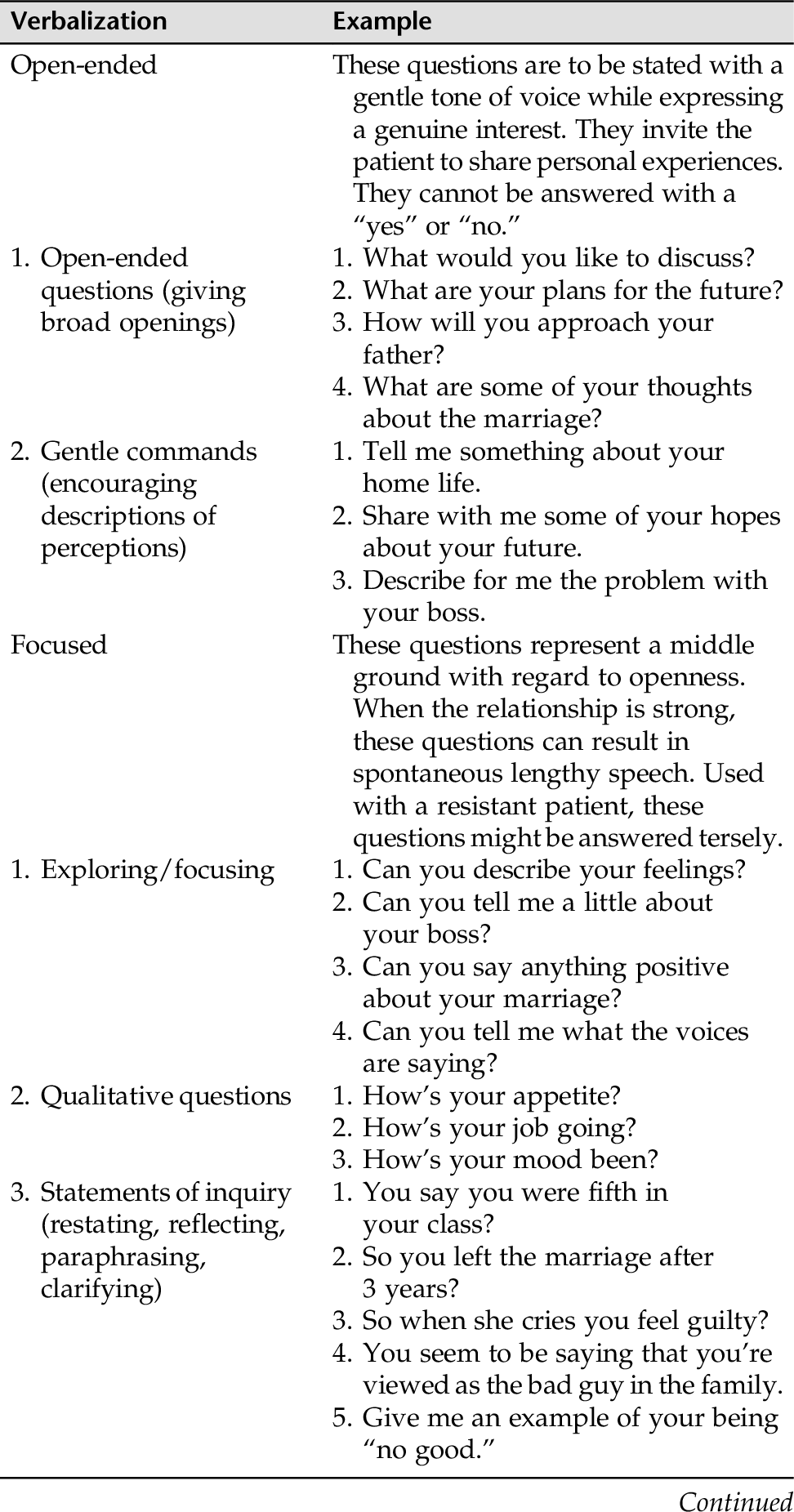

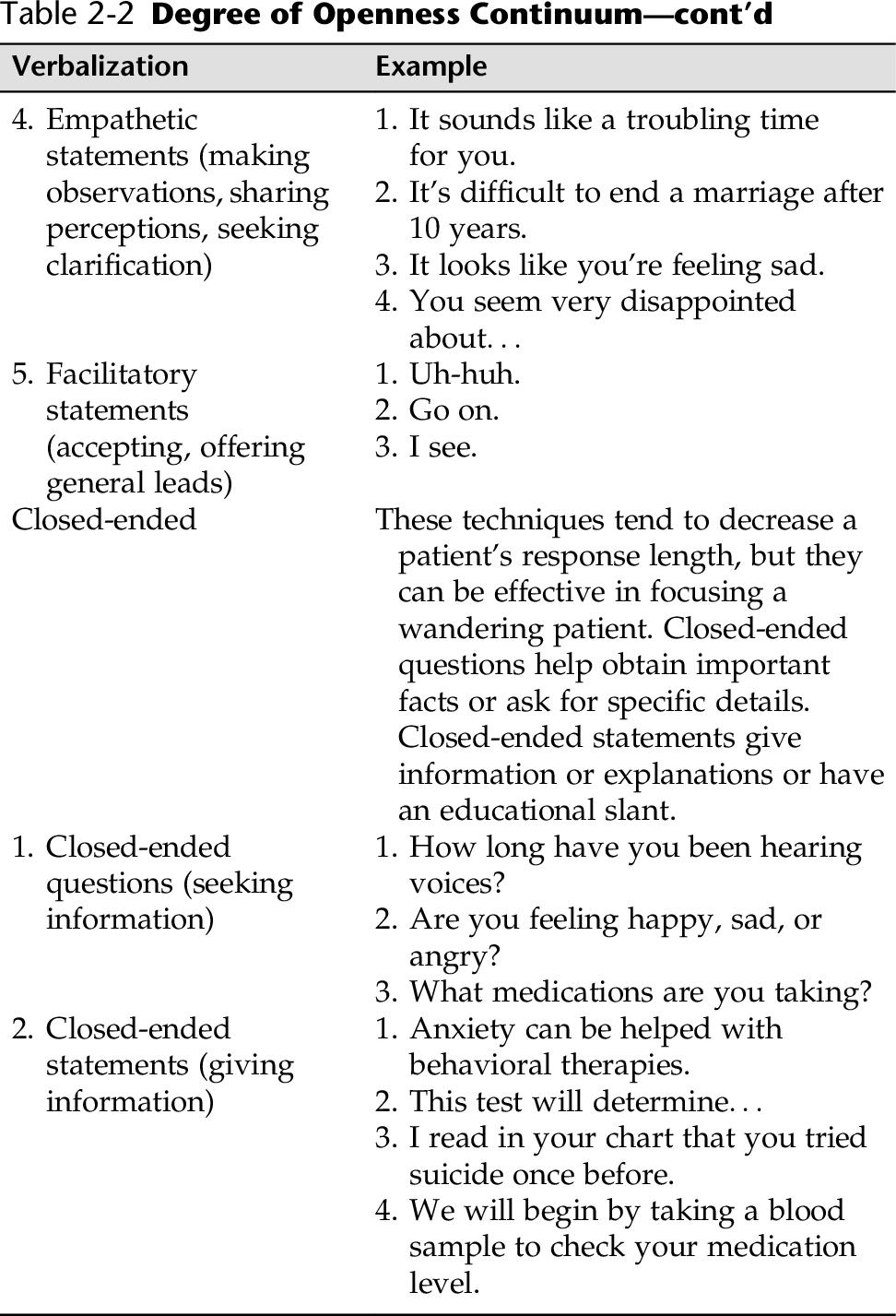

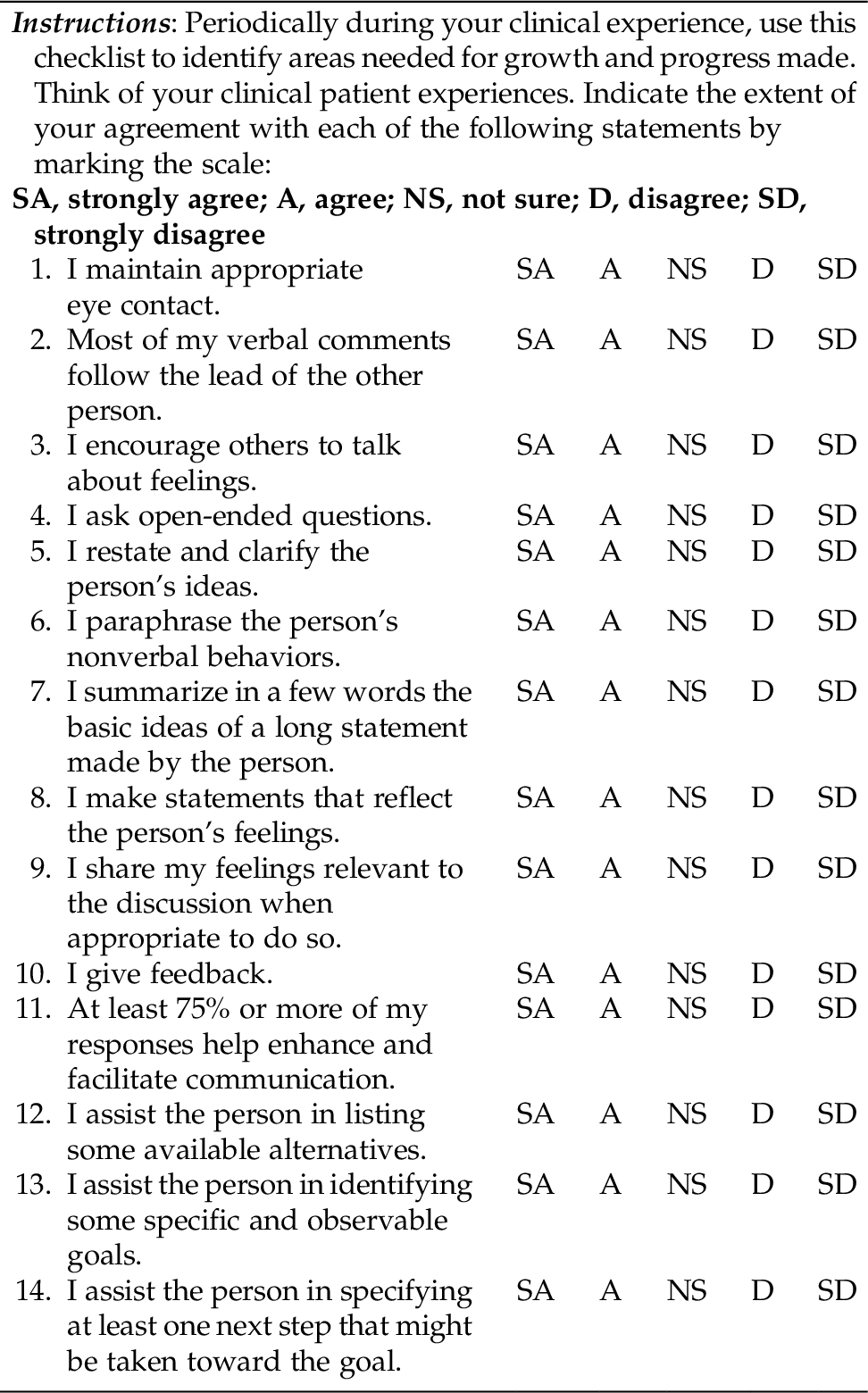

CHAPTER 2 Communication and interviewing techniques are acquired skills. Nurses learn to increase their ability to use communication and interviewing skills through practice and supervision. Communication is a complex process that can involve a variety of personal and environmental factors that might distort the sending and receiving of messages. Examples include: Personal factors: Emotions (mood), knowledge level, language use, attitudes, and bias Social factors: Previous experience, culture, language, and health beliefs and practice Environmental factors: Physical factors (background noise, lack of privacy, uncomfortable accommodations) and societal factors (presence of others, expectations of others) Communication is said to be 10% to 20% verbal and 80% to 90% nonverbal. Cultural and social factors influence concepts of what is health and what is illness, and practices vary greatly among cultures; thus it is important that mental health nurses learn a much broader understanding of the complexities of various cultures than are the norm today. Refer to Box 1-3 in Chapter 1 for a Brief Cultural and Social Questionnaire that may provide some questions to ask of the patient from a different cultural/social background. Verbal communication comprises all words a person speaks. Talking is our most common activity. Talking links us with others, it is our primary instrument of instruction, and it is one of the most personal aspects of our private life. When we speak, we do the following: • Communicate our beliefs, values, attitudes, and culture • Communicate perceptions and meanings • Convey interests and understanding or insult and convey judgment • Convey messages clearly or convey conflicting or implied messages • Convey clear, honest feelings or disguised, distorted feelings Verbal communication can become misunderstood and garbled even among people with the same primary language and/or the same cultural background. In our multiethnic society, keeping communication clear and congruent takes thought and insight. Communication styles, eye contact, and touch all have different meanings and are used and interpreted very differently among cultures. Ensuring that your verbal message is what you mean to convey, and that the message you send is the same message the other person receives, is a complicated skill. At times people convey conflicting messages. A person says one thing verbally, but conveys the opposite in nonverbal behavior. This is called a double message or mixed message. As in the saying, “actions speak louder than words,” actions are often interpreted as the true meaning of a person’s intent, whether that intent is conscious or unconscious. For example: A young man goes to counseling because he is not making good grades in school and fears that he will not be able to get into medical school. He appears bright and resourceful and states he has good study habits. In the course of the session, he tells the nurse that he is a star on the tennis team, is president of his fraternity, and has an active and successful social life, “If you know what I mean.” Implied in this exchange appears to be a double message. The verbal message is “I want good grades to get into medical school.” The nonverbal message is that what is important to him is spending a great deal of time excelling at a sport, heading a social club, and engaging in dating activities. One way nurses can respond to verbal and nonverbal incongruity (double messages) is to reflect and validate the individual’s thoughts and feelings. For example: “You say you are unhappy with your grades and as a consequence might not be able to get into medical school. Yet, from what I hear you say, you seem to be filling up your time excelling in so many other activities that there is very little time left for adequate preparation for excelling in your main goal, getting into medical school. I wonder what you think about this apparent contradiction in priorities.” Nonverbal communication consists of the behaviors displayed by an individual and as mentioned may account for 80% to 90% of the information being conveyed. Tone of voice and manner in which a person paces speech are examples of nonverbal communication. Other common examples of nonverbal communication (called cues) are facial expressions, body posture, amount of eye contact, eye cast (emotion expressed in the eyes), hand gestures, sighs, fidgeting, and yawning. Nonverbal communication consists of an amalgam of feelings, feedback, local wisdom, cultural rhythms, ways to avoid confrontation, and unconscious views of how the world works. Table 2-1 identifies some key components of nonverbal communication. Table 2-1 Nonverbal Behaviors Varcarolis, E. (2013). Communications. In M. J. Halter (Ed.), Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric mental health nursing (7th ed.). Philadelphia, Saunders, p. 150. Sometimes gestures and other nonverbal cues can have opposite meanings, depending on culture and context. For example, eye contact can be perceived as comforting and supportive or invasive and intimidating. Touching a patient gently on the arm can be experienced as supportive and caring or threatening or sexual. Facial expressions such as a smile can appear to convey warmth and interest or hide feelings of fear or anger. Many nonverbal cues have cultural meaning. In some Asian cultures, avoiding eye contact shows respect. Conversely, in many people with French, British, and African backgrounds, avoidance of eye contact by another person might be interpreted as disinterest, not telling the truth, avoiding the sharing of important information, or dictated by social order. There are numerous ways to interpret verbal and nonverbal communication for each cultural and subcultural group. Even if a nurse is aware of how a specific cultural group responds to, for example, touch, the nurse could still be in error when dealing with an individual within that cultural group. Sustaining effective and respectful communication is very complex. It is the task of nurses to identify and explore the meaning of patients’ nonverbal and verbal behaviors. Listed at the end of the chapter are Internet sites that provide further cultural information for health care professionals. Any question or statement can be classified as (1) an open-ended verbalization, (2) a focused question, or (3) a closed-ended verbalization. Furthermore, any question or statement can be classified along the continuum of openness. There are three variables that influence where any given verbalization sits on this openness continuum (Shea, 1998)*: 1. The degree to which the verbalization tends to produce spontaneous and lengthy response 2. The degree to which the verbalization does not limit the patient’s answer set 3. The degree to which the verbalization opens up a moderately resistant patient Refer to Table 2-2 during the following discussion. Open-ended questions require more than one-word answers (e.g., a “yes” or “no”). Even with a patient who is sullen, resistant, or guarded, open-ended questions can encourage lengthy information on experiences, perceptions of events, or responses to a situation. Examples of an open-ended question are: “What are some of the stresses you are grappling with?” “What do you perceive to be your biggest problem at the moment?” “Will you tell me something about your family?” Generally, nurses/clinicians applying the principles of therapeutic communication are encouraged to use open-ended questions or gentle inquiries (e.g., “Tell me about….”, “Share with me….”) with our patients. This is especially helpful when beginning a relationship and in the early interviews. Although the initial responses might be short, with time the responses often become more informative as the patient grows more at ease. This is an especially valuable technique to use with patients who are resistant or guarded, but it is also a good rule for opening phases of any interview, especially in the early phase of establishing a rapport with an individual. Closed-ended questions, in contrast, ask for specific information (e.g., dates, names, numbers, yes-or-no information). These are closed-ended questions because they limit the patient’s freedom of choice. Students are often discouraged from using closed-ended questions. When closed-ended questions are used frequently during a counseling session, or especially during an initial interview, they can close an interview down rapidly. This is especially true with a guarded or resistant patient. However, in some cases the answers to closed-ended questions are necessary and can provide important information. For example: “Do you feel like killing yourself now?” “How long have you been hearing the voices that tell you ‘bad things’?” “Did you seek therapy after your first suicide attempt?” “Do you think the medication is helping you?” Closed-ended questions give specific information when needed, such as during an initial assessment or intake interview or to ascertain results, as in “Are the medications helping you?” They are usually answered by a “yes,” a “no,” or a short answer. Useful tools for nurses in communicating with their patients are (1) clarifying/validating techniques, (2) the use of silence, and (3) active listening. Understanding depends on clear communication, which is aided by verifying with a patient the nurse’s interpretation of the patient’s messages. The nurse must request feedback on the accuracy of the message received from verbal and nonverbal cues. The use of clarifying techniques helps both participants to identify major differences in their frames of reference, giving them the opportunity to correct misperceptions before they cause any serious misunderstandings. The patient who is asked to elaborate on or clarify vague or ambiguous messages needs to know that the purpose is to promote mutual understanding. For example, “I hear you saying that you are having difficulty trusting your son after what happened. Is that correct?” For clarity, the nurse might use paraphrasing, which means to restate in different (often fewer) words the basic content of a patient’s message. Using simple, precise, and culturally relevant terms, the nurse can readily confirm interpretation of the patient’s previous message before the interview proceeds. By prefacing statements with a phrase such as “I am not sure I understand” or “In other words, you seem to be saying…,” the nurse helps the patient form a clearer perception of what might be a bewildering mass of details. After paraphrasing, the nurse must validate the accuracy of the restatement and its helpfulness to the discussion. The patient might confirm or deny the perceptions through nonverbal cues or by directly responding to a question such as “Was I correct in saying…?” As a result, the patient is made aware that the interviewer is actively involved in the search for understanding. With restating, the nurse mirrors the patient’s overt and covert messages; this technique can be used to echo feeling as well as content. Restating differs from paraphrasing in that it involves repetition of the same key words the patient has just spoken. If a patient remarks, “My life has been full of pain,” additional information might be gained by restating, “Your life has been full of pain.” The purpose of this technique is to more thoroughly explore subjects that might be significant. However, too frequent and indiscriminate use of restating might be interpreted by patients as inattention or disinterest. It is very easy to overuse this tool and become mechanical. Inappropriately parroting or mimicking what another has said might be perceived as ridiculing, making this nondirective approach a definite drawback to communication. To avoid overuse of restating, the nurse can combine restating with use of other clarifying techniques that encourage descriptions. For example: “Tell me about how your life has been full of pain.” “Give me an example of how your life has been full of pain.” Exploring is a technique that enables the nurse to more fully examine important ideas, experiences, or relationships. For example, if a patient states that he does not get along well with his wife, the nurse should explore this area further. Possible openers might include: “Tell me more about your relationship with your wife.” “Describe your relationship with your wife.” “Give me an example of you and your wife not getting along.” Asking for an example can greatly clarify a vague or generic statement made by a patient: Nurse: Give me an example of one person who doesn’t like you. Jim: Everything I do is wrong. Nurse: Give me an example of one thing you do that you think is wrong. In many cultures in our society, including nursing, there is an emphasis on action. In communication, we tend to expect a high level of verbal activity. Many students and practicing nurses find that when the flow of words stops, they become uncomfortable. The effective use of silence, however, is a helpful communication technique. Silence is not the absence of communication. Silence is a specific channel for transmitting and receiving messages. The practitioner needs to understand that silence is a significant means of influencing and being influenced by others. In the initial interview, the patient might be reluctant to speak because of the newness of the situation, the unfamiliarity with the nurse, self-consciousness, embarrassment, shyness, or anger. Talking is highly individualized. Some find the telephone a nuisance; others believe they cannot live without it. The nurse must recognize and respect individual differences in styles and tempos of responding. Although there is no universal rule about how much silence is too much, silence has been said to be worthwhile only when it is serving some function and not frightening the patient. Knowing when to speak during the interview is largely dependent on the nurse’s perception about what is being conveyed through the silence. Icy silence might be an expression of anger and hostility. Being ignored or “given the silent treatment” is recognized as an insult and is a particularly hurtful form of communication. For example, it has been observed that silence among some African-American patients might relate to anger, insulted feelings, or acknowledgment of a nurse’s lack of cultural sensitivity. Silence can also convey a person’s acceptance of another person; comfort in being with someone and sharing time together; that a person is pondering an idea or forming a response to what has just been said; or that a person is comfortable when there is nothing more to say at that moment. Successful interviewing might be dependent on the nurse’s “will to abstain”—that is, to refrain from talking more than necessary. Silence might provide meaningful moments of reflection for both participants. It gives each an opportunity to contemplate thoughtfully what has been said and felt, weigh alternatives, formulate new ideas, and gain a new perspective of the matter under discussion. If the nurse waits to speak and allows the patient to break the silence, the patient might share thoughts and feelings that could otherwise have been withheld. Nurses who feel compelled to fill every void with words often do so because of their own anxiety, self-consciousness, and embarrassment. When this occurs, the nurse’s need for comfort tends to take priority over the needs of the patient. Conversely, prolonged and frequent silences by the nurse can hinder an interview that requires verbal articulation. Although the nontalkative nurse might be comfortable with silence, this mode of communication might make the patient feel like a fountain of information to be drained dry. Moreover, without feedback, patients have no way of knowing whether what they said was understood. In naturally evolving interviews, open-ended techniques are interwoven with empathetic and facilitatory statements and closed-ended statements, all of which serve to clarify issues and demonstrate the interviewer’s interest (Shea, 1998). People want more than just physical presence in human communication. Most people are looking for the other person to be there for them psychologically, socially, and emotionally (Egan, 2009). Active listening includes: • Observing and paraphrasing the patient’s nonverbal behaviors • Listening to and seeking to understand patients in the context of the social setting of their lives • Listening for the “false notes” (e.g., inconsistencies or things the patient says that need more clarification) We have already noted that effective interviewers need to become accustomed to silence. It is just as important, however, for effective interviewers to learn to become active listeners when the patient is talking, as well as when the patient becomes silent. During active listening, we carefully note what the patient is saying verbally and nonverbally, and we monitor our own nonverbal responses. Using silence effectively and learning to listen on a deeper, more significant level to both the patient and our own thoughts and reactions are key ingredients in effective communication. Both these skills take time, profit from guidance, and can be learned. Here is a word of caution about listening. It is important for all of us to recognize that it is impossible to listen to people in an unbiased way. In the process of socialization, we develop cultural filters through which we listen to ourselves, others, and the world around us. The term cultural filters was coined by Egan (2009) to denote a form of cultural bias or cultural prejudice. One of the functions of culture is to provide a highly selective screen between us and the outside world. In its many forms, culture designates what we pay attention to and what we ignore. This screening provides structure for the world. We humans seem to need these cultural filters to provide structure for ourselves and help us interpret and interact with the world. But unavoidably, these cultural filters also introduce various forms of bias in our listening, because they are bound to influence our personal, professional, familial, and sociological values and interpretations. When nurses employ active listening techniques, they help strengthen a patient’s ability to solve personal problems. By giving the patient undivided attention, the nurse communicates that the patient is not alone; rather, the nurse is working along with the patient, seeking to understand and help. This kind of intervention enhances self-esteem and encourages the patient to direct energy toward finding ways to deal with problems. Serving as a sounding board, the nurse listens as the patient tests thoughts by voicing them aloud. This form of interpersonal interaction often enables the patient to clarify thinking, link ideas, and tentatively decide what should be done and how best to do it. Some techniques health care workers might employ are not useful and can negatively affect the interview and threaten rapport between the nurse and patient. Using ineffective techniques that set up barriers to communication is something we all have done and will do again. However, with thoughtful reflection and appropriate alternative therapeutic behaviors and methods, communication skills will become more effective, and confidence in interviewing abilities will be gained. Most importantly, the ability to work with patients will be improved—even those patients who present the greatest challenges. Supervision and peer support are immensely valuable in identifying techniques to target and change. Some of the most common approaches that can cause problems and are especially noticeable in the nurse who is new to psychosocial nursing are (1) asking excessive questions, (2) giving advice, (3) giving false reassurance, (4) requesting an explanation, and (5) giving approval. Excessive questioning, especially closed-ended questions, puts the nurse in the role of interrogator, demanding information without respect for the patient’s willingness or readiness to respond. This approach conveys lack of respect and sensitivity to the patient’s needs. Excessive questioning controls the range and nature of response and can easily result in a therapeutic stall or a shut-down interview. It is a controlling tactic and might reflect the interviewer’s lack of security in letting the patient tell his or her own story. It is better to ask more open-ended questions and follow the patient’s lead. For example: “Why did you leave your wife?” “Did you feel angry at her?” “What did she do to you?” “Are you going back to her?” Better to say: “Tell me about the situation between you and your wife.” When a nurse offers patients solutions, the inference could be that the nurse does not view the patient as capable of making effective decisions. Giving people advice can undermine their feelings of adequacy and competence. It can also foster dependence on the advice giver and shift problem-solving responsibility from the patient to the nurse. Giving constant advice to patients (or others for that matter) devalues the other individual and prevents the other person from working through and thinking through other options, either on their own or with the nurse. It keeps the “advice giver” in control and feeling like the strong one, although this might be unconscious on the nurse’s part. This is very different from giving information to people. People need information to make informed decisions. Patient: “I don’t know what to do about my brother. He is so lost.” Nurse: “You should call him up today and explain to him that you can’t support him any longer, and he will have to go on welfare.” (If I were you…Why don’t you…It would be best…) Better to say: Patient: “I don’t know what to do about my brother. He is so lost.” Nurse: “What do you see as some possible actions you can take?” (encourages problem solving) OR Patients often ask nurses for solutions. It is best to avoid this trap. Giving false reassurance underrates a person’s feelings and belittles a person’s concerns. This usually causes people to stop sharing feelings because they feel they are not taken seriously or are being ridiculed. As a result, the person’s real feelings remain undisclosed and unexplored. False reassurance in effect invalidates the patient’s experience and can lead to increased negative effect. “Don’t worry, things will get better.” “It’s not that bad.” “You’re doing just fine.” Better to say: “What specifically are you worried about?” “What do you think could go wrong?” “What do you see as the worst thing that could happen?” A “why” question from a person in authority (nurse, doctor, teacher) can be experienced as intrusive and judgmental. “Why” questions might put people on the defensive and serve to close down communication. It is much more useful to ask, “What is happening?” rather than why it is happening. People often have no idea why they did something, although almost everyone can make up a ready answer on the spot. Unfortunately, the answer is mostly defensive and not useful for further exploration. “Why don’t you leave him if he is so abusive?” “Why didn’t you take your medications?” “Why didn’t you keep your appointment?” Better to say: “What are the main reasons you stay in this relationship?” “Tell me about the difficulties you have regarding taking your medications.” “I notice you didn’t keep your appointment, even though you said that was a good time for you. What’s going on?” We often give our friends and family approval when we believe they have done something well. Even when what they have done is not that great, we make a big point of it. It is natural to bolster up friends’ and loved ones’ egos when they are feeling down. You might wonder what is wrong with giving a person a pat on the back once in a while. The answer is nothing, as long as it is done without involving a judgment (positive or negative) by the nurse. Giving approval in the nurse-patient relationship is a much more complex matter than giving approval or “a pat on the back” to a friend or colleague. People coming into the psychiatric setting are often feeling overwhelmed and alienated and might be down on themselves. During this time, patients are vulnerable and might be needy for recognition, approval, and attention. Yet, when people are feeling vulnerable, a value comment can be misinterpreted. For example: This message implies that the nurse was pleased by the way the patient kept his temper in a volatile situation. In many instances, the patient might see this as a way to please the nurse or get recognition from others. Therefore, the behavior becomes a way to gain approval. This can be a much healthier and more useful behavior for the patient, but when the motivation for any behavior starts to focus on getting recognition and approval from others, it stops coming from the individual’s own volition or conviction. When the people the patient wants approval from are not around, the motivation for the new behavior might not be there either, so it is not really a change in behavior as much as a ploy to win approval and acceptance from others. This response opens the door to finding out how the patient is feeling. Is this new behavior becoming easier? Was this situation of holding back anger difficult? Does the patient want to learn more assertiveness skills? Was it useful for the patient? Is there more about this situation the patient wants to discuss? The response by the nurse also makes it clear that this was a self-choice the patient made. The patient is given recognition for the change in behavior, and the topic is also open for further discussion. Gaining communication and counseling skills is a process that takes time. Self-assessment over time and noting areas of improvement and areas to target for the future might be helpful. Table 2-3 is a communication self-assessment checklist. It is helpful to check yourself frequently over time and note your progress.

Maximizing Communication Skills

VERBAL COMMUNICATION

NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION

Type

Possible Behaviors

Example

Body behavior

Posture, body movements, gestures, gait

Patient is slumped in a chair, puts her face in her hands, and occasionally taps her right foot.

Facial expressions

Frowns, smiles, grimaces; raised eyebrows, pursed lips, licking lips, tongue movements

Patient grimaces when speaking to the nurse; when alone, he smiles and giggles to himself.

Eye cast

Angry, suspicious, and accusatory looks

Patient’s eyes hardened with suspicion.

Voice-related behaviors

Tone, pitch, level, intensity, inflection, stuttering, pauses, silences, fluency

Patient talks in a loud, sing-song voice.

Observable autonomic physiological responses

Increase in respirations, diaphoresis, pupil dilation, blushing, paleness

When patient mentions discharge, she becomes pale, respirations increase, and her face becomes diaphoretic.

General appearance

Grooming, dress, hygiene

Patient is dressed in a wrinkled shirt, his pants are stained, his socks are dirty, and he wears no shoes.

Physical characteristics

Height, weight, physique, complexion

Patient appears grossly overweight for his height, and his muscle tone appears flabby.

EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION TECHNIQUES

Degree of Openness

Open-Ended Questions

Closed-Ended Questions

Clarifying/Validating Techniques

Paraphrasing

Restating

Exploring

Use of Silence

Active Listening

TECHNIQUES TO MONITOR AND AVOID

Asking Excessive Questions

Giving Advice

Giving False Reassurance

Requesting an Explanation: “Why” Questions

Giving Approval

ASSESSING YOUR COMMUNICATIONS SKILLS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree