Populations Affected by Disabilities

Linda L. Treloar

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Differentiate between medical model and social construct definitions for disability.

3. Compare and contrast short- and long-term, health-related, disabling conditions.

4. Discuss key federal legislation applicable to people with disabilities.

Key terms

activities of daily living (ADLs)

ADA Amendments Act of 2008

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

children with a disability (CWD)

disability

functional activities

handicap

impairment

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

individualized education plan (IEP)

instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)

intellectual disability (ID)

people with disabilities (PWD)

reasonable accommodations

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)

Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

After having an incomplete spinal cord injury following an automobile accident, a 29-year-old man named Jim progressed from visible physical disability and paralysis to continued disability without the use of a wheelchair. Jim explained his progression, which follows:

You know it’s really weird. In some ways it’s hard to enter into that wheelchair life, to go into that life and then come back out of it again. I entered into a whole other realm [life with paralysis] that I’d only observed. I stepped into the unknown and pulled back out of it again. Yet, one foot is still in that world. (Treloar, 1999a, p. 189)

According to Jim, disability may create a “whole other realm,” or an “unknown” world. Like Jim, most people lack awareness of the divergence of perceptual worlds that disability creates and the historical, sociopolitical context and culture that surround disability. Nurses may think they understand disability, but this may not be true. Attitudes toward disability influence people’s responses to and care for others. Before reading further, consider the following self-assessment.

Self-Assessment: Responses to disability

What comes to mind when you think of someone with a disability? Focus on those sights, sounds, and smells. List characteristics using adjectives or short phrases. What values, customs, and traditions may be promoted or blocked for individuals with disabilities?

Picture yourself as a person with a disability. How do others respond to you? Who or what kinds of supports are available to help? Consider your health care concerns and needs. How might health care professionals devalue or disempower you? How can nurses and other caregivers convey respect and concern for you: to acknowledge insights gained through living with a disability, while helping to fill in the gaps where you lack wisdom?

Imagine yourself as a nurse with a visible disability, or the client receiving care from a nurse with a disability. What thoughts and feelings flood your mind? Would anything change if the nurse were invisibly disabled? Consider a scenario in which you apply as a preprofessional student with a disability to a college of nursing. Your disability requires additional time to achieve performance-based tasks. What might concern nursing program staff and faculty about this situation?

Think about living in a family affected by disability. Consider the impact of a child with a disability on sibling and parental activities and family roles. What if you were an active, growing child in a family where mom or dad is disabled? Although it may seem easier to focus on difficulties, consider possible benefits, to include positive learning and growth in family members. What kinds of social and personal supports do you have, or find are inadequate or lacking altogether? What do you wish others understood about living in a family affected by disability?

Finally, what is the experience of living with disability within your community? What social or environmental barriers related to disability exist? How can nurses and an interdisciplinary team form alliances with the client and family to reduce or eliminate these barriers? Health care professionals are taught to assess and provide interventions that promote health, and they usually believe they know what people with disabilities need. However, the actions of providers may convey different messages to people with disabilities and their families. Regardless of their professional experience or familiarity with disability, clients may question providers’ ability to understand their experience.

Disability affects people irrespective of class, culture, race, or economic level. Depending on the term’s definition, disability affects nearly one out of every five Americans. Disability increases with age, often influencing a person’s ability to maintain self-care, which is essential to living in his or her preferred living environment.

People who grow up with a disability describe their lived experience with disability somewhat differently from those who become disabled as the result of a health condition. For example, people having a sensory disability (blind/deaf), or a physical disability from birth, adapt to the world as they know it. Compare this situation with that of a 20-year-old who becomes blind, deaf, or paralyzed because of an accident. The loss may never be fully grieved. Adaptation may be delayed by the psychological impact of what is gone and its meaning. If an 80-year-old becomes blind because of diabetes-induced retinopathy, the loss of sight was chronic, progressive, and predictable. There will be loss and grief, but it occurs as part of the aging process. Rather than seeing people with disabilities (PWD) as “all the same,” nurses must be able to see each person with a disability as unique, having different goals, knowledge, and experiences.

This chapter provides content that nurses can use in a variety of settings to provide knowledgeable, appropriate care for people with disabilities and their families. Throughout your reading, consider: What implications exist for health care policy and research related to disability?

Definitions and models for disability

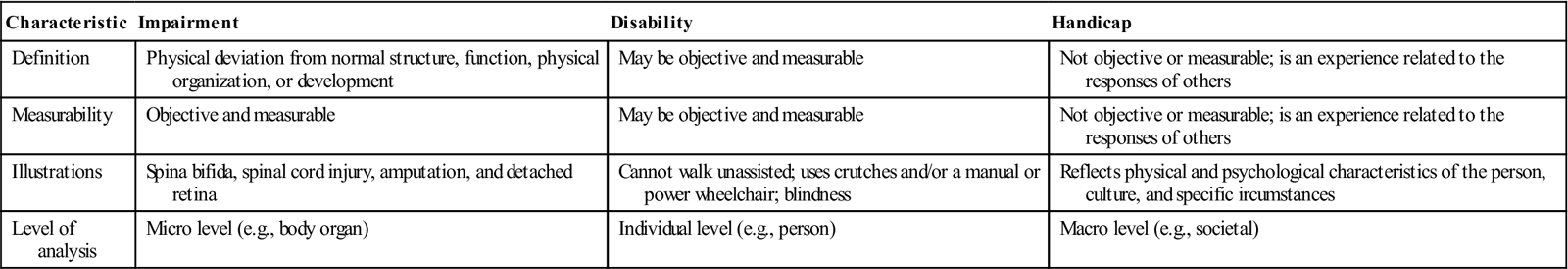

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (World Health Organization [WHO], 2001) defines the following key terms. A disability, resulting from an impairment, involves a restriction or an inability to perform an activity in a normal manner or within the normal range. An anatomical, mental, or psychological loss or abnormality is an impairment. A handicap is a disadvantage resulting from an impairment or a disability that prevents fulfillment of an expected role. In comparing these concepts, an impairment affects a human organ on a micro level, disability affects a person on an individual level, and a handicap involves society on a macro level of analysis (Batavia, 1993). Table 21-1 compares and contrasts these definitions related to disability.

TABLE 21-1

Terminology for Impairment, Disability, and Handicap

| Characteristic | Impairment | Disability | Handicap |

| Definition | Physical deviation from normal structure, function, physical organization, or development | May be objective and measurable | Not objective or measurable; is an experience related to the responses of others |

| Measurability | Objective and measurable | May be objective and measurable | Not objective or measurable; is an experience related to the responses of others |

| Illustrations | Spina bifida, spinal cord injury, amputation, and detached retina | Cannot walk unassisted; uses crutches and/or a manual or power wheelchair; blindness | Reflects physical and psychological characteristics of the person, culture, and specific ircumstances |

| Level of analysis | Micro level (e.g., body organ) | Individual level (e.g., person) | Macro level (e.g., societal) |

The “old” paradigm for viewing disability was based on the Nagi model, which used functional limitations to determine whether an individual was disabled (Pope and Tarlov, 1991). Although the WHO and Nagi frameworks recognize that a person’s ability to perform a socially expected activity reflects characteristics of the individual and the larger social and physical environment, they are commonly criticized for their medical emphasis and definitional inconsistencies. Impairments do not necessarily result in disabilities, and disabilities do not necessarily produce handicaps. Whether a person is viewed as disabled varies according to the environmental barriers and the perspectives of the onlooker.

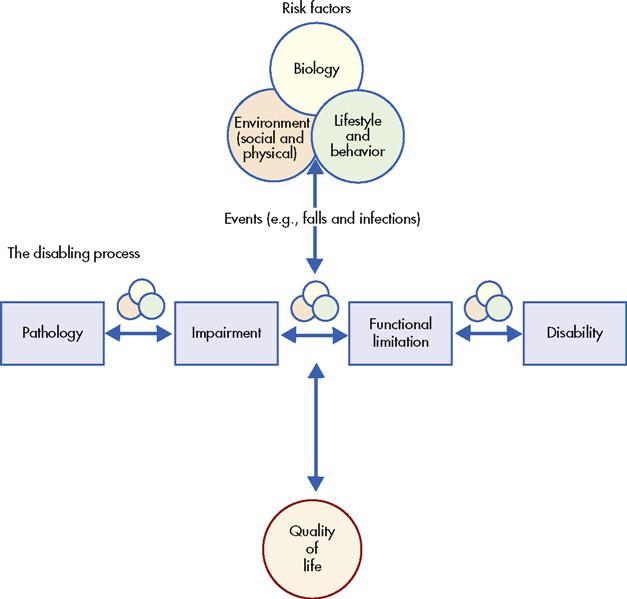

National Agenda for Prevention of Disabilities Model

The Committee on a National Agenda for the Prevention of Disabilities (NAPD) conceptualized a model for disability (Figure 21-1) that extends the ICF and Nagi frameworks. In the NAPD model, disability occurs when a person’s physical or mental limitations, in interaction with physical and social barriers in the environment, prevent the person from taking equal part in the normal life of the community (Pope and Tarlov, 1991). Furthermore, disability develops through a complex, interactive process involving biological, behavioral, and environmental (i.e., social and physical) risk factors and quality of life (QOL). In this social model for disability, bodily impairments and functional limitations are not necessarily accompanied by disability. Disability may be preventable, and preventive measures can promote an improved QOL and reduce costs related to dependence, lost productivity or unemployment, and medical care.

The Disabling Process

The NAPD model provides an alternative framework for viewing four related and distinct stages in the disabling process. Pathology at the cellular and tissue level may produce an impairment in structure or function at the organ level. An individual with an impairment may experience a functional limitation, which restricts his or her ability to perform an action within the normal range. The functional limitation may result in a disability when certain socially defined activities and roles cannot be performed.

Although the model appears to indicate unidirectional progression from pathology, to impairment, to functional limitation, to disability, stepwise or linear progression may not occur. Disability prevention efforts can address any of the risk factors or stages in the disabling process. Health promotion efforts include primary prevention of disability, secondary reversal of disability and restoration of function, and tertiary prevention of complications.

Quality of Life Issues

Accessing environmental and social barriers to needed services can frustrate and exhaust many PWD and their families. Barriers to access may include transportation to a needed service, the cost of care, appointment challenges, language barriers, financial issues (e.g., family has no phone to make or confirm appointments), and migrant/noninsured issues. Denied or delayed access to needed health services can negatively affect the health and well-being of any person. A PWD with an accompanying health concern may change a chronic concern into an acute problem. The Clinical Example (as follows) illustrates an attitudinal barrier and how it influences living with disability.

Community nurses can partner with clients and families affected by disabilities to remedy barriers that negatively affect QOL for this population. Most important, nurses must look beyond health-related concerns, a significant challenge in the current managed-care environment. Nurses cannot remedy health concerns without attending to interacting systems such as knowledge and educational background, personal and family belief systems, religious/spiritual beliefs and supports, finances, social networks, physical resources, and cultural influences.

Four Models for Disability

Disability is a socially constructed issue, and how it is perceived and understood often relates to perspective. Four models for viewing disability are described here:

1. Medical model—Disability is a defect in need of cure through medical intervention.

2. Rehabilitation model—A defect to be treated by a rehabilitation professional.

3. Moral model—Connected with sin and shame.

The medical and rehabilitation models would attempt to correct Cathy’s disability, whether that was indicated or desirable. The moral model would blame her for having a disability. Cathy had a college “friend” who repeatedly asked what “sin” in her life was unconfessed to God to remain unhealed. The socially constructed disability model recognizes that whether Cathy is perceived as able-bodied or disabled depends on the lenses through which she is viewed and the barriers that promote or prevent her participation to an equal extent with any other person.

Disability: A Socially Constructed Issue

Disability is a complex, multifaceted culturally rich concept that cannot be readily defined, explained, or measured (Mont, 2007). Whether the inability to perform a certain function is seen as disabling depends on socioenvironmental barriers, for example, attitudinal, architectural, sensory, cognitive, and economic, and inadequate support services and other factors (Kaplan, 2009).

Much of the complexity in defining disability stems from its socially constructed nature. . . . Because disability is more usefully conceptualized as the inability to perform important life functions, it becomes a product of interaction between health status and the demands of one’s physical and social environment. Thus, using a wheelchair is disabling in a workplace with steps and narrow doorways, but much less so in one with ramps and wide passageways. Similarly, cultural beliefs and attitudes shape the extent to which an impairment is disabling, and the extent to which people with physical or mental impairments are able to function in jobs and more broadly in public life. (Scotch, 1994, p. 172)

Differentiating Illness from Disability

The nurse must be able to differentiate between the person who has an illness and becomes disabled secondary to the illness, and the person who has a disability but may not need treatment. A disability is not necessarily accompanied by, nor related to, an illness; neither is an illness necessarily accompanied by, nor related to, a disability. Rather than assuming a need for treatment, the nurse should ask whether the client wants assistance, ask the client/family to describe the goal(s), and ask how and in what way(s) the nurse can help.

Hayes and Hannold (2007) wrote:

Although some persons with disabilities have recurrent health complications secondary to disability, the sole assignment of a disability label or diagnosis does not necessarily warrant the need for ongoing medical surveillance. Historically however, disabilities have been equated with sickness, and people with disabilities have been viewed as patients. The medicalization of disability has often relegated people with disabilities into a “sick-role” in which they are exempt from social role obligations and expectations of productivity, and instead, are viewed only as passive recipients of health care resources.

Persons with disabilities often confront “medicalization” issues when others view them in the “sick role” rather than as people first. Nurses who demonstrate understanding of these issues should approach PWD and their families on an eye-to-eye level; listening to understand, collaborating with the person/family, and making plans and goals that meet the other’s needs and that draw on strengths and improve weaknesses. This collaboration empowers and affirms the worth and knowledge of the person/family with a disability. This promotes self-determination and allows choices that foster personal values and preferences.

Characteristics of disability

Whether someone has a disability depends on the criteria used. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 define a disability by the limitations in carrying out a major life activity. Physical disabilities, sensory disabilities (e.g., being deaf or blind), intellectual disabilities (i.e., preferred terminology for mental retardation), serious emotional disturbances, learning disabilities, significant chemical and environmental sensitivities, and health problems such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and asthma are examples of disabilities that may substantially limit at least one major life activity. Major life activities include the ability to breathe, walk, see, hear, speak, work, care for oneself, perform manual tasks, and learn. The U.S. Census Bureau (2006) defines disability as a long-lasting physical, mental, or emotional condition that creates a limitation or inability to function according to certain criteria.

Measurement of Disability

To monitor changes in socioeconomic conditions for the general population, as well as for special populations, the government administers four household surveys. As definitions for disability change, so must measurement criteria. For example, the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) includes an extensive set of disability questions that include limitations in functional activities (e.g., seeing, hearing, speaking, walking, using stairs, and lifting and carrying items), activities of daily living (ADLs) (e.g., getting around inside the home, getting in and out of a bed or chair, bathing, dressing, eating, or toileting), and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (e.g., going outside the home, shopping, tracking money or bills, light housecleaning, and preparing meals). It gathers data on whether an individual uses an adaptive mobility device (e.g., wheelchair, cane, crutches, or walker) for 6 or more months; has a mental or emotional disability; has an impairment that produces on-the-job limitations or the inability to perform housework, or that involves the disability status of children (Brault, 2008).

The American Community Survey (ACS), having undergone extensive recent improvement, asks respondents whether they have a disability limitation that affects a certain function or activity, such as sensory perception, physical activities, mental and emotional state, self-care, ability to leave home, and employment options (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). The Current Population Survey (CPS), while not specifically designed to measure disability, asks questions to determine whether people are less able or unable to work because of a health condition or disability. Limited data relative to disability are collected from the Decennial Census of Population and Housing.

Prevalence of Disability

In 2005, approximately 54.4 million (18.7%) of the 291.1 million civilian noninstitutionalized population aged 5 years and older had a long-lasting condition or disability (Brault, 2008). Of those with a disability, 35 million (12%) had a “severe” disability. Further, it is important for health care policymakers and health care providers to recognize that the prevalence of disability is increasing.

Disability Prevalence by Race and Sex: 2005

U.S. Census Bureau SIPP data, June-September 2005 (Brault, 2008), indicate prevalence differences by race and sex. Blacks (20.5%) had a higher rate of disability when compared with Asians (12.4%) and Hispanics (13.1%), although it was not statistically different from that of non-Hispanic whites (19.7%). Females had a higher disability rate (20.1%) than males (17.3%) across all racial groups. However, higher disability rates in females can be explained by proportionally larger groups of older women as compared with older men.

Selected Measures of Disability

The U.S. Census Bureau collects data related to disability in communications, mental, and physical domains. Wheelchair users (15 years and older) comprised 1% of the population with a disability (Brault, 2008). An additional 3% of the population used a cane, crutches, and/or walker. In comparison, about 8 million people reported hearing and visual disabilities, a rate approximately twice that of wheelchair users. Collectively, more than 16 million people experienced a mental disability as defined by one or more of the following: a learning disability, intellectual disability, cognitive disability (dementia), other mental/emotional condition, and/or difficulty managing money/bills. An emotional disability, experienced by nearly 8.4 million people, included one or more of the following: depression and/or anxiety, interpersonal challenges, concentration difficulties, and/or difficulty coping with stress (Brault, 2008).

Prevalence of Disability in Children

According to the National Center for Health Statistics (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2008) about 21.8% of households with children have at least one child with a special health care need (disabling condition). Children with special health care needs received a broad range of comprehensive health services, including prescription medications (86%), specialty medical care (52%), vision care (33%), mental health care (25%), specialized therapies (23%), and medical equipment (11%). Preventive dental care was an unmet need reported by 16% of parents of these children.

Among school-aged children, almost 13% had a disability as defined by a communication-related difficulty, mental or emotional condition, difficulty with regular schoolwork, difficulty getting along with other children, difficulty walking or running, use of some assistive device, and/or difficulty with ADLs. Further, in this population, 4.4% had what would be termed a severe disability. Not being capable of doing regular schoolwork was the most prevalent disability affecting children (7.0%), and almost 6% had one or more selected developmental conditions. These included a learning disability, 2.8%; mental retardation (intellectual disability), 0.5%; other developmental disability, such as autism or cerebral palsy, 1.0%; and other developmental conditions that required therapy or diagnostic services, 2.9% (Brault, 2008).

Recommendations for the nurse

Community nurses who listen to parental concerns about their children establish what may be the most important bond they will have with a health care provider. Nurses should pay attention, particularly when parents intuitively whisper, “Something is not right.” A well-meaning health care provider may attempt to reassure a concerned mother. However, this kind of response may create silence and delay further questions by the parent. Rather than decrease parental concern, it may increase anxiety. The nurse can serve as an intermediary, working among the family and the health care team, to address parental concerns and client goals.

Whether working in a school or an office setting, the nurse should regularly assess for key developmental milestones and compare current status with predicted values. The school-aged child with developmental delays or disabilities should work with a team of resource providers, following an individualized education plan (IEP). If a child is not making progress, a parent has the right to ask for a change in the plan. Parents of children with disabilities frequently complain of fatigue associated with fighting “bureaucracies” tangled in rules that fragment, delay, or make services difficult to obtain. Similarly, parents may feel they are at “war” with schools when parental and organizational goals or plans for the child are in conflict.

Student learning activity

Parents taught their autistic son Tim to use sign language to communicate at home. However, public school staff rejected this communication mode. At age 8 years, Tim was mainstreamed, and, predictably, he was unable to use verbal communication. The child regressed, and his behavior deteriorated. The parents withdrew Tim when the school refused to modify the IEP. They planned to homeschool Tim, even though he required 24-hour-a-day supervision because he lacked safety awareness. Consider the family’s need for support. Other members include his father, who works 50 hours a week, and 6-year-old brother Roger who helps mom with Tim (Treloar, 1999b).

Break into small groups, and select one person to play the role of the mom. The highest priority goals should consider what key element? Establish three priority nursing diagnoses based on mom’s verbalized concerns and your assessment. Family and community resources should be assessed from a holistic perspective.

Mom’s assessment includes the following concerns:

Health Status and Causes of Disability

Chronic health problems are associated with aging and functional disability. Commonly, chronic respiratory conditions, hearing and vision disabilities, stroke, and fractures (both pathological, caused by osteoporosis, and accidental, from falls) increase with aging. Cognitive impairments, such as dementia, are recognized for their disabling potential. Americans in all age groups and cultures who are sedentary and overweight or obese are more likely to have type 2 diabetes develop. The nurse’s involvement in health promotion and disease prevention is critical. Regardless of the cause of disability, the nurse must see beyond the disabling impairment, carefully assessing affected persons’ perceptions of the disability experience. Ultimately, the personal belief system of the individual and the family and the traditions of the community influence the individual’s lived experience with disability and his or her participation in health care.

Aging and Personal Assistance

Disability prevalence and disability severity levels increase with aging. Thus, disability accompanies the “graying” of our elderly population, which is proportionately increasing as the “baby boomer” generation turns 65 years and older. In 2005, half (51.8%) of people aged 65 years and older had a disability, and 36.9% of people 65 years and older had a severe disability (Brault, 2008). The highest incidence of disability (71%) occurred in people 80 years and older; of these, 56% had a severe disability and 29.2% needed personal assistance. Not surprisingly, people in nursing facilities have a disability prevalence of 97.3% and a median age of 83.2 years.

Notably, the need for assistance with one or more ADLs or IADLs increases as severity of disability increases. In 2005, 11 million people needed personal care services (ADLs) and/or light housework assistance (IADLs). Community nurses are ideally qualified to provide care to individuals, families, and community neighborhoods through the use of strategies including evidence-based practice research application, case management, and team leadership.

Disability and public policy

Early American public policy viewed people with disabilities as “deserving poor” who required governmental protection and provision, with little capacity for self-support or independence (Rubin and Millard, 1991). Contemporary disability policy minimizes disadvantages and maximizes opportunities for people with disabilities to live productively in their communities. Public policy on disability includes civil rights protections (e.g., Title 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and the ADA), skill enhancement programs (e.g., special education, vocational rehabilitation, Ticket to Work and Work Incentives), and income and in-kind assistance programs (e.g., Social Security Disability Insurance [SSDI], Medicare, and Medicaid). Box 21-1 contains foundational values and ideologies that underlie public policy related to people with disabilities.

Legislation Affecting People with Disabilities

Consistent with historical and social changes and the recognition of barriers and discrimination, key federal legislation supports the rights of people with disabilities. The following section describes a few of the most significant acts.

The Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (PL 94-142) ensures a free appropriate public education to children with disabilities, based on their needs in the least restrictive setting from preschool through secondary education. Addressing special education needs requires appropriate evaluation and transition services. Parents, students, and professionals join together to develop an IEP that includes measurable special educational goals and related services for the child. See the IDEA website (http://idea.ed.gov/) for additional information.

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and ADA Amendments Act of 2008

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (PL 101-336) became law in July 1990. This landmark civil rights legislation prohibits discrimination toward people with disabilities in everyday activities (U.S. Department of Justice, 2009). The ADA guarantees equal opportunities for people with disabilities related to employment, transportation, public accommodations, public services, and telecommunications. It provides protection to people with disabilities similar to those provided to any person on the basis of race, color, sex, national origin, age, and religion. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is charged with enforcement for the employment provisions found in Title I of the ADA.

The ADA refers to a “qualified individual” with a disability as a person with a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities or bodily functions, a person with a record of such an impairment, or a person who is regarded as having such an impairment. The ADA prohibits discrimination against people who have a known association or relationship with an individual with a disability. A qualified individual with a disability must meet legitimate skill, experience, education, or other requirements of an employment position. The person must be able to perform the essential functions of the job, such as those contained within a job description, with or without reasonable accommodation(s). Qualifying organizations must provide reasonable accommodations unless they can demonstrate that the accommodation will cause significant difficulty or expense, producing an undue hardship.

Over time, judicial decisions eroded the ADA rights of people whose disabilities were intermittent, nonvisible, or manageable with medications, prosthetics, and/or medical equipment. On January 1, 2009, the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 (PL 110-325), a bipartisan bill supported by disability advocates and employers, became effective, making it easier for a person “seeking protection under the ADA to establish that he or she has a disability within the meaning of the ADA” (U.S. Department of Justice, 2009). For additional information, see the ADA website (www.ada.gov/).

The community health nurse should develop a resource network that includes disability resource center specialists, public interest law firms, and legal advocacy groups. High-priority interventions include helping people with disabilities learn about their rights and empowering them to act on their own behalf.

Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Improvement Act

Historically, national public policy has defined disability as the inability to work. Typically, people with disabilities could only qualify for such benefits as health care, income assistance programs, and personal care attendant services if they chose not to work. To address employment and benefit issues for persons with disabilities, in December 1999, the Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Improvement Act (TWWIIA) was signed into law. The TWWIIA reduced PWD’s disincentives to work by increasing access to vocational services and provided new methods for retaining health insurance after returning to work. Congressional efforts through the TWWIIA demonstrated evolution of attitudes and interest in PWD’s ability to work, potential economic contributions, and decreased reliance on public funds (Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Advisory Panel, 2007).

John, similar to many PWD, remains locked in poverty. John’s situation remains the “norm” despite the potential held by the TWWIIA. Complexity of rules, lack of awareness of work incentive provisions, fear of loss of health care and other support systems needed for work, and distrust associated with governmental operational issues are primary reasons the TWWIIA is poorly utilized (Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Advisory Panel, 2007). Change seems certain because Social Security Trust Fund resources will be inadequate to meet the needs of a rapidly aging baby boomer generation.

Public Assistance Programs

Public assistance programs include cash assistance (e.g., SSI, Social Security, and other cash assistance), food stamps, and public/subsidized housing. For people 25 to 64 years of age, participation in public assistance programs increased with severity of disability, consistent with the highest poverty levels. In 2005, 57% of people with a severe disability received public assistance, compared with 16.3% of people with a nonsevere disability, whereas only 7.3% of people with no disability received public assistance (Brault, 2008).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree