reason it is needed, and allow the child responsibility for simple tasks, such as applying tape. For adolescents, explain the treatment or procedure in more detail, and encourage questioning. Involve them in decision making and planning, such as who should be in the room. Proper preparation decreases anxiety, increases cooperation, and assists the child in coping with the experience.

Home

Because hospitalization is now brief for most children, the choice is not either hospital or home care but a combination of the two. They are becoming interdependent. Dramatic technical improvements and research in specific disease entities are also helping to advance the movement to home care (e.g., cryoprecipitate for hemophiliacs, Broviac catheters for chemotherapy, heparin locks for intravenous access, glucometers for monitoring blood glucose). However, home care is broader than in years past. It is not merely a matter of supplying appliances and nursing care, but it also includes assessment of the total needs of children and their families. Families need to be linked to a wide variety of network services. This ideally involves a multidisciplinary approach spearheaded by the health care provider.

The hospice concept for children has received accolades from parents who have benefited from its service. Local and national support groups for specific problems afford opportunities for families to share and support one another and to learn from others’ successes and failures. Special groups and camps for children with chronic illnesses are also well established. Group therapy for children under stress is equally important in preventing mental health problems (e.g., groups for children whose parents are divorced, Alateen for children of alcoholics). These and other programs not only have the potential for improving life for the child and family but also may help to reduce the high cost of medical care. There have been dramatic changes in the delivery of health care to children and families. These changes affect the role and responsibilities of the nurse working both in wellness centers providing preventive care and in hospitals or homes treating illness.

Children’s Hospital Unit

The children’s hospital unit differs in many respects from adult divisions. The pediatric unit or hospital is designed to meet the needs of children and their parents. A cheerful, casual atmosphere helps to bridge the gap between home and hospital and is in keeping with the child’s emotional, developmental, and physical needs. Nurses wear colorful uniforms, and colored bedspreads and wagons or strollers for transportation provides a more homelike atmosphere.

The physical structure of the unit includes furniture of the proper height for the child, soundproof ceilings, and color schemes with eye appeal. There is a special treatment room for the health care provider to examine or treat the child. In this way the other children do not become disturbed by the proceedings. Some hospitals have a schoolroom. When this is not available, it is necessary for the home-school teacher to visit each school-age child individually. Today’s modern general hospitals have separate waiting rooms for children. This is more relaxing for parents, because they do not need to worry about whether their child is disturbing adult patients, and it is less frightening to the child.

Most pediatric departments include a playroom. It is generally large and light in color. Bulletin boards and whiteboards are within reach of the patients. Mobiles may be suspended from the ceiling. Some playrooms are equipped with an aquarium of fish because children love living things. Various toys suitable for different age-groups are available. This room may be under the supervision of a child life specialist or a play therapist. Parents usually enjoy taking their children to the playroom and observing the various activities. The playroom is considered an “ouch-free” area, or a safe haven from painful treatments.

When the child is not able to be taken to the playroom because of the diagnosis or physical condition, bedside play activities appropriate to the developmental level and diagnosis of the child should be provided. The daily routine of the pediatric unit emphasizes parent rooming-in, the provision of consistent caregivers, and flexible schedules designed to meet the needs of growing children.

The Child’s Reaction to Hospitalization

The child’s reaction to hospitalization depends on many factors such as age, amount of preparation given, security of home life, previous hospitalizations, support of family and medical personnel, and child’s emotional health. Many children cannot grasp what is going to happen to them even though they have been well prepared. At a time when children need their parents most, they may be separated from them, placed in the hands of strangers, and even fed different foods. Add to this a totally new environment and physical discomfort, and the result is one frightened and unhappy child.

Each child reacts differently to hospitalization. One may be demanding and exhibit temper tantrums, whereas another may become withdrawn. The “good” child on the unit may be going through greater torment than the one who cries and shows feelings outwardly. The best-prepared nurse cannot replace the child’s parents. However, hospitalization can be a period of growth rather than just an unpleasant interlude. Children may see the nurse as someone who cares for them physically, as their parents would, and as a source of security and comfort (Figure 21-1).

The major causes of stress for children of all ages are separation, pain, and fear of body intrusion. This is influenced by the child’s developmental age, the maturity of the parents, cultural and economic factors, religious background, past experiences, family size, state of health on admission, and other factors.

Separation Anxiety

Separation anxiety occurs in infants age 6 months and older and is most pronounced at the toddler age. There are three stages of separation anxiety: protest, despair, and denial or detachment. Unless infants are extremely ill, their sense of abandonment is expressed by a loud protest. Toddlers may watch and listen for their parents. Their cry is continuous until they fall asleep in exhaustion. Toddlers may call out, “Mommy,” repeatedly, and the approach of a stranger only causes increased screaming. The crying gradually stops, and the second stage of despair sets in. Children appear sad and depressed. They move about less and withdraw from strangers who approach. They do not play actively with toys. In the third stage, denial or detachment, children appear to deny their need for the parent and become detached or disinterested in their visits. They become more interested in their surroundings, their toys, and their playmates. On the surface, it appears the child has adjusted to the separation. However, it is important for the nurse to understand that the child is using a coping mechanism to detach and reduce the emotional pain.

If the detachment stage is prolonged, an irreversible disruption of parent-infant bonding may occur. Health care workers who do not understand the stages of separation anxiety may label the crying, protesting child as “bad,” the withdrawn depressed child in despair as “adjusting,” and the child who is in the detachment phase as a “well-adjusted” child. This misinterpretation can prevent health care workers from providing desperately needed assistance and guidance to the child and family.

The nurse must understand that the child who is in despair reverts back to the protest stage when the parent arrives for a visit. Rather than showing joy, the child cries loudly when the parent appears at the door. This is good! The child who has reached the detached phase appears unmoved and uninterested in the parent’s arrival. Nursing interventions are needed in this case to preserve and heal parent-child relationships. Optimally the nurse helps the parents to understand they should not deceive the child into believing they will stay and then “sneak out” while the child is distracted. This can tear the bond of trust.

Pain

The accepted definition of pain is that “pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever the experiencing person says it does” (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2001). This includes verbal and nonverbal expressions of pain. Freedom from pain is a basic need and right of the infant and child. To increase awareness of pain during patient assessment, pain has come to be considered a “fifth vital sign.” An assessment for pain is recorded with routine vital sign documentation.

The negative physical and psychological consequences of pain are well documented. Patients in pain secrete higher levels of cortisol, have compromised immune systems, experience more infections, and show delayed wound healing. Nurses must maintain a high level of suspicion for pain when caring for children. Infants cannot show the nurse where it hurts, and often a child’s report of pain is not given the credibility of an adult’s report. In addition, children may not realize they are supposed to report pain to the nurse.

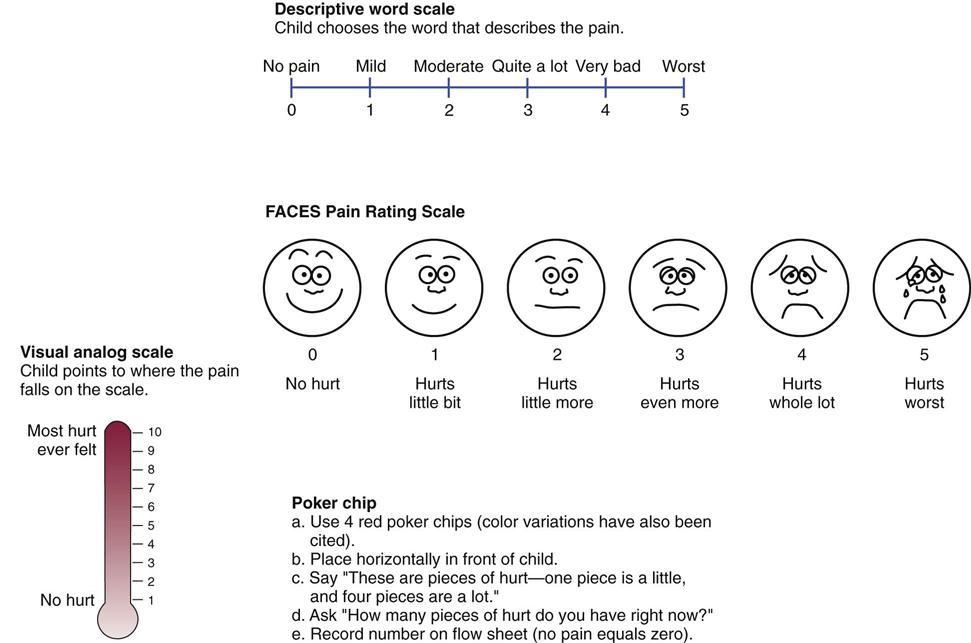

The nurse should ask the child about pain using a pain rating scale. See Figure 21-2 for sample pain assessment tools. Children may sometimes refrain from complaining if they believe they will receive an injection to relieve the pain. In infants, pain may be assessed according to a behavior scale that includes tightly closed eyes, clenched fists, and a furrowed brow (see Figure 12-8). Pain assessment tools for preverbal children are discussed in Chapter 12. In toddlers, crying may be caused by anxiety and fear rather than by the degree of pain. On the other hand, chronically ill children may not grimace or cry when in pain, but withdraw from interacting with their surroundings.

A pain indicator for communicatively impaired children (PICIC) has been developed and includes observations rated on a 4-point scale that includes the following:

The FLACC scale is a pain indicator that can be used with nonverbal children and is rated on a 0 to 2 scale for each observation with 10 being the highest level of pain; it includes the following:

All factors relating to pain assessment should be considered. Family members also experience emotional pain when they see their child in pain.

Nonpharmacological techniques such as drawing, distraction, imagery, relaxation, and cognitive strategies may enhance analgesia to provide necessary relief from pain symptoms. The child may draw “how the pain feels” and where it is located. Distractions such as storytelling, quiet conversation, and puppet play are effective. Imagery techniques, such as having children imagine themselves in a safe place, relieves anxiety. Slowing down breathing and listening to relaxation tapes is effective in reducing pain in adolescents. Cognitive (thinking) techniques such as “thought stopping” are also helpful in older patients. In this technique, the patient is instructed to repeat the word “stop” in response to negative thoughts and worries. A backrub or hand massage is also relaxing, depending on the child’s age and diagnosis. In newborns and infants undergoing brief painful procedures, oral sucrose may provide some analgesia. Pain medications should not be withheld from infants and children when needed.

Response to Drugs

Infants and children respond to drugs differently than adults. Elimination of the drug from the body may be prolonged because of an immature liver enzyme system. However, the renal clearance of drugs may be greater in toddlers than in adults. A decreased protein-binding capacity in the blood of small newborns may allow a greater proportion of free unbound drug to remain in the body of the small infant. Dosages are influenced by weight and differences in expected absorption, metabolism, and clearance. Every medication must be calculated by the nurse to determine the safety of the dose before the medication is administered. See the dosage calculation technique in Chapter 22.

Drugs Used for Pain Relief in Infants and Children

Acetaminophen is commonly used for the relief of mild to moderate pain in infants and children. The maximum dose is 15 mg/kg/dose for infants and children, with a maximum of 5 doses in 24 hours. Toxicity involves liver failure.

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Motrin), are given in a maximum dosage of 8 to 10 mg/kg every 6 hours (q6h). Ketorolac is a parenterally administered NSAID given for a maximum of 5 days.

Opioids are used for moderate to severe pain such as postoperative pain, sickle-cell crises, and cancer and should be administered with stool softeners to prevent constipation. If used for long periods of time, tolerance to the pain-relieving effect as well as respiratory depression effects can develop. The right dose of an opioid drug is the amount that relieves pain with a margin of safety for the child. The dose should be repeated before the pain recurs. Addiction is rare in children and adults receiving opioids for pain (Kliegman et al., 2007). Providing adequate pain relief enables patients to focus on their surroundings and other activities, whereas inadequate pain relief causes the patient to focus on the pain and when more medication will be given to stop the pain.

Fentanyl is a potent analgesic given for short surgical procedures. It has a rapid onset with a short duration of action.

Naloxone should be available for use in case of opioid overdose. Flumazenil (Romazicon) should be on hand for a midazolam (Versed) or diazepam (Valium) overdose.

Local anesthetics are used with safety and effectiveness in children. Topical anesthetics are used for skin sutures, intravenous (IV) catheter placement, and lumbar punctures. EMLA cream is a mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics) that is applied topically to the intact skin (Figure 21-3) and can be used with neonates. “Numby Stuff” uses a mild electrical current (iontophoresis) to push a topical preparation of Lidocaine and epinephrine into the skin providing local anesthesia within 10 minutes of the application of the patch. “LMX4” is a nonprescription topical anesthetic that is similar to EMLA. A vapocoolant spray can provide superficial skin anesthesia for short periods of time. Preoperative and postoperative care is discussed in Chapter 22.

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) allows the patient to press a button attached to an IV analgesic infusion to self-administer a bolus of medication. Parents and children as young as 7 years of age can be taught to use PCA. A built-in lockout interval prevents accidental overdosing. Any child receiving opioid analgesic drugs should be observed closely for side effects, such as respiratory depression.

More effective pain relief at lower dosages may be achieved when a low-dose analgesic is administered around-the-clock on a regular schedule rather than as needed (PRN). However, “breakthrough pain” can occur, and additional doses of an analgesic may have to be given. This type of pain management is called preventive pain control.

Conscious Sedation

Conscious sedation is the administration of IV drugs to a patient to impair consciousness but retain protective reflexes, the ability to maintain a patent airway, and the ability to respond to physical and verbal stimuli. Conscious sedation is used to perform therapeutic or diagnostic procedures outside the traditional operating room setting. A skilled registered nurse is required to continuously monitor the patient in an area where emergency equipment and drugs are accessible for resuscitation.

A 1 : 1 nurse-patient ratio is continued until there are stable vital signs, age-appropriate motor and verbal abilities, adequate hydration, and a presedation level of responsiveness and orientation. Parents are instructed concerning diet, home care, and follow-up visits.

Fear

Intrusive procedures, such as placing IV lines and performing blood tests, are fear provoking. They disrupt the child’s trust level and threaten self-esteem and self-control. They may make it necessary to restrict activity. Care must be taken to respect the modesty, integrity, and privacy of each child. Hospital personnel can provide an environment that supports the child’s need for mastery and control. These interventions are discussed according to age in this chapter and throughout the text. Selected nursing diagnoses for the hospitalized child and family are presented in Nursing Care Plan 21-1.