Care of Patients with Cardiac Disorders

Objectives

1. Compare left-sided and right-sided heart failure.

2. Describe the nursing assessment specific to the patient who is admitted with heart failure.

3. Identify life-threatening heart rhythms from a selection of cardiac rhythm strips.

6. State nursing responsibilities in the administration of cardiac drugs.

7. Describe under what circumstances cardiac surgery is appropriate treatment.

9. Develop a teaching plan with dietary recommendations for heart disease.

1. Develop a plan of care for a patient who has heart failure.

2. Perform a basic physical assessment on a patient who has a mitral valve stenosis and dysrhythmia.

3. Use the nursing process to care for assigned patients who have cardiovascular disorders.

4. Safely administer medications for patients with cardiac disorders.

5. Provide support to patients undergoing diagnostic testing and treatment for cardiac disorders.

6. Develop a teaching plan for patients with cardiac disorders.

Key Terms

ablation (ăb-LĀ-shŭn, p. 442)

arrhythmia (ă-RĬTH-mē-ă, p. 435)

atrial fibrillation (p. 437)

cardiac tamponade (KĂR-dē-ăk tăm-pŏn-ĂD, p. 443)

cardiomyopathy (kăr-dē-ō-mī-ŏp-ă-thē, p. 444)

cardioversion (kăr-dē-ō-VĔR-zhŭn, p. 440)

dysrhythmia (dĭs-RĬTH-mē-ă, p. 435)

effusion (ĕ-FŪ-zhŭn, p. 443)

ejection fraction (p. 428)

endocarditis (ĔN-dō-kăhr-DĪ-tĭs, p. 442)

friction rub (FRĬK-shŭn, p. 443)

infarct (ĭn-făhrkt, p. 435)

palpitations (păl-pĭ-TĀ-shŭnz, p. 435)

pericardiocentesis (pĕr-ĭ-KĂR-dē-ō-sĕn-TĒ-sĭs, p. 444)

pericardiotomy (pĕr-ĭ-KĂR-dē-ŏt-ō-mē, p. 444)

pulsus paradoxus (p. 444)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Disorders of the Heart

Heart Failure

There are about 5 million Americans with heart failure (HF), and approximately 670,000 are newly diagnosed each year. Approximately 1 in 100 people will develop HF. The prevalence of HF is increasing and it is a major chronic condition. Half of patients diagnosed with HF will die within 5 years. African Americans have a higher incidence of HF and have higher mortality rates than other populations. Heart failure can occur at any time the heart muscle is prevented from fulfilling its function as a pump and circulator of blood. Heart failure  may be acute or chronic, mild or severe. There are four stages of HF classed according to exercise tolerance (Table 20-1).

may be acute or chronic, mild or severe. There are four stages of HF classed according to exercise tolerance (Table 20-1).

Table 20-1

Classification of Heart Failure

| Class | Activity Tolerance |

| I | Ordinary physical activity with no symptoms |

| II | Dyspnea with long-distance walking, climbing 2 flights of stairs or strenuous activity |

| III | Dyspnea and fatigue with short-distance walking or climbing 1 flight of stairs |

| IV | Dyspnea at rest or with very little activity |

Adapted from the New York Heart Association Heart Failure Symptom Classification System. Retrieved from www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/cardiology/heart-failure.

Etiology

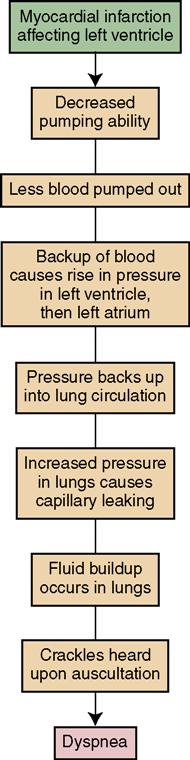

The most common causes of HF are coronary artery disease and uncontrolled hypertension. Other factors that contribute to weakness of the heart muscle are toxins, infection, anemia, myocarditis, dilation from blood backup behind diseased valves, and damage from myocardial infarction (MI) (Concept Map 20-1). Toxins include cocaine, excessive alcohol, certain chemotherapy

drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), thiazolidinediones used for diabetes, and doxazosin (Cardura) (Coviello, 2009). Cardiac dysrhythmias also can contribute to HF. (Coronary artery disease [CAD] and MI are covered in Chapter 21, along with cardiac surgery.)

Pathophysiology

The key words to understanding HF are congestion and increased pressure. Congestion develops because the heart is unable to move blood as quickly as it should. This may occur because the heart muscle is too weak or because the blood vessels throughout the body are narrowed and constricted (due to atherosclerosis or arteriosclerosis). Therefore the vessels cannot accommodate a normal supply of blood, causing the heart muscle to become exhausted trying to overcome the resistance (pressure) in the vessels. Poorly functioning valves may cause the chambers to dilate from blood backup, causing thinning of the myocardium and decreased pumping ability. Box 20-1 lists factors that precipitate HF.

Heart failure may be classified as right-sided HF or left-sided HF. The heart has two pumps: a right-sided and a left-sided pump. The right-sided pump receives blood from the body and pumps it to the lungs for oxygenation. The left-sided pump receives blood from the lungs and pumps it out to the body. Left-sided failure typically occurs first. Normally, the ventricles of the heart contract, while the atria relax, allowing for the filling and emptying of each chamber. If the muscle wall of the left ventricle cannot contract effectively, some of the blood is left in the ventricle—this residual blood prevents part of the blood in the left atrium from progressing into the ventricle. The blood that cannot leave the left atrium prevents the entrance of some blood from vessels, and, in turn, blood backs up into the pulmonary vessels. The pressure within those vessels increases, and fluid leaks into the lung tissue—producing congestion and, eventually, pulmonary edema. If not corrected, left-sided failure, because of the backup of blood and increased pulmonary artery pressure, will soon lead to failure of the right side of the heart. Table 20-2 compares the signs and symptoms of left-sided and right-sided HF.

Table 20-2

Comparison of Left-Sided and Right-Sided Heart Failure

| Right-Sided Heart Failure | Left-Sided Heart Failure | |

| Selected etiology | Pulmonary stenosis, pulmonary hypertension Severe emphysema, right ventricular MI | Hypertension, coronary artery disease, MI, mitral or aortic valvular disease |

| Pathophysiology | Increased pump pressure needed to eject blood into pulmonary arteries. The myocardium of the right atrium and ventricle becomes thickened, and contraction strength weakens | Weakness of the left ventricle resulting in reduced cardiac output and backup of blood into the atrium and the pulmonary system |

| Signs and symptoms | Fatigue; edema in sacrum, legs, feet, ankles; hepatomegaly; abdominal distention as a result of ascites; weight gain; dyspnea | Fatigue; dyspnea; wheezing; orthopnea; sleep apnea; pulmonary edema (pink, frothy sputum); pallor; clammy skin |

Primary right-sided heart failure is often caused by chronic pulmonary disease. If the right ventricle does not contract as strongly as it should, the ventricle cannot completely empty and becomes engorged with blood. More blood flow into the engorged ventricle causes overfilling and dilation of the chamber, slowing movement of blood out of the atrium. As blood in the atrium backs up, it prevents normal movement of blood flow from the vena cava, thus increasing the pressure in the vena cava, the neck veins, and all other veins of the body.

As the rate of blood flow slows down and pressure in the vessels increases, the fluid from the intravascular fluid compartment begins to leak into the interstitial compartment. This produces retention of fluid and edema. When the right side of the heart fails, the edema is first evident in the lower extremities (dependent or pitting edema; Figure 20-1). There also is an accumulation of fluid in the liver and abdominal organs, as the portal circulation becomes involved. Congestion of blood flow to and from the kidneys may lead to impaired renal function, preventing normal excretion of urine and causing more accumulation of body fluids. Inadequate circulation to and from the brain may cause mental confusion and irritability, which sometimes progresses to delirium and coma.

The systemic backup of blood that occurs in right-sided HF may eventually lead to left-sided heart failure, as the heart will have to pump against increasing pressure in the aorta and systemic circulation. The circulatory system is exactly that: a system. Failure of one component affects the entire system.

Left-sided heart failure is subdivided into systolic and diastolic heart failure. In the cardiac cycle, atria fill and allow blood flow to the ventricles; the ventricles fill and then eject blood into the circulatory system. Different problems cause failure of this process. Here the problems occur in the upper or the lower chambers of the heart.

Left-sided heart failure is subdivided into systolic and diastolic heart failure. In the cardiac cycle, atria fill and allow blood flow to the ventricles; the ventricles fill and then eject blood into the circulatory system. Different problems cause failure of this process. Here the problems occur in the upper or the lower chambers of the heart.

Systolic Failure

Systolic failure is caused by anything that interferes with ejection of blood from the ventricles. Muscle loss problems from MI, dilated cardiomyopathy, and aortic or pulmonic stenosis may lead to systolic failure.

Diastolic Failure

Diastolic failure occurs when conditions prevent the filling of the heart with blood. Tricuspid and mitral stenosis, cardiac tamponade, or constrictive cardiomyopathy can cause diastolic failure. Decreased filling results in decreased stroke volume and cardiac output. Ejection fraction is normal in primary diastolic failure. Ejection fraction is the percentage of the filling volume pumped out with ventricular contraction. A hallmark of diastolic failure is neck vein (jugular) distention.

Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

Initially, compensatory mechanisms prevent symptoms of HF. Heart rate rises to increase output and the ventricles hypertrophy in order to pump out more blood with each contraction. In left-sided failure compensatory mechanisms eventually weaken the heart and the blood backs up into the pulmonary vessels, pressure within those vessels increases, and fluid leaks into the lung tissue, producing congestion. Fatigue and shortness of breath (SOB) are first noticed with activity and when lying down. If failure progresses, pulmonary edema occurs. Diagnosis is made on the basis of history, examination, signs and symptoms, chest x-ray, echocardiogram, electrocardiogram (ECG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electrolytes, complete blood count (CBC), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). BNP measures the level of a protein released when myocardial cells are stretched. A level greater than 500 pg/mL is consistent with HF when other symptoms are present (see Table 20-2).

Advanced systolic HF signs are S3 and S4 heart sounds. Weight gain of 2 lb in 24 hours or 5 lb in 1 week occurs as fluid is retained. Dyspnea and crackles or wheezes are heard in the lungs.

Treatment

Treatment of the underlying cause of HF should be initiated. Dysrhythmias are controlled. Surgical correction of valve or septal abnormalities may reverse HF. Medical treatment is largely symptomatic and depends on the type and degree of HF present. Drugs and other therapies are used to reduce or eliminate the symptoms and complications of HF, but they only control the condition; they do not cure it. Efforts are made to (1) reduce the demand for oxygen and the workload of the heart; (2) strengthen the heart’s pumping action; (3) relieve venous congestion in the lungs; and (4) minimize sodium and water retention in the tissues (Jessup et al., 2009).

To accomplish the goals of medical intervention, the following may be prescribed:

• Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) decrease the workload of the heart by causing vasodilation; as a result, blood pressure is reduced (Table 20-3). ACE inhibitors and ARBs also play a role in reducing fluid retention.

• Morphine is prescribed if pulmonary edema is present to relieve anxiety and make breathing easier.

• Benzodiazepines may be used for anxiety and reduction of emotional stress.

• Limited physical activity or bed rest in semi-Fowler’s or high Fowler’s position.

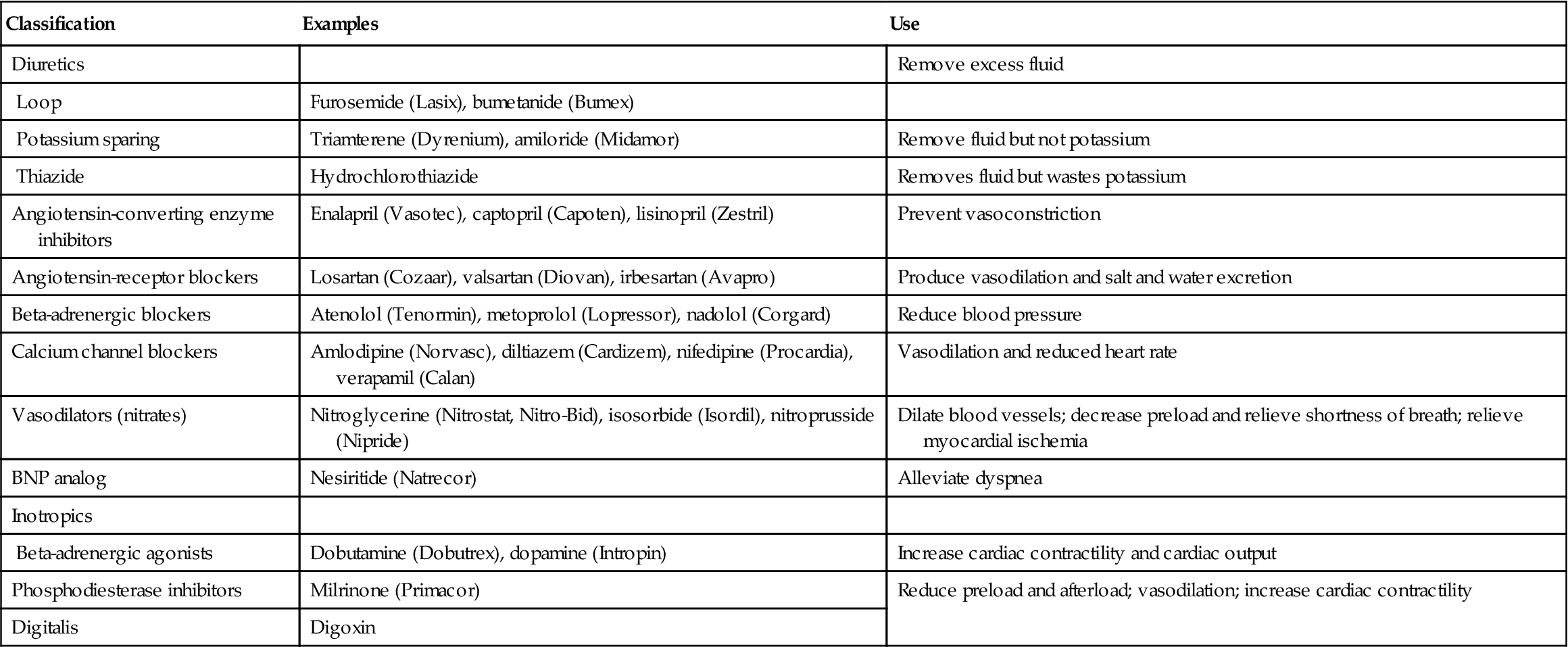

Table 20-3

Table 20-3

Drugs Used to Treat Heart Failure*

| Classification | Examples | Use |

| Diuretics | Remove excess fluid | |

| Loop | Furosemide (Lasix), bumetanide (Bumex) | |

| Potassium sparing | Triamterene (Dyrenium), amiloride (Midamor) | Remove fluid but not potassium |

| Thiazide | Hydrochlorothiazide | Removes fluid but wastes potassium |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | Enalapril (Vasotec), captopril (Capoten), lisinopril (Zestril) | Prevent vasoconstriction |

| Angiotensin-receptor blockers | Losartan (Cozaar), valsartan (Diovan), irbesartan (Avapro) | Produce vasodilation and salt and water excretion |

| Beta-adrenergic blockers | Atenolol (Tenormin), metoprolol (Lopressor), nadolol (Corgard) | Reduce blood pressure |

| Calcium channel blockers | Amlodipine (Norvasc), diltiazem (Cardizem), nifedipine (Procardia), verapamil (Calan) | Vasodilation and reduced heart rate |

| Vasodilators (nitrates) | Nitroglycerine (Nitrostat, Nitro-Bid), isosorbide (Isordil), nitroprusside (Nipride) | Dilate blood vessels; decrease preload and relieve shortness of breath; relieve myocardial ischemia |

| BNP analog | Nesiritide (Natrecor) | Alleviate dyspnea |

| Inotropics | ||

| Beta-adrenergic agonists | Dobutamine (Dobutrex), dopamine (Intropin) | Increase cardiac contractility and cardiac output |

| Phosphodiesterase inhibitors | Milrinone (Primacor) | Reduce preload and afterload; vasodilation; increase cardiac contractility |

| Digitalis | Digoxin |

See Table 19-3, Box 19-1, and Table 20-4 for further information and nursing implications for these drugs.

BNP, brain natriuretic peptide.

*The choice of drugs depends on the type of heart failure and whether the left ventricle function is normal.

• A left ventricular assist device (LVAD) may be used to help with the heart’s pumping action. This device is implanted in the patient’s abdomen and attached to the heart. These devices have proven to be beneficial to adults diagnosed with severe HF. The device may be used while the patient is awaiting transplant and, with continued research, may possibly eliminate the need for transplant in some patients (Figure 20-2).

• Heart transplant may be the only alternative for patients with advanced HF who do not respond to other medical or drug treatment. Heart transplant is discussed in Chapter 21.

• At least one herb is thought to be helpful for heart failure.

Short-term treatment for HF after an MI or open heart surgery is accomplished with the intraaortic balloon pump (IABP). The IABP is positioned in the descending aorta. The IABP is designed to increase blood supply to the myocardium and allow it to rest. The balloon will inflate during diastole, thus increasing perfusion to the coronary arteries. The balloon deflates during systole, making it easier for the left ventricle to eject blood (Figure 20-3).

Acute Pulmonary Edema

Acute pulmonary edema is a medical emergency that must be treated promptly. The patient with this condition has severe dyspnea; a cough productive of frothy, pink-tinged sputum; tachycardia; and moist, bubbling respirations with cyanosis. Nursing interventions for acute pulmonary edema include placing the patient in high Fowler’s position to relieve the dyspnea; administering oxygen, diuretics, morphine, and other prescribed drugs; limiting and monitoring activity; and assessing cardiopulmonary status.

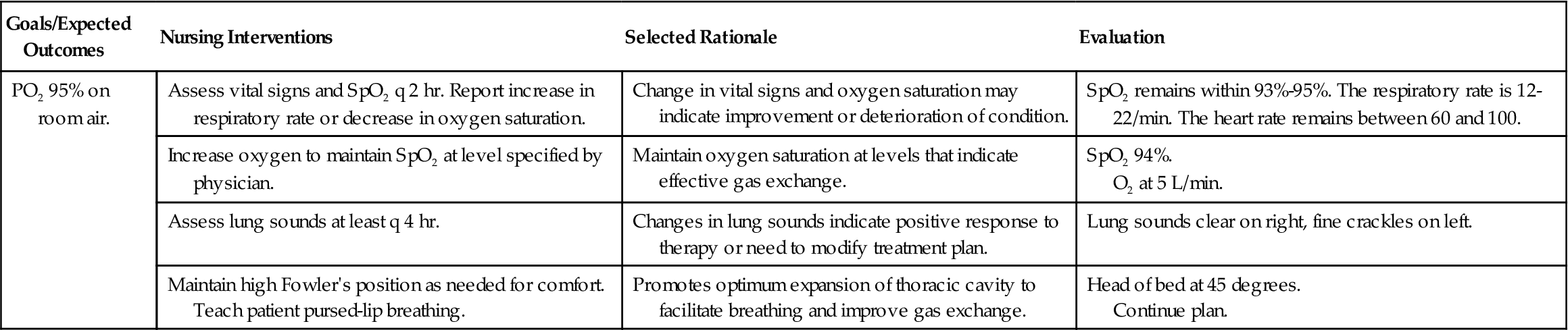

Nursing Management

Assessment (Data Collection)

The effects of HF can range from very mild to extremely serious. A thorough nursing assessment can help identify specific patient care problems. Data guide the physician in the evaluation of the patient’s response to medical treatment and the decision to continue or change prescribed drugs and other therapies. It is important to ask the patient if her clothes, rings, or shoes fit tighter than previously, indicating edema. Is pedal edema worsening or improving? Obtain an accurate weight. What has the trend of weight been? Feelings of breathlessness or having to catch the breath in midsentence may indicate fluid in the lungs and left-sided HF. Are crackles present in the lungs? Inquire how much activity causes SOB. Does the patient have paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (wakes up at night with SOB)? Ask about medication compliance and any problems or side effects noted. Assess the diet to determine usual sodium, fat, and calorie intake and obtain  a smoking history.

a smoking history.

Significant Findings Indicating Heart Failure is Occurring

Left-Sided Failure

Right-Sided Failure

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

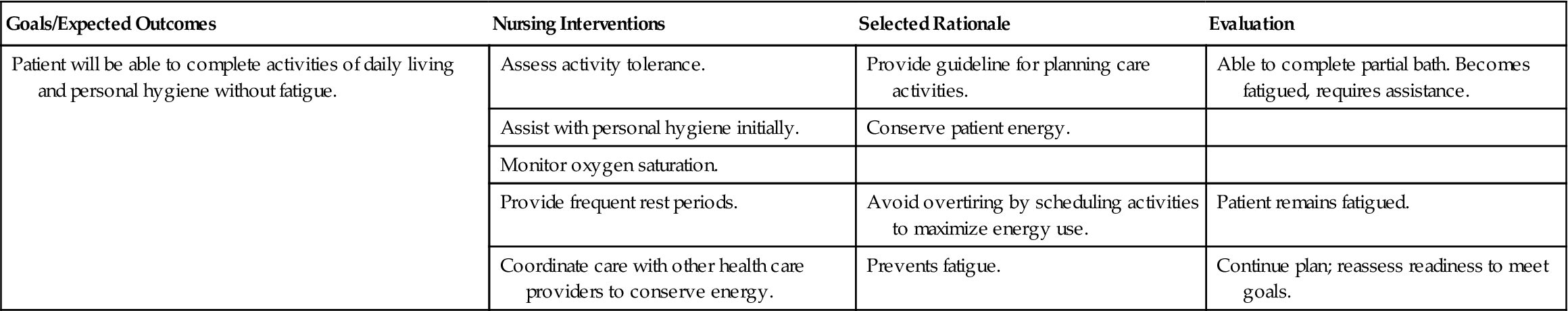

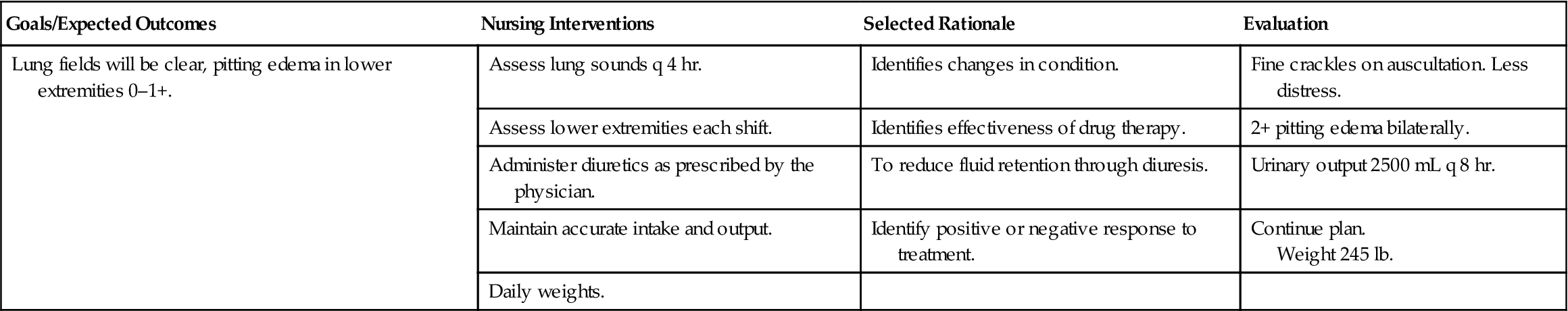

The main nursing diagnoses for the patient with HF are listed in Nursing Care Plan 20-1 (see also Table 18-4). Plan extra time when caring for the patient with HF because fatigue, possible lack of mobility, and oxygen deficit cause the patient to move slowly and need more time to accomplish the activities of daily living. Specific outcome criteria are written for each individual’s nursing diagnoses.

Nursing Care Plan 20-1

Nursing Care Plan 20-1

objective of Healthy People 2020 is to reduce hospitalizations of elderly adults with HF as the principal diagnosis. Thorough

objective of Healthy People 2020 is to reduce hospitalizations of elderly adults with HF as the principal diagnosis. Thorough