Transitions theory

Eun-Ok Im

“I believe very strongly that, while knowledge is universal, the agents for developing knowledge must reflect the nature of the questions that are framed and driven by the different disciplines about the health and well-being of individuals or populations”

(Meleis, 2007, ix).

Afaf Ibrahim Meleis

1942–present

Credentials and background of the theorist

Afaf Ibrahim Meleis was born in Alexandria, Egypt. In personal communication with Meleis (December 29, 2007), she reckons that nursing has been part of her life since she was born. Her mother is considered the Florence Nightingale of the Middle East; she was the first person in Egypt to obtain a BSN degree from Syracuse University, and the first nurse in Egypt who obtained an MPH and a PhD from an Egyptian university. Meleis admired her mother’s dedication and commitment to the profession and considered nursing to be in her blood. Under the influence of her mother, Meleis became interested in nursing and loved the potential of developing the discipline. Yet, when she chose to pursue nursing, her parents objected to her choice because they knew how much nurses struggle with having a voice and affecting quality of care. However, they eventually approved of her choice and had faith that Afaf could do it.

Meleis completed her nursing degree at the University of Alexandria, Egypt. She came to the United States to pursue her graduate education as a Rockefeller Fellow to become an academic nurse (Meleis, personal communication, December 29, 2007). From the University of California, Los Angeles, she received an MS in nursing in 1964, an MA in sociology in 1966, and a PhD in medical and social psychology in 1968.

After receiving her doctoral degree, Meleis worked as administrator and acting instructor at the University of California, Los Angeles, from 1966 to 1968 and as assistant professor from 1968 to 1971. In 1971, she moved to the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), where she spent the next 34 years and where Transitions Theory was developed. In 2002, Meleis was nominated and became the Margret Bond Simon Dean of the School of Nursing at the University of Pennsylvania.

Meleis, a prominent nurse sociologist, is a sought-after theorist, researcher, and speaker on the topics of women’s health and development, immigrant health care, international health care, and knowledge and theoretical development. She is currently on the Counsel General of the International Council on Women’s Health Issues. Meleis received numerous honors and awards as well as honorary doctorates and distinguished and honorary professorships around the world. She received the Medal of Excellence for professional and scholarly achievements from Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in 1990. In 2000, Meleis received the Chancellor’s Medal from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. In 2001, she received UCSF’s Chancellor Award for the Advancement of Women for her role as a worldwide activist on women’s issues. In 2004, she received the Pennsylvania Commission for Women Award in celebration of women’s history month and the Special Recognition Award in Human Services from the Arab American Family Support Center in New York. In 2006, Meleis was presented the Robert E. Davies Award from the Penn Professional Women’s Network for her advocacy on behalf of women. In 2007, she received four distinguished awards: an honorary doctorate of medicine from Linkoping University, Sweden; the Global Citizenship Award from the United Nations Association of Greater Philadelphia; the Sage Award from the University of Minnesota; and the Dr. Gloria Twine Chisum Award for Distinguished Faculty at the University of Pennsylvania for community leadership and commitment to promoting diversity. In 2008, she received the Commission on Graduates of Foreign Nursing Schools (CGFNS) International Distinguished Leadership Award based on outstanding work in the global health care community. In 2009, Meleis received the Take the Lead Award from the Girl Scouts of Southeastern Pennsylvania. In 2010, she was inducted to the UCLA School of Nursing Hall of Fame for her work in advancing and transforming nursing science.

Meleis’ research focuses on global health, immigrant and international health, women’s health, and the theoretical development of the nursing discipline. She authored more than 170 articles in social sciences, nursing, and medical journals; 45 chapters; and numerous monographs, proceedings, and books. Her award-winning book, Theoretical Nursing: Development and Progress (1985, 1991, 1997, 2007, 2011), is used widely throughout the world. In addition, her book entitled Women’s Health and the World’s Cities (Meleis, Birch, & Wachter, 2011) supports her recent efforts on health issues of urban women.

The development of Transitions Theory began in the mid-1960s, when Meleis was working on her PhD, and it can be traced through years of research with students and colleagues. In Theoretical Nursing: Development and Progress (Meleis, 2007), she describes her theoretical journey from her practice and research interests. Her master’s and PhD research investigated phenomena of planning pregnancies and mastering parenting roles. She focused on spousal communication and interaction in effective or ineffective planning of the number of children in families (Meleis, 1975) and later reasoned that her ideas were incomplete because she did not consider transitions.

Subsequently, her research focused on people who do not make healthy transitions and the discovery of interventions to facilitate healthy transitions. Symbolic interactionism played an important role in efforts to conceptualize the symbolic world that shapes interactions and responses. This shift in her theoretical thinking led her to role theories as noted in her publications in the 1970s and 1980s.

Meleis’ earliest work with transitions defined unhealthy transitions or ineffective transitions in relation to role insufficiency. She defined role insufficiency as any difficulty in the cognizance and/or performance of a role or of the sentiments and goals associated with the role behavior as perceived by the self or by significant others (Meleis, 2007). This conceptualization led Meleis to define the goal of healthy transitions as mastery of behaviors, sentiments, cues, and symbols associated with new roles and identities and nonproblematic processes. Meleis called for knowledge development in nursing to be about nursing therapeutics rather than to understand phenomena related to responses to health and illness situations. Consequently, she initiated the development of role supplementation as a nursing therapeutic as seen in her earlier research (Meleis, 1975; Meleis & Swendsen, 1978; Jones, Zhang, & Meleis, 1978).

The gist of Meleis’ works published in the 1970s defined role supplementation as any deliberate process through which role insufficiency or potential role insufficiency can be identified by the role incumbent and significant others. Thus, role supplementation includes both role clarification and role taking, which may be preventive and therapeutic.

With these changes in Meleis’ theoretical thinking, role supplementation as a nursing therapeutic entered her research projects. Her main research questions were to further define components, processes, and strategies related to role supplementation, which she proposed would make a difference by helping patients complete a healthy transition. This led Meleis to define health as mastery, and she tested that definition through proxy outcome variables such as fewer symptoms, perceived well-being, and ability to assume new roles.

Meleis’ theory of role supplementation was used not only in her studies on the new role of parenting (Meleis & Swendsen, 1978), but in other studies among post–myocardial infarction patients (Dracup, Meleis, Baker, & Edlefsen, 1985), older adults (Kaas & Rousseau, 1983), parental caregivers (Brackley, 1992), caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients (Kelley & Lakin, 1988), and women who were unsuccessful in becoming mothers and who maintained role insufficiency (Gaffney, 1992). These studies using role supplementation theory led Meleis to question the nature of transitions and the human experience of transitions. During this period, her research population interests shifted to immigrants and their health. This shift led Meleis to review and question transitions as a concept. Norma Chick’s visit to the University of California, San Francisco, from Massey University in New Zealand accelerated the development of the concept of transitions (Chick & Meleis, 1986) and Meleis’ first transitions article as a nursing concept.

To further develop this theoretical work, Meleis initiated extensive literature searches with Karen Schumacher, a doctoral student at the University of California, San Francisco, to discover how extensively transition was used as a concept or framework in nursing literature. They reviewed 310 articles on transitions and developed the transition framework (Schumacher & Meleis, 1994), which was later developed as a middle-range theory. Publication of the transition framework was well received by scholars and researchers who began using it as a conceptual framework in studies that examined the following:

• Description of immigrant transitions (Meleis, Lipson, & Dallafar, 1998)

• Women’s experience of rheumatoid arthritis (Shaul, 1997)

• Recovery from cardiac surgery (Shih, Meleis, Yu, et al., 1998)

• Family caregiving role for patients in chemotherapy (Schumacher, 1995)

• Early memory loss for patients in Sweden (Robinson, Ekman, Meleis, et al., 1997)

• Aging transitions (Schumacher, Jones, & Meleis, 1999)

• African-American women’s transition to motherhood (Sawyer, 1997)

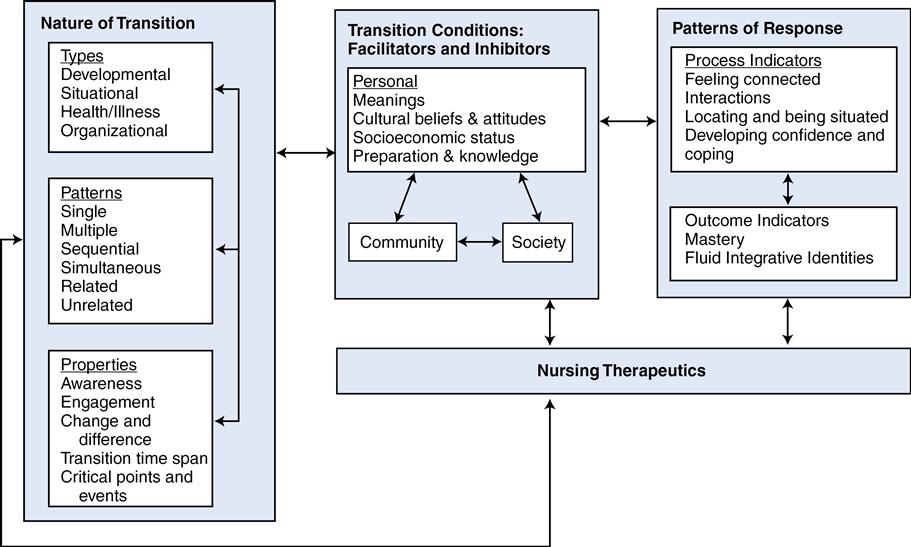

Using the transition framework, a middle-range theory for transition was developed by the researchers who had used transition as a conceptual framework. They analyzed their findings related to transition experiences and responses, identifying similarities and differences in the use of transition; findings were compared, contrasted, and integrated through extensive reading, reviewing, and dialoguing, and in group meetings. The collective work was published in 2000 (Meleis, Sawyer, Im, et al., 2000) and has been widely used in nursing studies. See Figure 20–1 for a diagram of the middle-range Transitions Theory.

Based on the early works of Transitions Theory, situation-specific theories that Meleis (1997) had called for were developed, including specifics in level of abstraction, degree of specificity, scope of context, and connection to nursing research and practice (Im & Meleis, 1999a; Im & Meleis, 1999b; Schumacher, Jones, & Meleis, 1999). For example, Im and Meleis (1999b) developed a situation-specific theory of low-income Korean immigrant women’s menopausal transition based on research findings, using the transition framework of Schumacher and Meleis (1994). Schumacher, Jones, and Meleis (1999) developed a situation-specific theory of elderly transition. Im (2006) also developed a situation-specific theory of Caucasian cancer patients’ pain experience. These situation-specific theories were derivative of the middle-range Transitions Theory. In 2010, Meleis collected all the theoretical works in the literature related to Transitions Theory and published them in a book entitled Transitions Theory: Middle-Range and Situation-Specific Theories in Nursing Research and Practice. In, 2011, Im analyzed the literature related to Transitions Theory and proposed a trajectory of theoretical development in nursing based on the theoretical works related to Transitions Theory in nursing.

Theoretical sources

Theoretical sources for Transitions Theory are multiple. First, Meleis’ background in nursing, sociology, symbolic interactionism, and role theory and her educational background led to the development of Transitions Theory as described earlier in the chapter. Indeed, findings and experience from research projects, educational programs, and clinical practice in hospital and community settings have been frequent sources for theoretical development in nursing (Im, 2005). A systematic, extensive literature review was another source for development of Transitions Theory as suggested by Walker and Avant (1995, 2005) for compiling existing knowledge about nursing phenomenon. Collaborative efforts among researchers who used the transition theoretical framework and middle-range Transitions Theory in their studies were a source for development of Transitions Theory. Finally, Meleis’ mentoring process could be another source for development of Transitions Theory. Meleis’ mentoring of Schumacher led to an integrated literature review through which the first Transitions Theory was proposed (Schumacher & Meleis, 1994). Also, the most recent version of Transitions Theory by Meleis Sawyer, Im, Schumacher, and Messias in 2000 could be also considered a product of mentoring students in the ongoing theoretical work.

Use of empirical evidence

In the development of the transition framework by Schumacher and Meleis (1994), a systematic extensive literature review of more than 300 articles related to transitions provided empirical evidence of the conceptualization and theorizing. Then, as mentioned earlier in the chapter, the transition framework was tested in a number of studies to describe immigrants’ transitions (Meleis, Lipson, & Dallafar, 1998), women’s experiences with rheumatoid arthritis (Shaul, 1997), recovery from cardiac surgery (Shih, Meleis, Yu, et al., 1998), development of the family caregiving role for chemotherapy patients (Schumacher, 1995), Korean immigrant low-income women in menopausal transition (Im, 1997; Im & Meleis, 2000, 2001; Im, Meleis, & Lee, 1999), early memory loss for patients in Sweden (Robinson, Ekman, Meleis, et al., 1997), the aging transition (Schumacher, Jones, & Meleis, 1999), African-American women’s transition to motherhood (Sawyer, 1997), and adult medical-surgical patients’ perceptions of their readiness for hospital discharge (Weiss, Piacentine, Lokken, et al., 2007).

Development of the middle-range theory of transition builds on empirical evidence from five research studies for conceptualization and theorizing (Sawyer, 1997; Im, 1997; Messias, Gilliss, Sparacino, et al., 1995; Messias, 1997; Schumacher, 1994). These studies were conducted among culturally diverse groups of people in transition, including African-American mothers, Korean immigrant midlife women, parents of children diagnosed with congenital heart defects, Brazilian women immigrating to the United States, and family caregivers of persons receiving chemotherapy for cancer. Empirical findings of these five studies provided the theoretical basis for the concepts of the middle-range theory of transition, and the concepts and their relationships were developed and formulated based on a collaborative process of dialogue, constant comparison of findings across the five studies, and analysis of findings. For example, one of the personal conditions, meanings, was proposed based on the findings from two studies (Im, 1997; Sawyer, 1997). According to Meleis Sawyer, Im, and colleagues (2000), although Korean immigrant midlife women had ambivalent feelings toward menopause in Im’s study, menopause itself did not have special meaning attached to it. Im found that most participants did not connect any special health/illness problems/concerns they were having to their menopausal transitions. Rather, women went through their menopause without perceiving any health/illness problems/concerns, which means that “no special meaning” might have facilitated the women’s menopausal transition. Yet, Sawyer’s study reported that African-American women related intense enjoyment of their roles as mothers and described motherhood in terms of being responsible, protecting, supporting, and needed. Thus, Meleis, Sawyer, Im, and colleagues (2000) proposed meanings as a personal transition condition because, in both studies, neutral and positive meanings might have facilitated menopause and motherhood. The middle-range theory of transition has been used in studies to develop situation-specific theories (Im, 2006; Im, 2010; Im & Meleis, 1999b; Schumacher, Jones, & Meleis 1999) and to test the theory in a study of relatives’ experience of a move to a nursing home (Davies, 2005).

Major assumptions

Based on Meleis’ former works on role supplementation, the transition framework by Schumacher and Meleis (1994), and the middle-range theory of transitions by Meleis, Sawyer, Im, and colleagues (2000), the following assumptions of Transitions Theory may be inferred.

Nursing