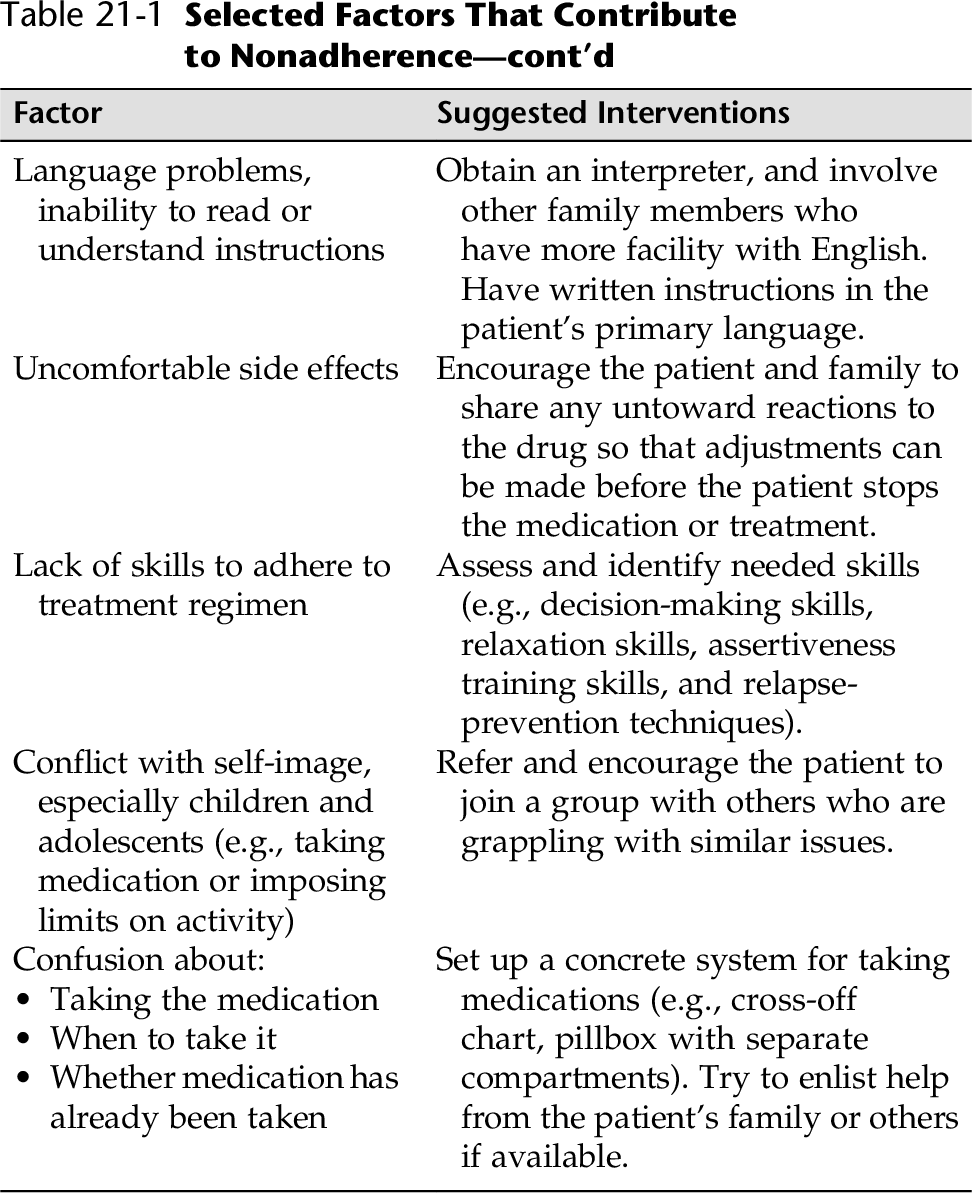

CHAPTER 21 When patients do not follow medication and treatment plans, they are often labeled as “noncompliant.” Applied to patients, the term noncompliant often brings with it negative connotations, because compliance traditionally referred to the extent a patient obediently and faithfully followed the health care provider’s instructions. “This patient is noncompliant” often translates into he or she is “bad” or “lazy,” subjecting the patient to blame and criticism. Crane (2012) cautions nurses and physicians not to be critical of noncompliant patients for being stubborn or a “bad” patient. This approach can leave both health care workers and patients frustrated and angry. The term noncompliant is invariably a judgmental term that implies the patientis at fault and insinuates that the health care system is free of blame. Crane (2012) also emphasizes that under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, documenting “noncompliance” no longer protects the physician, nurse, manager, or hospital for bad outcomes that have led to further illness or injury. The finding of noncompliance may render Medicaid or Medicare reimbursement not payable, which leads to financial loss to the institution and damage to the facility’s reputation (Brown, 2013). Furthermore, “patient did not comply” no longer protects health care workers from malpractice. Crane advises that meticulous records that document the provider’s “rationale for treatment, clear explanations of what he or she wants the patient to do, and whether the patient actually complied with that advice” will help prevent health care workers in malpractice suits (Crane, 2012). The takeaway is to treat noncompliance/nonadherence “as a serious issue that it is: each compliance issue, large and small, must be recognized as an indicator of potential trouble and must be addressed early and appropriately” (Brown, 2013). Perhaps the biggest issue in malpractice verdicts is when a patient is given instructions or a handout but states that he/she did not understand the instructions and/or states that he or she did not understand how important the treatment (e.g., medication, follow-up) was to their health. Adherence implies a more active, voluntary, and collaborative involvement of the patient in a mutually acceptable course of behavior. Rather than seeing the health care worker’s role as “getting a noncompliant patient to comply,” the nurse must negotiate and accommodate within the patient’s current understanding of the importance of the health regimen and social situation (e.g., ability to pay, support from family, supportive others)—in other words, find out what is making adherence difficult (Lerner, 1997). Therefore, the term nonadherence will be used here. Nonadherence to medications and treatment alone is not a problem. Nonadherence is usually a symptom of more complex, underlying problems. Although inadequate patient education is a common reason for nonadherence to a medical regimen, it is certainly not the only reason. Matejkowski and colleagues note the distinction between nonresponsivity and noncompliance (Matejkowski, et al. 2011). Many complex issues can complicate an individual’s willingness to follow a path leading to increased health or health maintenance. In a study of nonresponsivity with people taking antidepressants, forgetting was the most reported reason for noncompliance (Bullock et al., 2006). These issues, once addressed, can increase the patient’s adherence to his or her health care regimen. Table 21-1 presents selected factors that need to be uncovered and dealt with before medical adherence can be a reality. A positive history of nonadherence to medical regimen includes: • History of not keeping appointments • History of not taking medications • Escalation of signs and symptoms despite the availability of appropriate medication • History of emergency visits that are effectively treated with prescribed medication or treatment • Religious or cultural beliefs that contradict the patient’s medical/mental health care regimen • Poor outcome from past medical/mental health care treatments • History of poor relationships with past health care providers • History of leaving the hospital against medical advice (AMA) • Family members or friends state that patient is not adhering to prescribed regimen • Progression of disease/behaviors despite appropriate medication/treatment ordered • Fails to follow through with referrals • Fails to keep appointments • Denies the need for medication or treatment 2. Assess whether taking the medication will pose a financial problem for the patient. 3. Evaluate age-related issues interfering with adherence to medication/treatment protocols (see Table 21-1). 4. Assess for the presence of side effects of medication/treatment and how they affect the patient’s lifestyle. What would he or she like to change? 5. Does the patient believe that the medication/treatment regimen is really necessary? 6. Ensure that the directions for taking the medication are in the patient’s own language. 7. Determine what the patient identifies as the most difficult aspect of following through with the medication/treatment regimen? Nonadherence to medications or treatment can be voluntary or a result of a variety of factors that make adherence difficult (e.g., remembering to take medication). The nursing diagnosis of Noncompliance coincides with the active decision of an individual or family to fully or partially fail to adhere to an agreed-on medication/treatment regimen. In contrast, the nurse should emphasize the importance of negotiation and accommodation within the patient’s life situation. As mentioned, the term nonadherence frames the behavior more as a problem to be solved and not so much as willful, negative behavior. Ineffective Therapeutic Regimen Management refers to the difficulty or inability to regulate or integrate a medication/treatment plan into daily life. In this chapter, Nonadherence refers to noncompliance to a medical/psychiatric treatment regimen (the “why’s” yet to be determined), and Ineffective Family Therapeutic Regimen Management refers to situations in which the patient might be willing to comply but is having difficulty integrating the therapeutic regimen into his or her life or lifestyle. 2. Educate the patient. Provide information on the disorder, treatment options, medication side effects, and toxic effects using booklets, handouts, telephone numbers, and websites for further information. 3. After teaching, evaluate the patient’s understanding to clarify misunderstandings and reinforce requests. 4. Encourage the patient to keep active follow-up appointments and to call if an appointment will be missed. Definite follow-up appointments will enhance adherence. 5. Identify issues that might impede adherence to medications, and work out a needed intervention. For example, weight gain is often associated with many psychotropic agents. Dietary teaching is essential because many medications alter metabolism and predispose the patient to obesity, diabetes, and/or heart disease. 6. Provide feedback on progress, and acknowledge and reinforce efforts to adhere. 7. Refer the patient and family to a variety of resources for education, support, and assistance (e.g., pharmacists, health educators, medication groups, self-help groups).

Nonadherence to Medication or Treatment

Implications Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA)

OVERVIEW

ASSESSMENT

Assessing History for Nonadherence

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Assessment Guidelines

Nonadherence

NURSING DIAGNOSES WITH INTERVENTIONS

Discussion of Potential Nursing Diagnoses

Overall Guidelines for Nursing Interventions

Enhancing Adherence

Selected Nursing Diagnoses and Nursing Care Plans

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree